“A Scorecard for Bank Performance: the Belgian Banking Industry.”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Third Supplemental Information Memorandum Dated 23 July 2019

Third Supplemental Information Memorandum dated 23 July 2019 LVMH FINANCE BELGIQUE SA (incorporated as société anonyme / naamloze vennootschap) under the laws of Belgium, with enterprise number 0897.212.188 RPR/RPM (Brussels)) EUR 4,000,000,000 Belgian Multi-currency Short-Term Treasury Notes Programme Irrevocably and unconditionally guaranteed by LVMH Moët Hennessy - Louis Vuitton SE (incorporated as European company under the laws of France, and registered under number 775 670 417 (R.C.S. Paris)) The Programme is rated A-1 by Standard & Poor’s Ratings Services, a division of the McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. and, Arranger Dealers Banque Fédérative du Crédit Mutuel BNP Paribas BRED Banque Populaire Crédit Agricole Corporate and Investment Bank Crédit Industriel et Commercial BNP Paribas Fortis SA/NV Natixis Société Générale ING Belgium SA/NV ING Bank N.V. Belgian Branch Issuing and Paying Agent BNP Paribas Fortis SA/NV This third supplemental information memorandum is dated 23 July 2019 (the “Third Supplemental Information Memorandum”) and is supplemental to, and shall be read in conjunction with, the information memorandum dated 20 October 2015 as supplemented on 21 April 2016 and on 28 April 2017 (the “Information Memorandum”). Unless otherwise defined herein, terms defined in the Information Memorandum have the same respective meanings when used in this Third Supplemental Information Memorandum. As of the date of this Third Supplemental Information Memorandum: (i) The Issuer herby makes the following additional disclosure: Moody's assigned on 3 July 2019 a first-time A1 long-term issuer rating and Prime-1 (P-1) short-term rating to LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton SE.; (ii) The paragraph 1.17 “Rating(s) of the Programme” of the section entitled “1. -

Frequently Asked Questions

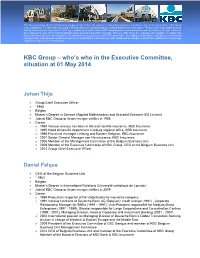

This document is provided for informational purposes only. It does not constitute a solicitation to buy/sell any product or security issued by the KBC Group or its subsidiaries. The information provided in this document is condensed and/or simplified and therefore incomplete. The document may contain forward- looking statements with respect to the strategy, earnings and capital trends of KBC, involving numerous assumptions and uncertainties. The risk exists that these statements may not be fulfilled and that future developments differ materially. Moreover, KBC does not undertake any obligation to update this document in line with new developments. The document may also contain non-IFRS information. By reading this document, each person is deemed to represent that he/she possesses sufficient expertise to understand the risks involved. KBC Group and its subsidiaries cannot be held liable for any damage resulting from the use of the information. KBC Group – who’s who in the Executive Committee, situation at 01 May 2014 Johan Thijs Group Chief Executive Officer °1965 Belgian Master’s Degree in Science (Applied Mathematics) and Actuarial Sciences (KU Leuven) Joined KBC Group or its pre-merger entities in 1988 Career o 1988 Various actuary functions in life and non-life insurance, ABB Insurance o 1995 Head of non-life department, Limburg regional office, ABB Insurance o 1998 Provincial manager Limburg and Eastern Belgium, KBC Insurance o 2001 Senior General Manager non-life insurance, KBC Insurance o 2006 Member of the Management Committee -

2021 VIB Belg BT Infomemo 04-08-2021.Pdf

Volkswagen International Belgium – Information Memorandum This Information Memorandum dated August 4, 2021 amends and replaces the information memorandum dated 18 October 2018 as supplemented from time to time. VOLKSWAGEN INTERNATIONAL BELGIUM SA (incorporated as naamloze vennootschap / société anonyme under the laws of Belgium, with enterprise number 443.615.642 (RPM/RPR Brussels)). EUR 5,000,000,000 Belgian Short-Term Treasury Notes Programme This Programme has been submitted to the STEP Secretariat in order to apply for the Short-Term European Paper (STEP- label). The status of STEP compliance of this Programme can be checked on the STEP Market website (www.stepmarket.org). The Programme is rated A-2 by Standard & Poor’s Ratings Services, a division of the McGraw-Hill Companies Inc. and P-2 by Moody’s Investors Service, Inc. Arranger Dealers BNP Paribas ING Bank N.V. Belgian Branch Crédit Agricole Corporate and Investment Bank Crédit Industriel et BNP Paribas Fortis SA/NV ING Belgium SA/NV Commercial BRED Banque Populaire KBC Bank NV Société Générale Issuing and Paying Agent – Domiciliary Agent BNP Paribas Fortis SA/NV Volkswagen International Belgium – Information Memorandum Potential investors are invited to read this Information Memorandum, the Conditions and the selling restrictions, prior to investing. Each holder of Treasury Notes from time to time represents through its acquisition of a Treasury Note that it is and, as long as it holds any Treasury Notes, shall remain an Eligible Holder. Nevertheless, a decision to invest in -

