The Chopped Cheese: Traversing Upscale Foodways and the Struggle for Community Control

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Episode #019 British Food Part 4 - the (Earl Of) Sandwich

English Learning for Curious Minds | Episode #019 British Food Part 4 - The (Earl of) Sandwich Thank you - your ongoing membership makes Leonardo English possible. If you have questions we’d love to hear from you: [email protected] Episode #019 British Food Part 4 - The (Earl of) Sandwich January 21, 2020 [00:00:02] Hello, hello, hello, and welcome to the English Learning for Curious Minds podcast by Leonardo English. [00:00:09] I'm Alastair Budge and today it is part for the final part of our series on British food of our little sojourn1 into some weird British culinary history. [00:00:23] Before we get right into it, I want to remind those of you listening to this podcast on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, iVoox, or wherever you get your podcasts that you can grab a copy of the transcript and key vocabulary for the podcast on the website, which is Leonardoenglish.com. [00:00:42] The transcripts are super helpful if you want to follow along, and the key vocabulary means that you'll discover a whole load of new words and you won't have to stop to look things up in a dictionary. [00:00:54] The introductory promotional price for becoming a member of Leonardo English will end at midnight on January the 31st so if you want to lock in2 the 1 a temporary stay, e.g. "her sojourn in Rome". 2 to get and keep an advantage such as a low price © Leonardo English Limited www.leonardoenglish.com English Learning for Curious Minds | Episode #019 British Food Part 4 - The (Earl of) Sandwich introductory promotional price of just nine euros per month then make sure you become a member before then. -

Breakfastreakfast MATZO BALL SOUP: Bowl

Create Your Own Nosh Signature Sandwiches And a pickle for your health. SCHMEARS ADD ON’S Fresh Daily NYC’s Famous Ess-a-Bagels Fresh Daily REUBEN: (Hot pastrami, corned beef or turkey), russian dressing, swiss and sauerkraut pressed on seeded rye .....$20 Greater Knead Butter ....................$1 Plain Everything Pumpernickel RACHEL: (Hot pastrami, corned beef or turkey), russian dressing, swiss and coleslaw pressed on seeded rye ........$20 • • • Plain Cream Cheese ........$2 • Poppy • Whole Wheat • Bialy GF Bagels THE JERRY LEWIS: Triple decker of thinly sliced roast turkey, cole slaw, swiss cheese & russian dressing ........$16 Scallion Cream Cheese ......$3 • Salt • Whole Wheat $2 • GF Plain $3 Get a Vegetable .................$4 KELLERMAN’S FAVORITE: Pastrami, corned beef and turkey w/ russian dressing and coleslaw on seeded rye .$16 • Sesame Everything • GF Everything ozen • Onion • Cinnamon Raisin Baker’s D Horseradish ...............$4 THE MRS. MAISEL: Pastrami, schmear of chopped liver, red onion, and deli mustard on rye bread .............$16 $24 13 bagels Jalapeño .................$4 THE HENNY YOUNGMAN: Hot corned beef on top of a potato knish, served open-faced with melted swiss .$16 Sichuan Chili Crisp .........$4 THE JOAN RIVERS: Pastrami, schmear of chopped liver, tomato and russian dressing ...................... $16 Seasonal Berry .............$4 $2 FRESH BAKED BREADS THE BUNGALOW CLUB: Triple decker, turkey, bacon, & swiss on rye toast w/ lettuce, tomato, onion and mayo .$16 Tofu Cream Cheese .........$4 • Rye (Seeded or Unseeded) • Multi-Grain • Challah Roll Tofu Scallion Cream Cheese ..$5 Lox Cream Cheese ..........$5 And a pickle for your health. Sandwich Classics SMOKED FISH ADD ON’S SALAD ADD ON’S ADD ONS BY C H E F N I C K LIB E R A T O • Hot Pastrami on rye with deli mustard ......$20 • Fresh Roasted Turkey (Choice of bread) .....$15 Eastern Gaspe Nova .........$8 Egg ......................$6 Lettuce ............. -

