Bees. the Tools of Their Trade

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evolution of the Suctorial Proboscis in Pollen Wasps (Masarinae, Vespidae)

Arthropod Structure & Development 31 (2002) 103–120 www.elsevier.com/locate/asd Evolution of the suctorial proboscis in pollen wasps (Masarinae, Vespidae) Harald W. Krenna,*, Volker Maussb, John Planta aInstitut fu¨r Zoologie, Universita¨t Wien, Althanstraße 14, A-1090, Vienna, Austria bStaatliches Museum fu¨r Naturkunde, Abt. Entomologie, Rosenstein 1, D-70191 Stuttgart, Germany Received 7 May 2002; accepted 17 July 2002 Abstract The morphology and functional anatomy of the mouthparts of pollen wasps (Masarinae, Hymenoptera) are examined by dissection, light microscopy and scanning electron microscopy, supplemented by field observations of flower visiting behavior. This paper focuses on the evolution of the long suctorial proboscis in pollen wasps, which is formed by the glossa, in context with nectar feeding from narrow and deep corolla of flowers. Morphological innovations are described for flower visiting insects, in particular for Masarinae, that are crucial for the production of a long proboscis such as the formation of a closed, air-tight food tube, specializations in the apical intake region, modification of the basal articulation of the glossa, and novel means of retraction, extension and storage of the elongated parts. A cladistic analysis provides a framework to reconstruct the general pathways of proboscis evolution in pollen wasps. The elongation of the proboscis in context with nectar and pollen feeding is discussed for aculeate Hymenoptera. q 2002 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved. Keywords: Mouthparts; Flower visiting; Functional anatomy; Morphological innovation; Evolution; Cladistics; Hymenoptera 1. Introduction Some have very long proboscides; however, in contrast to bees, the proboscis is formed only by the glossa and, in Evolution of elongate suctorial mouthparts have some species, it is looped back into the prementum when in occurred separately in several lineages of Hymenoptera in repose (Bradley, 1922; Schremmer, 1961; Richards, 1962; association with uptake of floral nectar. -

Chapter 02 Biogeography and Evolution in the Tropics

Chapter 02 Biogeography and Evolution in the Tropics (a) (b) PLATE 2-1 (a) Coquerel’s Sifaka (Propithecus coquereli), a lemur species common to low-elevation, dry deciduous forests in Madagascar. (b) Ring-tailed lemurs (Lemur catta) are highly social. PowerPoint Tips (Refer to the Microsoft Help feature for specific questions about PowerPoint. Copyright The Princeton University Press. Permission required for reproduction or display. FIGURE 2-1 This map shows the major biogeographic regions of the world. Each is distinct from the others because each has various endemic groups of plants and animals. FIGURE 2-2 Wallace’s Line was originally developed by Alfred Russel Wallace based on the distribution of animal groups. Those typical of tropical Asia occur on the west side of the line; those typical of Australia and New Guinea occur on the east side of the line. FIGURE 2-3 Examples of animals found on either side of Wallace’s Line. West of the line, nearer tropical Asia, one 3 nds species such as (a) proboscis monkey (Nasalis larvatus), (b) 3 ying lizard (Draco sp.), (c) Bornean bristlehead (Pityriasis gymnocephala). East of the line one 3 nds such species as (d) yellow-crested cockatoo (Cacatua sulphurea), (e) various tree kangaroos (Dendrolagus sp.), and (f) spotted cuscus (Spilocuscus maculates). Some of these species are either threatened or endangered. PLATE 2-2 These vertebrate animals are each endemic to the Galápagos Islands, but each traces its ancestry to animals living in South America. (a) and (b) Galápagos tortoise (Geochelone nigra). These two images show (a) a saddle-shelled tortoise and (b) a dome-shelled tortoise. -

