Chapter 5 the Governance of Water Infrastructure in Chile

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Análisis De Una Eventual División De La V Región De Valparaíso

Análisis de una eventual división de la V región de Valparaíso basado en una hipótesis de recorte territorial: implicancias políticas, jurídicas, económicas, sociales, demográficas y medio ambientales1. La presente investigación, pretende ser una contribución con miras a dilucidar la viabilidad de una división de la actual V región de nuestro país. A objeto de lo señalado se efectuará una caracterización de la Región de Valparaíso y de sus Provincias, atendiendo factores históricos, políticos, económicos, geográficos y de población, entre otros. 1 Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional. Contacto: Rodrigo Obrador – Departamento de Estudios, Extensión y Publicaciones, BCN. E-Mail: [email protected], Anexo: 3115. 01-03-2012. Serie Estudios Nº 1-12. Participantes: David Vásquez, Rodrigo Obrador, Julio Vega, Felipe Rivera, María Teresa Corvera, Mauricio Amar, Edmundo Serani, Fernando Arrau, Marek Hohen y con la colaboración de Francisco Mardones (SIIT). i Tabla de Contenido I. INTRODUCCIÓN .........................................................................................................................................1 II. ANTECEDENTES HISTÓRICOS DE LA QUINTA REGIÓN DE VALPARAÍSO COMO UNIDAD DE LA DIVISIÓN POLÍTICA ADMINISTRATIVA (DPA) DEL ESTADO............................4 1. SIGLO XIX ..................................................................................................................................................4 2. SIGLO XX.....................................................................................................................................................4 -

Primer Tribunal Electoral De La Region Metropolitana

PRIMER TRIBUNAL ELECTORAL DE LA REGIÓN METROPOLITANA ESTADO CONFORME AL ART. 27 LEY N° 18.593 Pág.1/3 Santiago, 11 de octubre de 2018 ORDEN ROL N° ROL (en letras) RECLAMANTE - MATERIA RESOLUCIONES 1 6224 Seis mil doscientos veinticuatro Junta de Vecinos “Amapolas” de la comuna de Ñuñoa. Calificación elecciones. Sentencia 2 6321 Seis mil trescientos veintiuno CDL de Salud “Cesfam Quinta Bella” de la comuna de Recoleta. Calificación elecciones. Sentencia 3 6375 Seis mil trescientos setenta y cinco Club Deportivo “Fernando Collinao” de la comuna de Lo Prado. Calificación elecciones. Sentencia 4 6458 Seis mil cuatrocientos cincuenta y ocho Club de Adulto Mayor “Comienzo de una Vida” de la comuna de La Cisterna. Calificación elecciones. Sentencia Club Deportivo y Social “Seniors Villa España” de la comuna de Estación Central. Calificación 5 6463 Seis mil cuatrocientos sesenta y tres elecciones Sentencia 6 6465 Seis mil cuatrocientos sesenta y cinco Comité de Allegados “Juntos por Nuestra Casa” de la comuna de La Granja. Calificación elecciones. Sentencia Club Adulto Mayor, Cultural y Social “Los Años Dorados” de la comuna de Huechuraba. Calificación 7 6466 Seis mil cuatrocientos sesenta y seis elecciones. Sentencia 8 6468 Seis mil cuatrocientos sesenta y ocho Centro Cultural “Comunicacional TV 8 Peñalolén” de la comuna de Peñalolén. Calificación elecciones. Sentencia 9 6473 Seis mil cuatrocientos setenta y tres Club del Adulto Mayor “Pila del Ganso” de la comuna de Estación Central. Calificación elecciones. Sentencia Centro de Desarrollo Social “Esperanza del Mañana” de la comuna de La Granja. Calificación 10 6503 Seis mil quinientos tres elecciones. Sentencia 11 6607 Seis mil seiscientos siete Comité de Allegados “Fuerza y Coraje” de la comuna de Puente Alto. -

