The Judgments and Legacy of Nuremberg

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Defending the Emergence of the Superior Orders Defense in the Contemporary Context

Goettingen Journal of International Law 2 (2010) 3, 871-892 Defending the Emergence of the Superior Orders Defense in the Contemporary Context Jessica Liang Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................ 872 A. Introduction .......................................................................................... 872 B. Superior Orders and the Soldier‘s Dilemma ........................................ 872 C. A Brief History of the Superior Orders Defense under International Law ............................................................................................. 874 D. Alternative Degrees of Attributing Criminal Responsibility: Finding the Right Solution to the Soldier‘s Dilemma ..................................... 878 I. Absolute Defense ................................................................................. 878 II. Absolute Liability................................................................................. 880 III.Conditional Liability ............................................................................ 881 1. Manifest Illegality ..................................................................... 881 2. A Reasonableness Standard ...................................................... 885 E. Frontiers of the Defense: Obedience to Civilian Orders? .................... 889 I. Operation under the Rome Statute ....................................................... 889 II. How far should the Defense of Superior Orders -

From the Nuremberg Trials to the Memorial Nuremberg Trials

Presse- und Öffentlichkeitsarbeit Memorium Nürnberger Prozesse Hirschelgasse 9-11 90403 Nürnberg Telefon: 0911 / 2 31-66 89 Telefon: 0911 / 2 31-54 20 Telefax: 0911 / 2 31-1 42 10 E-Mail: [email protected] www.museen.nuernberg.de – Press Release From the Nuremberg Trials to the Memorial Nuremberg Trials Nuremberg’s name is linked with the NSDAP Party Rallies held here between 1933 and 1938 and – Presseinformation with the „Racial Laws“ adopted in 1935. It is also linked with the trials where leading representatives of the Nazi regime had to answer for their crimes in an international court of justice. Between 20 November, 1945, and 1 October, 1946, the International Military Tribunal’s trial of the main war criminals (IMT) was held in Court Room 600 at the Nuremberg Palace of Justice. Between 1946 and 1949, twelve follow-up trials were also held here. Those tried included high- ranking representatives of the military, administration, medical profession, legal system, industry Press Release and politics. History Two years after Germany had unleashed World War II on 1 September, 1939, leading politicians and military staff of the anti-Hitler coalition started to consider bringing to account those Germans responsible for war crimes which had come to light at that point. The Moscow Declaration of 1943 and the Conference of Yalta of February 1945 confirmed this attitude. Nevertheless, the ideas – Presseinformation concerning the type of proceeding to use in the trial were extremely divergent. After difficult negotiations, on 8 August, 1945, the four Allied powers (USA, Britain, France and the Soviet Union) concluded the London Agreement, on a "Charter for The International Military Tribunal", providing for indictment for the following crimes in a trial based on the rule of law: 1. -

Hans Kammler, Hitler's Last Hope, in American Hands

WORKING PAPER 91 Hans Kammler, Hitler’s Last Hope, in American Hands By Frank Döbert and Rainer Karlsch, August 2019 THE COLD WAR INTERNATIONAL HISTORY PROJECT WORKING PAPER SERIES Christian F. Ostermann and Charles Kraus, Series Editors This paper is one of a series of Working Papers published by the Cold War International History Project of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, D.C. Established in 1991 by a grant from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Cold War International History Project (CWIHP) disseminates new information and perspectives on the history of the Cold War as it emerges from previously inaccessible sources from all sides of the post-World War II superpower rivalry. Among the activities undertaken by the Project to promote this aim are the Wilson Center's Digital Archive; a periodic Bulletin and other publications to disseminate new findings, views, and activities pertaining to Cold War history; a fellowship program for historians to conduct archival research and study Cold War history in the United States; and international scholarly meetings, conferences, and seminars. The CWIHP Working Paper series provides a speedy publication outlet for researchers who have gained access to newly-available archives and sources related to Cold War history and would like to share their results and analysis with a broad audience of academics, journalists, policymakers, and students. CWIHP especially welcomes submissions which use archival sources from outside of the United States; offer novel interpretations of well-known episodes in Cold War history; explore understudied events, issues, and personalities important to the Cold War; or improve understanding of the Cold War’s legacies and political relevance in the present day. -

