Sea Level Rise Adaption Strategies.Pub

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Campground East of Highway

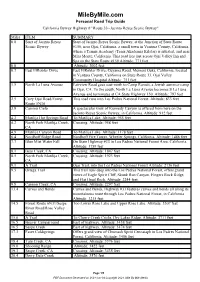

MileByMile.com Personal Road Trip Guide California Byway Highway # "Route 33--Jacinto Reyes Scenic Byway" Miles ITEM SUMMARY 0.0 Start of Jacinto Reyes Start of Jacinto Reyes Scenic Byway, at the Junction of State Route Scenic Byway #150, near Ojai, California, a small town in Ventura County, California, where a Tennis Academy (Tenis Akademia Kilatas) is situated, and near Mira Monte, California. This road lies just across Ojai Valley Inn and Spa on the State Route #150 Altitude: 771 feet 0.0 Altitude: 3002 feet 0.7 East ElRoblar Drive East ElRoblar Drive, Cuyama Road, Meiners Oaks, California, located in Ventura County, California on State Route 33, Ojai Valley Community Hospital Altitude: 751 feet 1.5 North La Luna Avenue Fairview Road goes east-north to Camp Ramah, a Jewish summer camp in Ojai, CA. To the south, North La Luna Avenue becomes S La Luna Avenue and terminates at CA State Highway 150. Altitude: 797 feet 2.5 Cozy Ojai Road/Forest This road runs into Los Padres National Forest. Altitude: 833 feet Route 5N34 3.9 Camino Cielo A spectacular view of Kennedy Canyon is offered from here on the Jacinto Reyes Scenic Byway, in California. Altitude: 912 feet 4.2 Matilija Hot Springs Road To Matilija Lake. Altitude: 955 feet 4.2 North Fork Matilija Creek, Crossing. Altitude: 958 feet CA 4.9 Matilija Canyon Road To Matilija Lake. Altitude: 1178 feet 6.4 Nordhoff Ridge Road Nordhoff Fire Tower, Wheeler Springs, California. Altitude: 1486 feet 7.7 Blue Mist Water Fall On State Highway #33 in Los Padres National Forest Area, California. -

To Oral History

100 E. Main St. [email protected] Ventura, CA 93001 (805) 653-0323 x 320 QUARTERLY JOURNAL SUBJECT INDEX About the Index The index to Quarterly subjects represents journals published from 1955 to 2000. Fully capitalized access terms are from Library of Congress Subject Headings. For further information, contact the Librarian. Subject to availability, some back issues of the Quarterly may be ordered by contacting the Museum Store: 805-653-0323 x 316. A AB 218 (Assembly Bill 218), 17/3:1-29, 21 ill.; 30/4:8 AB 442 (Assembly Bill 442), 17/1:2-15 Abadie, (Señor) Domingo, 1/4:3, 8n3; 17/2:ABA Abadie, William, 17/2:ABA Abbott, Perry, 8/2:23 Abella, (Fray) Ramon, 22/2:7 Ablett, Charles E., 10/3:4; 25/1:5 Absco see RAILROADS, Stations Abplanalp, Edward "Ed," 4/2:17; 23/4:49 ill. Abraham, J., 23/4:13 Abu, 10/1:21-23, 24; 26/2:21 Adams, (rented from Juan Camarillo, 1911), 14/1:48 Adams, (Dr.), 4/3:17, 19 Adams, Alpha, 4/1:12, 13 ph. Adams, Asa, 21/3:49; 21/4:2 map Adams, (Mrs.) Asa (Siren), 21/3:49 Adams Canyon, 1/3:16, 5/3:11, 18-20; 17/2:ADA Adams, Eber, 21/3:49 Adams, (Mrs.) Eber (Freelove), 21/3:49 Adams, George F., 9/4:13, 14 Adams, J. H., 4/3:9, 11 Adams, Joachim, 26/1:13 Adams, (Mrs.) Mable Langevin, 14/1:1, 4 ph., 5 Adams, Olen, 29/3:25 Adams, W. G., 22/3:24 Adams, (Mrs.) W. -

