BRISBANE VALLEY FLYER November- 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Just Do It - Das Tagebuch

1623 Just do it - das Tagebuch Hinweis: das ist ein mehr oder weniger persönliches Tagebuch von mir (Martin), unqualifizierte oder sonstwie kompromittierende Inhalte sind rein subjektiv, entbehren jeder Grundlage und entsprechen in der Regel und meist immer nie der Wirklichkeit. Ähnlichkeiten mit Lebenden und Personen, die scheinbar meinem Bekanntenkreis entstammen, sind, insbesondere wenn sie etwas schlechter wegkommen, nicht beabsichtigt, rein zufällig und ebenfalls in der Regel frei erfunden. Der Leser möge dies bei der Lektüre berücksichtigen und entsprechend korrigierend interpretieren. Auch Schwächen in der Orthografie und der Zeichensetzung seien mir verziehen. Schließlich bewegt sich das Schiff (mehr oder weniger). PS.: Copyright für alle Formen der Vervielfältigung und Weitergabe beim Autor (wo auch sonst). Teil 1441 – 1480 Marsa Alam - Latsi 1.441 (Fr. 10.04.09) Die Nacht war sehr ruhig, aber am Morgen hört man wieder den Wind in den Wanten. Da die gribfiles für heute Nachmittag abnehmenden und für morgen Mittag gar keinen Wind vorhersagen, brechen wir auf. Kaum haben wir die Nase aus der Bucht gesteckt und sind auf den Kurs eingedreht, geht es los. Eine grobe See, Wind von vorn und ganz leichter Schiebestrom. JUST DO IT astet und kämpft, um einen halbwegs vernünftigen Fortschritt zu erzielen. Unser elektrischer Autopilot ist für Spricht für sich die Bedingungen zu schwach, so wird konsequent per Hand gesteuert. Natürlich könnten wir auch mit Hilfe des Windpiloten kreuzen, aber dann bräuchten wir 10.04.09 mindestens doppelt so lange. Wir wollen uns aber nicht so viel Zeit nehmen, denn es Marsa Alam – Port Ghalib sieht so aus, als öffne sich ein Wetterfenster, dass wir noch nutzen könnten. -

Anna Sobol Levy Fellowship Final Report, 2010-11

Anna Sobol Levy Fellowship Final Report, 2010-11 fe"ows Kimberly Seifert Christopher McIntosh Peter Uthe Sarath Ganji Joshua Gotay Nicholas Castle ASL Final Report, 2010-11 1 Biographies Coming from Mosav Ya’ad in northern Israel, Ran Smoly just finished his first year of an honors M.A. program at the Federmann School of Public Policy & Government of Hebrew University. During his military service, Ran was an infantry officer in the Nahal Brigade. He finished is service as a lieutenant and is now a platoon commander of the Border Guard, when called to Reserve duty. He has worked as a tour guide for several companies, mostly guiding youth groups from all over Israel during their educational excursions with school. His military, travel, tour guide experience very much enhance his role as the ASL coordinator. In his opinion, serving in the I.D.F. and living his life under Israel’s high-pressure security situation have given him a hardened knowledge of what ASL fellows should and must learn through this program. Joshua Gotay was a Visiting Student in the Israel Politics and Society programs at Hebrew University's Rothberg International School. He graduated Summa Cum Laude from West Virginia University where he received a bachelors in Political Science with a focus on Law and Legal systems. Additionally, he graduated as a Distinguished Military Graduate and received his commission in May 2010 as an officer in the U.S. Army Medical Service Corps. While in college, Joshua interned in the U.S. Coast Guard's Office of Budget and Programs, and served as an assistant program reviewer. -

