Submarine Tailings in Chile—A Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Integrated Analysis of the March 2015 Atacama Floods

PUBLICATIONS Geophysical Research Letters RESEARCH LETTER An integrated analysis of the March 2015 10.1002/2016GL069751 Atacama floods Key Points: Andrew C. Wilcox1, Cristian Escauriaza2,3, Roberto Agredano2,3,EmmanuelMignot2,4, Vicente Zuazo2,3, • Unique atmospheric, hydrologic, and 2,3,5 2,3,6 2,3,7,8 2,3 9 geomorphic factors generated the Sebastián Otárola ,LinaCastro , Jorge Gironás , Rodrigo Cienfuegos , and Luca Mao fl largest ood ever recorded in the 1 2 Atacama Desert Department of Geosciences, University of Montana, Missoula, Montana, USA, Departamento de Ingeniería Hidráulica y 3 • The sediment-rich nature of the flood Ambiental, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, Chile, Centro de Investigación para la Gestión Integrada de resulted from valley-fill erosion rather Desastres Naturales (CIGIDEN), Santiago, Chile, 4University of Lyon, INSA Lyon, CNRS, LMFA UMR5509, Villeurbanne, France, than hillslope unraveling 5Civil and Environmental Engineering and Earth Sciences, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, Indiana, USA, 6Escuela de • Anthropogenic factors increased the fi 7 consequences of the flood and Ingeniería Civil, Ponti cia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso, Valparaíso, Chile, Centro de Desarrollo Urbano Sustentable 8 highlight the need for early-warning (CEDEUS), Santiago, Chile, Centro Interdisciplinario de Cambio Global, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, systems Chile, 9Departamento de Ecosistemas y Medio Ambiente, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, Chile Supporting Information: Abstract In March 2015 unusual ocean and atmospheric conditions produced many years’ worth of • Supporting Information S1 rainfall in a ~48 h period over northern Chile’s Atacama Desert, one of Earth’s driest regions, resulting in Correspondence to: catastrophic flooding. -

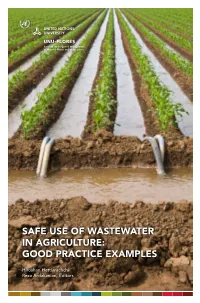

Safe Use of Wastewater in Agriculture: Good Practice Examples

SAFE USE OF WASTEWATER IN AGRICULTURE: GOOD PRACTICE EXAMPLES Hiroshan Hettiarachchi Reza Ardakanian, Editors SAFE USE OF WASTEWATER IN AGRICULTURE: GOOD PRACTICE EXAMPLES Hiroshan Hettiarachchi Reza Ardakanian, Editors PREFACE Population growth, rapid urbanisation, more water intense consumption patterns and climate change are intensifying the pressure on freshwater resources. The increasing scarcity of water, combined with other factors such as energy and fertilizers, is driving millions of farmers and other entrepreneurs to make use of wastewater. Wastewater reuse is an excellent example that naturally explains the importance of integrated management of water, soil and waste, which we define as the Nexus While the information in this book are generally believed to be true and accurate at the approach. The process begins in the waste sector, but the selection of date of publication, the editors and the publisher cannot accept any legal responsibility for the correct management model can make it relevant and important to any errors or omissions that may be made. The publisher makes no warranty, expressed or the water and soil as well. Over 20 million hectares of land are currently implied, with respect to the material contained herein. known to be irrigated with wastewater. This is interesting, but the The opinions expressed in this book are those of the Case Authors. Their inclusion in this alarming fact is that a greater percentage of this practice is not based book does not imply endorsement by the United Nations University. on any scientific criterion that ensures the “safe use” of wastewater. In order to address the technical, institutional, and policy challenges of safe water reuse, developing countries and countries in transition need clear institutional arrangements and more skilled human resources, United Nations University Institute for Integrated with a sound understanding of the opportunities and potential risks of Management of Material Fluxes and of Resources wastewater use. -