Local Venturan Awarded Third Highest DOD Medal

Does Ventura have enough water? Pages 2&10 Vol. Vol. 3, 12, No. No. 11 14 Published Every Other Published Wednesday Every Other Established Wednesday 2007 April 10 – April March 23, 2019 10 - 23, 2010 “I like seeing results and I like to make people happy whenever possible.” Jim Friedman’s Madhu Bajaj and Dr. Rice enjoyed the talents of Serena Ropersmith, Kelsa Ropersmith and Kamille Kada. new perspective Dennis Cam Kelsch received medal for on serving the 18th Annual Festival of Talent gallantry against an armed enemy. by Amy Brown Local Ventura people Talent is one of the Ventura Unified Beat”, on March 23rd. The show featured School District’s natural resources, as a range of dynamic performances, from by Maryssa Rillo evidenced by this year’s much anticipat- a big production opening act featuring Venturan Jim Friedman served as a member ed Festival of Talent event, “We Got The Continued on page 24 of the Ventura City Council from 1995- awarded third 2002. He also served as mayor in 1998 and 1999. Now, 15 years later, Friedman is back and was reelected in 2018 to highest DOD represent District 5. According to Friedman, money is a Medal bigger issue today than it was the first Ventura native, and 2008 graduate time he served. The break he had from of Ventura High School was presented a serving on the Ventura City Council Silver Star Medal during a ceremony at gave him the opportunity to gain a new the Mighty Eighth Air Force Museum, perspective of the city and see what was Pooler, Georgia on April 9. -

Coastal Area Plan

VENTURA COUNTY GENERAL PLAN COASTAL AREA PLAN Last Amended 9-16-08 Ventura County Planning Division Acknowledgements 1978-1982 Ventura County Board of Supervisors David E. Eaton First District Edwin A. Jones Second District J. K. (Ken) MacDonald Third District James R. Dougherty Fourth District Thomas E. Laubacher, Chairman Fifth District Ventura County Planning Commission Vinette Larson First District Earl Meek Second District Glenn Zogg Third District Curran Cummings, Chairman Fourth District Bernice Lorenzi Fifth District Resource Management Agency Victor R. Husbands, Director Planning Division Dennis T. Davis Manager Kim Hocking, Supervisor, Advanced Planning Jeff Walker, Project Manager Trish Davey, Assistant Planner Jean Melvin, Assistant Planner Kheryn Klubnikin, Assistant Planner This Plan was prepared with financial assistance from the Office of Coastal Zone Management, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, under provisions of the Federal Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972. For Copies/More Info: To purchase the Ventura County Coastal Area Plan: Call 805/654-2805 or go to the Resource Management Agency receptionist 3rd floor of the Government Center Hall of Administration 800 S. Victoria Avenue, Ventura, CA This Coastal Area Plan is also available on our website: http://www.ventura.org/planning VENTURA COUNTY GENERAL PLAN COASTAL AREA PLAN Ventura County Board of Supervisors California Coastal Commission California Coastal Act of 1976 adopted Plan Adopted - November 18, 1980 California Coastal Act amended, effective January, 1981 Amended - April 14, 1981 Conditionally Certified -August 20, 1981 Amended - March 30, 1982 Certified - June 18, 1982 Amended - October 15, 1985 Certified - February 7, 1986 Amended - December 20, 1988 Certified - May 10, 1989 Amended - June 20, 1989 Certified - October 10 & 12, 1989 Amended - December 11, 1990 Certified - March 15, 1991 Amended - October 19, 1993 Certified - February 16, 1994 Amended - December 10, 1996 Certified - April 10, 1997 Amended - Dec. -