Appetizers and Small Plates Personal Deep-Dish Pizzas Sliders Burgers

Appetizers and Small Plates Fried Pickles 9 Pretzel Rods 10 Chipotle Dipping Sauce Tillamook Cheddar Sauce Or Maple Cinnamon Butter Roasted Tomato & Garlic Cheesesticks 11 Latin Jumbo Shrimp Cocktail 14 Mozzerella, Provolone, White Cheddar, Muenster, Parmesan, Cumin Poached Shrimp, Cocktail, Citrus Aioli Roasted Tomatoes, Roasted Garlic Cloves, Ammoglio Sauce Buffalo Cauliflower 10 Greek Chicken Skewers 13 Roasted Cauliflower Tossed In Buffalo, Carrots, Celery Cucumber, Tomato, Olives, Feta, Balsamic Glaze Ranch or Blue Cheese Dressing Cajun Steak Bites 14 Maple Bourbon Brussel Sprouts 12 Blackened Tenderloin Tips, Potatoes, Caramelized Onions, Demi- Roasted Sprouts, Caramelized Onion, Cranberries, Toasted Pepitas, Glace, Grilled Bread Feta Cheese, Maple Bourbon Balsamic Glaze Add Blue Cheese $2 Smoked Salmon Cheesecake 13 Nacho Supreme 13 Cracker Crust, Fried Capers, Tomato, Crostini, Preserved White Corn Tortilla Chips, Chili Con Queso, Shredded Lettuce, Lemon Pico de Gallo, Black Olives, Guacamole, Salsa, and Sour Cream. Choice of Beef, Chicken, or Smoked Pulled Pork. Buffalo Wings 13 Guacamole Dip 9 10 Lightly Smoked, Fried Wings Or ½ Lb. Of Boneless. Tossed In 5- Housemade Guacamole, White Corn Tortilla Chips Alarm Habanero, Hot, Buffalo, BBQ, Honey BBQ, Parmesan Garlic, Add Chili Con Queso 2 Add Salsa 2 Cajun Rub, Mesquite Rub, Lemon Pepper, Or Plain. Carrot Sticks, Celery Sticks, Blue Cheese or Ranch Quesadilla 14 Buttermilk Fried Chicken Strips 12 Grilled Chicken, Smoked Pulled Pork, Or Grilled Veggie. Cheddar, House Cut Fries -

Annual Garden Tea Amended Agenda

TONIGHT Mostly Clear. Low of 64. Search for The Westfield News The WestfieldNews Search for The Westfield News “THE MAIN DANGERS Westfield350.com The Westfield News IN THIS LIFE ARE THE Serving Westfield, Southwick, and surrounding Hilltowns “TIMEPEOPLE IS THE WHOONLY WANT WEATHER TO CHANGECRITIC WITHOUT EVERY THING TONIGHT —AMBITION OR NO.”THING .” Partly Cloudy. — ViscountessJOHN STEINBECK NANCY ASTOR Search for The Westfield News Westfield350.comWestfield350.orgLow of 55. Thewww.thewestfieldnews.com WestfieldNews Serving Westfield, Southwick, and surrounding Hilltowns “TIME IS THE ONLY WEATHERVOL. 86 NO. 151 TUESDAY, JUNE 27, 2017 75CRITIC centsWITHOUT VOL. 88 NO. 151 THURSDAY, JUNE 27, 2019 75 Cents TONIGHT AMBITION.” Partly Cloudy. JOHN STEINBECK Low of 55. www.thewestfieldnews.com Southwick VOL.Rotary 86 NO. 151Summer TUESDAY, JUNE 27, 2017 Thursday’s 75 cents Concert Series budget review kicks-off in July By HOPE E. TREMBLAY and vote on Correspondent SOUTHWICK – It’s officially summer and Southwick Rotary final passage Club is heating up the town with its third annual concert series. The first of three scheduled Southwick Rotary concerts fea- still on tures funk rhythm performer Rich By AMY PORTER Sadowski and the Blues Band July Correspondent 17. WESTFIELD – The Special City Council meet- “He is a very talented performer ing to finalize the FY20 budget is still on for who plays all over, including in Thursday, June 27 in Council Chambers with an Europe,” said Rotarian Robert Annual Garden Tea amended agenda. The first item reads Budget Fox. The Rocks laugh with Mary O’Connell and Michelle Moriarty at the Westfield Workshop/Committee of the Whole to review the The series takes place at Whalley Woman’s Club 22nd Annual Garden Tea fundraiser Wed., June 26 at Stanley Park. -