De Havilland DH.89 Dragon Rapide

DH.89 DRAGON RAPIDE DH.89 Fitted with 2x200hp Gipsy Six DH.89A Fitted with 2x200hp Gipsy Queen III & small trailing edge flaps under lower wing 6250 (Gipsy Six #6008/6009) Prototype Dragon Six; first flown Hatfield by Hubert Broad 17.4.34 as E.4. (Sale to R Herzig of Ostschweiz AG announced 4.34 for SFr90,000) CofA 4306 issued 10.5.34. CofA renewed 14.7.34 and handed over 16.7.34; deld Altenrhein 18.7.34. Regd CH-287 19.7.34 to Ostschweiz Aero-Gesellschaft, Altenrhein. Regd HB-ARA 1.35 to same owner. Wore Aero St Gallen titles (3.35) for St Gallen/Zurich/Berne service. Damaged in crash 3.35; repaired. Regd 20.3.37 to Swissair AG, Zurich-Dubendorf. Regd HB-APA 6.37 to same owner. To Farner-Werke AG .54 and on overhaul Grenchen (8.54). Reported sale to Spain .54 fell through and regd .55 to Farner Werke AG, Grenchen. Regd .55 to Motorflugruppe Zurich, Aero Club de Suisse, Kloten. Wfu Kloten after final flight 3.10.60. Regn cld 10.5.61. Dumped (62) on Zurich-Kloten airfield and burnt by Zurich Airport Fire Service 8.64. 6251 (Gipsy Six #6014/6015) Regd G-ACPM (CofR 4955) 7.6.34 to Hillman's Airways Ltd, Stapleford. CofA 4365 issued 5.7.34. Entered by Lord Wakefield in King's Cup Air Race 13.7.34, flown by Capt Hubert Broad but withdrawn following hail damage over Waddington. Deld Hillmans 27.7.34. Crashed into English Channel in low cloud 4 mls off Folkestone 2.10.34 inbound from Paris; 7 killed including Capt Walter R Bannister. -

MAR 12.17.Pdf

EDITORIAL TEAM COORDINATING EDITOR - BRIAN PICKERING WESTFIELD LODGE, ASLACKBY, SLEAFORD, LINCS NG34 0HG TEL NO. 01778 440760 E-MAIL [email protected] BRITISH REVIEW - BRIAN PICKERING WESTFIELD LODGE, ASLACKBY, SLEAFORD, LINCS NG34 0HG TEL NO. 01778 440760 E-MAIL [email protected] FOREIGN FORCES - MORAY PICKERING 19 RADFORD MEADOW, CASTLE DONINGTON, DERBY DE74 2NZ E Mail [email protected] US FORCES - BRIAN PICKERING (COORDINATING) (see above for address details) STATESIDE: MORAY PICKERING EUROPE: BRIAN PICKERING OUTSIDE USA: BRIAN PICKERING See address details above OUT OF SERVICE - ANDY MARDEN 6 CAISTOR DRIVE, BRACEBRIDGE HEATH, LINCOLN LN4 2TA E-MAIL [email protected] MEMBERSHIP/DISTRIBUTION - BRIAN PICKERING MAP, WESTFIELD LODGE, ASLACKBY, SLEAFORD, LINCS NG34 0HG TEL NO. 01778 440760 E-MAIL. [email protected] ANNUAL SUBSCRIPTION (Jan-Dec 2018) UK £50 EUROPE £65 ELSEWHERE £70 @MAR £20 (EMail/Internet Only) MAR PDF £20 (EMail/Internet Only) Cheques payable to “B Pickering” or Subscribe via www.militaryaviationreview.com ABBREVIATIONS USED * OVERSHOOT f/n FIRST NOTED l/n LAST NOTED n/n NOT NOTED u/m UNMARKED w/o WRITTEN OFF wfu WITHDRAWN FROM USE n/s NIGHTSTOPPED INFORMATION MAY BE REPRODUCED FROM “MAR” WITH DUE CREDIT EDITORIAL Another year has passed and I hope that you receive the paper magazine before the Christmas break. The January issue will feature the usual UK Review for 2018 (this year it is back in Graeme's capable hands) and the Index for the 2017 issues of MAR. Please remember that if you have to download your 2017 PDF issues for MAR or @MAR that the files will only be on the web site until the end of January and then they will be removed. -