KBC Bank Half-Year Report

KBC Bank Half-Year Report - 1H2020 Interim Report – KBC Bank – 1H2020 p. 1 Company name ‘KBC’ or ‘KBC Bank’ as used in this report refer to the consolidated bank entity (i.e. KBC Bank NV including all companies that are included in the scope of consolidation). ‘KBC Bank NV’ refers solely to the non-consolidated entity. KBC Group or the KBC group refers to the parent company of KBC Bank (see below). Difference between KBC Bank and KBC Group KBC Bank is a subsidiary of KBC Group. Simplified, the KBC Group's legal structure has one single entity – KBC Group NV – in control of two underlying companies, viz. KBC Bank and KBC Insurance. Forward-looking statements The expectations, forecasts and statements regarding future developments that are contained in this report are, of course, based on assumptions and are contingent on a number of factors that will come into play in the future. Consequently, the actual situation may turn out to be (substantially) different. Glossary of ratios used (including the alternative performance measures) See separate section at the end of this report. Investor Relations contact details [email protected] www.kbc.com/kbcbank KBC Bank NV Investor Relations Office (IRO) Havenlaan 2 BE-1080 Brussels Belgium Management certification ‘I, Rik Scheerlinck, Chief Financial Officer of KBC Bank, certify on behalf of the Executive Committee of KBC Bank NV that, to the best of my knowledge, the abbreviated financial statements included in the interim report are based on the relevant accounting standards and fairly present in all material respects the financial condition and results of KBC Bank NV including its consolidated subsidiaries, and that the interim report provides a fair overview of the main events, the main transactions with related parties in the period under review and their impact on the abbreviated financial statements, and an overview of the main risks and uncertainties for the remainder of the current year.’ Interim Report – KBC Bank – 1H2020 p. -

Fitch Ratings ING Groep N.V. Ratings Report 2020-10-15

Banks Universal Commercial Banks Netherlands ING Groep N.V. Ratings Foreign Currency Long-Term IDR A+ Short-Term IDR F1 Derivative Counterparty Rating A+(dcr) Viability Rating a+ Key Rating Drivers Support Rating 5 Support Rating Floor NF Robust Company Profile, Solid Capitalisation: ING Groep N.V.’s ratings are supported by its leading franchise in retail and commercial banking in the Benelux region and adequate Sovereign Risk diversification in selected countries. The bank's resilient and diversified business model Long-Term Local- and Foreign- AAA emphasises lending operations with moderate exposure to volatile businesses, and it has a Currency IDRs sound record of earnings generation. The ratings also reflect the group's sound capital ratios Country Ceiling AAA and balanced funding profile. Outlooks Pandemic Stress: ING has enough rating headroom to absorb the deterioration in financial Long-Term Foreign-Currency Negative performance due to the economic fallout from the coronavirus crisis. The Negative Outlook IDR reflects the downside risks to Fitch’s baseline scenario, as pressure on the ratings would Sovereign Long-Term Local- and Negative increase substantially if the downturn is deeper or more prolonged than we currently expect. Foreign-Currency IDRs Asset Quality: The Stage 3 loan ratio remained sound at 2% at end-June 2020 despite the economic disruption generated by the lockdowns in the countries where ING operates. Fitch Applicable Criteria expects higher inflows of impaired loans from 4Q20 as the various support measures mature, driven by SMEs and mid-corporate borrowers and more vulnerable sectors such as oil and gas, Bank Rating Criteria (February 2020) shipping and transportation. -