Notobaccolitter.Com

NEWSLETTER ARTICLE Possible Headlines: Tobacco Litter is More Than Just an Eyesore Tobacco Litter is Toxic Waste Tobacco Toxins Get Into More Than Just Your Lungs Take a short walk down the street, through a park or a beach and you’re bound to see it… cigarette butts, cigar tips, even cellophane wrappers and packaging, also known as…tobacco litter. Environmental cleanups consistently report cigarette butts as the number one picked up item. More than 12,000 cigarette butts were collected along Maryland beaches during a recent International Coastal Cleanup. Many people don’t see cigarette butts as litter and don’t realize their toxicity – leading some people to believe disposing of their tobacco on the ground is harmless. The truth is cigarette toxins get into more than just our lungs. Cigarette filters contain cellulose acetate – a plastic material that makes butts slow to degrade, if they degrade at all. Tobacco litter is more than just an eyesore; it’s toxic waste leaching heavy metals and chemicals such as lead and cyanide into our environment, poisoning our water and our communities where we live, work, and play. Tobacco litter is an issue that deserves increased awareness to promote healthy and safe communities. Help raise awareness about the toxic tobacco litter problem and provide another good reason to quit smoking or not start at all—for the health of your lungs, your community, and the environment! For more information on the toxicity of tobacco litter and ways you can help, visit: www.NoTobaccoLitter.com. If you or a loved one are ready to quit tobacco use, call 1-800-QUIT-NOW or visit: www.SmokingStopsHere.com. -

Mining's Toxic Legacy

Mining’s Toxic Legacy An Initiative to Address Mining Toxins in the Sierra Nevada Acknowledgements _____________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________ The Sierra Fund would like to thank Dr. Carrie Monohan, contributing author of this report, and Kyle Leach, lead technical advisor. Thanks as well to Dr. William M. Murphy, Dr. Dave Brown, and Professor Becky Damazo, RN, of California State University, Chico for their research into the human and environmental impacts of mining toxins, and to the graduate students who assisted them: Lowren C. McAmis and Melinda Montano, Gina Grayson, James Guichard, and Yvette Irons. Thanks to Malaika Bishop and Roberto Garcia for their hard work to engage community partners in this effort, and Terry Lowe and Anna Reynolds Trabucco for their editorial expertise. For production of this report we recognize Elizabeth “Izzy” Martin of The Sierra Fund for conceiving of and coordinating the overall Initiative and writing substantial portions of the document, Kerry Morse for editing, and Emily Rivenes for design and formatting. Many others were vital to the development of the report, especially the members of our Gold Ribbon Panel and our Government Science and Policy Advisors. We also thank the Rose Foundation for Communities and the Environment and The Abandoned Mine Alliance who provided funding to pay for a portion of the expenses in printing this report. Special thanks to Rebecca Solnit, whose article “Winged Mercury and -

Fighting Environmental Racism

FIGHTING ENVIRONMENTAL RACISM: A SELECTED ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY Irwin Weintraub <[email protected]> Library of Science and Medicine, Rutgers University, P O Box 1029, Piscataway, New Jersey 08855-1029 USA. TEL: 908-932-3526 Introduction Environmental racism can be defined as the intentional siting of hazardous waste sites, landfills, incinerators, and polluting industries in communities inhabited mainly by African-American, Hispanics, Native Americans, Asians, migrant farm workers, and the working poor. Minorities are particularly vulnerable because they are perceived as weak and passive citizens who will not fight back against the poisoning of their neighborhoods in fear that it may jeopardize jobs and economic survival. The landmark study, Toxic Wastes and Race in the United States (Commission for Racial Justice, United Church of Christ 1987), described the extent of environmental racism and the consequences for those who are victims of polluted environments. The study revealed that: Race was the most significant variable associated with the location of hazardous waste sites. The greatest number of commercial hazardous facilities were located in communities with the highest composition of racial and ethnic minorities. The average minority population in communities with one commercial hazardous waste facility was twice the average minority percentage in communities without such facilities. Although socioeconomic status was also an important variable in the location of these sites, race was the most significant even after controlling for urban and regional differences. The report indicated that three out of every five Black and Hispanic Americans lived in communities with one or more toxic waste sites. Over 15 million African-American, over 8 million Hispanics, and about 50 percent of Asian/Pacific Islanders and Native Americans are living in communities with one or more abandoned or uncontrolled toxic waste sites. -