Nuremberg and Beyond: Jacob Robinson, International Lawyer

Loyola of Los Angeles International and Comparative Law Review Volume 39 Number 1 Special Edition: The Nuremberg Laws Article 12 and the Nuremberg Trials Winter 2017 Nuremberg and Beyond: Jacob Robinson, International Lawyer Jonathan Bush Columbia University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/ilr Recommended Citation Jonathan Bush, Nuremberg and Beyond: Jacob Robinson, International Lawyer, 39 Loy. L.A. Int'l & Comp. L. Rev. 259 (2017). Available at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/ilr/vol39/iss1/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola of Los Angeles International and Comparative Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BUSH MACRO FINAL*.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 1/24/17 7:22 PM Nuremberg and Beyond: Jacob Robinson, International Lawyer JONATHAN A. BUSH* Jacob Robinson (1889–1977) was one of the half dozen leading le- gal intellectuals associated with the Nuremberg trials. He was also argu- ably the only scholar-activist who was involved in almost every interna- tional criminal law and human rights battle in the two decades before and after 1945. So there is good reason for a Nuremberg symposium to include a look at his remarkable career in international law and human rights. This essay will attempt to offer that, after a prefatory word about the recent and curious turn in Nuremberg scholarship to biography, in- cluding of Robinson. -

German History Reflected

The Detlev Rohwedder Building German history reflected GFE = 1/2 Formathöhe The Detlev Rohwedder Building German history reflected Contents 3 Introduction 44 Reunification and Change 46 The euphoria of unity 4 The Reich Aviation Ministry 48 A tainted place 50 The Treuhandanstalt 6 Inception 53 The architecture of reunification 10 The nerve centre of power 56 In conversation with 14 Courage to resist: the Rote Kapelle Hans-Michael Meyer-Sebastian 18 Architecture under the Nazis 58 The Federal Ministry of Finance 22 The House of Ministries 60 A living place today 24 The changing face of a colossus 64 Experiencing and creating history 28 The government clashes with the people 66 How do you feel about working in this building? 32 Socialist aspirations meet social reality 69 A stroll along Wilhelmstrasse 34 Isolation and separation 36 Escape from the state 38 New paths and a dead-end 72 Chronicle of the Detlev Rohwedder Building 40 Architecture after the war – 77 Further reading a building is transformed 79 Imprint 42 In conversation with Jürgen Dröse 2 Contents Introduction The Detlev Rohwedder Building, home to Germany’s the House of Ministries, foreshadowing the country- Federal Ministry of Finance since 1999, bears wide uprising on 17 June. Eight years later, the Berlin witness to the upheavals of recent German history Wall began to cast its shadow just a few steps away. like almost no other structure. After reunification, the Treuhandanstalt, the body Constructed as the Reich Aviation Ministry, the charged with the GDR’s financial liquidation, moved vast site was the nerve centre of power under into the building. -

Nuremberg Academy Annual Report 2018

Annual Report International Nuremberg Principles Academy 1 Imprint The Annual Report 2018 has been Executive Board: published by the International Klaus Rackwitz (Director), Nuremberg Principles Academy. Dr. Viviane Dittrich (Deputy Director) It is available in English, German Edited by: and French and can be ordered Evelyn Müller at [email protected] Layout: or be downloaded on the website Martin Küchle Kommunikationsdesign www.nurembergacademy.org. Photos: Egidienplatz 23 International Nuremberg Principles Academy 90403 Nuremberg, Germany p. 9 Strathmore University, p. 20 Wayamo T + 49 (0) 911.231.10379 Foundation F + 49 (0) 911.231.14020 Printed by: [email protected] Druckwerk oHG Table of Contents 2 Foreword 5 The International Nuremberg Principles Academy 7 A Forum for Dialogue 8 • Events 14 • Network and Cooperation 19 Capacity Building 25 Research 29 Publications and Resources 32 Communications 34 Organization 37 Partners and Sponsors We proudly present the second edition of the Annual Report of the International Nuremberg Principles Academy. It reflects the activities and the achieve ments of the Nuremberg Academy throughout the year of 2018. It was another year of growth for the Nu Foreword remberg Academy with an increased num ber of events and activities at a peak level. Important anniversaries such as the 70th anniversary of the judgment of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East in Tokyo and the 20th anniversary of the adoption of the Rome Statute have been reflected in the Academy’s work and activities. Major international conferences – as far as we can see the largest of their kind, dedicated to these important dates worldwide – were held in Nuremberg in May and in October. -