The Parkview Pantera

TThehe ParkviewParkview Pantera DECEMBER 2016 NEWS AROUND PHS Volume XLL, Edition I I Toys for Tots gives back to the community that the club accumulates in monetary donations is used to purchase additional toys, which are also sent to the warehouse for distribution. This year on all week- NEWS (2-3) ends through December 17th, JROTC students will be collecting donations in front of several, local Wal- Mart and Kroger stores, according to cadet private Annaliese Mayo, “Some- times, parents can’t afford to buy toys for their kids, and we’re trying to help those FEATURES (5-8) parents out so their kids can have toys too.” Parkview students can also contribute to the cause by donating to the Toys for Tots donation box in the front offi ce. Not everyone can enjoy the festivity of the holidays, Cadet Gunnery Sergeant Samantha Green (left) and Cadet Private Anna Mayo (right) do- and in recognition of such, nate their time to Toys for Tots during the holiday season. (Photo courtesy of Jolie Mayo) JROTC students are working OPINION (9-14) especially hard to ease the By Jenny Nguyen, Copy JROTC helps out in the op- donations through local strain for others who are less Editor erations of the U.S. Marine retail and grocery stores, has fortunate. “[The program] Corps Toys for Tots Pro- successfully expanded their impacts people, and I tell it The Christmas season gram, which serves to collect annual contributions to over to the students all the time. has offi cially come into its and deliver Christmas gifts $70,000. -

Pisco Y Nazca Doral Lunch Menu

... ... ··············································································· ·:··.. .·•. ..... .. ···· : . ·.·. P I S C O v N A Z C A · ..· CEVICHE GASTROBAR miami spice ° 28 LUNCH FIRST select 1 CAUSA CROCANTE panko shrimp, whipped potato, rocoto aioli CEVICHE CREMOSO fsh, shrimp, creamy leche de tigre, sweet potato, ají limo TOSTONES pulled pork, avocado, salsa criolla, ají amarillo mojo PAPAS A LA HUANCAINA Idaho potatoes, huancaina sauce, boiled egg, botija olives served cold EMPANADAS DE AJí de gallina chicken stew, rocoto pepper aioli, ají amarillo SECOND select 1 ANTICUCHO DE POLLO platter grilled chicken skewers, anticuchera sauce, arroz con choclo, side salad POLLO SALTADO wok-seared chicken, soy and oyster sauce, onions, tomato wedges, arroz con choclo, fries RESACA burger 8 oz. ground beef, rocoto aioli, queso fresco, sweet plantains, ají panca jam, shoestring potatoes, served on a Kaiser roll add fried egg 1.5 TALLARín SALTADO chicken stir-fry, soy and oyster sauce, onions, tomato, ginger, linguini CHICHARRÓN DE PESCADO fried fsh, spicy Asian sauce, arroz chaufa blanco CHAUFA DE MARISCOS shrimp, calamari, chifa fried rice DESSERTS select 1 FLAN ‘crema volteada’ Peruvian style fan, grilled pineapple, quinoa tuile Alfajores 6 Traditional Peruvian cookies flled with dulce de leche SUSPIRO .. dulce de leche custard, meringue, passion fruit glaze . .. .. .. ~ . ·.... ..... ................................................................................. traditional inspired dishes ' spicy ..... .. ... Items subject to -

PRAGUE ““Inin Youryour Pocket:Pocket: a Cheeky,Cheeky, Wwell-Ell- Wwrittenritten Sserieseries Ooff Gguidebooks.”Uidebooks.” Tthehe Nnewew Yyorkork Timestimes

Hotels Restaurants Cafés Nightlife Sightseeing Events Maps PRAGUE ““InIn YYourour Pocket:Pocket: A cheeky,cheeky, wwell-ell- wwrittenritten sserieseries ooff gguidebooks.”uidebooks.” TThehe NNewew YYorkork TimesTimes OOctoberctober - NNovemberovember 22009009 Velvet Revolution The 20th anniversary Czech Spas Relaxing all over the country N°53 - 100 Kč www.inyourpocket.com Hotel Absolutum boutique hotel in Prague Hotel Absolutum is pleased to announce that pop and disco band BONEY M. was a VIP guest. For more information see www.absolutumhotel.cz BONEY M. Jablonského 639/4, 170 00 Praha 7 T:+420 222 541 406, F:+420 222 541 407 Email: [email protected] www.absolutumhotel.cz CONTENTS 5 ESSENTIAL CITY GUIDES www.inyourpocket.com Contents Arrival & Getting Around 8 Culture & Events 10 Theatre, Festivals Velvet Revolution 15 Hotels - Where to stay 16 Whatever your budget or needs Restaurants 24 Guláš to gourmet and everything in between Cafés 40 Historical slices of Czech life with cake Czech Spas 42 Relaxing all over the country Georg Baselitz Through 6 December Nightlife 54 Explore the depths of Prague’s bars and clubs Sightseeing Essential sights 64 The castle, the bridge, the clock Directory Shopping 74 Business 75 Lifestyle 76 Adult entertaiment 81 Maps & Index Street index 86 City centre map 87 City map 88-89 Index 90 © Ursula Schulz prague.inyourpocket.com October - November 2009 6 FOREWORD Autumn is a difficult time for the Prague In Your Pocket office. We are melancholy about the summer’s end; but Europe In Your Pocket in a way looking forward to brisk days and colourful trees. Luckily the excitement and action that is Prague comes the place to be into full play these months, giving our minds something else to dwell on besides the passing of long summer evenings. -