Health Effects of Residence Near Hazardous Waste Landfill Sites: a Review of Epidemiologic Literature

Health Effects of Residence Near Hazardous Waste Landfill Sites: A Review of Epidemiologic Literature Martine Vrijheid Environmental Epidemiology Unit, Department of Public Health and Policy, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, United Kingdom This review evaluates current epidemiologic literature on health effects in relation to residence solvents, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), near landfill sites. Increases in risk of adverse health effects (low birth weight, birth defects, certain and heavy metals, have shown adverse effects types of cancers) have been reported near individual landfill sites and in some multisite studies, on human health or in animal experiments. and although biases and confounding factors cannot be excluded as explanations for these A discussion of findings from either epi findings, they may indicate real risks associated with residence near certain landfill sites. A general demiologic or toxicologic research on health weakness in the reviewed studies is the lack of direct exposure measurement. An increased effects related to specific chemicals is beyond prevalence of self-reported health symptoms such as fatigue, sleepiness, and headaches among the scope of this review. residents near waste sites has consistently been reported in more than 10 of the reviewed papers. It is difficult to conclude whether these symptoms are an effect of direct toxicologic action of Epidemiologic Studies on chemicals present in waste sites, an effect of stress and fears related to the waste site, or an Health Effects of Landfill Sites risks to effect of reporting bias. Although a substantial number of studies have been conducted, The majority of studies evaluating possible is insufficient exposure information and effects health from landfill sites are hard to quantify. -

III . Waste Management

III. WASTE MANAGEMENT Economic growth, urbanisation and industrialisation result in increasing volumes and varieties of both solid and hazardous wastes. Globalisation can aggravate waste problems through grow ing international waste trade, with developing countries often at the receiving end. Besides negative impacts on health as well as increased pollution of air, land and water, ineffective and inefficient waste management results in greenhouse gas and toxic emissions, and the loss of precious materials and resources. Pollution is nothing but An integrated waste management approach is a crucial part of interna- the resources we are not harvesting. tional and national sustainable development strategies. In a life-cycle per- We allow them to disperse spective, waste prevention and minimization generally have priority. The because we’ve been remaining solid and hazardous wastes need to be managed with effective and efficient measures, including improved reuse, recycling and recovery ignorant of their value. of useful materials and energy. — R. Buckminster Fuller The 3R concept (Reduce, Reuse, Recycle) encapsulates well this life-cycle Scientist (1895–1983) approach to waste. WASTE MANAGEMENT << 26 >> Hazardous waste A growing share of municipal waste contains hazardous electronic or electric products. In Europe ewaste is increasing by 3–5 per Hazardous waste, owing to its toxic, infectious, radioactive or flammable cent per year. properties, poses an actual or potential hazard to the health of humans, other living organisms, or the environment. According to UNEP, some 20 to 50 million metric tonnes of e-waste are generated worldwide every year. Other estimates expect computers, No data on hazardous waste generation are available for most African, mobile telephones and television to contribute 5.5 million tonnes to Middle Eastern and Latin American countries. -