Key to Common Mosquitoes Found in Early Season Ground Water

Key to Common Mosquitoes Found in Light Trap Collections in New Jersey Wayne J. Crans & Lisa M. Reed Rutgers the State University of New Jersey This key was prepared as a training tool for mosquito identification specialists whose primary job is to sort through light trap collections. The key may not be applicable for specimens that were collected as larvae and reared through to the adult stage. Caution should be used for specimens collected during landing rate and bite count collections. A number of species and species complexes that are common in light trap collections have been grouped. Wyeomyia smithii, and Toxorhynchites rutilus septentrionalis have not been included because they are not readily attracted to light. For simplification in the identification process, the following rare mosquito species on New Jersey’s checklist have been omitted: An. atropos, An. barberi, An. earlei, Oc. aurifer, Oc. communis, Oc. dorsalis,. Oc. dupreii, Oc. flavescens, Oc. hendersoni, Oc. implicatus, Oc. infirmatus, Oc. intrudens, Oc. mitchellae, Oc. provocans, Oc. spencerii, Oc. thibaulti, Ps. cyanescens, Ps. discolor, Ps. mathesoni, Cx. erraticus, Cx. tarsalis, and Cs. minnesotae. Aedes albopictus and Oc. japonicus rarely enter light traps but have been included because of their unique status as introduced exotics and their growing importance as pests The illustrations were scanned from plates in S.J. Carpenter and W.J. LaCasse 1955. “Mosquitoes of North America (North of Mexico”, University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles. Figures pertaining to Aedes albopictus and Ochlerotatus japonicus were scanned from Tanaka, K, K. Mizusawa and E.S. Saugstad. 1979, “A revision of the adult and larval mosquitoes of Japan (including the Ryukyu Archipelago and the Ogasawara Islands) and Korea”, Contributions of the American Entomological Institute, Vol. -

The Neogene Record of Northern South American Native Ungulates

Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press smithsonian contributions to paleobiology • number 101 Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press The Neogene Record of Northern South American Native Ungulates Juan D. Carrillo, Eli Amson, Carlos Jaramillo, Rodolfo Sánchez, Luis Quiroz, Carlos Cuartas, Aldo F. Rincón, and Marcelo R. Sánchez-Villagra SERIES PUBLICATIONS OF THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Emphasis upon publication as a means of “diffusing knowledge” was expressed by the first Secretary of the Smithsonian. In his formal plan for the Institution, Joseph Henry outlined a program that included the following statement: “It is proposed to publish a series of reports, giving an account of the new discoveries in science, and of the changes made from year to year in all branches of knowledge.” This theme of basic research has been adhered to through the years in thousands of titles issued in series publications under the Smithsonian imprint, commencing with Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge in 1848 and continuing with the following active series: Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology Smithsonian Contributions to Botany Smithsonian Contributions to History and Technology Smithsonian Contributions to the Marine Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to Museum Conservation Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology In these series, the Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press (SISP) publishes small papers and full-scale monographs that report on research and collections of the Institution’s museums and research centers. The Smithsonian Contributions Series are distributed via exchange mailing lists to libraries, universities, and similar institutions throughout the world. Manuscripts intended for publication in the Contributions Series undergo substantive peer review and evaluation by SISP’s Editorial Board, as well as evaluation by SISP for compliance with manuscript preparation guidelines (available at https://scholarlypress.si.edu). -

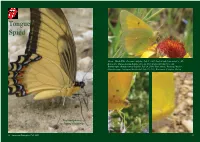

Tongue Spied

Tongue Spied Above: ‘Black Hills’ Christina’s Sulphur, July 5, 2007. Ditch Creek, Lawrence Co., SD. Below left: Orange-barred Sulphur. Oct. 21, 2007. Falcon SP, Starr Co., TX. Bottom right: Orange-barred Sulphur. July 29, 2009. Near Atoyac, Veracruz, Mexico. Opposite page: Androgeus Swallowtail. July 20, 2003. Bonampak, Chiapas, Mexico. Text and photos by Jeffrey Glassberg 32 American Butterflies,Fall 2009 33 Harvesters have strange, short gray tongues. April 23, 1994. Fork Creek WMA, Boone Co., WV. similar to what is found for eye color (also know of only one. Because they both have black) in swallowtails and contrasts with the white stripes across the FWs and HWs coupled greater heterogeneity of other families. with a large orange apical FW spot, female Most whites and yellows (53 species in 18 Pavon and Silver Emperors are often confused genera examined) seem to have tongue colors with Band-celled and Spot-celled Sisters. similar to those shown on page 33 — with the There are a number of ways to distinguish the color varying along the length of the tongue Doxocopa emperors from the sisters, but one Left: Oak Hairstreak. April 29, 2003. — pale at the base, darker in the middle and fun way is by their tongue color. Sisters have Goliad Co., TX. pale again at the end. Some however appear orange-yellow tongues (4 species examined; to have black tongues. see page 37, left) while emperors in the genus Within a species, tongue color can vary. Doxocopa have bright green tongues (4 Above: Ceraunus Blue. April 20, 2008. Note the somewhat differently colored tongues species examined; see photo, page 37 right). -