An Integrated Analysis of the March 2015 Atacama Floods

PUBLICATIONS Geophysical Research Letters RESEARCH LETTER An integrated analysis of the March 2015 10.1002/2016GL069751 Atacama floods Key Points: Andrew C. Wilcox1, Cristian Escauriaza2,3, Roberto Agredano2,3,EmmanuelMignot2,4, Vicente Zuazo2,3, • Unique atmospheric, hydrologic, and 2,3,5 2,3,6 2,3,7,8 2,3 9 geomorphic factors generated the Sebastián Otárola ,LinaCastro , Jorge Gironás , Rodrigo Cienfuegos , and Luca Mao fl largest ood ever recorded in the 1 2 Atacama Desert Department of Geosciences, University of Montana, Missoula, Montana, USA, Departamento de Ingeniería Hidráulica y 3 • The sediment-rich nature of the flood Ambiental, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, Chile, Centro de Investigación para la Gestión Integrada de resulted from valley-fill erosion rather Desastres Naturales (CIGIDEN), Santiago, Chile, 4University of Lyon, INSA Lyon, CNRS, LMFA UMR5509, Villeurbanne, France, than hillslope unraveling 5Civil and Environmental Engineering and Earth Sciences, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, Indiana, USA, 6Escuela de • Anthropogenic factors increased the fi 7 consequences of the flood and Ingeniería Civil, Ponti cia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso, Valparaíso, Chile, Centro de Desarrollo Urbano Sustentable 8 highlight the need for early-warning (CEDEUS), Santiago, Chile, Centro Interdisciplinario de Cambio Global, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, systems Chile, 9Departamento de Ecosistemas y Medio Ambiente, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, Chile Supporting Information: Abstract In March 2015 unusual ocean and atmospheric conditions produced many years’ worth of • Supporting Information S1 rainfall in a ~48 h period over northern Chile’s Atacama Desert, one of Earth’s driest regions, resulting in Correspondence to: catastrophic flooding. -

17.2 Present Situation and Outlook of Regional Integration Investments

17.2 Present Situation and Outlook of Regional Integration Investments and exports in the North Zone will be largely determined by the degree to which the macro-region is physically and institutionally integrated. At present, it is highly important to facilitate physical integration through the improvement of infrastructure and the transport system of export corridors. Institutional integration, e.g., standardized customs procedures, foreign investment laws, taxation systems, etc., is no less important than physical integration. Such development will widen and strengthen relations among economies of the macro-region and increase the possibility of handling export and import cargo and receiving foreign investment in the North Zone. Enterprises in the zone may also benefit from economies of scale while consumers will enjoy increases in the variety of goods and services available due to an expansion of their market. Cooperation between the private and public sectors and among central and local governments in the macro-region is indispensable for physical and institutional integration. This is because neither the private sector, nor the Chilean or regional governments of the North Zone, can carry out all necessary tasks alone. When the public sector renders support to improve physical and institutional infrastructure, particularly through international and inter-regional cooperation, the private sector’s interest in investing in the macro-region will be significantly increased. This will happen because such a situation will help investors minimize economic and political risks and maximize profits. 17.2.1 Regional Integration Schemes Institutional arrangements that can facilitate trade and investment in the macro-region include a customs union, a common market, a free trade agreement, a free trade zone, etc., but these schemes for regional economic integration are not new in South America. -

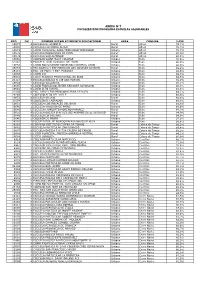

Rbd Dv Nombre Establecimiento

ANEXO N°7 FOCALIZACIÓN PROGRAMA ESCUELAS SALUDABLES RBD DV NOMBRE ESTABLECIMIENTO EDUCACIONAL AREA COMUNA %IVE 10877 4 ESCUELA EL ASIENTO Rural Alhué 74,7% 10880 4 ESCUELA HACIENDA ALHUE Rural Alhué 78,3% 10873 1 LICEO MUNICIPAL SARA TRONCOSO TRONCOSO Urbano Alhué 78,7% 10878 2 ESCUELA BARRANCAS DE PICHI Rural Alhué 80,0% 10879 0 ESCUELA SAN ALFONSO Rural Alhué 90,3% 10662 3 COLEGIO SAINT MARY COLLEGE Urbano Buin 76,5% 31081 6 ESCUELA SAN IGNACIO DE BUIN Urbano Buin 86,0% 10658 5 LICEO POLIVALENTE MODERNO CARDENAL CARO Urbano Buin 86,0% 26015 0 ESC.BASICA Y ESP.MARIA DE LOS ANGELES DE BUIN Rural Buin 88,2% 26111 4 ESC. DE PARV. Y ESP. PUKARAY Urbano Buin 88,6% 10638 0 LICEO 131 Urbano Buin 89,3% 25591 2 LICEO TECNICO PROFESIONAL DE BUIN Urbano Buin 89,5% 26117 3 ESCUELA BÁSICA N 149 SAN MARCEL Urbano Buin 89,9% 10643 7 ESCUELA VILLASECA Urbano Buin 90,1% 10645 3 LICEO FRANCISCO JAVIER KRUGGER ALVARADO Urbano Buin 90,8% 10641 0 LICEO ALTO JAHUEL Urbano Buin 91,8% 31036 0 ESC. PARV.Y ESP MUNDOPALABRA DE BUIN Urbano Buin 92,1% 26269 2 COLEGIO ALTO DEL VALLE Urbano Buin 92,5% 10652 6 ESCUELA VILUCO Rural Buin 92,6% 31054 9 COLEGIO EL LABRADOR Urbano Buin 93,6% 10651 8 ESCUELA LOS ROSALES DEL BAJO Rural Buin 93,8% 10646 1 ESCUELA VALDIVIA DE PAINE Urbano Buin 93,9% 10649 6 ESCUELA HUMBERTO MORENO RAMIREZ Rural Buin 94,3% 10656 9 ESCUELA BASICA G-N°813 LOS AROMOS DE EL RECURSO Rural Buin 94,9% 10648 8 ESCUELA LO SALINAS Rural Buin 94,9% 10640 2 COLEGIO DE MAIPO Urbano Buin 97,9% 26202 1 ESCUELA ESP. -