Belgian Prime News Belgian

BELGIAN PRIME NEWS Quarterly publication Participating Primary and Recognised Dealers : Barclays, Belfius Bank, BNP Paribas Fortis, Citigroup, Crédit Agricole CIB, HSBC, KBC Bank, Morgan Stanley, Natixis, NatWest (RBS), Nomura, Société Générale Corporate & Investment Banking N° 88 June 2020 Last update : 25 June 2020 Next issue : September 2020 • MACROECONOMIC DEVELOPMENTS : Global economy faces incomplete and uncertain recovery following economic collapse • SPECIAL TOPIC : Belgian public finances are taking a serious hit from the COVID-19 pandemic • FINANCIAL MARKETS AND INTEREST RATES : Sovereign bonds yields remain low in an uncertain environment • TREASURY HIGHLIGHTS : 70 % of the (increased) financing target for 2020 already executed CONSENSUS Average of participants’ forecasts Belgium Euro area 2019 2020p 2021p 2019 2020p 2021p Real GDP (1) 1.4 -8.1 5.4 1.2 -8.3 5.8 Inflation (HICP) (1) 1.2 0.4 1.5 1.2 0.4 1.2 General government balance (2) –1.9 –8.6 –4.2 –0.6 –8.1 –2.8 Public debt (2) 98.7 115.6 112.2 86.0 100.5 98.0 (1) Percentage changes. (2) EDP definition ; percentages of GDP. SUCCESSIVE FORECASTS FOR BELGIUM eal rot HICP inflation 8 3 6 4 2 2 0 −2 −4 1 −6 −8 −10 0 III III IV III III IV IIIIII IV III III IV 2019 2020 2019 2020 For 2020 For 2021 Source : Belgian Prime News. www.nbb.be 1 MACROECONOMIC Global economy faces incomplete and uncertain DEVELOPMENTS recovery following economic collapse The first half of this year has brought major economic fall-out from the COVID-19 pandemic and the wide-ranging efforts and lockdown measures to contain its spread. -

High-Quality Service Is Key Differentiator for European Banks 2018 Greenwich Leaders: European Large Corporate Banking and Cash Management

High-Quality Service is Key Differentiator for European Banks 2018 Greenwich Leaders: European Large Corporate Banking and Cash Management Q1 2018 After weathering the chaos of the financial crisis and the subsequent restructuring of the European banking industry, Europe’s largest companies are enjoying a welcome phase of stability in their banking relationships. Credit is abundant (at least for big companies with good credit ratings), service is good and getting better, and banks are getting easier to work with. Aside from European corporates, the primary beneficiaries of this new stability are the big banks that already count many of Europe’s largest companies as clients. At the top of that list sits BNP Paribas, which is used for corporate banking by 65% of Europe’s largest companies. HSBC is next at 56%, followed by Deutsche Bank at 43%, UniCredit at 38% and Citi at 37%. These banks are the 2018 Greenwich Share Leaders℠ in European Top-Tier Large Corporate Banking. Greenwich Share Leaders — 2018 GREENWICH ASSOCIATES Greenwich Share20 1Leade8r European Top-Tier Large Corporate Banking Market Penetration Eurozone Top-Tier Large Corporate Banking Market Penetration Bank Market Penetration Statistical Rank Bank Market Penetration Statistical Rank BNP Paribas 1 BNP Paribas 1 HSBC 2 HSBC 2 Deutsche Bank 3 UniCredit 3T UniCredit 4T Deutsche Bank 3T Citi 4T Commerzbank 5T ING Bank 5T Note: Based on 576 respondents from top-tier companies. Note: Based on 360 respondents from top-tier companies. European Top-Tier Large Corporate Eurozone Top-Tier Large Corporate Cash Management Market Penetration Cash Management Market Penetration Bank Market Penetration Statistical Rank Bank Market Penetration Statistical Rank BNP Paribas ¡ 1 BNP Paribas 1 HSBC 2 HSBC 2T Deutsche Bank 3 UniCredit 2T Citi 4T Deutsche Bank 4 UniCredit 4T Commerzbank 5T ING Bank 5T Note: Based on 605 respondents from top-tier companies. -

