RESEARCH ARTICLE Ovarian Developmental Variation in the Primitively Eusocial Wasp Ropalidia Marginata Suggests a Gateway to Work

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Evolution of Cooperative Breeding in the African Cichlid Fish, Neolamprologus Pulcher

Biol. Rev. (2011), 86, pp. 511–530. 511 doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2010.00158.x The evolution of cooperative breeding in the African cichlid fish, Neolamprologus pulcher Marian Wong∗ and Sigal Balshine Department of Psychology, Neuroscience & Behaviour, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, L8S 4L8, Canada (Received 14 December 2009; revised 5 August 2010; accepted 16 August 2010) ABSTRACT The conundrum of why subordinate individuals assist dominants at the expense of their own direct reproduction has received much theoretical and empirical attention over the last 50 years. During this time, birds and mammals have taken centre stage as model vertebrate systems for exploring why helpers help. However, fish have great potential for enhancing our understanding of the generality and adaptiveness of helping behaviour because of the ease with which they can be experimentally manipulated under controlled laboratory and field conditions. In particular, the freshwater African cichlid, Neolamprologus pulcher, has emerged as a promising model species for investigating the evolution of cooperative breeding, with 64 papers published on this species over the past 27 years. Here we clarify current knowledge pertaining to the costs and benefits of helping in N. pulcher by critically assessing the existing empirical evidence. We then provide a comprehensive examination of the evidence pertaining to four key hypotheses for why helpers might help: (1) kin selection; (2) pay-to-stay; (3) signals of prestige; and (4) group augmentation. For each hypothesis, we outline the underlying theory, address the appropriateness of N. pulcher as a model species and describe the key predictions and associated empirical tests. For N. -

Leary, C.J. 2014. Close-Range Vocal Signals Elicit a Stress Response in Male Green Treefrogs

Animal Behaviour 96 (2014) 39e48 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Animal Behaviour journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/anbehav Close-range vocal signals elicit a stress response in male green treefrogs: resolution of an androgen-based conflict * Christopher J. Leary Department of Biology, The University of Mississippi, Oxford, MS, U.S.A. article info Male courtship signals often stimulate the production of sex steroids in both female and male receivers. fi Article history: Such effects bene t signallers by increasing receptivity in females, but impose costs on signallers by Received 11 March 2014 promoting sexual behaviour and aggression in male competitors. To resolve this androgen-based conflict, Initial acceptance 24 April 2014 males should use strategies that suppress sex steroid production in rival males. In green treefrogs, Hyla Final acceptance 7 July 2014 cinerea, chorus sounds (i.e. advertisement calls from aggregates of males) are known to stimulate Published online 17 August 2014 androgen production in receiver males. Here, I examined whether males of this species counter these MS. number: A14-00205R effects by eliciting an endocrine stress response in male conspecifics during close-range vocal in- teractions. I show that corticosterone (CORT) levels were higher in males that lost vocal contests in Keywords: natural choruses compared to contest winners and nonaggressive males. Testosterone levels were also acoustic signal lower in contest losers compared to nonaggressive males, but not contest winners; dihydrotesterone challenge hypothesis levels did not differ among the three groups. Aggressive and advertisement calls were then broadcast to courtship signal glucocorticoid males in an experiment that simulated close-range vocal communication. -

Behaviour of the Indian Social Wasp Ropalidia Cyathiformis on a Nest of Separate Combs(Hymenoptera:Vespidae)

J. Zool.,Lond. (1982)198,27-37 Behaviour of the Indian social wasp Ropalidia cyathiformis on a nest of separate combs(Hymenoptera:Vespidae) RAGHAVENDRAGADAGKARANDN.V.JOSHI Centrefor Theoretical.Studies,Indian Institute ofScience, Bangalore 560012, India (Accepted28 January 1982) (With 5 figuresin the text) Observations were made on a nest of Ropa/idia cyathiformis consisting of three combs. The number of eggs, larvae, pupae and adults were monitored at about 3-day intervals for a 2-month period. The behaviour of the adults was observed with special reference to the pro- portion of time spent on each of the three combs, the proportion of time spent away from the.nest site and the frequencies of dominance interactions and egglaying. The adults moved freely between the three combs suggesting that all of them and all the three combs belonged to one nest. However, most of the adults preferred combs 2 and 3 over comb I. Of the 10 animals chosen for a detailed analysis of behaviour, seven spent varying periods of time away from the nest site and often brought back food or building material. Five of the 10 animals laid at least one egg each but two adults monopolized most of the egg-laying. The animals showed a variety of dominance interactions on the basis of which they have been arranged in a dominance hierarchy. The dominant individuals laid most of the eggsand spent little or no time foraging, while the subordinate individuals spent more time foraging and laid few eggs or none. It is argued that R. cyathiformis is different from R. -