Resolución 31 AFECTA

Tipo Norma :Resolución 31 AFECTA; Resolución 31-4-35 AFECTA Fecha Publicación :17-08-1996 Fecha Promulgación :01-08-1996 Organismo :GOBIERNO REGIONAL V REGIÓN DE VALPARAÍSO Título :APRUEBA MODIFICACION AL PLAN REGULADOR INTERCOMUNAL;DE VALPARAISO, COMUNAS DE PUCHUNCAVI, ZAPALLAR, PAPUDO,;LA LIGUA, SATELITE BORDE COSTERO NORTE Tipo Versión :Única De : 17-08-1996 Inicio Vigencia :17-08-1996 Id Norma :32395 URL :https://www.leychile.cl/N?i=32395&f=1996-08-17&p= APRUEBA MODIFICACION AL PLAN REGULADOR INTERCOMUNAL DE VALPARAISO, COMUNAS DE PUCHUNCAVI, ZAPALLAR, PAPUDO, LA LIGUA, SATELITE BORDE COSTERO NORTE Núm. 31/4 35 afecta.- Valparaíso, 1° de agosto de 1996. Vistos: 1) El oficio ordinario N° 939 de 20 de junio de 1996 del Sr. Secretario Regional Ministerial de Vivienda y Urbanismo V Región. 2) El acuerdo N° 828 de 11 de julio de 1996, adoptado en la Sesión Ordinaria N° 105, del Consejo Regional V Región. 3) Lo dispuesto en los artículos 35, 36, 37, y 38 de la Ley General de Urbanismo y Construcciones, decreto supremo N° 458 de 1976 y Artículo 20, letra f), 24 letra o) y 36 letra c) de la Ley Orgánica Constitucional sobre Gobierno y Administración Regional, N° 19.175. Resuelvo: 1° Téngase por Aprobada la Modificación del Plan Regulador Intercomunal de Valparaíso, aprobado por decreto supremo N° 30 (M.O.P.) de 12.01.65, publicado en el Diario Oficial de fecha 01.03.65, en el sentido de: - Incorporar al Area Intercomunal de Valparaíso el territorio de las Comunas de Puchuncaví, Zapallar, Papudo y La Ligua, en la forma que a continuación se indica y a lo graficado en los Planos M.P.I.V. -

