Shopping Addiction†

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

6-05 Issue.Qxd

TThhee BBoottttoomm LLiinnee June 2005 A Publication of The Intergroup Association of Debtor's Anonymous Editor’s Notes Opening a Channel to God Hi, Folks, A week after celebrating a year of solven- for work. The stark fact that I alone was cy I lost it by overdrafting my checking responsible for my prosperity and solven- D.A. is the most incredi- account. Overspending had never been cy enraged me. I secretly wished to be ble experience of my my poison, but a propensity to under- carried off to a place where I wouldn’t strange and wonderful earn made me a debtor by default. have to be awake and responsible for my life & it’s miracles keep Truthfully, the overdraft was a relief. In life. Step work with my sponsor shone coming every day! the weeks prior I felt like I was trying to the light on the futility of the situation: I hold up a collapsing ceiling. Losing my needed to go to work and I couldn’t. My My solvent husband and solvency left me no choice but to accept own fear paralyzed me. My easy income I just gave our daughter that this disease is more powerful than enabled me. The situation was hope- the gift of her first year in me. less. My best efforts only made matters a private High School worse. I felt the realization of powerless- and this is a major mira- Last year my life was very different— ness for the first time. Under my own cle of faith. The public money came to me abundantly and steam, I was screwed. -

Signs of Compulsive Spending Do You

Signs of Compulsive Spending Do you ... • Incur unsecured debt to make a purchase? • Go to stores without a list of planned purchases and estimated costs? • Go to stores without knowing what funds are available to pay for the purchase? • Spontaneously purchase items displayed at the checkout stand? • Usually buy something "extra" at the grocery store or gas station? • Make major purchases without researching comparative features and prices? • Make major purchases without considering the long-term financial impact? • Browse mail-order catalogs, the Internet, or stores with no particular purchase in mind? • Watch and buy from a shopping channel? • Shop as one of your recreational activities? • Spend a lot of time thinking and talking about shopping and the great deals you've gotten? • Own multiple numbers of the same thing? • Have a closet full of unworn clothing, shelves of unread books, a storage space filled with unused tools, unused hobby equipment, or other unused items? • Rationalize your purchases because you got it used or on sale? • Buy things for other people when you can't rationalize buying them for yourself? • Spend money to please or impress other people? • Conceal purchases? • Frequently return purchases? • Feel regret, remorse, guilt, or shame after a purchase? • Feel elated after a purchase? • Feel let down after a shopping trip has ended? • Shop to cheer yourself up? • Shop to calm yourself down? • Lack money to pay for basics after purchasing less essential items? • Have a spouse, parent, or child who criticizes, or worries about, your spending? Have you ... • (or your friends) joked about your spending habits? • Neglected basic responsibilities because of time spent shopping? • Stolen items whether or not you had the money to buy them? • Believed that a given purchase would fix some aspect of your life? • Lost a relationship or job because of your spending? If you answered yes to three or more of these signs, you may be a compulsive spender and Debtors Anonymous (D.A.) may be able to help you. -

MARCH 2020 @ Thrive Suffolk

KEY: Weekly Groups New at Thrive Monthly Repeating Special Events 1324 Motor Parkway, Hauppauge, NY 11749 631-822-3396 MARCH 2020 @ Thrive Suffolk Mon-Thurs: 10am-10pm Fri/Sat: 10am-10pm For our most current information/updates, please visit www.ThriveLI.org Sun 10am-5pm KEY: Weekly Groups New at Thrive Monthly Repeating Special Events Bi-Weekly Activities/Events Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Gathering of Fellowship From Anger to Forgiveness- G.Y.S.T. 9:00-10:00am Families Anon 5:30pm Dwyer Project Veteran Peer CODA 1:30PM LICADD Family Support Group 10:00am 12p Men’s Grp-1pm 10am N.A. Meeting 7pm Support Group 12:00pm Movie Night 5pm Debtors Anonymous 11:00am Codependency 12-steps-1pm Trauma to Triumph-5:30p Debtors Anonymous-7pm Design for Living 5:30pm LICADD Bereavement 11:30am Healing Modalities: Crafting 3:00PM Nar-Anon Meeting 7pm A.A. 6:30pm Co-Occurring Disorders Support “Transmuting Challenges” (Wildflowers)- Healing Steps for Vets 1:00pm LICADD Eating Dx. Grp 6pm Refuge Recovery 7:30pm Group 3:30pm 12:15-1:30pm Childhood Abuse 7pm Codependency/12Steps Volunteer Mtg-5pm The Sangha 6:15pm ONE Recovery Meeting 7:30pm Gentle Flow Yoga 2pm *LICADD Anger Mgmt.7:30pm “Getting to Know 8:30pm FIST Family Support Group Soul Notes Guitar Lessons Emotional Sobriety “Step 12” Yourself” 7:30pm 7pm 4:00pm 8pm 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Gathering of Fellowship From Anger to Forgiveness- G.Y.S.T. for Today “Early EAPA BREAKFAST- Dwyer Project Veteran Peer CODA 1:30PM LICADD Family Support Group 10:00am 12p Recovery ” 9:00-10:00am 8:30AM Support Group 12:00pm 10am Debtors Anonymous 11:00am A.A. -

What Are “Twelve-Step” Programs?