Structure of the Lepidopteran Proboscis in Relation to Feeding Guild

JOURNAL OF MORPHOLOGY 00:00–00 (2015) Structure of the Lepidopteran Proboscis in Relation to Feeding Guild Matthew S. Lehnert,1,2* Charles E. Beard,2 Patrick D. Gerard,3 Konstantin G. Kornev,4 and Peter H. Adler2 1Department of Biological Sciences, Kent State University at Stark, North Canton, Ohio 44720 2Department of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, Clemson University, Clemson, South Carolina 29634 3Department of Mathematical Sciences, Clemson University, Clemson, South Carolina 29634 4Department of Materials Science and Engineering, Clemson University, Clemson, South Carolina 29634 ABSTRACT Most butterflies and moths (Lepidoptera) (Monaenkova et al., 2012). A pump in the head use modified mouthparts, the proboscis, to acquire flu- then forces the liquid up the food canal to the gut ids. We quantified the proboscis architecture of five (Eberhard and Krenn, 2005; Borrell and Krenn, butterfly species in three families to test the hypothesis 2006; Lee et al., 2014). that proboscis structure relates to feeding guild. We Feeding guilds (i.e., groups of species with simi- used scanning electron microscopy to elucidate the fine structure of the proboscis of both sexes and to quantify lar feeding habits) have long been recognized in dimensions, cuticular patterns, and the shapes and the Lepidoptera and have been associated with sizes of sensilla and dorsal legulae. Sexual dimorphism higher taxa, such as nymphalid subfamilies or was not detected in the proboscis structure of any spe- tribes (Gilbert and Singer, 1975; Krenn et al., cies. A hierarchical clustering analysis of overall pro- 2001). Adult Lepidoptera are conventionally cate- boscis architecture reflected lepidopteran phylogeny, gorized into at least two broad feeding guilds: but did not produce a distinct group of flower visitors flower visitors (nectar feeders) and nonflower visi- or of puddle visitors within the flower visitors. -

Pollinator Traits of Highly Specialized Long-Spurred Orchids

Armament Imbalances: Match and Mismatch in Plant- Pollinator Traits of Highly Specialized Long-Spurred Orchids Marcela More´ 1, Felipe W. Amorim2*, Santiago Benitez-Vieyra1, A. Martin Medina1, Marlies Sazima3, Andrea A. Cocucci1 1 Laboratorio de Ecologı´a Evolutiva y Biologı´a Floral, Instituto Multidisciplinario de Biologı´a Vegetal, Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Cientı´ficas y Te´cnicas - Universidad Nacional de Co´rdoba, Co´rdoba, Argentina, 2 Programa de Po´s-Graduac¸a˜o em Biologia Vegetal, Departamento de Biologia Vegetal, Instituto de Biologia, Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Campinas, Sa˜o Paulo, Brasil, 3 Departamento de Biologia Vegetal, Instituto de Biologia, Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Campinas, Sa˜o Paulo, Brasil Abstract Background: Some species of long-spurred orchids achieve pollination by a close association with long-tongued hawkmoths. Among them, several Habenaria species present specialized mechanisms, where pollination success depends on the attachment of pollinaria onto the heads of hawkmoths with very long proboscises. However, in the Neotropical region such moths are less abundant than their shorter-tongued relatives and are also prone to population fluctuations. Both factors may give rise to differences in pollinator-mediated selection on floral traits through time and space. Methodology/Principal Findings: We characterized hawkmoth assemblages and estimated phenotypic selection gradients on orchid spur lengths in populations of three South American Habenaria species. We examined the match between hawkmoth proboscis and flower spur lengths to determine whether pollinators may act as selective agents on flower morphology. We found significant directional selection on spur length only in Habenaria gourlieana, where most pollinators had proboscises longer than the mean of orchid spur length. -

Repair of the Proboscis of Brush-Footed Butterflies (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae)" (2014)