18Th Annual M&A Advisor Awards Finalists I. Sector

18TH ANNUAL M&A ADVISOR AWARDS FINALISTS I. SECTOR DEAL OF THE YEAR ENERGY DEAL OF THE YEAR Acquisition of Oildex by DrillingInfo Vaquero Capital Intertek Restructuring of PetroQuest Energy FTI Consulting Heller, Draper, Patrick, Horn & Manthey, LLC. Houlihan Lokey Akin Gump Seaport Global Securities Porter Hedges LLP Dacarba Subordinated Preferred Equity Investment into Energy Distribution Partners Jordan, Knauff & Company Energy Distribution Partners Acquisition of Westinghouse Electric Company by Brookfield Business Partners Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman LLP Milbank, Tweed, Hadley & McCloy LLP Weil, Gotshal & Manges Willkie Farr & Gallagher LLP Recapitalization of kV Power by Rock Hill Capital Romanchuk & Co. Rock Hill Capital Atkins, Hollmann, Jones, Peacock, Lewis & Lyon, Inc. Restructuring of Jones Energy, Inc. Epiq Jackson Walker L.L.P Kirkland & Ellis Davis Polk & Wardwell LLP Merger of Transocean and Ocean Rig Seward & Kissel LLP King & Spalding LLP Transocean Ltd. Hamburger Ocean Rig UDW Inc. Maples and Calder Ogier Wenger & Vieli Ltd Acquisition of EQT Core Conventional Appalachia by Diversified Gas & Oil PLC Stifel RBC FINANCIALS DEAL OF THE YEAR Acquisition of First Team Resources Corporation by King Bancshares, Inc. GLC Advisors & Co. K Coe Isom Morris Laing King Bancshares, Inc. First Team Resources Corporation Stinson Merger of LourdMurray with Delphi Private Advisors, with an investment from HighTower Republic Capital Group HighTower LourdMurray Solomon Ward Seidenwurm & Smith, LLP Delphii Private Advisors 1 Acquisition of 1st Global Inc. by Blucora Inc. Haynes and Boone, LLP PJT Partners Foley & Lardner, LLP Blucora ERG Capital Merger of National Commerce Corporation with and into CenterState Bank Corporation Maynard Cooper & Gale P.C. Raymond James Nelson Mullins Riley & Scarbrough Keefe, Bruyette & Woods Inc. -

26 January 2018 Results of the Mandatory

26 JANUARY 2018 RESULTS OF THE MANDATORY PUBLIC TAKEOVER BID IN CASH AND SQUEEZE-OUT BY Natixis Belgique Investissements SA, a public limited company incorporated under Belgian law (the « Bidder ») ON ALL SHARES AND WARRANTS NOT YET OWNED BY THE BIDDER ISSUED BY Dalenys SA, a public limited company incorporated under Belgian law (the « Target Company »). Results of the bid The initial acceptance period of the mandatory takeover bid launched on 11 December 2017 by the Bidder on 8,620,827 shares representing 45,71% of the share capital and 38,67% of the voting rights of the Target Company and on 5,000 warrants (the “Bid”) ended on 22 January 2018. Following the initial acceptance period, the Bidder and the persons affiliated to him hold 18,401,437 shares and 3,432,944 profit shares representing 97,6 % of the share capital and 97,97 % of the voting rights in the Target Company. Payment of the bid price for the transferred shares will be made on 5 February 2018. Squeeze-out As the Bidder and the persons affiliated to him hold at least 95 % of the shares and securities with voting rights in the Target Company following the initial acceptance period, the Bidder decided to proceed with a squeeze out (in accordance with Article 513 of the Companies Code and Articles 42 and 43 in conjunction with Article 57 of the royal decree of 27 April 2007 on Takeover Bids) (the “Squeeze-out”) in order to acquire the shares and warrants issued by the Target Company not yet acquired by the Bidder, under the same terms and conditions as the Bid. -

