DOCUMENT RESUME Development Needs of Three Classroom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RHYTHM & BLUES...63 Order Terms

5 COUNTRY .......................6 BEAT, 60s/70s ..................71 AMERICANA/ROOTS/ALT. .............22 SURF .............................83 OUTLAWS/SINGER-SONGWRITER .......23 REVIVAL/NEO ROCKABILLY ............85 WESTERN..........................27 PSYCHOBILLY ......................89 WESTERN SWING....................30 BRITISH R&R ........................90 TRUCKS & TRAINS ...................30 SKIFFLE ...........................94 C&W SOUNDTRACKS.................31 AUSTRALIAN R&R ....................95 C&W SPECIAL COLLECTIONS...........31 INSTRUMENTAL R&R/BEAT .............96 COUNTRY AUSTRALIA/NEW ZEALAND....31 COUNTRY DEUTSCHLAND/EUROPE......32 POP.............................103 COUNTRY CHRISTMAS................33 POP INSTRUMENTAL .................136 BLUEGRASS ........................33 LATIN ............................148 NEWGRASS ........................35 JAZZ .............................150 INSTRUMENTAL .....................36 SOUNDTRACKS .....................157 OLDTIME ..........................37 EISENBAHNROMANTIK ...............161 HAWAII ...........................38 CAJUN/ZYDECO ....................39 DEUTSCHE OLDIES ..............162 TEX-MEX ..........................39 KLEINKUNST / KABARETT ..............167 FOLK .............................39 Deutschland - Special Interest ..........167 WORLD ...........................41 BOOKS .........................168 ROCK & ROLL ...................43 BOOKS ...........................168 REGIONAL R&R .....................56 DISCOGRAPHIES ....................174 LABEL R&R -

Soundtrack and Garnering Accolades for Their Debut Album “Remind Me in Three Days.” Check out Our Exclusive Interview on Page 7

Ver su s Entertainment & Culture at Vanderbilt DECEMBER 3—DECEMBER 9, 2008 VOL. 46, NO. 26 “Abstract Progressive” rapping duo The Knux are giving Vincent Chase his soundtrack and garnering accolades for their debut album “Remind Me in Three Days.” Check out our exclusive interview on page 7. We saw a lot of movies over break. We weigh in on which to see and … from which to fl ee. “808s and Heartbreaks” is really good. Hey, Kanye, hey. PLACES TO GO, PEOPLE TO SEE THURSDAY, DECEMBER 4 FRIDAY, DECEMBER 5 SATURDAY, DECEMBER 6 The Regulars Harley Allen Band — Station Inn Parachute Musical and KinderCastle with Noises Carols & Cocoa — Barnes and Noble, Cool THE RUTLEDGE The go-to joint for bluegrass in the Music City features Harley Allen, 10 — The Mercy Lounge and Cannery Ballroom Springs 410 Fourth Ave. S. 37201 Part of the Mercy Lounge’s Winter of Dreamz musical showcase, a well-known song writer who’s worked with Garth Brooks, Dierks Need to get into the Christmas spirit? The Battle Ground Academy 782-6858 Bentley and Gary Allan to name a few. Make sure to see this living Friday’s event showcases Parachute Musical and KinderCastle along Middle School Chorus will lead you in some of your favorite seasonal legend in action. ($10, 9 p.m.) with opener Noises 10. Head to the Mercy Lounge to enjoy some carols as you enjoy delicious hot chocolate. (Free, 11 a.m., 1701 MERCY LOUNGE/CANNERY live local music and $2.50 pints courtesy of Winter of Dreamz co- Mallory Lane, Brentwood) presenter Sweetwater 420. -

The Newsletter of the National Society for the Preservation of Covered Bridges, Inc