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 8-2014 REPAIR OF THE PROBOSCIS OF BRUSH- FOOTED BUTTERFLIES (LEPIDOPTERA: NYMPHALIDAE) Suellen Pometto Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Part of the Entomology Commons Recommended Citation Pometto, Suellen, "REPAIR OF THE PROBOSCIS OF BRUSH-FOOTED BUTTERFLIES (LEPIDOPTERA: NYMPHALIDAE)" (2014). All Theses. 1881. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/1881 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REPAIR OF THE PROBOSCIS OF BRUSH-FOOTED BUTTERFLIES (LEPIDOPTERA: NYMPHALIDAE) ______________________________________ A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University ______________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science Entomology ______________________________________ by Suellen Floyd Pometto August 2014 ______________________________________ Accepted by: Dr. John C. Morse, Committee Co-Chair Dr. Peter H. Adler, Committee Co-Chair Dr. John Hains ABSTRACT A key feature of the order Lepidoptera is the coilable proboscis, present in over 99% of lepidopteran species. The proboscis is used to obtain liquid nutrition, usually floral nectar. The proboscis is assembled from two elongate galeae immediately after emergence of the adult from the pupa. What happens if the galeae become separated? I studied the process of repair of the proboscis, behaviorally and functionally, at the organismal level. My research questions were as follows: 1) is the proboscis capable of repair, 2) is saliva necessary to proboscis repair, and 3) is the repaired proboscis able to acquire fluids? Test organisms were Danaus plexippus (Linnaeus) (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae: Danainae) and Vanessa cardui (Linnaeus) (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae: Nymphalinae). -

The Phylogeny and Biogeography of the Monito Del Monte (Dromiciops Gliroides) and Its Relatives

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Honors College 5-2013 The Phylogeny and Biogeography of the Monito del Monte (Dromiciops Gliroides) and its Relatives Ariel Berthel University of Maine - Main Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors Part of the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, and the Zoology Commons Recommended Citation Berthel, Ariel, "The Phylogeny and Biogeography of the Monito del Monte (Dromiciops Gliroides) and its Relatives" (2013). Honors College. 117. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors/117 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PHYLOGENY AND BIOGEOGRAPHY OF THE MONITO DEL MONTE (DROMICIOPS GLIROIDES) AND ITS RELATIVES by Ariel Berthel A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a Degree with Honors (Zoology) The Honors College University of Maine May 2013 Advisory Committee: Irving L. Kornfield, Professor of Biology and Molecular Forensics William E. Glanz, Associate Professor of Zoology Seth Tyler, Professor of Zoology Edith Pratt Elwood, Honors College, faculty Karen A. Linehan, Department of Art, faculty Abstract Marsupials are a group of mammals that give birth to young that are not fully developed. These offspring must complete the remainder of their development outside of the womb attached to their mother’s teat. Marsupials only occur in South America and Australasia, with one species extending into North America. The marsupial known as the monito del monte, which is Spanish for ‘little monkey of the mountain,’ (Dromiciops gliroides) is a South American marsupial; however, it shares a key morphological feature of ankle bone morphology with Australasian marsupials. -

Chapter 13: the Flower and Sexual Reproduction

Chapter 13 The Flower and Sexual Reproduction THE FLOWER: SITE OF SEXUAL REPRODUCTION THE PARTS OF A COMPLETE FLOWER AND THEIR FUNCTIONS The Male Organs of the Flower Are the Androecium. The Female Organs of the Flower Are the Gynoecium The Embryo Sac Is the Female Gametophyte Plant Double Fertilization Produces an Embryo and the Endosperm APICAL MERISTEMS: SITES OF FLOWER DEVELOPMENT Flowers Vary in Their Architecture Often Flowers Occur in Clusters, or Inflorescences REPRODUCTIVE STRATEGIES: SELF- POLLINATION AND CROSS-POLLINATION Production of Some Seeds Does Not Require Fertilization Pollination Is Effected by Vectors SUMMARY PLANTS, PEOPLE AND THE ENVIRONMENT: Bee-Pollinated Flowers 1 KEY CONCEPTS 1. Sexual reproduction occurs in flowering plants in specialized structures called flowers. They are composed of four whorls of leaflike structures: the calyx (composed of sepals) serves a protective function; the corolla (composed of petals) usually functions to attract insects; the androecium (composed of stamens) is the male part of the flower; and the gynoecium (carpels or pistil) is the female part. 2. Stamens produce pollen. The stamen's female counterpart is the pistil, which is composed of the stigma (collects pollen), the style, and the ovary. The ovary produces eggs. 3. Sexual reproduction in plants involves pollination, which is the transfer of pollen from the anther of one flower to the stigma of the same or a different flower. The pollen lands on the stigma and grows into the style (as the pollen tube) until it penetrates the ovule and releases two sperm. 4. Double fertilization is unique to flowering plants. One sperm fuses to the egg to form the zygote; the other fuses to the polar nuclei to form the primary endosperm nucleus. -