United States District Court Southern District of New York

08-01789-smb Doc 16927 Filed 11/20/17 Entered 11/20/17 16:07:01 Main Document Pg 1 of 4 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK SECURITIES INVESTOR PROTECTION CORPORATION, No. 08-01789 (SMB) Plaintiff-Applicant, v. SIPA LIQUIDATION BERNARD L. MADOFF INVESTMENT SECURITIES LLC, Defendant. (Substantively Consolidated) In re: BERNARD L. MADOFF, Debtor. IRVING H. PICARD, Trustee for the Liquidation of Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities LLC, Plaintiff, v. Adv. Pro. Nos. listed on Exhibit 1 Attached Hereto DEFENDANTS LISTED ON EXHIBIT 1 ATTACHED HERETO, Defendants. DECLARATION OF REGINA GRIFFIN IN FURTHER SUPPORT OF THE TRUSTEE’S OMNIBUS MOTION FOR COURT ORDER AUTHORIZING LIMITED DISCOVERY PURSUANT TO FED. R. CIV. P. 26(d)(1) I, Regina Griffin, pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1746, declare as follows: 1. I am a member of the Bar of this Court and I am a partner with the law firm of Baker & Hostetler LLP, which is serving as counsel to Irving H. Picard, as trustee (the “Trustee”) for the substantively consolidated liquidation of Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities LLC (“BLMIS”) under the Securities Investor Protection Act, 15 U.S.C. § 78aaa et seq. (“SIPA”) and the estate of Bernard L. Madoff (“Madoff”). 2. As counsel to the Trustee, I have personal knowledge of the facts stated herein. 08-01789-smb Doc 16927 Filed 11/20/17 Entered 11/20/17 16:07:01 Main Document Pg 2 of 4 3. I make this declaration (“Declaration”) in further support of the Trustee’s Omnibus Motion for a Court Order Authorizing Limited Discovery Pursuant to Fed. -

Explanatory Note

Fortis SA/NV Explanatory note Explanatory note to the Agenda of the Ordinary and the Extraordinary General Meetings of Shareholders of Fortis SA/NV on 23 May 2007. Agenda item 2.2.: Dividend Agenda item 4: Appointments of members of the Board of Directors 2.2.1. Comments on the dividend policy Fortis aims to pay, on an annual basis, a dividend which is at 4.1.1. Reappointment of Mr Philippe Bodson least stable or growing, taking into account not only current The Board of Directors proposes the reappointment of baron profi tability and solvency but also the prospects of the Bodson for a period of three years, until the end of the general company. The dividend is paid in cash. An interim dividend is meeting of shareholders of 2010. paid in September. The interim dividend will in normal circumstances amount to 50% of the annual dividend over the Baron Bodson, a Belgian national, was born in 1944. preceding fi nancial year. This policy confi rms the importance that Fortis attaches to creating value for its shareholders. He joined Fortis as a member of the Board of Directors of Fortis in 2004. Baron Bodson is also Chairman of the Board of In accordance with the above policy, Fortis proposes a gross Directors of the Belgian listed company Exmar, Director of dividend of EUR 1.40 per Fortis Unit for 2006 against EUR Ashmore Energy (USA), Director of CIB, Chairman of 1.16 for 2005. Taking into account the interim dividend of EUR Floridienne, Member of CSFB Advisory Board Europe, 0.58 per Fortis Unit paid to the shareholders in September Director of Hermes Asset Management Europe Ltd. -

ADB's Trade Finance Program Confirming Banks List

Trade Finance Program Confirming Banks List As of 31 July 2016 AFGHANISTAN Bank Alfalah Limited (Afghanistan Branch) 410 Chahri-e-Sadarat Shar-e-Nou, Kabul, Afghanistan National Bank of Pakistan (Jalalabad Branch) Bank Street Near Haji Qadeer House Nahya Awal, Jalalabad, Afghanistan National Bank of Pakistan (Kabul Branch) House No. 2, Street No. 10 Wazir Akbar Khan, Kabul, Afghanistan ALGERIA HSBC Bank Middle East Limited, Algeria 10 Eme Etage El-Mohammadia 16212, Alger, Algeria ANGOLA Banco Millennium Angola SA Rua Rainha Ginga 83, Luanda, Angola ARGENTINA Banco Patagonia S.A. Av. De Mayo 701 24th floor C1084AAC, Buenos Aires, Argentina Banco Rio de la Plata S.A. Bartolome Mitre 480-8th Floor C1306AAH, Buenos Aires, Argentina AUSTRALIA Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited Level 20, 100 Queen Street, Melbourne, VIC 3000, Australia Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited (Adelaide Branch) Level 20, 11 Waymouth Street, Adelaide, Australia Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited (Adelaide Branch - Trade and Supply Chain) Level 20, 11 Waymouth Street, Adelaide, Australia Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited (Brisbane Branch) Level 18, 111 Eagle Street, Brisbane QLD 4000, Australia Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited (Brisbane Branch - Trade and Supply Chain) Level 18, 111 Eagle Street, Brisbane QLD 4000, Australia Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited (Perth Branch) Level 6, 77 St Georges Terrace, Perth, Australia Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited (Perth Branch - Trade