Biodiversity of Wasps Species Collected from District Karak, KP

Journal of Entomology and Zoology Studies 2018; 6(2): 21-23 E-ISSN: 2320-7078 P-ISSN: 2349-6800 Biodiversity of wasps species collected from JEZS 2018; 6(2): 21-23 © 2018 JEZS district Karak, KP, Pakistan Received: 09-01-2018 Accepted: 10-02-2018 Muhammad Arsalan, Arshad Abbas, Shafi Ullah Gul, Hameed Ur Rehman, Muhammad Arsalan Department of Zoology, GPGC, Sahibzada Muhammad Jawad, Wahid Shah and Arshad Mehmood Kohat, Pakistan Abstract Arshad Abbas Wasps are present throughout the world, mostly in tropical regions. The present research work is Department of Zoology, GPGC, Kohat, Pakistan conducted in various region of district Karak including Mithakhel, Esakchuntra, Palosa, Sabirabbadto find out wasp fauna. The fauna of wasp were observed during summer season, mostly from April- Shafi Ullah Gul September 2017. During the research survey 24 species of wasps were collected from open fields, Department of Zoology, GPGC, gardens and houses and are preserved in 70% ethanol, which belongs from 1 order Hymenoptera, 3 Kohat, Pakistan families Vespidae, Pompilidae, Ichneumonidae and 11 genera Polistes, Vespa, Dolichovespula, Vespula, Ropalidia, Cryptocheilus, Hemipepsis, Priocnemis, Anoplius, Arochnospila, Megarhyssa. Family Hameed Ur Rehman Pompilidae was the most abundant family having 12 species, family Vespidae has 11 species, while Department of Chemistry, Kohat family Ichneumonidae have 1 species. The present research survey suggests that District Karak has a University of Science and diverse wasp fauna. Similar research study is recommended on large scale to find out the remaining wasp Technology, KUST, Kohat, species in District Karak and its surrounded areas. Pakistan Keywords: wasp, fauna, family, region, district, Karak Sahibzada Muhammad Jawad Department of Zoology, Islamia College University Peshawar, Introduction KP, Pakistan In the present research study, fauna of wasp are observed in different areas of Karak to find out the pre-existing species of wasp. -

Concepts Derived from the Challenge Hypothesis T ⁎ John C

Hormones and Behavior 115 (2019) 104550 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Hormones and Behavior journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/yhbeh Review article Concepts derived from the Challenge Hypothesis T ⁎ John C. Wingfielda, , Wolfgang Goymannb, Cecilia Jalabertc,d, Kiran K. Somac,d,e a Department of Neurobiology, Physiology and Behavior, University of California, One Shields Avenue, Davis, CA 95616, USA b Department of Behavioral Neurobiology, Max Planck Institute for Ornithology, Seewiesen, Germany c Department of Zoology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada d Djavad Mofawaghian Centre for Brain Health, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada e Department of Psychology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: The Challenge Hypothesis was developed to explain why and how regulatory mechanisms underlying patterns of State levels testosterone secretion vary so much across species and populations as well as among and within individuals. The Neurosteroids hypothesis has been tested many times over the past 30 years in all vertebrate groups as well as some in- Songbird vertebrates. Some experimental tests supported the hypothesis but many did not. However, the emerging con- Aggression cepts and methods extend and widen the Challenge Hypothesis to potentially all endocrine systems, and not only Testosterone control of secretion, but also transport mechanisms and how target cells are able to adjust their responsiveness to Mass spectrometry Androgens circulating levels of hormones independently of other tissues. The latter concept may be particularly important in explaining how tissues respond differently to the same hormone concentration. Responsiveness of the hy- pothalamo-pituitary-gonad (HPG) axis to environmental and social cues regulating reproductive functions may all be driven by gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) or gonadotropin-inhibiting hormone (GnIH), but the question remains as to how different contexts and social interactions result in stimulation of GnRH or GnIH release. -

UC Santa Barbara Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title How Collective Personality, Behavioral Plasticity, Information, and Fear Shape Collective Hunting in a Spider Society Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4pm302q6 Author Wright, Colin Morgan Publication Date 2018 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara How Collective Personality, Behavioral Plasticity, Information, and Fear Shape Collective Hunting in a Spider Society A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Ecology, Evolution and Marine Biology by Colin M. Wright Committee in charge: Professor Jonathan Pruitt, Chair Professor Erika Eliason Professor Thomas Turner June 2018 The dissertation of Colin M. Wright is approved. ____________________________________________ Erika Eliason ____________________________________________ Thomas Turner ____________________________________________ Jonathan Pruitt, Committee Chair April 2018 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my Ph.D. advisor, Dr. Jonathan Pruitt, for supporting me and my research over the last 5 years. I could not imagine having a better, or more entertaining, mentor. I am very thankful to have had his unwavering support through academic as well as personal challenges. I am also extremely thankful for all the members of the Pruitt Lab (Nick Keiser, James Lichtenstein, and Andreas Modlmeier), as well as my cohorts at both the University of Pittsburgh and UCSB that have been my closest friends during graduate school. I appreciate Dr. Walter Carson at the University of Pittsburgh for being an unofficial second mentor to me during my time there. Most importantly, I would like to thank my family, Rill (mother), Tom (father), and Will (brother) Wright. -

Terrestrial Arthropod Surveys on Pagan Island, Northern Marianas

Terrestrial Arthropod Surveys on Pagan Island, Northern Marianas Neal L. Evenhuis, Lucius G. Eldredge, Keith T. Arakaki, Darcy Oishi, Janis N. Garcia & William P. Haines Pacific Biological Survey, Bishop Museum, Honolulu, Hawaii 96817 Final Report November 2010 Prepared for: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Pacific Islands Fish & Wildlife Office Honolulu, Hawaii Evenhuis et al. — Pagan Island Arthropod Survey 2 BISHOP MUSEUM The State Museum of Natural and Cultural History 1525 Bernice Street Honolulu, Hawai’i 96817–2704, USA Copyright© 2010 Bishop Museum All Rights Reserved Printed in the United States of America Contribution No. 2010-015 to the Pacific Biological Survey Evenhuis et al. — Pagan Island Arthropod Survey 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ......................................................................................................... 5 Background ..................................................................................................................... 7 General History .............................................................................................................. 10 Previous Expeditions to Pagan Surveying Terrestrial Arthropods ................................ 12 Current Survey and List of Collecting Sites .................................................................. 18 Sampling Methods ......................................................................................................... 25 Survey Results .............................................................................................................. -

Taxonomy of the Ropalidia Flavopicta-Complex (Hymenoptera: Vespidae: Polistinae)

Taxonomy of the Ropalidia flavopicta-complex (Hymenoptera: Vespidae: Polistinae) J. Kojima Kojima, J. Taxonomy of the Ropalidia flavopicta-complex (Hymenoptera: Vespidae: Polistinae). Zool. Med. Leiden 70 (22), 31.xii.1996: 325-347, figs 1-106.— ISSN 0024-0672. J. Kojima, Natural History Laboratory, Faculty of Science, Ibaraki University, Mito 310 Japan (until December 1996: Nationaal Natuurhistorisch Museum, Postbus 9517, 2300 RA Leiden, The Nether• lands). Key words: Hymenoptera; Vespidae; Polistinae; Ropalidia flavopicta; Southeast Asia. The taxonomy of the "species" treated as subspecies of Ropalidia flavopicta (= R. flavopicta-complex) by van der Vecht (1962) were reexamined. Four forms in the complex other than the species in the Philip• pine Islands are concluded to be valid species: R. flavopicta (Smith), R. javanica van der Vecht, R. ochra- cea van der Vecht, and R. ornaticeps (Cameron). The two subspecies of the Philippine species, R. flavo- brunnea van der Vecht, namely lapiniga Kojima and iracunda Kojima, are sunk into the nominate spe• cies. A new species is described based on a female listed under "R. flavopicta flavobrunnea " by van der Vecht (1962). Introduction Van der Vecht (1941, 1962) reviewed the Oriental species of Ropalidia Guerin- Meneville, 1831 and recognized nine species in the subgenus "Icarielia Dalla Torre, 1904" (van der Vecht, 1962: 41-42). The subgenus, according to him, is defined by the lack of a raised carina on the mesepisternum (= epicnemial carina) morphologically and by enveloped nests behaviourally. The species recognized in "Icarielia" by van der Vecht are: R. aristocratica (de Saussure, 1853), R. decorata (Smith, 1858), R. flavopic• ta (Smith, 1857), R. -

Americant MUSEUM Novrtates PUBLISHED by the AMERICAN MUSEUM of NATURAL HISTORY CENTRAL PARK WEST at 79TH STREET, NEW YORK, N.Y

AMERICANt MUSEUM Novrtates PUBLISHED BY THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY CENTRAL PARK WEST AT 79TH STREET, NEW YORK, N.Y. 10024 Number 3199, 96 pp. May 16, 1997 Catalog of Species in the Polistine Tribe Ropalidiini (Hymenoptera: Vespidae) JUN-ICHI KOJIMA4A AND JAMES M. CARPENTER2 ABSTRACT A comprehensive catalog of species in the pol- don, are designated. Lectotypes of three species istine tribe Ropalidiini, which comprises four gen- described by Smith in the Hope Entomological era endemic to the Old World (Ropalidia, Para- Collections, Oxford, and of one species described polybia, Polybioides, and Belonogaster), is pre- by Cheesman in the Natural History Museum, sented. A total of 225 species and subspecies are London, are designated. Nomenclatural changes treated as valid in Ropalidia, nine in Parapolybia, include transfer of Odynerus jaculator Smith, six (and one variety) in Polybioides, and 85 in 1871, to Ropalidia, NEW COMBINATION; and Belonogaster. Lectotypes of 14 species described synonymy of Icaria sericea Cameron, 1911, with by Cameron in the Zoologisch Museum, Amster- Ropalidia wollastoni (Meade-Waldo, 1912), NEW dam, and in the Natural History Museum, Lon- SYNONYMY. INTRODUCTION The subfamily Polistinae of the wasp fam- the largest polistine genus, whose distribu- ily Vespidae, consisting of more than 800 tion is confined to the New World; Ropali- species in 27 genera (Carpenter, 1996; see diini includes the four genera endemic to the also Carpenter et al., 1996), can be divided Old World including Oceania (namely, Be- into four monophyletic tribes (Carpenter, lonogaster, Parapolybia, Polybioides, and 1993). The tribe Polistini comprises the large Ropalidia); and Epiponini includes the re- cosmopolitan genus Polistes; the tribe Mis- maining 21 New World, swarm-founding chocyttarini consists only of Mischocyttarus, genera. -

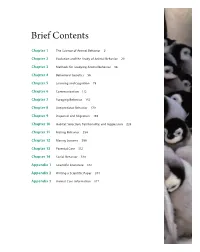

Brief Contents

B r i e f C o n t e n t s Chapter 1 The Science of Animal Behavior 2 Chapter 2 Evolution and the Study of Animal Behavior 20 Chapter 3 Methods for Studying Animal Behavior 38 Chapter 4 Behavioral Genetics 56 Chapter 5 Learning and Cognition 78 Chapter 6 Communication 112 Chapter 7 Foraging Behavior 142 Chapter 8 Antipredator Behavior 170 Chapter 9 Dispersal and Migration 196 Chapter 10 Habitat Selection, Territoriality, and Aggression 226 Chapter 11 Mating Behavior 254 Chapter 12 Mating Systems 286 Chapter 13 Parental Care 312 Chapter 14 Social Behavior 338 A p p e n d i x 1 Scientific Literature 372 Appendix 2 Writing a Scientific Paper 374 Appendix 3 Animal Care Information 377 C o n t e n t s P r e f a c e x x i i i Chapter 1 The Science of Animal Behavior 2 1.1 Animals and their behavior are an integral part of human society 4 Recognizing and defi ning behavior 5 Measuring behavior: elephant ethograms 5 1.2 Th e scientifi c method is a formalized way of knowing about the natural world 6 Th e importance of hypotheses 7 Th e scientifi c method 7 Correlation and causality 10 Hypotheses and theories 11 Social sciences and the natural sciences 11 1.3 Animal behavior scientists test hypotheses to answer research questions about behavior 12 Hypothesis testing in wolf spiders 12 Negative results and directional hypotheses 13 Generating hypoth eses 14 Hypotheses from mathematical models 14 1.4 Anthropomorphic explanations of behavior assign human emotions to animals and can be diffi cult to test 15 1.5 Scientifi c knowledge is generated and -