Submarine Tailings in Chile—A Review

metals Review Submarine Tailings in Chile—A Review Freddy Rodríguez 1, Carlos Moraga 2,*, Jonathan Castillo 3 , Edelmira Gálvez 4, Pedro Robles 5 and Norman Toro 1,* 1 Faculty of Engineering and Architecture, Universidad Arturo Prat, Almirante Juan José Latorre 2901, Antofagasta 1244260, Chile; [email protected] 2 Escuela de Ingeniería Civil de Minas, Facultad de Ingeniería, Universidad de Talca, Curicó 3340000, Chile 3 Departamento de Ingeniería en Metalurgia, Universidad de Atacama, Av. Copayapu 485, Copiapó 1531772, Chile; [email protected] 4 Departamento de Ingeniería Metalúrgica y Minas, Universidad Católica del Norte, Antofagasta 1270709, Chile; [email protected] 5 Escuela De Ingeniería Química, Pontificia Universidad Católica De Valparaíso, Valparaíso 2340000, Chile; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (C.M.); [email protected] (N.T.); Tel.: +56-552651021 (N.T.) Abstract: This review aims to understand the environmental impact that tailings produce on the land and marine ecosystem. Issues related to flora, fauna, and the environment are revised. In the first instance, the origin of the treatment and disposal of marine mining waste in Chile and other countries is studied. The importance of tailings’ valuable elements is analyzed through mineralogy, chemical composition, and oceanographic interactions. Several tailings’ treatments seek to recover valuable minerals and mitigate environmental impacts through leaching, bioleaching, and flotation methods. The analysis was complemented with the particular legislative framework for every country, highlighting those with formal regulations for the disposal of tailings in a marine environment. The available registry on flora and fauna affected by the discharge of toxic metals is explored. As a study Citation: Rodríguez, F.; Moraga, C.; case, the “Playa Verde” project is detailed, which recovers copper from marine tailings, and uses Castillo, J.; Gálvez, E.; Robles, P.; Toro, phytoremediation to neutralize toxic metals. -

Groundwater Origin and Recharge in the Hyperarid Cordillera De La Costa, Atacama Desert, Northern Chile

Groundwater origin and recharge in the hyperarid Cordillera de la Costa, Atacama Desert, northern Chile. Christian Herrera1,2, Carolina Gamboa1,2, Emilio Custodio3, Teresa Jordan4, Linda Godfrey5, Jorge Jódar6, José A. Luque1,2, Jimmy Vargas7, Alberto Sáez8 1 Departmento de Ciencias Geológicas , Universidad Católica del Norte, Antofagasta, Chile 2 CEITSAZA‐Research and Technological Center of Water in the Desert, Northern Catholic University, Antofagasta, Chile 3 Groundwater Hydrology Group, Dept. Civil and Environmental Eng., Technical University of Catalonia (UPC). Royal Academy of Sciences of Spain 4 Department of Earth & Atmospheric Sciences and Atkinson Center for a Sustainable Future, Snee Hall, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853‐1504, USA 5 Earth and Planetary Sciences, Rutgers University, 610 Taylor Road, Piscataway, NJ 08854, USA. 6 Groundwater Hydrology Group, Dept. Civil and Environmental Eng., Technical University of Catalonia (UPC), Hydromodel Host S.L. and Aquageo Proyectos S.L., Spain 7 Mining Company Los Pelambres, Av. Apoquindo 4001 Piso 18, Las Condes, Santiago, Chile 8 Department of Earth and Ocean Dynamics, University of Barcelona, C. Martí i Franqués s/n, 08028 Barcelona, Spain GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT 1 Highlights ‐Small springs have been recognized in the hyper‐arid coastal zone of the Atacama Desert ‐The δ18O and δ2H values of spring waters are similar to coastal region rainfall ‐The average residence time of the waters from springs varies between 1 and 2 hyr, up to 5 hyr ‐Waters from the deep wells are isotopically much heavier than those of springs ‐Turnover time for deep waters varies between 7 and 13 hyr, which overlaps the CAPE events ABSTRACT The Cordillera de la Costa is located along the coastline of northern Chile, in the hyperarid Atacama Desert area. -

Downloaded 10/10/21 07:22 PM UTC Projects, but Has Also Built up a Public Meteorologi- Cal Database Over Previ- Ously Data-Void Regions

WIND ENERGY EXPLORATION OVER THE ATACAMA DESERT A Numerical Model–Guided Observational Program RICARDO C. MUÑOZ, MARK J. FALVEY, MARIO ARANCIBIA, VALENTINA I. ASTUDILLO, JAVIER ELGUETA, MARCELO IBARRA, CHRISTIAN SANTANA, AND CAMILA VÁSQUEZ A Chilean program explores winds over the Atacama Desert region and is producing a public model and observational database in support of the development of wind energy projects. enewable energy, especially wind and solar, is an and execute measurement programs, and for the increasingly important field in applied meteorol- modeling of resource variability. Renewable energy Rogy and climate science. From the initial studies poses special challenges compared to more traditional that explore the availability of these energy resources meteorological applications (Emeis 2013). In the case in a given area, to the forecasting models required of wind power, for example, most phenomena of inter- to optimize the operation of wind or solar power est occur within the atmospheric boundary layer over plants, meteorological expertise is needed to design horizontal scales ranging from the microscale to the mesoscale. Moreover, the viability of many renew- able energy projects depends on the accuracy of the AFFILIATIONS: MUÑOZ AND ASTUDILLO—Department of Geophys- ics, University of Chile, Santiago, Chile; FALVEY AND IBARRA—De- meteorological variables measured and modeled, with partment of Geophysics, University of Chile, and Meteodata Ltd., even small errors having large financial implications. Santiago, Chile; ARANCIBIA AND ELGUETA—Department of Geophysics, On the other hand, the emergence of the renewable University of Chile, and Airtec Ltd., Santiago, Chile; SANTANA AND energy industry has led to a significant increase in the VÁSQUEZ—Ministerio de Energía, Santiago, Chile number of measuring sites being deployed worldwide, CORRESPONDING AUTHOR: Ricardo C. -