Marine Flora and Fauna of the Eastern United States Acanthocephala

NOAA Technical Report NMFS 135 May 1998 Marine Flora and Fauna of the Eastern United States Acanthocephala OmarM.Amin ...... .'.':' .. "" . "1fD.. '.::' .' . u.s. Department of Commerce u.s. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE WILLIAM M. DALEY NOAA SECRETARY National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Technical D.James Baker Under Secretary for Oceans and Atmosphere Reports NMFS National Marine Fisheries Service Technical Reports of the Fishery Bulletin Rolland A. Schmitten Assistant Administrator for Fisheries Scientific Editor Dr. John B. Pearce Northeast Fisheries Science Center National Marine Fisheries Service, NOAA 166 Water Street Woods Hole, Massachusetts 02543-1097 Editorial Committee Dr. Andrew E. Dizon National Marine Fisheries Service Dr. Linda L. Jones National Marine Fisheries Service Dr. Richard D. Methot National Marine Fisheries Service Dr. Theodore W. Pietsch University of Washington Dr.Joseph E. Powers National Marine Fisheries Service Dr. Titn D. Smith National Marine Fisheries Service Managing Editor Shelley E. Arenas Scientific Publications Office National Marine Fisheries Service, NOAA 7600 Sand Point Way N.E. Seattle, Washington 98115-0070 The NOAA Technical Report NMFS (ISSN 0892-8908) series is published by the Scientific Publications Office, Na tional Marine Fisheries Service, NOAA, 7600 Sand Point Way N.E., Seattle, WA The ,NOAA Technical Report ,NMFS series of the Fishery Bulletin carries peer-re 98115-0070. viewed, lengthy original research reports, taxonomic keys, species synopses, flora The Secretary of Commerce has de and fauna studies, and data intensive reports on investigations in fishery science, termined that tlle publication of tlns se engineering, and economics. The series was established in 1983 to replace two ries is necessary in tl1e transaction of tlle subcategories of the Technical Report series: "Special Scientific Report-Fisher public business required by law of tllis ies" and "Circular." Copies of the ,NOAA Technical Report ,NMFS are available free Department. -

Mouth Parts of Insects.Pdf

MOUTH PARTS OF INSECTS Insects are the largest group of animals that occupy every type of habitat available on earth with the possible exception of sea. They also feed on a variety of food in different habitat condition. They are plant feeding, predators, parasitic and decomposers, for which they must possess different types of feeding apparatus. When the insects evolved, they had biting and chewing type of mouth parts to feed on the plant material available on land but as their food choices changed with time, these mouth parts modified to suit the type of food eaten. BITING & CHEWING TYPE or MANDIBULATE TYPE This type of mouth parts are found in cockroaches, grasshoppers, locusts, termites, wasps, book and bird lice, earwigs, dragonflies and other large number of insects. On the dorsal side there is an upper lip called labrum, which is attached to the base with the clypeus of face. This is a modified appendage of the 3rd body segment. The appendages of the 4th body segment are a pair of mandibles, which are broad containing sharp teeth for biting and chewing. The appendages of the 5 th segment are a pair of maxillae, which can also be called side lips. Each maxilla is made of a basal piece called cardo attached to stipes and palpiger, the last piece carries 3-4 segmented palp that carries chemoreceptors. At the apical end of the maxilla are attached galea and lacinia, the former functions like a cover and the latter is toothed and is used for chewing food. Labium is single median mouth part which has evolved by the fusion of the appendages of the 6th body segment.