Dyes and Pigments Manufacturing Industrial Waste Water Treatment Methodology

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056 Volume: 04 Issue: 12 | Dec-2017 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072 DYES AND PIGMENTS MANUFACTURING INDUSTRIAL WASTE WATER TREATMENT METHODOLOGY ROOP SINGH LODHI1, NAVNEETA LAL2 1DEPARTMENT OF CHEMICAL ENGINEERING, UJJAIN ENGINEERING COLLEGE UJJAIN, (M.P.), INDIA 2ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR CHEMICAL ENGINEERING DEPARTMENT UJJAIN ENGINEERING COLLEGE UJJAIN, (M.P.), INDIA ---------------------------------------------------------------------***--------------------------------------------------------------------- ABSTRACT - Chemical coagulation- flocculation was used not defined by this definition of dyes and pigments are called to remove the compounds present in wastewater from dye dyestuffs. Synthetic organic dyestuffs and pigments exhibit manufacturing industry. The character of wastewater was an extremely wide variety of physical, chemical and determined as its contained high ammonia (5712mg/L), COD biological properties, making review of the Eco toxicological (38000mg/L) and Total dissolved solids (56550mg/L) behaviour of the several thousand commercially available concentration. Most compounds found in the wastewater are products difficult, production process are difficult to control ammonia, phenol derivatives, aniline derivatives, organic acid the release of manufacturing material during dye and benzene derivatives output from dyes and pigment manufacturing [1-13]. Industrial waste water is one of the manufacturing industries. Coagulants ferrous sulphate, ferric important pollution sources in the pollution of water, soil chloride, Polly-aluminium chloride, and hydrogen peroxide and environment. It not only affects the ecosystem but also catalysed by ferrous sulphate and flocculants lime and NaOH affects the human life .so it is necessary to treat the waste were investigated. Results showed the combined Fe (III) water before discharging it into the ecosystem by chloride and Polly aluminium chloride with NaOH for considering the financial aspects in mind. -

Executive Summary

Executive Summary BACKGROUND The use of treated municipal wastewater effluent for irrigated agriculture offers an op-portunity to conserve water resources. Water reclamation can also provide an alternative to disposal in areas where surface waters have a limited capacity to assimilate the contaminants, such as the nitrogen and phosphorus, that remain in most treated wastewater effluent discharges. The sludge that results from municipal wastewater treatment processes contains organic matter and nutrients that, when properly treated and applied to farmland, can improve the physical properties and agricultural productivity of soils, and its agricultural use provides an alternative to disposal options, such as incineration, or landfilling. Land application of municipal wastewater and sludge has been practiced for its beneficial effects and for disposal purposes since the advent of modern wastewater management about 150 years ago. Not surprisingly, public response to the practice has been mixed. Raw municipal wastewater contains human pathogens and toxic chemicals. With continuing advances in waste-water treatment technology and increasingly stringent wastewater discharge requirements, most treated wastewater effluents produced by public treatment authorities in the United States are now of consistent, high quality. When treated to acceptable levels or by appropriate processes to meet state reuse requirements, the effluent is referred to as "reclaimed water." Sewage sludge can also be treated to levels that allow it to be reused. With the increased interest in reclaimed water and the promotion of agricultural use for treated sludge, there has been increased public scrutiny of the potential health and environmental consequences of these reuse practices. Farmers and the food industry have expressed their concerns that such practices—especially the agricultural use of sludge—may affect the safety of food products and the sustainability of agricultural land, and may carry potential economic and liability risks. -

Groundwater Origin and Recharge in the Hyperarid Cordillera De La Costa, Atacama Desert, Northern Chile

Groundwater origin and recharge in the hyperarid Cordillera de la Costa, Atacama Desert, northern Chile. Christian Herrera1,2, Carolina Gamboa1,2, Emilio Custodio3, Teresa Jordan4, Linda Godfrey5, Jorge Jódar6, José A. Luque1,2, Jimmy Vargas7, Alberto Sáez8 1 Departmento de Ciencias Geológicas , Universidad Católica del Norte, Antofagasta, Chile 2 CEITSAZA‐Research and Technological Center of Water in the Desert, Northern Catholic University, Antofagasta, Chile 3 Groundwater Hydrology Group, Dept. Civil and Environmental Eng., Technical University of Catalonia (UPC). Royal Academy of Sciences of Spain 4 Department of Earth & Atmospheric Sciences and Atkinson Center for a Sustainable Future, Snee Hall, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853‐1504, USA 5 Earth and Planetary Sciences, Rutgers University, 610 Taylor Road, Piscataway, NJ 08854, USA. 6 Groundwater Hydrology Group, Dept. Civil and Environmental Eng., Technical University of Catalonia (UPC), Hydromodel Host S.L. and Aquageo Proyectos S.L., Spain 7 Mining Company Los Pelambres, Av. Apoquindo 4001 Piso 18, Las Condes, Santiago, Chile 8 Department of Earth and Ocean Dynamics, University of Barcelona, C. Martí i Franqués s/n, 08028 Barcelona, Spain GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT 1 Highlights ‐Small springs have been recognized in the hyper‐arid coastal zone of the Atacama Desert ‐The δ18O and δ2H values of spring waters are similar to coastal region rainfall ‐The average residence time of the waters from springs varies between 1 and 2 hyr, up to 5 hyr ‐Waters from the deep wells are isotopically much heavier than those of springs ‐Turnover time for deep waters varies between 7 and 13 hyr, which overlaps the CAPE events ABSTRACT The Cordillera de la Costa is located along the coastline of northern Chile, in the hyperarid Atacama Desert area. -