With No Catchy Taglines Or Slogans, Showtime Has Muscled Its Way Into the Premium-Cable Elite

With no catchy taglines or slogans, Showtime has muscled its way into the premium-cable elite. “A brand needs to be much deeper than a slogan,” chairman David Nevins says. “It needs to be a marker of quality.” BY GRAHAM FLASHNER ixteen floors above the Wilshire corridor in entertainment. In comedy, they have a sub-brand of doing interesting things West Los Angeles, Showtime chairman and with damaged or self-destructive characters.” CEO David Nevins sits in a plush corner office Showtime can skew male (Ray Donovan, House of Lies) and female (The lined with mementos, including a prop knife Chi, SMILF). It’s dabbled in thrillers (Homeland), black comedies (Shameless), from the Dexter finale and ringside tickets to adult dramas (The Affair), docu-series (The Circus) and animation (Our the Pacquiao-Mayweather fight, which Showtime Cartoon President). It’s taken viewers on journeys into worlds TV rarely presented on PPV. “People look to us to be adventurous,” he explores, from hedge funds (Billions) to management consulting (House of says. “They look to us for the next new thing. Everything we Lies) and drug addiction (Patrick Melrose). make better be pushing the limits of the medium forward.” Fox 21 president Bert Salke calls Showtime “the thinking man’s network,” Every business has its longstanding rivalries. Coke and Pepsi. Marvel and noting, “They make smart television. HBO tries to be more things to more DC. For its first thirty-odd years, Showtime Networks (now owned by CBS people: comedy specials, more half-hours. Showtime is a bit more interested Corporation) ran a distant second to HBO. -

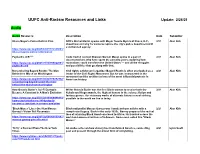

UUFC Anti-Racism Resources and Links Update: 2/28/21

UUFC Anti-Racism Resources and Links Update: 2/28/21 Audio Audio Resource Description Date Submitter Ithaca Mayor's Police Reform Plan NPR's Michel Martin speaks with Mayor Svante Myrick of Ithaca, N.Y., 2/21 Alan Kirk about how and why he wants to replace the city's police department with a civilian-led agency. https://www.npr.org/2021/02/27/972145001/ ithaca-mayors-police-reform-plan Payback's A B**** Code Switch co-host Shereen Marisol Meraji spoke to a pair of 2/21 Alan Kirk documentarians who have spent the past two years exploring how https://www.npr.org/2021/01/14/956822681/ reparations could transform the United States — and all the struggles paybacks-a-b and possibilities that go along with that. Remembering Bayard Rustin: The Man Civil rights activist and organizer Bayard Rustin is often overlooked as a 2/21 Alan Kirk Behind the March on Washington leader of the Civil Rights Movement. But he was instrumental in the movement and the architect of one of the most influential protests in https://www.npr.org/2021/02/22/970292302/ American history. remembering-bayard-rustin-the-man- behind-the-march-on-washington How Octavia Butler's Sci-Fi Dystopia Writer Octavia Butler was the first Black woman to receive both the 2/21 Alan Kirk Became A Constant In A Man's Evolution Nebula and Hugo awards, the highest honors in the science fiction and fantasy genres. Her visionary works of alternate futures reveal striking https://www.npr.org/2021/02/16/968498810/ parallels to the world we live in today. -

Makeup-Hairstyling-2019-V1-Ballot.Pdf

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Hairstyling For A Single-Camera Series A.P. Bio Melvin April 11, 2019 Synopsis Jack's war with his neighbor reaches a turning point when it threatens to ruin a date with Lynette. And when the school photographer ups his rate, Durbin takes school pictures into his own hands. Technical Description Lynette’s hair was flat-ironed straight and styled. Glenn’s hair was blow-dried and styled with pomade. Lyric’s wigs are flat-ironed straight or curled with a marcel iron; a Marie Antoinette wig was created using a ¾” marcel iron and white-color spray. Jean and Paula’s (Paula = set in pin curls) curls were created with a ¾” marcel iron and Redken Hot Sets. Aparna’s hair is blow-dried straight and ends flipped up with a metal round brush. Nancy Martinez, Department Head Hairstylist Kristine Tack, Key Hairstylist American Gods Donar The Great April 14, 2019 Synopsis Shadow and Mr. Wednesday seek out Dvalin to repair the Gungnir spear. But before the dwarf is able to etch the runes of war, he requires a powerful artifact in exchange. On the journey, Wednesday tells Shadow the story of Donar the Great, set in a 1930’s Burlesque Cabaret flashback. Technical Description Mr. Weds slicked for Cabaret and two 1930-40’s inspired styles. Mr. Nancy was finger-waved. Donar wore long and medium lace wigs and a short haircut for time cuts. Columbia wore a lace wig ironed and pin curled for movement. TechBoy wore short lace wig. Showgirls wore wigs and wig caps backstage audience men in feminine styles women in masculine styles. -