Valparaiso.Pdf

REGION PROVINCIA COMUNA AREA LOCAL CENSAL DIRECCION NUMERO VALPARAÍSO SAN ANTONIO ALGARROBO URBANO ADULTO MAYOR AÑOS DORADOSPASAJE ALBERTO HURTADO 170 VALPARAÍSO SAN ANTONIO ALGARROBO URBANO CENTRO DE REHABILITACIÓN RENACERAV. AGUAS MARINAS S/N VALPARAÍSO SAN ANTONIO ALGARROBO URBANO CLUB DE ADULTO MAYOR DE ALGARROBOLOS CEREZOS 1080 VALPARAÍSO SAN ANTONIO ALGARROBO URBANO COLEGIO CARLOS ALESSANDRI ALTAMIRANOEL OLMO 1599 VALPARAÍSO SAN ANTONIO ALGARROBO URBANO JARDÍN INFANTIL MIRASOL AV. MIRASOL S/N VALPARAÍSO SAN ANTONIO ALGARROBO URBANO JUNTA DE VECINOS 4-2 EL YECOLIBERTADORES - SEDE JUNTA DECON VECINOS ISABEL RIQUELMEEL YECO S/N VALPARAÍSO SAN ANTONIO ALGARROBO URBANO JUNTA DE VECINOS LAS TINAJASYUCATÁN DEL CANELO 1535 VALPARAÍSO SAN ANTONIO ALGARROBO URBANO MUNICIPALIDAD DE ALGARROBOCARLOS - CASA ALESSANDRI DE LA CULTURA 1633 VALPARAÍSO SAN ANTONIO ALGARROBO URBANO MUNICIPALIDAD DE ALGARROBOAV. - OFICINAPEÑABLANCA PRINCIPAL 250, ALGARROBO REGIÓN:V 250VALPARAÍSO VALPARAÍSO SAN ANTONIO ALGARROBO RURAL COLEGIO PUKALAN DE ALGARROBOCAMINO EL TOTORAL ESQUINA 12 DE LA FAMA 12S/N VALPARAÍSO SAN ANTONIO ALGARROBO RURAL ESCUELA BASICA RURAL SAN JOSEKILOMETRO 20 CAMINO LAS DICHAS S/N SN VALPARAÍSO SAN ANTONIO ALGARROBO RURAL ESCUELA PARTICULAR SAN JOSECAMINO MIRASOL KM 21 S/N VALPARAÍSO PETORCA CABILDO URBANO ESCUELA BASICA VALLE DE ARTIFICIOCALLE MANUEL MONTT S/N VALPARAÍSO PETORCA CABILDO URBANO ESCUELA HANS WENKE MENGERSPOBLACIÓN CERRO NEGRO PASAJE LA QUINTRALA560 VALPARAÍSO PETORCA CABILDO URBANO LICEO BICENTENARIO TECNICO AVDA.PROFESIONAL HUMERES DE MINERIA 1510 VALPARAÍSO PETORCA CABILDO URBANO LICEO Y ESCUELA MUNICIPAL ZOILA GAC 639 VALPARAÍSO PETORCA CABILDO RURAL ESCUELA BASICA G-45 CAMINO A ALICAHUE KM. 13 LA VEGA S/N VALPARAÍSO PETORCA CABILDO RURAL ESCUELA BASICA G-47 GUAYACAN, CAMINO A CERRO NEGRO S/N VALPARAÍSO PETORCA CABILDO RURAL ESCUELA BASICA LA FRONTERA CASASDE ALICAHUE ALICAHUE KM. -