What are “Twelve-Step” Programs? Traditional Twelve-Step programs outline a course of action for recovering from an addiction whereby participants proceed through twelve core developmental stages. Twelve-Step programs are a form of self-help in which members of a fellowship struggling with the same problem support each other. The Twelve-Step program originated with Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) (http://aa.org). According to AA, the twelve steps are as follows: (1) We admitted we were powerless over alcohol—that our lives had become unmanageable. (2) Came to believe that a Power greater than ourselves could restore us to sanity. (3) Made a decision to turn our will and our lives over to the care of God as we understood Him. (4) Made a searching and fearless moral inventory of ourselves. (5) Admitted to God, to ourselves, and to another human being the exact nature of our wrongs. (6) Were entirely ready to have God remove all these defects of character. (7) Humbly asked Him to remove our shortcomings. (8) Made a list of all persons we had harmed, and became willing tomake amends to them all. (9) Made direct amends to such people wherever possible, except when to do so would injure them or others. (10) Continued to take personal inventory and when we were wrong promptly admitted it. (11) Sought through prayer and meditation to improve our conscious contact with God, as we understood Him, praying only for knowledge of His will for us and the power to carry that out. (12) Having had a spiritual awakening as the result of these Steps, we tried to carry this message to alcoholics, and to practice these principles in all our affairs. -

Process Addictions

Defining, Identifying and Treating Process Addictions PRESENTED BY SUSAN L. ANDERSON, LMHC, NCC, CSAT - C Definitions Process addictions – a group of disorders that are characterized by an inability to resist the urge to engage in a particular activity. Behavioral addiction is a form of addiction that involves a compulsion to repeatedly perform a rewarding non-drug-related behavior – sometimes called a natural reward – despite any negative consequences to the person's physical, mental, social, and/or financial well-being. Behavior persisting in spite of these consequences can be taken as a sign of addiction. Stein, D.J., Hollander, E., Rothbaum, B.O. (2009). Textbook of Anxiety Disorders. American Psychiatric Publishers. American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) As of 2011 ASAM recognizes process addictions in its formal addiction definition: Addiction is a primary, chronic disease of pain reward, motivation, memory, and related circuitry. Dysfunction in these circuits leads to characteristic biological, psychological, social, and spiritual manifestations. This is reflected in an individual pathologically pursuing reward and/or relief by substance use and other behaviors. Addictive Personality? An addictive personality may be defined as a psychological setback that makes a person more susceptible to addictions. This can include anything from drug and alcohol abuse to pornography addiction, gambling addiction, Internet addiction, addiction to video games, overeating, exercise addiction, workaholism and even relationships with others (Mason, 2009). Experts describe the spectrum of behaviors designated as addictive in terms of five interrelated concepts which include: patterns habits compulsions impulse control disorders physiological addiction Such a person may switch from one addiction to another, or even sustain multiple overlapping addictions at different times (Holtzman, 2012). -

Debtors Anonymous and Health Issues

p. 1 Debtors Anonymous and Health Issues 2 – For Mental and Physical issues, particularly but not exclusively focusing on recovery for compulsive debtors affected by abuse and trauma, neglect and dysfunction in early life. Meeting Format Thursdays 1pm - 2 pm EST Phone number: 1- 515-739-1423 Leader and All Members Use Access Code: 408137# Per DATIG’s instruction: Leader Code is not posted online. Please contact your group. Once we have figured the new prompts, we can type them into these instructions. Ie: 1. *6 mutes / this is the same as before 2. *5 leader mutes callers 3. There is a Q and A mode that is an advanced form of communication = *1 4. How to turn chimes off: *8 (funnel through until it says all turned off) 5. Number of callers: *2 6. Is this meeting an hour and 15 minutes? Biz Mtg is stated to be. The regular meeting used to be be. Recently we’ve been doing only an hour. 7. Everyone calls in unmuted: this was for the old call, this needs to be checked. 8. I am not clear about the topics for Week #2. It’s below. Today I was told we only do the steps, but it says steps, traditions and concepts. Do we need to have this wording adjusted? Note to chairperson: Please read through prior to chairing the meeting so you can be familiarized with the instructions. Meeting Script WHEN YOU FIRST COME ON THE LINE AS LEADER Please press *8 till you hear “Entry and exit chimes are off” and *5 to mute the line I. -

Gambling Addiction: an Introduction for Behavioral Health Providers

ADVISORY Behavioral Health Is Essential To Health • Prevention Works • Treatment Is Effective • People Recover Gambling Problems: An Introduction for Behavioral Health Services Providers Gambling problems can co-occur with other behavioral condition. Furthermore, a variety of other problems health conditions, such as substance use disorders can be related to gambling, including victimization (SUDs). Behavioral health treatment providers need to and criminalization; social problems; and health be aware that some of their clients may have gambling issues, including higher risk for contracting sexually problems in addition to the problems for which they transmitted diseases and HIV/AIDS.7 are seeking treatment. This Advisory provides a brief Gambling problems are associated with poor health,8 introduction to pathological gambling, gambling several medical disorders, and increased medical disorder, and problem gambling. The Resources section utilization—perhaps adding to the country’s healthcare lists sources for additional information. costs.9 People with pathological gambling tend to have Gambling is defined as risking something of value, lower self-appraisal of physical and mental health usually money, on the outcome of an event decided at functioning than those who gamble little or not at least partially by chance.1 Lottery tickets, bingo games, all; people with gambling problems are significantly blackjack at a casino, the Friday night poker game, the more likely than low-risk individuals to rate their office sports pool, gambling Web sites, horse and dog health as poor. People with gambling problems are racing, animal fights, and slot machines—there are also more likely to have received expensive medical now more opportunities to gamble than ever before. -

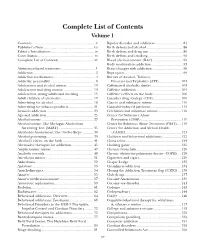

Complete List of Contents Volume 1 Contents

Complete List of Contents Volume 1 Contents .....................................................................v Bipolar disorder and addiction .............................. 84 Publisher’s Note .......................................................vii Birth defects and alcohol ....................................... 86 Editor’s Introduction ............................................... ix Birth defects and drug use ..................................... 89 Contributors ............................................................. xi Birth defects and smoking ...................................... 90 Complete List of Contents ......................................xv Blood alcohol content (BAC) ................................ 92 Body modification addiction .................................. 93 Abstinence-based treatment ..................................... 1 Brain changes with addiction ................................. 96 Addiction ................................................................... 2 Bupropion ............................................................... 99 Addiction medications .............................................. 4 Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Addictive personality ................................................ 8 Firearms and Explosives (ATF) ....................... 101 Adolescents and alcohol misuse............................. 10 Caffeinated alcoholic drinks ................................ 103 Adolescents and drug misuse ................................. 13 Caffeine addiction ............................................... -

12-STEP PROGRAMS Disclosure

American Osteopathic Academy of Addiction Medicine Essentials of Addiction Medicine 12-STEP PROGRAMS Disclosure ◼The narrator has No Disclosures Alcoholics Anonymous “The Preamble” • Alcoholics Anonymous is a fellowship of men and women who share their experience, strength and hope with each other that they may solve their common problem and help others to recover from alcoholism. Alcoholics Anonymous (cont’d) • The only requirement for membership is a desire to stop drinking. There are no dues or fees for A.A. membership; we are self-supporting through our own contributions. A.A. is not allied with any sect, denomination, politics, organization or institution; does not wish to engage in any controversy, neither endorses nor opposes any causes. Our primary purpose is to stay sober and help other alcoholics to achieve sobriety. “Alcoholics Anonymous has been called the most significant phenomenon in the history of ideas in the 20th Century” Quote from Lasker Award Citation to AA, 1951. Why the 12-Step Programs? • They really work! • The spiritual approach of AA and NA has helped millions of people who want to stop drinking and using drugs. • Most effective way of staying sober. • Essential source for clinicians. • Know how to refer and support. • 12-Steps adapted to deal with over 200 human problem behaviors. The Great Challenge for Addiction Treatment • To integrate: 12-Step Spirituality, Addiction Psychiatry, Neurobiology, And 21st Century Psychopharmacology. TWO MODELS Model One ABSTINENCE, SPIRITUALITY, ACCOUNTABILITY, SERVICE; HIGHER POWER AS A SPIRITUAL CONCEPT, FAITH AND BIG BOOK AUTHORITY, SPONSORSHIP, GROUP CONSCIENCE., 12-STEP RECOVERY AS A WAY OF LIFE. Model Two DUAL DIAGNOSIS, PERSONAL IDENTITY AS PSYCHIATRIC PATIENT, MEDICAL AUTHORITY, PRESCRIPTION AUTHORITY, SCIENCE AND PSYCHOTHERAPY, PSYCHOPHARMACOLOGY, PSYCHIATRY (AND PSYCHIATRISTS) AS HIGHER POWER. -

Support Groups in the Cincinnati Area

Support Groups in the Cincinnati Area Abuse/Domestic Violence Support Groups Transform Adult Program- updated March 2021 YWCA of Greater Cincinnati Batterers' Intervention & Prevention Program is designed for men who have histories of causing harm by abusing their intimate partners. This program is primarily educational and informational. Participants may be court ordered to attend, referred by other agencies or self-referred. Participants will have the opportunity to identify thinking and behavior patterns, learn and practice new ways of pro-social thinking and non-abusive behaviors, as well as transform their family live and strengthen relationships. 898 Walnut Street Cincinnati, OH 45202 Morning & Evening options $20.00 enrollment fee, $20.00 per session Contact office coordinator for information and referral form: 513-241-7090 www.ywcacincinnati.org Domestic Violence Support Group- updated March 21 Women Helping Women A Domestic Violence Support Group Multiple groups offered These support groups are conducted to help survivors cope with confusion, anger, and fear often experienced after episodes of sexual assault and domestic violence. Groups enable survivors to share their experiences, feelings, and provide them support to overcome their fears and feelings of isolation. Locations: 215 E 9th St, Cincinnati, OH 45202 6 S 2nd St #828, Hamilton, OH 45011 Call for dates, times and more information: 513-381-5610 www.womenhelpingwomen.org Women's Group- updated March 2021 IKRON This counseling group addresses women’s issues as they relate to a variety of skills and emotional issues such as parenting, relationships, stress management, self-esteem, confidence, career, etc. All women seeking support are welcome. Need to register and complete application. -

Power Point Presentation

9/14/2010 History & Issues In Co-Occurring Disorder Module 1 4 An oversimplified picture of the behavioral healthcare service systems in the US Mental Health Services Substance Abuse Services / Leadership-psychiatrists / Leadership-A mixture of / Staffing-psychologists, social recovering people, business workers, nurses, MFTs people, professionals / Role of medications- / Staffing-paraprofessionals, Substantial with increasing role of / Impact of behavioral professionals therapies research- / Role of medications and Substantial behavior therapies-Informal / Knowledge of substance use / Knowledge of psychiatric disorders and their treatment disorders-informal Minimal / Role of self-help-Substantial / Education on SA minimal / Role of self-help-Minimal 5 Current Trends 2010 /Mental Health /Addiction Utilizing medications to /Utilizing Peer and control symptoms Self Help Groups understanding of meds significant /Education formalized 6 2 9/14/2010 Why are substance use disorders treated in separate systems from other psychiatric disorders? How has the split occurred between substance use disorders and other psychiatric disorders? / Before 1970 in the US, research and treatment for alcoholism and drug abuse were administered out of the National Institute of Mental Health. / A number of factors prompted the separation of alcoholism/drug abuse into their own specialty areas, distinct and separate from general psychiatry. 7 Why are substance use disorders treated in separate systems from other psychiatric disorders? /A pervasive perception existed among the public and policymakers that the professional fields of psychiatry and medicine were extraordinarily unsuccessful in providing treatment to addicts and alcoholics; and, that there was a tendency within psychiatry (and psychology) to avoid alcoholics and addicts as inherently untreatable individuals, incapable of insight. -

2012 WSC Report

2012 Annual Debtors Anonymous World Service Conference Seattle, WA 26th Annual Report August 15-19, 2012 2012 Convocation Minutes, General Service Board Reports, Committee Reports, and Caucus Reports Campus of Seattle Pacific University Seattle, Washington USA August 15 – 19, 2012 Anonymity This report is provided to the delegates who attended the 2012 World Service Conference, and contains complete contact information for all participants. The information in this report should be kept confidential to protect anonymity. WSC Report Availability A version of this report without full names and contact information will be made available to the Fellowship and other interested parties on the Debtors Anonymous Website at www.debtorsanonymous.org. Accuracy Every effort has been made to publish an accurate and error-free version of the Conference proceedings. Please notify the General Service Office of any errors before the 2013 Conference. © 2012 Debtors Anonymous General Service Board, Inc. P.O. Box 920888, Needham, MA 02492 Email: [email protected] 1 2012 Annual Debtors Anonymous World Service Conference Seattle, WA 26th Annual Report August 15-19, 2012 Table of Contents Table of Contents .......................................................................................................................................... 2 SECTION 1: CHRONOLOGICAL SUMMARY OF 2012 WSC MOTIONS ............................................................ 4 SECTION 2: ALPHABETICAL SUMMARY OF 2012 WSC MOTIONS ...............................................................