Breakfast Buffets

Breakfast Buffets Continental european breakfast breakfast Fresh Baked Muffins Fruit Salad Danishes Infused Yogurts New York Style Bagels Fresh Baked Muffins Assorted Cream Cheese Danishes Whipped Butter New York Style Bagels Assorted Cream Cheese Whipped Butter sunrise hot breakfast breakfast Sliced Seasonal Fruit Gently Scrambled Local Eggs Assorted Cereals with Whole & Skim Milk Applewood Smoked Bacon Fresh Baked Muffins Country Style Sausage Links or Patties Danishes Breakfast Potatoes New York Style Bagels Buttermilk Biscuits Assorted Cream Cheeses Whipped Butter The breakfast Sliced Seasonal Fruit Individual Boxed Cereals with Whole & Skim Milk Assortment of Breakfast Pastries, Croissants, & Freshly Baked Fruit Preserves & Whipped Sweet Cream Butter Gently Scrambled Local Eggs with Chives Applewood Smoked Bacon & Savory Sausage Links Breakfast Potatoes Breakfast Buffets l a t i n breakfast Sliced Seasonal Fruit Assorted Breakfast Pastries, Croissants, & Freshly Baked Muffins Fruit Preserves & Whipped Sweet Cream Butter Arepas de Queso, Corn Cakes, Cheese, & Whipped Butter Chilaquiles Scrambled Eggs, Crispy Tortillas, Smoked Pulled Chicken, Salsa Verde, & Sour Cream Chorizo con Papas: Spicy Mexican Chorizo, Breakfast Potatoes, & Cilantro Applewood Smoked Bacon & Savory Sausage Links bluegrass chilaquiles breakfast Sliced Seasonal Fruit Buttermilk Biscuits & Sausage Gravy Hot Brown Inspired Hash with Bacon, Cheddar, & Smoked Turkey Gently Scrambled Local Eggs with Red Pepper & Green Onion breakfast burritos Choice of: Applewood Smoked -

Boneless Chicken Wings Traditional Chicken Wings

Boneless Chicken Wings Single Order $10 Double Order $14 Fresh and hand cut Traditional Chicken Wings 5 for $6, 10 for $11, 20 for $20 Mild, Medium, Hot, Extra Hot, Traditional BBQ, Garlic Parmesan, Stoner Wings (BBQ and Medium sauces mixed), Flavor of the Week Premium Sauces are an additional fifty cents: Cajun, Sweet Chili, 24Karat, Bang Bang, Asian, Honey BBQ Onion Rings Tuscan Spinach Dip Crispy breaded golden brown onion rings. Homemade cheese dip, mixed with roasted peppers, Deep fried and served with our horseradish garlic, spinach, artichoke hearts. dipping sauce. $7 Topped with melted cheddar and Monterey cheese. Mozzarella Sticks Served with tortilla chips. $10 Served with your choice of raspberry melba or marinara sauce. $8 Nachos Grande Tortilla chips piled high with your choice of Bavarian Pretzel Sticks beef or chicken. Served with a side of our homemade queso sauce. Topped with shredded lettuce, diced tomatoes, melted $9 cheese, black olives, and scallions. Served with sides of salsa and sour cream. Bentley’s Quesadillas $7 / $11 A grilled tortilla shell filled with a blend of cheese, Add Jalapeños $1 scallions, and tomatoes. Add a side of Queso or Guacamole $2 Served with salsa and sour cream. $8 Add Chicken $3 Add Steak $4 Tavern Fries French fries topped with melted cheddar and Harvest Quesadillas Monterey cheese. Finished with crumbled bacon and a side of ranch Grilled sundried tomato tortilla filled with dressing. $7 / $11 grilled chicken, cheese, scallions, tomatoes and pesto sauce. Chicken Tenders Served with salsa and sour cream. $11 Chicken tenders served with a side of BBQ sauce.