Section 9813 – Ventura County

Section 9813 – Ventura County 9813 Ventura County (GRA 7)………………………………………………………………………………………. 473 9813.1 Response Summary Tables……………………………………………………………………….. 474 9813.2 Geographic Response Strategies for Environmental Sensitive Sites……………. 478 9813.2.1 GRA 7 Site Index……………………………………………………………………………….. 479 9813.3 Economic Sensitive Sites……………………………………………………………………………. 526 9813.4 Shoreline Operational Divisions………………………………………………………………….. 531 9813 Ventura County (GRA 7) Ventura County GRA 7 begins at the border with Santa Barbara County and extends southeast approximately 40 miles to the border with Los Angeles County. There are thirteen Environmental Sensitive Sites. Most of the shoreline is fine to medium grain sandy beach and rip rap. There are several coastal estuaries and wetlands of varying size with the largest being Mugu Lagoon. Most of the shoreline is exposed except for two large private boat harbors and a commercial/Navy port. LA/LB - ACPs 4/5 473 v. 2019.2 - June 2021 9813.1 Response Summary Tables A summary of the response resources is listed by site and sub-strategy next. LA/LB - ACPs 4/5 474 v. 2019.2 - June 2021 Summary of ACP 4 GRA 7 Response Resources by Site and Sub-Strategy Site Site Name Sub- PREVENTION OBJECTIVE OR CONDITION FOR DEPLOYMENT Strategy Equipment Sub-Type Size/Unit QTY/Unit 4-701 Rincon Creek and Point .1 - Exclude Oil Boom Swamp Boom 200 feet Boom Sorbent Boom 200 feet Vehicle ATV 1 Staff 4 Anchor 8 .2 - Erect Filter Fence Misc. Oil Snare (pom-pom) 600 Misc. Stake Driver 1 Vehicle ATV 1 Fence Construction Fencing 4 x 100 feet 2 Rolls Stakes T-posts 6 feet 20 Staff 4 .3 - Shoreline Pre-Clean: Resource Specialist Supervision Required Staff 5 Vehicle ATV 1 Misc. -

California State Parks Western Snowy Plover Management 2009 System-Wide Summary Report

California State Parks Western Snowy Plover Management 2009 System-wide Summary Report In 1993, the coastal population of western snowy plover (WSP) in California, Washington and Oregon was listed as a threatened species under the Federal Endangered Species Act due to habitat loss and disturbance throughout its coastal breeding range. In 2001, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife (USFWS) released a draft WSP recovery plan that identified important management actions needed to restore WSP populations to sustainable levels. Since California State Parks manages about 28% of California’s coastline and a significant portion of WSP nesting habitat, many of the actions called for were pertinent to state park lands. Many of the management recommendations were directed at reducing visitor impacts since visitor beach use overlaps with WSP nesting season (March to September). In 2002, California State Parks developed a comprehensive set of WSP management guidelines for state park lands based on the information contained in the draft recovery plan. That same year a special directive was issued by State Park management mandating the implementation of the most important action items which focused on nest area protection (such as symbolic fencing), nest monitoring, and public education to increase visitor awareness and compliance to regulations that protect plover and their nesting habitat. In 2007 USFWS completed its Final Recovery Plan for the WSP; no new management implications for State Parks. This 2009 State Parks System-wide Summary Report summarizes management actions taken during the 2009 calendar year and results from nest monitoring. This information was obtained from the individual annual area reports prepared by State Park districts offices and by the Point Reyes Bird Observatory - Conservation Science (for Monterey Bay and Oceano Dunes State Vehicular Recreation Area). -

National List of Beaches 2004 (PDF)

National List of Beaches March 2004 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Office of Water 1200 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington DC 20460 EPA-823-R-04-004 i Contents Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 1 States Alabama ............................................................................................................... 3 Alaska................................................................................................................... 6 California .............................................................................................................. 9 Connecticut .......................................................................................................... 17 Delaware .............................................................................................................. 21 Florida .................................................................................................................. 22 Georgia................................................................................................................. 36 Hawaii................................................................................................................... 38 Illinois ................................................................................................................... 45 Indiana.................................................................................................................. 47 Louisiana -