Nuremberg Icj Timeline 1474-1868

NUREMBERG ICJ TIMELINE 1474-1868 1474 Trial of Peter von Hagenbach In connection with offenses committed while governing ter- ritory in the Upper Alsace region on behalf of the Duke of 1625 Hugo Grotius Publishes On the Law of Burgundy, Peter von Hagenbach is tried and sentenced to death War and Peace by an ad hoc tribunal of twenty-eight judges representing differ- ent local polities. The crimes charged, including murder, mass Dutch jurist and philosopher Hugo Grotius, one of the principal rape and the planned extermination of the citizens of Breisach, founders of international law with such works as Mare Liberum are characterized by the prosecution as “trampling under foot (On the Freedom of the Seas), publishes De Jure Belli ac Pacis the laws of God and man.” Considered history’s first interna- (On the Law of War and Peace). Considered his masterpiece, tional war crimes trial, it is noted for rejecting the defense of the book elucidates and secularizes the topic of just war, includ- superior orders and introducing an embryonic version of crimes ing analysis of belligerent status, adequate grounds for initiating against humanity. war and procedures to be followed in the inception, conduct, and conclusion of war. 1758 Emerich de Vattel Lays Foundation for Formulating Crime of Aggression In his seminal treatise The Law of Nations, Swiss jurist Emerich de Vattel alludes to the great guilt of a sovereign who under- 1815 Declaration Relative to the Universal takes an “unjust war” because he is “chargeable with all the Abolition of the Slave Trade evils, all the horrors of the war: all the effusion of blood, the The first international instrument to condemn slavery, the desolation of families, the rapine, the acts of violence, the rav- Declaration Relative to the Universal Abolition of the Slave ages, the conflagrations, are his works and his crimes . -

BOOK REVIEW: Telford Taylor: Courts of Terror Paul Sherman

Brooklyn Journal of International Law Volume 3 | Issue 1 Article 6 1976 BOOK REVIEW: Telford Taylor: Courts of Terror Paul Sherman Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/bjil Recommended Citation Paul Sherman, BOOK REVIEW: Telford Taylor: Courts of Terror, 3 Brook. J. Int'l L. (1976). Available at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/bjil/vol3/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brooklyn Journal of International Law by an authorized editor of BrooklynWorks. BOOK REVIEW Courts of Terror. TELFORD TAYLOR. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1976. Pp. xi, 184. $6.95. New York: Vintage Books (Random House), 1976. Pp. xi, 184. $1.65 (pap.). Reviewed by Paul Sherman* In Courts of Terror, Professor Telford Taylor has produced a work of advocacy with a two-fold purpose: to create "an account of the prostitution of Soviet justice to serve State ends,"' and to publicize this failure of justice in order to "aid or comfort the victims of these abuses, and their friends and relatives."' He achieves the first goal, in large part, by describing his efforts and those of a number of attorneys and law professors to secure the release of twenty-three prisoners in the Soviet Union. In so doing, he describes the unusual procedures and occasionally extraordi- nary application of criminal provisions under which these prison- ers were convicted. Whether publication of this work will achieve his second goal is a subjective judgment, but as he notes in Chap- ter 10, disclosure may serve to "systematize the spreading of in- formation about these cases" and continue whatever momentum 3 has been achieved. -

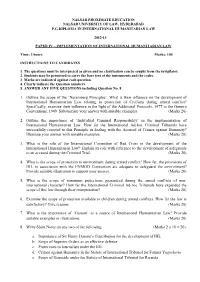

1. Outline the Scope of the 'Nuremberg Principles'. What Is

NALSAR PROXIMATE EDUCATION NALSAR UNIVERSITY OF LAW, HYDERABAD P.G.DIPLOMA IN INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW 2012-13 PAPER IV – IMPLEMENTATION OF INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW Time: 3 hours Marks: 100 INSTRUCTIONS TO CANDIDATES 1. The questions must be interpreted as given and no clarification can be sought from the invigilator. 2. Students may be permitted to carry the bare text of the instruments and the codes. 3. Marks are indicated against each question. 4. Clearly indicate the Question numbers. 5. ANSWER ANY FIVE QUESTIONS including Question No. 8 1. Outline the scope of the ‘Nuremberg Principles’. What is their influence on the development of International Humanitarian Law relating to protection of Civilians during armed conflict? Specifically, examine their influence in the light of the Additional Protocols, 1977 to the Geneva Conventions, 1949. Substantiate your answer with suitable examples. (Marks 20) 2. Outline the importance of ‘Individual Criminal Responsibility’ in the implementation of International Humanitarian Law. How far the International Ad-hoc Criminal Tribunals have successfully resorted to this Principle in dealing with the Accused of Crimes against Humanity? Illustrate your answer with suitable examples. (Marks 20) 3. What is the role of the International Committee of Red Cross in the development of the International Humanitarian Law? Explain its role with reference to the development of safeguards to an accused during the Criminal Trial. (Marks 20) 4. What is the scope of protection to environment during armed conflict? How far, the provisions of IHL in association with the ENMOD Convention are adequate to safeguard the environment? Provide suitable illustration to support your answer. -