Comparative Morphology of the Stinger in Social Wasps (Hymenoptera: Vespidae)

insects Article Comparative Morphology of the Stinger in Social Wasps (Hymenoptera: Vespidae) Mario Bissessarsingh 1,2 and Christopher K. Starr 1,* 1 Department of Life Sciences, University of the West Indies, St Augustine, Trinidad and Tobago; [email protected] 2 San Fernando East Secondary School, Pleasantville, Trinidad and Tobago * Correspondence: [email protected] Simple Summary: Both solitary and social wasps have a fully functional venom apparatus and can deliver painful stings, which they do in self-defense. However, solitary wasps sting in subduing prey, while social wasps do so in defense of the colony. The structure of the stinger is remarkably uniform across the large family that comprises both solitary and social species. The most notable source of variation is in the number and strength of barbs at the tips of the slender sting lancets that penetrate the wound in stinging. These are more numerous and robust in New World social species with very large colonies, so that in stinging human skin they often cannot be withdrawn, leading to sting autotomy, which is fatal to the wasp. This phenomenon is well-known from honey bees. Abstract: The physical features of the stinger are compared in 51 species of vespid wasps: 4 eumenines and zethines, 2 stenogastrines, 16 independent-founding polistines, 13 swarm-founding New World polistines, and 16 vespines. The overall structure of the stinger is remarkably uniform within the family. Although the wasps show a broad range in body size and social habits, the central part of Citation: Bissessarsingh, M.; Starr, the venom-delivery apparatus—the sting shaft—varies only to a modest extent in length relative to C.K. -

A Checklist of Ropalidiini Wasps (Hymenoptera: Vespidae; Polistinae) in Indochina

Arch. Biol. Sci., Belgrade, 66 (3), 1061-1074, 2014 DOI:10.2298/ABS1403061P A CHECKLIST OF ROPALIDIINI WASPS (HYMENOPTERA: VESPIDAE; POLISTINAE) IN INDOCHINA PHONG HUY PHAM Department of Experimental Entomology, Institute of Ecology and Biological Resources, 18 Hoang Quoc Viet, Cau Giay, Hanoi, Vietnam Abstract – As a basis for intensive study of the taxonomy and biogeography of Ropalidiini wasps in Indochina (Hy- menoptera: Vespidae: Polistinae), a checklist of Ropalidiini wasps (Hymenoptera: Vespidae) is presented. A total of 57 Ropalidiini species and subspecies belonging to three genera from Indochina are listed, together with information of the type material deposited in the Natural History Collection, Ibaraki University, Japan (IUNH) and the Institute of Ecology and Biological Resources (IEBR). References of their distribution in Indochina are also provided. Key words: Bio-indicators; Himalaya; pollinators; Ropalidia; Vietnam; Vespid wasps. INTRODUCTION because they are at the top-position in a food web of terrestrial arthropods (or even animals) as well as The hymenopteran family Vespidae, with more than visiting various flowers for nectar as their own en- 5 000 species worldwide, is divided into six sub- ergy source, they are pollinators of many plants (Ko- families. They are Euparagiinae, Masarinae, Eumeni- jima, 1993; Carpenter and Wenzel, 1999; Khuat et nae, Stenogastrinae, Polistinae and Vespinae with 10 al., 2004). These considerations suggest that vespid species in one genus, 344 species in 14 genera, 3 579 wasps play important roles in an ecosystem, and can species in 210 genera, 58 species in 7 genera, 958 spe- be good bioindicators for environmental conditions cies in 26 genera and 69 species in 4 genera, respec- and/or habitat perturbation (Itô, 1984; Carpenter, tively (Pickett and Capenter, 2010).