Looking Back at 2018, Page 2 Ventura Music Festival 25Th Season Expands

Looking back at 2018, page 2 Vol. Vol. 3, 12, No. No. 11 7 Published Every Other Published Wednesday Every Other Established Wednesday 2007 January 3 – January March 15, 102019 - 23, 2010 Newly appointed Mayor Matt LaVere spoke during the event, recalled watching the devastation and wondering how the city could ever recover from the catastrophic event that leveled over 500 homes in Ventura. LaVere said, “But we sat down that next week and we were talking about the idea of Ventura strong and the amazing strength and resiliency of this community. We said our number one priority in 2018 has to get homes rebuilt and back into their homes. And here we are one year later, celebrating the first two homeowners who have rebuilt and are moving back into their homes and I think that is a momentous occasion.” Ribbon cutting for first two homes Ed Fuller is an avid singer and was at a rehearsal for his barbershop quartet in Camarillo when news of the spreading Helen always remained glamorous. rebuilt after the Thomas Fire Thomas Fire reached him. Fuller raced by Richard Lieberman back to his Ventura home, but like 500 VCF receives Ed and Sandy Fuller celebrated the Ventura city officials was held in front other Ventura families, his home would completion of their home rebuild after of the new home and another across the be destroyed. donation from the Thomas fire devastated their neigh- street at the newly completed residence On the morning of the ribbon borhood and reduced their beloved home of Michael and Sandra Gustafson who cutting ceremony, Ed and his barber Helen Yunker to ashes. -

Western Snowy Plover Annual Report 2015 Channel Coast District

Western snowy plover nest inside of a lobster trap. Photo by: Debra Barringer taken at McGrath State Beach 2015 Western Snowy Plover Annual Report 2015 Channel Coast District By Alexis Frangis, Environmental Scientist Nat Cox, Senior Environmental Scientist Federal Fish and Wildlife Permit TE-31406A-1 State Scientific Collecting Permit SC-010923 Channel Coast District 2015 Western Snowy Plover Annual Report Goals and Objectives ................................................................................................................ 3 Ongoing Objectives:................................................................................................................ 3 2014-2015 Management Strategies ......................................................................................... 4 Program Overview and Milestones ......................................................................................... 4 METHODS .............................................................................................................................. 6 Monitoring .............................................................................................................................. 10 MANAGEMENT ACTIONS ............................................................................................... 12 Superintendent’s Closure Order ............................................................................................ 12 Nesting Habitat Protective Fencing ..................................................................................... -

Campings Californië

Campings Californië Angels Camp - Angels Camp RV & Camping Resort Anza-Borrego Desert State Park - Anza-Borrego Desert State Park - Palm Canyon Hotel & RV Resort - The Springs at Borrego RV Resort Bakersfield Cloverdale - River Run RV Park - Cloverdale/Healdsburg KOA - Orange Grove RV Park - Bakersfield RV Resort Coleville - A Country RV Park - Coleville/ Walker KOA - Bakersfield RV Travel Park - Shady Haven RV Park Crescent City, Jedediah Smits Redwood SP - Kern River Campground - Crescent City / Redwoods KOA Holiday - Jedediah Smith Campground Banning - Redwood Meadows RV Resort - Banning Statecoach KOA - Ramblin' Redwoods Campground and RV Barstow Cuyamaca Rancho State Park / Descanso - Barstow/Calico KOA - Paso Picacho Campground - Green Valley Campground - Shady Lane RV Camp - Calico Ghost Town campground Death Valley NP Blythe - Fiddlers Campground - The Cove Colorado River RV resort - Furnace Creek (NPS Campground) - Hidden Beachers Resort - Stovepipe Wells RV Park - Stovepipe Wells (NPS Campground) Bodega Bay - Sunset Campground - Porto Bodega Marina and RV Park - Mesquite Springs Campground - Bodega Bay RV Park - Shoshone RV Park Let op! Tussen juni t/m sept staan de meeste verhuurders Boulevard het niet toe dat je door Death Valley rijdt. - Boulevard/Cleveland National Forest KOA Eureka Buellton (Highway 1) - Shoreline RV Park - Flying Flags RV Resort & Campground - Mad River Rapids RV Park Carlsbad Fresno - South Carlsbad State Beach Campground - Fort Washington Beach Campground - Paradise by the Sea RV Resort - Blackstone -