Chile's Mining and Chemicals Industries

Global Outlook Chile’s Mining and Chemicals Industries Luis A. Cisternas With abundant mineral resources, Chile’s Univ. of Antofagasta Edelmira D. Gálvez chemicals industries are dominated by mining, Catholic Univ. of the North with many of its operations among the world’s most productive and important. hile’s chemicals industries consist of 300 companies producer. Chilean mining continues to reach unprecedented and some 400 products, with sales representing 4% levels — not only the mining of copper, but particularly Cof the nation’s gross domestic product (GDP) and of nonmetallic ores. Recent growth has been supported by about 25% of all industrial contributions to the GDP (1). favorable economic policies and incentives for foreign inves- Chile’s major chemical exports include methanol, inorganic tors that were intended to overcome the lack of domestic compounds (nitrates, iodine, lithium products, sodium investment after Chile’s return to democracy in the 1990s. chloride), combustibles (gasoline, diesel, fuel oil), algae Chile’s main metallic and nonmetallic ore deposits are derivatives, and plastic resins (polypropylene, low-density located in the country’s northern regions, which are rich in polyethylene). However, the mining industry — consisting copper, gold, silver, and iron deposits, as well as salt lake of 100 large and medium-sized companies and more than mineral byproducts such as nitrates, boron, iodine, lithium, 1,600 mining operations (2) — dominates Chile’s chemical- and potassium. Chile’s abundance of mineral resources is industry landscape. These companies’ primary products remarkable: Its reserves constitute 6.7% of the world’s gold, include molybdenum, rhenium, iron, lithium, silver, gold, 12.1% of the molybdenum, 13.3% of the silver, 27.7% of the and — most important — copper. -

Listado De Proyectistas Y Contratistas Siss, Vigentes Al 06 De Noviembre De 2017

LISTADO DE PROYECTISTAS Y CONTRATISTAS SISS, VIGENTES AL 06 DE NOVIEMBRE DE 2017 Información disponible en www.siss.cl: "http://www.siss.gob.cl/appsiss/Instaladores/listado.asp?region=5" Ciudad Comuna Nombre RUT Dirección Contratista Proyectista Teléfono Situación LOS ANDES CALLE LARGA RUIZ BAHAMONDES FEDERICO 10113323 PATAGUAL Nº 1 G 94847614 BENJAMIN LOS ANDES LOS ANDES AYALA ABARCA CARMELO ANTONIO 5096610 CORDILLERA 47, POB VIA LIBRE G G 9-81386691- [email protected] LOS ANDES LOS ANDES AYALA SALDIVAR JUAN CARLOS 9068307 OSCAR GRANADINO 1053 POB. G 34246379/ 88266656 BELLAVISTA LOS ANDES LOS ANDES DIAZ PIZARRO JUAN GUSTAVO 6520089 PJE. JOSE MARIA INFANTE No. 71, E G 75548717 VILLA BICENTENARIO LOS ANDES LOS ANDES SALAMANCA SILVA MAURICIO 9296710 AV. HECTOR HUMERES N°572, POB. G 999001697 - SERGIO LAS BODEGAS II [email protected] PETORCA CABILDO AGUILERA MUÑOZ GONZALO RAUL 11515559 NICANOR ESCOBAR No. 2056, LA G [email protected] RINCONADA PETORCA CABILDO DIAZ MENA HECTOR ALBINO DEL 4868874 SAN LORENZO N°725 G 33761906 - 998712163 TRANSITO PETORCA CABILDO VALENCIA MOLINA RAMIRO 10892138 SANTA FILOMENA 1 EL ESFUERZO - G 95421394 SERVANDO CASA Nº1 PETORCA LA LIGUA ASPE FREDES CAMILO ENRIQUE 7000208 ALICAHUE 151 VILLA O"HIGGINS G G 09-7239454 711388 PETORCA LA LIGUA GUTIERREZ LEIVA EDUARDO 6953831 PJE. 4 INTERIOR N°366, LOS MOLLES G 53694698 ENRIQUE PETORCA LA LIGUA LEIVA JELVES MANUEL ERNESTO 6291369 POLANCO 398 G 332711941 PETORCA LA LIGUA OLIVARES GARCIA HUGO ALBERTO 9179366 PJE 7 N°310 VILLA FUTURO G 99590437 PETORCA LA LIGUA OLIVARES OLIVARES JAIME 10292718 PJE.12 DE OCTUBRE S/N° SECTOR LA G 099601804 - EVARISTO GRUTA [email protected] PETORCA LA LIGUA OLIVARES RODRIGUEZ MANUEL 12578037 PASAJE ANA CRUCHAGA 288 VILLA G 33-2717658 - 92282927 - ALEJANDRO PADRE HURTADO [email protected] PETORCA LA LIGUA RAMOS ARANCIBIA JAIME DARIO 6734389 PJE.