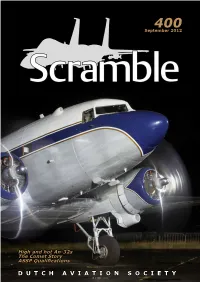

Scramble400 Preview.Pdf

400 September 2012 High and hot An-32s The Comet Story ASSP Qualifications DUTCH AVIATION SOCIETY Alpha Jet E135 has lost its prefix code 213 from Tours and is now only coded -RX. It has been seen previously at Mont de Marsan which is believed to be its new homebase. Jeroen Jonkers saw it on 19 July visiting Orange. The Marine National has two EC225s flying with 32F is the SAR role. When sufficient NH90s are delivered these two EC225s will be trans- ferred to the EH01.067 of the air force. EC225 2752 visited Carcassonne Salvaza on 23 July 2012 where Philippe Devos saw it. With Cambrai being closed as operational base and EC01.012 being disbanded a number of the based Mirage 2000 moved on to Orange. EC01.012 former 121/103-KN is now flying from Orange as 115-KN (26 July 2012, Jeroen Jonkers) Editorial Important dates Currently you are holding yet another historic issue of Scram- Scramble 401 ble in your hands – number 400! We have come a long way Deadline copy: 18 September 2012 from printing a handful of A4s with Amsterdam-Schiphol Deadline photos: 25 September 2012 movements to the Scramble as it is nowadays, packed full of Planned publication date: 9 October 2012 civil and military aviation news. And we won’t stop anytime soon, in fact we continue to expand into the digital age. As of Movements this number we are proud to announce that Scramble is avail- Contents able as a digital magazine too! It features everything that you Movements Netherlands..............................................................2 can read right now, but with all the pictures in colour. -

Bookmarks for Lars Sundin

Bookmarks for Lars Sundin Evreka Böcker, att läsa, personer Air Historic Research In memoriam, flygare i Spanien. Dödannonser och nekrologer. Goodbye nekrologer Famous people who died in aviation accidents Find A Grave Artikelbiblioteket WWII Aviation Booklist: Axis Pilots Biografiskt handlexikon (Svenskt; gammalt) Ulf Björkman Biggles i Sverige Biggles Message Board Biggles, essä Biggles/Snowdonlecornu Biggles Home Page Karin Boye Annas diktsida - andras dikter Lokaler och platser i Bellmans Stockholm Carl Michael Bellman Siten The Roald Dahl Home Page The Roald Dahl Home Page - Books Tage i Media Inspiring Speeches Bob Dylan - songs (alphabetical by title) Elizabeth's Classic Actors Page Site officiel Saint Exupery Enar om Enar Nils Ferlin Ferlin, litet grann av Författarcentrums Läslänkar John F. Graham Hobbybokhandeln AB Konrit-egenföretagarens syn på samhället Björn Kurtén Libération - Portrait Marinlitteratur Marx Brothers Bibliography Bengt von Matern: Munzinger Archiv Myrby Naval Institute Press: Specializing in Military and Naval History and Literature Ramel-texter Gary Page Peter Pohl, författare Gary F Powers Runeberg Project Runeberg 1995 Swedish Front Page (About Project Runeberg) Alphabetic Catalog (Welcome to Project Runeberg) Alexander de Seversky Singalex Song's Homepage Albert Speer Handskrift 68. Chefredaktören vid Allhems förlag Sven Arthur Svenssons, (1910-1982), Bildarkiv. Taube-texter Alan Turing - Home Page WWII Aviation Booklist Kurt Vonnegut Alvar Zacke - Bertil Falk Anders Zorn Åkarps antikvariat, Böcker säljes