River Parkway the Ventura

To Upper Ventura River Parkway Coyote Creek & Ojai Valley Trail 33 150 33 Casitas Vista Rd Foster Park Trailhead rve Mile 6.5 se e r p P H k O c T O : o r V Foster Park e n t g u i r a R b i v e r P a r k w a y V i s i o Upper n P l a n , 2 0 0 Big Rock Preserve Mile 6 9 FIGURE ii The Lower Ventura River, looking south from its confl uence with the Canada Larga. 101 Lower PARKWAY LOWER Big Rock Preserve 33 guide to the lower N Ventura Ave Avenue Water ventura river parkway Ojai Valley Treatment Sanitation Plant Plant Canada Larga Creek The Ventura River Parkway is a network of parks, open space, and trails that provide opportunities for recreation, education and stewardship of the Ventura River. the The Ventura River Trail (1999) and the Ojai Valley Trail (1983) provide a continuous v San Buenaventura Canada en multi-use paved path along the Ventura River corridor from the beach all the tu Mission Aqueduct Larga Rd r a Spring St way to the City of Ojai. The trail follows the route of the old Southern r iv Pacific Railroad that once transported Ojai Valley produce to Ventura. e r The 1969 floods washed out much of the tracks, which were later w Brooks Institute of Photography converted from ‘Rails to Trails’. Many side trips provide access to the a t river and creeks as well as scenic overviews of the watershed. -

Beach Wheelchairs Available to Loan for Free

Many sites along the California coast have beach wheelchairs available to loan for free. Typically reservations are not taken; it’s first come-first served. Times and days when they are available vary from site to site. This list was last updated in 2012. We've included the name of the beach/park, contact phone number, and if a motorized beach wheelchair is available in addition to a manual chair. San Diego County Imperial Beach, (619) 685-7972, (motorized) Silver Strand State Beach, (619) 435-0126, (motorized) Coronado City Beach, (619) 522-7346, (motorized) Ocean Beach, San Diego, (619) 525-8247 Mission Beach, San Diego (619) 525-8247, (motorized) La Jolla Shores Beach, South pacific Beach, (619) 525-8247 Torrey Pines State Beach, (858) 755-1275 Del Mar City Beach, (858) 755-1556 San Elijo State Beach, (760) 633-2750 Moonlight Beach, (760) 633-2750 South Carlsbad State Beach, (760) 438-3143 Oceanside City Beach, (760) 435-4018 San Onofre State Beach, (949) 366-8593 Orange County San Clemente City Beach, (949) 361-8219 Doheny State Beach, (949) 496-6172 Salt Creek Beach Park, (949) 276-5050 Aliso Beach, (949) 276-5050 Main Beach, (949) 494-6572 Crystal Cove State Park, (949) 494-3539 Corona del Mar State Beach, (949) 644-3047 Balboa Beach, (949) 644-3047 1 Newport Beach, (949) 644-3047 Huntington State Beach, (714) 536 1454 Huntington City Beach, (714) 536-8083 Bolsa Chica State Beach, (714) 377-5691 Seal Beach, (562) 430-2613 Los Angeles County Cabrillo Beach, (310) 548-7567 Torrance County Beach, (310) 372-2162 Hermosa City Beach, (310)