Downloaded 10/10/21 07:22 PM UTC Projects, but Has Also Built up a Public Meteorologi- Cal Database Over Previ- Ously Data-Void Regions

WIND ENERGY EXPLORATION OVER THE ATACAMA DESERT A Numerical Model–Guided Observational Program RICARDO C. MUÑOZ, MARK J. FALVEY, MARIO ARANCIBIA, VALENTINA I. ASTUDILLO, JAVIER ELGUETA, MARCELO IBARRA, CHRISTIAN SANTANA, AND CAMILA VÁSQUEZ A Chilean program explores winds over the Atacama Desert region and is producing a public model and observational database in support of the development of wind energy projects. enewable energy, especially wind and solar, is an and execute measurement programs, and for the increasingly important field in applied meteorol- modeling of resource variability. Renewable energy Rogy and climate science. From the initial studies poses special challenges compared to more traditional that explore the availability of these energy resources meteorological applications (Emeis 2013). In the case in a given area, to the forecasting models required of wind power, for example, most phenomena of inter- to optimize the operation of wind or solar power est occur within the atmospheric boundary layer over plants, meteorological expertise is needed to design horizontal scales ranging from the microscale to the mesoscale. Moreover, the viability of many renew- able energy projects depends on the accuracy of the AFFILIATIONS: MUÑOZ AND ASTUDILLO—Department of Geophys- ics, University of Chile, Santiago, Chile; FALVEY AND IBARRA—De- meteorological variables measured and modeled, with partment of Geophysics, University of Chile, and Meteodata Ltd., even small errors having large financial implications. Santiago, Chile; ARANCIBIA AND ELGUETA—Department of Geophysics, On the other hand, the emergence of the renewable University of Chile, and Airtec Ltd., Santiago, Chile; SANTANA AND energy industry has led to a significant increase in the VÁSQUEZ—Ministerio de Energía, Santiago, Chile number of measuring sites being deployed worldwide, CORRESPONDING AUTHOR: Ricardo C. -

TROUBLED WATERS How Mine Waste Dumping Is Poisoning Our Oceans, Rivers, and Lakes

TROUBLED WATERS HOW MINE WASTE DUMPING IS POISONING OUR OCEANS, RIVERS, AND LAKES Earthworks and MiningWatch Canada, February 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................1 TABLE 1. WATER BODIES IMPERILED BY CURRENT OR PROPOSED TAILINGS DUMPING ................................. 2 TABLE 2. MINING CORPORATIONS THAT DUMP TAILINGS INTO NATURAL WATER BODIES .......................... 4 TAILINGS DUMPING 101....................................................................................................5 OCEAN DUMPING ....................................................................................................................................... 7 RIVER DUMPING........................................................................................................................................... 8 TABLE 3. TAILINGS AND WASTE ROCK DUMPED BY EXISTING MINES EVERY YEAR ......................................... 8 LAKE DUMPING ......................................................................................................................................... 10 CAN WASTES DUMPED IN BODIES OF WATER BE CLEANED UP? ................................................................ 10 CASE STUDIES: BODIES OF WATER MOST THREATENED BY DUMPING .................................11 LOWER SLATE LAKE, FRYING PAN LAKE ALASKA, USA .................................................................................. 12 NORWEGIAN FJORDS ...............................................................................................................................