Bibliography Primary Sources Biddle, Francis. "The

Bibliography Primary Sources Biddle, Francis. "The Nürnberg Trial." In Perspectives on the Nuremberg Trial, 200-12. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008. Francis Biddle, the primary American judge of the IMT, wrote this short piece only months after the conclusion of the trials. His purpose was largely to clarify common misconceptions about the trial - primarily their "root in victor's justice." This article helped clarify some essential points of the trial and its justification for me. Dodd, Christopher J., and Lary Bloom. Letters from Nuremberg: My Father's Narrative of a Quest for Justice. New York: Crown Pub., 2007. Print. This is a collection of letters written by Thomas Dodd to his family members back home detailing the events of the International Military Tribunal and his involvement in it. These provide a unique first-hand look at what the prosecution team was doing in Nuremberg and helped provide a better understanding of the prosecutors' strategy and mentality throughout the trial. European Advisory Council. Charter of the International Military Tribunal - Annex to the Agreement for the Prosecution and Punishment of the Major War Criminals of the uropean Axis ("London Agreement"). August 8, 1945. The Charter of the IMT, commonly known as the "London Charter," authorized the formation of the International Military Tribunal and outlined the rules and procedures it was to follow. This is one of the central documents of the trial, and its contents were drawn upon in future trials and in the Rome Statute. It was incredibly important to this project, and it is featured in full on the website. -

JUDGEMENT at NUREMBERG 1946 Fact Sheet

JUDGEMENT AT NUREMBERG 1946 Fact Sheet On the morning of October 16, 1946, five of the Nazi war criminals who had been tried and convicted at the Nuremburg Trials were seated at the prison morning mess table. Their breakfast was interrupted by a United States Soldier who asked for their autographs. They had never seen this person before and his unfamiliar face aroused the suspicions of Herman Goering. When he inquired as to the identity of the mysterious soldier he learned that Master Sergeant John Woods was the official hangman for the prisoners and that his real purpose had not been collecting autographs but estimating bodyweight of three of the five men seated at the table. The gallows had been secretly constructed in the prison gym and the executions would begin that evening. Goering was first on the list. He had stated earlier that if he was to be executed, it should be by firing squad instead of being hung like a common criminal. Early that evening Goering asked the guard to go into the luggage room and bring him some of his personal belongings. Within an hour, he had committed suicide by biting down on a glass capsule filled with cyanide that he had secretly hidden in his belongings. Sergeant Woods, on hearing of Goering’s death, was enraged at missing the opportunity of hanging the infamous war criminal, but continued with the other hangings as scheduled. Woods was a professional who had hanged hundreds of people and these executions were no different. The routine for hanging each convicted criminal was the same. -

Nazi Medicine and the Nuremberg Trials Also by Paul Julian Weindling

Nazi Medicine and the Nuremberg Trials Also by Paul Julian Weindling HEALTH, RACE AND GERMAN POLITICS BETWEEN NATIONAL UNIFICATION AND NAZISM, 1870–1945 EPIDEMICS AND GENOCIDE IN EASTERN EUROPE, 1890–1945 Nazi Medicine and the Nuremberg Trials From Medical War Crimes to Informed Consent Paul Julian Weindling © Paul Julian Weindling 2004 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 2004 978-1-4039-3911-1 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The author has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2004 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 Companies and representatives throughout the world PALGRAVE MACMILLAN is the global academic imprint of the Palgrave Macmillan division of St. Martin’s Press, LLC and of Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. Macmillan® is a registered trademark in the United States, United Kingdom and other countries. Palgrave is a registered trademark in the European Union and other countries. ISBN 978-0-230-50700-5 ISBN 978-0-230-50605-3 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/9780230506053 This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources.