Protection Monitoring Task Force

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Education in Danger

Education in Danger Monthly News Brief December Attacks on education 2019 The section aligns with the definition of attacks on education used by the Global Coalition to Protect Education under Attack (GCPEA) in Education under Attack 2018. Africa This monthly digest compiles reported incidents of Burkina Faso threatened or actual violence 10 December 2019: In Bonou village, Sourou province, suspected affecting education. Katiba Macina (JNIM) militants allegedly attacked a lower secondary school, assaulted a guard and ransacked the office of the college It is prepared by Insecurity director. Source: AIB and Infowakat Insight from information available in open sources. 11 December 2019: Tangaye village, Yatenga province, unidentified The listed reports have not been gunmen allegedly entered an unnamed high school and destroyed independently verified and do equipment. The local town hall was also destroyed in the attack. Source: not represent the totality of Infowakat events that affected the provision of education over the Cameroon reporting period. 08 December 2019: In Bamenda city, Mezam department, Nord-Ouest region, unidentified armed actors allegedly abducted around ten Access data from the Education students while en route to their campus. On 10 December, the in Danger Monthly News Brief on HDX Insecurity Insight. perpetrators released a video stating the students would be freed but that it was a final warning to those who continue to attend school. Visit our website to download Source: 237actu and Journal Du Cameroun previous Monthly News Briefs. Mali Join our mailing list to receive 05 December 2019: Near Ansongo town, Gao region, unidentified all the latest news and resources gunmen reportedly the director of the teaching academy in Gao was from Insecurity Insight. -

Idleb Governorate, Ariha District April 2018

Humanitarian Situation Overview in Syria (HSOS): Sub-district Factsheets Idleb GovernorateGovernorate, Ariha District JanuaryApril 2018 Introduction This multi-sectoral needs assessment is part of a monthly data collection exercise which aims to gather information about needs and the humanitarian situation inside Syria. The factsheets present information collected in MayFebruary 2018, 2018, referring referring to the to situation the situation in April in ALEPPO January2018. 2018. These factsheets present information at the community level for 21three sub-districts sub-districts in in Idleb Ariha governorate.district in Idleb Selected governorate. key indicatorsSelected keyfor IDLEB theindicators following for sectorsthe following are included sectors inare the included factsheets: in the displacement, factsheets: shelter,displacement, non-food shelter, items non-food(NFIs), health, items food(NFIs), security, health, water food sanitation security, andwater hygiene sanitation (WASH) and hygiene and education. (WASH) The and factsheets education. do The not factsheets cover the Mhambal Ariha entiredo not rangecover theof indicators entire range gathered of indicators in the gathered questionnaire. in the questionnaire. Ehsem For full visualisation of all indicators collected, please see the SIMAWG Needs Identification Dynamic Reporting Tool, available here: http://www.reach-info.org/syr/simawg/.https://reach3.cern.ch/simawg/Default.aspx. LATTAKIA Methodology and limitations HAMA These findings areare basedbased onon datadata collected collected both directly directly (in andTurkey) remotely from (inKey Turkey) Informants from (KIs)Key Informants residing in residing the communities in the communities assessed. assessed. Information waswas collectedcollected from from KIs Key in 60Informants communities in 143 in 3communities sub districts inof 21Idleb sub-districts governorate. of IdlebFor eachgovernorate. -

The Aid in Danger Monthly News Brief – June 2019 Page 1 Ngos of Demanding Bribes from Them for Their Repatriation to Somalia and Other Services

Aid in Danger Monthly News Brief June 2019 This monthly digest Safety, security and access incidents comprises threats and Insecurity affecting aid workers and aid delivery incidents of violence affecting the delivery of Africa humanitarian assistance. Cameroon Throughout June 2019: In unspecified Anglophone locations, armed separatists set fire to an unspecified number of shipments of food, It is prepared by medicine and bedding escorted by the Cameroon Armed Forces, Insecurity Insight from claiming that they will never accept aid from the Cameroonian information available in Government. Source: VOA open sources. Central African Republic 25 June 2019: In Batangafo, Ouham prefecture, an INGO national aid All decisions made, on the worker was reportedly assaulted in a home invasion by armed anti- basis of, or with Balaka militants. Four other occupants were robbed of their mobile consideration to, such phones, cash, and other items. The aid worker received medical information remains the treatment, and the perpetrators were handed over to MINUSCA by a responsibility of their local anti-Balaka leader. Source: AWSD1 respective organisations. Democratic Republic of the Congo 05 June 2019: In Lubero, North Kivu, suspected Mai-Mai militants Subscribe here to receive kidnapped two NGO workers. No further details specified. Source: monthly reports on ACLED2 insecurity affecting the delivery of aid. 25 June 2019: In North Kivu, Katwiguru II, an unidentified armed group kidnapped an aid worker from the INGO Caritas. No further details specified. Source: ACLED2 Visit our website to download previous Aid in Eritrea Danger Monthly News Throughout June 2019: The Eritrean Government continued to deny Briefs. the Human Rights Council’s Special Rapporteur on Human Rights in Eritrea access to Eritrea. -

Health Cluster Bulletin

HEALTH CLUSTER BULLETIN April 2020 Fig.: Disinfection of an IDP camp as a preventive measure to ongoing COVID-19 Turkey Cross Border Pandemic Crisis (Source: UOSSM newsletter April 2020) Emergency type: complex emergency Reporting period: 01.04.2020 to30.04.2020 12 MILLION* 2.8 MILLION 3.7 MILLION 13**ATTACKS PEOPLE IN NEED OF HEALTH PIN IN SYRIAN REFUGGES AGAINST HEALTH CARE HEALTH ASSISTANCE NWS HNO 2020 IN TURKEY (**JAN - APR 2020) (A* figures are for the Whole of Syria HNO 2020 (All figures are for the Whole of Syria) HIGHLIGHTS • During April, 135,000 people who were displaced 129 HEALTH CLUSTER MEMBERS since December went back to areas in Idleb and 38 IMPLEMENTING PARTNERS REPORTING 1 western Aleppo governorates from which they MEDICINES DELIVERED TREATMENT COURSES FOR COMMON were displaced. This includes some 114,000 people 281,310 DISEASES who returned to their areas of origin and some FUNCTIONAL HEALTH FACILITIES HERAMS 21,000 IDPs who returned to their areas of origin, FUNCTIONING FIXED PRIMARY HEALTH forcing partners to re-establish health services in 141 CARE FACILITIES some cases with limited human resources. 59 FUNCTIONING HOSPITALS • World Health Day (7 April 2020) was the day to 72 MOBILE CLINICS celebrate the work of nurses and midwives and HEALTH SERVICES2 remind world leaders of the critical role they play 750,416 CONSULTATIONS in keeping the world healthy. Nurses and other DELIVERIES ASSISTED BY A SKILLED health workers are at the forefront of COVID-19 10,127 ATTENDANT response - providing high quality, respectful 8,530 REFERRALS treatment and care. Quite simply, without nurses, 822,930 MEDICAL PROCEDURES there would be no response. -

Health Cluster Bulletin, May 2018 Pdf, 1.17Mb

HEALTH CLUSTER BULLETIN Gaziantep, May 2018 A man inspects a damaged hospital after air strikes in Eastern Ghouta. Source: SRD Turkey Cross Border Emergency type: complex emergency Reporting period: 01.05.2018 to 31.05.2018 11.3 MILLION 6.6 MILLION 3.58 MILLION 111 ATTACKS IN NEED OF INTERNALLY SYRIAN REFUGEES AGAINST HEALTH CARE HEALTH ASSISTANCE DISPLACED IN TURKEY (JAN-MAY 2018) (All figures are for the Whole of Syria) HIGHLIGHTS HEALTH CLUSTER Mentor Initiative treated 33,000 cases of 96 HEALTH PARTNERS & OBSERVERS Cutaneous Leishmaniasis and 52 cases of 1 Visceral Leishmaniasis in 2017 through 135 MEDICINES DELIVERED health facilities throughout Syria. TREATMENT COURSES FOR COMMON 369,170 DISEASES The Health Cluster’s main finds from multi- FUNCTIONAL HEALTH FACILITIES sectoral Rapid Needs Assessment which FUNCTIONING FIXED PRIMARY covered 180 communities (out of 220) from 166 HEALTH CARE FACILITIES seven sub-districts in Afrin from 3 to 8 May indicates limited availability of health facilities 82 FUNCTIONING HOSPITALS and medical staff, lack of transportation and 70 MOBILE CLINICS the lack of medicines and specialized services. HEALTH SERVICES The medical referral mechanism implemented 1 M CONSULTATIONS in Idleb governorate includes 48 facilities and 10,210 DELIVERIES ASSISTED BY A SKILLED 14 NGO partners that will be fully operational ATTENDANT as a network by end of August. The network, 8,342 REFERRALS which also includes 9 secondary health care VACCINATION facilities, in total serves a catchment 2 population of 920,000 people. In May 2018, 29,646 CHILDREN AGED ˂5 VACCINATED these facilities produced 1,469 referrals. DISEASE SURVEILLANCE In northern Syria as of end of May, there are 495 SENTINEL SITES REPORTING OUT OF 77 health facilities that are providing MHPSS A TOTAL OF 500 services, including the active mhGAP doctors FUNDING $US3 who are providing mental health 63 RECEIVED 14.3% 85.7% GAP consultations. -

The Turkish War on Afrin Jeopardizes Progress Made Since the Liberation of Raqqa April 2018

Viewpoints No. 125 The Turkish War on Afrin Jeopardizes Progress Made Since the Liberation of Raqqa April 2018 Amy Austin Holmes Middle East Fellow Wilson Center Turkey’s assault on Afrin represents a three-fold threat to the civilian population, the model of local self-governance, and the campaign to defeat the Islamic State. None of this is in the interest of the United States. ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ The Turkish operation in Afrin is not just another battle in a small corner of Syria, but represents a new stage in the Syrian civil war and anti-ISIS campaign. President Erdoğan’s two-month battle to capture Afrin signals that Turkey will no longer act through proxies, but is willing to intervene directly on Syrian territory to crush the Kurdish YPG forces and the experiment in self-rule they are defending.i Emboldened after claiming victory in Afrin, and enabled by Russia, Erdoğan is threatening further incursions into Syria and Iraq. Erdoğan has demanded that American troops withdraw from Manbij, so that he can attack the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) who are stationed in the area, and who have been our most reliable partners in the anti-ISIS coalition. If Erdoğan is not deterred, much of the progress made since the liberation of Raqqa could be in jeopardy. The Afrin intervention has already displaced at least 150,000 people. Many of them are Kurds, Yezidis, or Christians who established local government councils in the absence of the regime over the past five years. Even if imperfect, the self-administration is an embryonic form of democracy that includes women and minorities while promoting religious tolerance and linguistic diversity. -

In Idleb & Hama

وﺣﺪة ﺗﻨﺴﯿﻖ اﻟﺪﻋﻢ ASSISTANCE COORDINATION UNIT Flash Report Field Developments and Displacement Movements in Idleb & Hama Edition 03 May 2019 Issued by Information Management Unit First Field situation in Idleb Governorate and the Adjacent Countrysides Idleb is considered to be the only governorate that is fully under the opposition's control. The opposition factions control the city of Idleb, the centre of the governorate, as well as all the cities and towns of the governorate, except for some towns situated in the southern and eastern Idleb countrysides. The opposition factions also control the areas of Madiq castle, Ziyara and Kafr Zeita in the northern countryside of Hama governorate. The Syrian regime is trying with the support of its international allies to impose control over the governorate of Idleb; so, it escalated its military operations and continued shelling the governorates of Idleb and Hama until SOCHI agreement was reached by Turkey and Russia. This agreement aimed to establish a demilitarized zone in the governorate of Idleb and adjacent countrysides of Aleppo and Hama. The agreement required setting up a 15-20 km demilitarized zone along the contact line between the Syrian regime troops and opposition forces in Idleb, Hama, and Aleppo governorates. Turkey, which guarantees the commitment of the opposition forces to the agreement, deployed its observation posts in opposition-held areas. Likewise, Russian forces stepped up their deployment in the buffer zone within the territory under the control of the regime forces, as the guarantor of the regime’s commitment to the implementation of the agreement. The Syrian regime continued violating the agreement by targeting the demilitarized areas on a daily basis resulting in the death and injuries of the civilians. -

Syrie : Situation De La Population Yézidie Dans La Région D'afrin

Syrie : situation de la population yézidie dans la région d’Afrin Recherche rapide de l’analyse-pays Berne, le 9 mai 2018 Impressum Editeur Organisation suisse d’aide aux réfugiés OSAR Case postale, 3001 Berne Tél. 031 370 75 75 Fax 031 370 75 00 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: www.osar.ch CCP dons: 10-10000-5 Versions Allemand et français COPYRIGHT © 2018 Organisation suisse d’aide aux réfugiés OSAR, Berne Copies et impressions autorisées sous réserve de la mention de la source. 1 Introduction Le présent document a été rédigé par l’analyse-pays de l’Organisation suisse d’aide aux ré- fugiés (OSAR) à la suite d’une demande qui lui a été adressée. Il se penche sur la question suivante : 1. Quelle est la situation actuelle des Yézidi-e-s dans la région d’Afrin ? Pour répondre à cette question, l’analyse-pays de l’OSAR s’est fondée sur des sources ac- cessibles publiquement et disponibles dans les délais impartis (recherche rapide) ainsi que sur des renseignements d’expert-e-s. 2 Situation de la population yézidie dans la région d’Afrin De 20’000 à 30’000 Yézidi-e-s dans la région d'Afrin. Selon un rapport encore à paraître de la Société pour les peuples menacés (SPM, 2018), quelque 20 000 à 30 000 Yézidis vivent dans la région d'Afrin. Depuis mars 2018, Afrin placée sous le contrôle de la Turquie et des groupes armés alliés à la Turquie. Le 20 janvier 2018, la Turquie a lancé une offensive militaire pour prendre le contrôle du district d'Afrin dans la province d'Alep. -

Operation Euphrates Shield: Implementation and Lessons Learned Lessons and Implementation Shield: Euphrates Operation

REPORT REPORT OPERATION EUPHRATES SHIELD: IMPLEMENTATION OPERATION AND LESSONS LEARNED EUPHRATES MURAT YEŞILTAŞ, MERVE SEREN, NECDET ÖZÇELIK The report presents a one-year assessment of the Operation Eu- SHIELD phrates Shield (OES) launched on August 24, 2016 and concluded on March 31, 2017 and examines Turkey’s future road map against the backdrop of the developments in Syria. IMPLEMENTATION AND In the first section, the report analyzes the security environment that paved the way for OES. In the second section, it scrutinizes the mili- tary and tactical dimensions and the course of the operation, while LESSONS LEARNED in the third section, it concentrates on Turkey’s efforts to establish stability in the territories cleansed of DAESH during and after OES. In the fourth section, the report investigates military and political MURAT YEŞILTAŞ, MERVE SEREN, NECDET ÖZÇELIK lessons that can be learned from OES, while in the fifth section, it draws attention to challenges to Turkey’s strategic preferences and alternatives - particularly in the north of Syria - by concentrating on the course of events after OES. OPERATION EUPHRATES SHIELD: IMPLEMENTATION AND LESSONS LEARNED LESSONS AND IMPLEMENTATION SHIELD: EUPHRATES OPERATION ANKARA • ISTANBUL • WASHINGTON D.C. • KAHIRE OPERATION EUPHRATES SHIELD IMPLEMENTATION AND LESSONS LEARNED COPYRIGHT © 2017 by SETA All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, without permission in writing from the publishers. SETA Publications 97 ISBN: 978-975-2459-39-7 Layout: Erkan Söğüt Print: Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık A.Ş., İstanbul SETA | FOUNDATION FOR POLITICAL, ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL RESEARCH Nenehatun Caddesi No: 66 GOP Çankaya 06700 Ankara TURKEY Tel: +90 312.551 21 00 | Fax :+90 312.551 21 90 www.setav.org | [email protected] | @setavakfi SETA | İstanbul Defterdar Mh. -

Highlights Situation Overview

Syrian Arab Republic: Idleb Situation Report No. 4 (23 April – 6 May 2015) This report is produced by OCHA Syria and Turkey in collaboration with humanitarian partners. It was issued on 11 May. It covers the period from 23 April to 6 May 2015. Highlights The town of Jisr-Ash-Shugur was taken over by NSAGs on April 25, displacing over 40,000 people to surrounding areas. Continued fighting in the area continues to increase humanitarian needs. Aerial bombardment of the central market place in Darkosh town on April 26 reportedly killed 40-50 people, including an NGO staff member, and wounded 100. Two hospitals were reported to be damaged in separate incidents on 2 and 4 May. Incidents of this nature remain frequent and are potential violations of International Humanitarian Law. As of 7 May, according to the CCCM cluster, at least 133,831 people have been displaced by the renewed conflict in Idleb governorate. New reports of attacks leading to death and injuries and allegedly involving chemical agents were received from the field, but could not be independently verified. During the reporting period 1,134 people were reported injured and 36 dead according to local health authorities in Idleb governorate. Consistent reports indicate that many civilians trying to flee to GoS-controlled areas since 20 April have not been allowed to do so, raising protection concerns. Situation Overview The situation in Idleb governorate, particularly in the western district of Jisr-Ash-Shugur and adjacent areas, was highly volatile during the reporting period. On 25 April, non-state armed groups (NSAGs) captured the town of Jisr- Ash-Shugur, resulting in displacement. -

Syria - Displacements from Northern Syria Production Date : 25/08/2016 IDP Locations - As of 16 August 2016

For Humanitarian Purposes Only Syria - Displacements from Northern Syria Production date : 25/08/2016 IDP Locations - As of 16 August 2016 Total number of IDPs: 749,275 BULBUL Raju " RAJU Shamarin Talil Elsham ² Krum Zayzafun - Ekdeh Gender & Age SHARAN Shmarekh Sharan Kafrshush Baraghideh " Tatiyeh Jdideh Maarin Ar-Ra'ee Salama AR-RA'EE " Nayara Ferziyeh A'ZAZ Azaz " Azaz Niddeh 19% MA'BTALI Sijraz Yahmul Maabatli Suran " Jarez " Kafr Kalbein 31% Maraanaz Girls under 18 Al-Malikeyyeh Kaljibrin AGHTRIN Afrin Manaq Akhtrein Boys under 18 " " Sheikh El-Hadid " Mare' Women " A'RIMA Tall Refaat 24% " Men Baselhaya TALL REFAAT AFRIN Deir Jmal MARE' Kafr Naseh Tal Refaat 26% Kafrnaya JANDAIRIS Jandairis " Nabul AL BAB " Al Bab " NABUL Tal Jbine Tadaf " Shelter Type Hayyan T U R K E Y Qah Atma Selwa Random gatherings HARITAN Andan Haritan TADAF Unfinished houses or Daret Azza " " buildings Reyhanli Kafr Bssin Other Qabtan Eljabal Tilaada Individual tents DARET AZZA A L E P P O Babis Deir Hassan - Darhashan Hur Maaret Elartiq Kafr Hamra Rented houses DANA Hezreh - Hezri Termanin Dana Anjara Foziyeh Harim " Bshantara RASM HARAM EL-IMAM Open areas " Tqad Majbineh Aleppo Antakya Ras Elhisn " Total Tlul Kafr Hum Ein Elbikara Aleppo HARIM Tuwama Hoteh Under trees Kafr Mu Tlul Big Hir Jamus QOURQEENA Tal Elkaramej Sahara JEBEL SAMAN Um Elamad Alsafira Besnaya - Bseineh Sarmada Oweijel Htan Tadil Collective center Ariba Qalb Lozeh Barisha Eastern Kwaires " Bozanti Kafr Deryan Kafr Karmin Abzemo Maaret Atarib Allani Radwa Kafr Taal Kafr Naha Home Kafr -

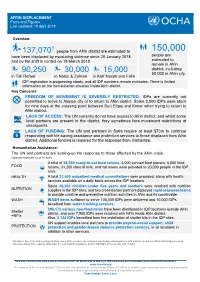

People from Afrin District Are Estimated to Have Been Displaced by Escalating Violence Since 20 January 2018 and by the Shift In

AFRIN DISPLACEMENT Facts and Figures Last updated: 18 April 2018 Overview: 1 137,070 people from Afrin district are estimated to 150,000 have been displaced by escalating violence since 20 January 2018 people are and by the shift in control on 18 March 2018 estimated to remain in Afrin 90,250 30,000 15,000 district, including 50,000 in Afrin city. in Tall Refaat in Nabul & Zahraa in Kafr Naseh and Fafin IDP registration is progressing slowly, and all IDP numbers remain estimates. There is limited information on the humanitarian situation inside Afrin district. Key Concerns: FREEDOM OF MOVEMENT IS SEVERELY RESTRICTED. IDPs are currently not permitted to move to Aleppo city or to return to Afrin district. Some 2,000 IDPs were stuck for nine days at the crossing point between Burj Elqas and Kimar when trying to return to Afrin district. LACK OF ACCESS: The UN currently do not have access to Afrin district, and whilst some local partners are present in the district, they sometimes face movement restrictions at checkpoints. LACK OF FUNDING: The UN and partners in Syria require at least $73m to continue responding with life-saving assistance and protection services to those displaced from Afrin district. Additional funding is required for the response from Gaziantep. Humanitarian Assistance: The UN and partners are scaling-up the response to those affected by the Afrin crisis. [selected highlights as of 16 April] A total of 28,350 ready-to-eat food rations, 3,000 canned food parcels, 5,000 food FOOD rations, 31,200 litres of milk, and hot meals were provided to 20,000 people in the IDP sites.