The Newsletter of the National Society for the Preservation of Covered Bridges, Inc. Winter 2020/2021 Consumed by Wildfire The former Great Northern Railway Bridge near Colfax, Washington was destroyed by a wildfire on September 7, 2020. See the feature article on page 6. In this issue Membership ...................................... 2 Bridge Rescue in Kentucky ........................ 8 President’s Message ........................ 3 Western Indiana Tour ................................ 9 NSPCB Meeting Information ............. 4 News of Members ............................... 10-11 Covered Bridge Meetings & Events .. 5 Book Review ........................................... 12 Colfax Bridge Destroyed ................... 6 Help Save Our Bridges ............................ 13 Goodpasture Bridge Saved ............... 7 Covered Bridge News ......................... 14-27 NSPCB Newsletter Winter 2020 / 2021 The NSPCB Newsletter is Welcome New Members published quarterly to keep the membership informed of current David Bell, Tacoma, Washington bridge news and upcoming events. Spencer Bennett & Linda McGuire, Henniker, New Hampshire Terry Bodine, Covington, Indiana NSPCB Contacts Pat and Angie Boggs, Flatwoods, Kentucky President Christopher Garlick, Lake Mary, Florida Bill Caswell Richard Kennett, Pinckney, Michigan 535 2nd NH Tpke Michael Kent, Newburyport, Massachusetts Hillsboro, NH 03244-4601 Joseph Merkel, East Brunswick, New Jersey [email protected] William Miller, Pickerington, Ohio Corresponding Secretary Gary Riemenschneider, Columbus, Ohio Robert Watts Debbie Roark, Columbus, Ohio 126 Merrimac St. Unit 21 Karen Stokes, Spring, Texas Newburyport, MA 01950 508-878-7854 [email protected] Welcome New LIFE Member #200 Vigo County Parks and Recreation Department, Membership Dues and Address Terre Haute, Indiana Changes Jennifer Caswell Meet a Member – John Smolen Membership Chair 535 2nd NH Tpke [Editor’s note: A dinner scheduled in John’s honor in November Hillsboro, NH 03244-4601 was cancelled due to COVID concerns. -

Case Index FLPINELLASPROD

Case Index FLPINELLASPROD Version: Public Filed Date: 10/01/2019 to 09/28/2020 Sorted By: Case Number Probate/Mental Health Section 003 Section 004 Section 003 Case Number Style Case Type File Date Case Status Date Case Subtype Active Case Status 19-009152-ES IN RE: THE ESTATE OF PATRICIA ANN KING FORMAL ADMINISTRATION 10/01/2019 10/01/2019 OPEN 19-009166-ES IN RE: THE ESTATE OF KEVIN PATRICK KEARNS SUMMARY ADMINISTRATION 10/01/2019 10/01/2019 OVER $1000 OPEN 19-009168-ES IN RE: THE ESTATE OF MICHAEL BAYBAK FORMAL ADMINISTRATION 10/01/2019 10/01/2019 OPEN 19-009169-ES IN RE: THE ESTATE OF JOHN A XANDER FORMAL ADMINISTRATION 10/01/2019 10/01/2019 OPEN 19-009188-ES IN RE: THE ESTATE OF MAY LOIS GILYARD FORMAL ADMINISTRATION 10/02/2019 10/02/2019 OPEN 19-009193-ES IN RE: THE ESTATE OF MARILYN CATHERINE SKIFF FORMAL ADMINISTRATION 10/02/2019 10/02/2019 OPEN 19-009195-ES IN RE: THE ESTATE OF LYDIA A RIOLO FORMAL ADMINISTRATION 10/02/2019 10/02/2019 OPEN 19-009197-ES IN RE: THE ESTATE OF LILA A. SAMUELS SUMMARY ADMINISTRATION 10/02/2019 10/02/2019 UNDER $1000 OPEN 19-009209-ES IN RE: THE ESTATE OF ROBERT RICHARD PENNING SUMMARY ADMINISTRATION 10/02/2019 10/02/2019 OVER $1000 OPEN 19-009216-ES IN RE: THE ESTATE OF PATRICIA WILKINS FORMAL ADMINISTRATION 10/02/2019 10/02/2019 OPEN 19-009217-ES IN RE: THE ESTATE OF LOUISE TANNEY MEEK SUMMARY ADMINISTRATION 10/02/2019 10/02/2019 UNDER $1000 OPEN Printed on 09/29/2020 at 2:01 AM Page 1 of 271 Case Index FLPINELLASPROD Version: Public Filed Date: 10/01/2019 to 09/28/2020 Sorted By: Case Number Probate/Mental -

Ctba Newsletter 1607

Volume 38, No. 7 © Central Texas Bluegrass Association July 2016 Sunday, July 3: Band Scramble and Garage Sale at Threadgill’s s in previous years, our annual band scramble and musical garage sale will take place at A Threadgill’s North location (6416 North Lamar, Austin) from 2-6 PM on Sunday. We test the boundaries of musical chaos while you watch. Here’s the schedule: 2:00 - 4:30: Buy new/used music-related items (instruments, CDs, DVDs, strings, books, etc.). 3:00: Up to six new, on-the-spot bands are formed from bluegrass/old-time pickers with stage experi- ence who sign up ahead of time. 4:00 - 6:00 Bands perform their tunes. Last year we had a total of 51 pickers in seven dif- ferent bands and raised over $2400. The garage sale portion of the event will be where the buffet is usu- ally set up. We’ll have CDs, T-shirts, magazines, instructional materials, maybe even some instru- ments for sale, and if you want to renew your mem- bership or join the CTBA for the first time, there’ll be some board members at the tables to help you. Last year we had some late arrivals who wanted to sign up even after some of the bands had started practicing. This year, it will help if everyone who wants to scramble can sign up by 3 PM so Eddie can get the bands properly sorted out. Mikaela, Derek, and Logan Pausewang, this year’s CTBA Jim Wiederhold participates in last year’s scholarship winners, will perform a few tunes for us band scramble. -

Alan Jackson

COUNCIL FILE NO. /0~051-7 COUNCIL DISTRICT NO. 13 .,/ APPROVAL FOR ACCELERATED PROCESSING DIRECT TO CITY COUNCIL The attached Council File may be processed directly to Council pursuant to the procedure approved June 26, 1990, (CF 83-1 075-S 1) without being referred to the Public Works Committee because the action on the file checked below is deemed to be routine and/or administrative in nature: _} A. Future Street Acceptance. _} B. Quitclaim of Easement(s). _} C. Dedication of Easement(s). _} D. Release of Restriction(s). _x} E. Request for Star in Hollywood Walk of Fame. _} F. Brass Plaque(s) in San Pedro Sport Walk. _} G. Resolution to Vacate or Ordinance submitted in response to Council action. _} H. Approval of plans/specifications submitted by Los Angeles County Flood Control District. APPROVAL/DISAPPROVAL FOR ACCELERATED PROCESSING: APPROVED DISAPPROVED* 1. Council Office of the District 2. Public Works Committee Chairperson *DISAPPROVED FILES WILL BE REFERRED TO THE PUBLIC WORKS COMMITTEE. Please return to Council Index Section, Room 615 City Hall City Clerk Processing: Date notice and report copy mailed to interested parties advising of Council date for this item. Date scheduled in Council. AFTER COUNCIL ACTION: ____J Send copy of adopted report to the Real Estate Section, Development Services Division, Bureau of Engineering (Mail Stop No. 515) for further processing. ___}Other: PLEASE DO NOT DETACH THIS APPROVAL SHEET FROM THE COUNCIL FILE ACCELERATED REVIEW PROCESS- E Office ofthe City Engineer Los Angeles, California To the Honorable Council Of the City of Los Angeles > MAR 2 5 211111 Honorable Members: C. -

August Troubadour

FREE SAN DIEGO ROUBADOUR Alternative country, Americana, roots, folk, Tblues, gospel, jazz, and bluegrass music news January 2007 www.sandiegotroubadour.com Vol. 6, No. 4 what’s inside Welcome Mat ………3 Contributors Michael Cleveland Full Circle.. …………4 Apex Music Recordially, Lou Curtiss Front Porch... ………6 Kev Rones/S.D. Guitar Society Kite Flying Society Parlor Showcase …8 Emerging Young Artists Ramblin’... …………10 Bluegrass Corner Zen of Recording Hosing Down Radio Daze Highway’s Song. …12 Dixie Dregs/Steve Morse Of Note. ……………13 Grand Canyon Sundown Peggy Lebo Renata Youngblood Jennifer Jayden Dee Ray ‘Round About ....... …14 January Music Calendar The Local Seen ……15 Photo Page Phil Harmonic Sez: “To be a warrior is to learn to be genuine in every moment of your life.” — Chögyam Trungpa JANUARY 2007 SAN DIEGO TROUBADOUR welcome mat e r i u Michael Cleveland G c M SAN DIEGO m i J ROUBADOUR : o Brings Flaming Hot t Alternative country, Americana, roots, folk, o h Tblues, gospel, jazz, and bluegrass music news Bluegrass to San Diego P MISSION CONTRIBUTORS by Dwight Worden Bill Monroe, Jim and Jesse To promote, encourage, and provide an FOUNDERS alternative voice for the great local music that McReynolds, Ralph Stanley, Mac Ellen and Lyle Duplessie hat do you get when you Weisman, Doc Watson, Larry Sparks, is generally overlooked by the mass media; Liz Abbott put a blow torch to the Doyle Lawson, Dale Ann Bradley, namely the genres of alternative country, Kent Johnson W Michael Cleveland Americana, roots, folk, blues, gospel, jazz, and bow of a fiddle? Red hot Rhonda Vincent, and JD Crowe among bluegrass. -

Ballots Must Be Returned Before Voting Closes at 5 P.M. on Friday, May 24

MusicRow Awards Final Nominations by Sarah Skates usicRow is celebrating the 25th anniversary of its annual awards show, and kicking off the voting period with today’s announcement of nominees. The MusicRow Awards, Nashville’s longest running music industry trade publication honors, will be hosted by ASCAP at the performing rights organization’s offices on Tuesday, June 25 at 5:30 p.m. The MusicRow Awards started in 1989 with a salute to the Top 10 Album All-Star Musicians, a category that Mcontinues today. The inaugural winners included Eddie Bayers for Drums, John Jarvis on Keyboards and Mark O’Conner for Miscellaneous Instruments. The magazine cover featured artists J.C. Crowley, Clint Black, Foster & Lloyd and Lorrie Morgan. Inside the issue was an interview with Joe Casey from CBS, and Bill Mayne and Bob Saporiti from Warner Bros. about methods of securing radio airplay. Robert K. Oermann’s famous Disc-Claimer column included reviews of Johnny Cash’s “Ballad of a Teenage Queen,” Lynn Anderson’s “How Many Hearts” Ballots must be returned before voting closes at 5 p.m. on Friday, May 24. Page 2 Page 4 Page 3 and Jack Hutchinson’s “Don’t Close the Door on Me,” and Toby Keith. where the tough-as-nails critic opined, “Rush him to the The debut album from Mercury Nashville artist Kacey Emergency Room, quick: I think he has the stomach Musgraves entered the country chart at No. 1. Same cramps.” Trailer Different Park is being hailed by critics and fans. In 2013, the nominations continue to reflect the Musgraves is on the road with Kenny Chesney’s No significant amount of quality music being created in Shoes Nation stadium tour. -

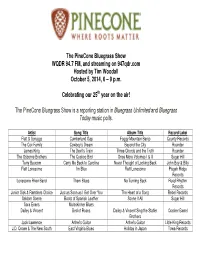

The Pinecone Bluegrass Show WQDR 94.7 FM, and Streaming on 947Qdr.Com Hosted by Tim Woodall October 5, 2014, 6 – 9 P.M

The PineCone Bluegrass Show WQDR 94.7 FM, and streaming on 947qdr.com Hosted by Tim Woodall October 5, 2014, 6 – 9 p.m. Celebrating our 25 th year on the air! The PineCone Bluegrass Show is a reporting station in Bluegrass Unlimited and Bluegrass Today music polls. Artist Song Title Album Title Record Label Flatt & Scruggs Cumberland Gap Foggy Mountain Banjo County Records The Cox Family Cowboy’s Dream Beyond the City Rounder James King The Devil’s Train Three Chords and the Truth Rounder The Osborne Brothers The Cuckoo Bird Once More Volumes I & II Sugar Hill Terry Baucom Carry Me Back to Carolina Never Thought of Looking Back John Boy & Billy Flatt Lonesome I’m Blue Flatt Lonesome Pisgah Ridge Records Lonesome River Band Them Blues No Turning Back Rural Rhythm Records Junior Sisk & Ramblers Choice Just as Soon as I Get Over You The Heart of a Song Rebel Records Seldom Scene Boots of Spanish Leather Scene it All Sugar Hill Sara Evans Muleskinner Blues Dailey & Vincent Bed of Roses Dailey & Vincent Sing the Statler Cracker Barrel Brothers Jack Lawrence Arthel’s Guitar Arthel’s Guitar Little King Records J.D. Crowe & The New South East Virginia Blues Holiday in Japan Towa Records Russell Moore & IIIrd Tyme Out Pretty Little Girl from Galax Prime Tyme Rural Rhythm Records Ricky Skaggs You Can’t Hurt Ham Music to My Ears Skaggs Family Records Balsam Range Trains I Missed Trains I Missed Mountain Home Alison Krauss & Union Station I’ll Remember You, Love, in My So Long So Wrong Rounder Prayers Alan Mullen Big Sandy Heartwood Sessions jam -

Antimusic.Com: Pearl Jam Under Review DVD Review

4/1/2011 antiMusic.com: Pearl Jam Under Revie… Jealous Haters Since 1998! Home | News | Reviews | Day In Rock | Photos | RockNewsWire | Singled Out | Tour Dates/Tix | Feeds Pearl Jam Under Review DVD by Kevin Wierzbicki . This film is not authorized by Pearl Jam or their record label, but really all that means is that certain material could not be used in its making. That didn't keep the filmmakers from putting together a pretty good piece that traces the band's origins through a nexus to Seattle bands Green River, Mother Love Bone and Shadow with commentary from insiders like journalist Greg Prato, former Rolling Stone editor Joe Levy and Kurt Cobain biographer Charles Cross. Intelligent analysis, performance and interview snippets and lots of Pearl Jam factoids are . News Reports woven into this well-edited and quick-moving documentary that covers the band's career through 2008. Pearl Jam - Under • Day in Rock: Review Velvet Revolver Confirm Pearl Jam, Chrome ... Recording With Corey Best Price $13.06 Taylor- AC/DC Drug or Buy New $17.99 Conviction Overturned- Police Recommend Privacy Information Charges Against Vince Neil- Big Audio Dynamite- Info and Links • Yesterday's Report: Pearl Jam Under Review DVD AC/DC, Ozzy, Dio, Whitesnake Rockers Preview and Purchase This CD Online For Japan Benefit To Be Webcast- Paramore Recording New Album- Visit the official homepage New Staind Album Coming- DevilDriver Name Replacement- More articles for this artist more . Subscribe To Day in tell a friend about this article Rock . • Digest: Steven Adler Idol?- Death at ex- Grateful Dead Show- Guitarist Rushed To ...end The Hospital- Guns N' Roses Surgery- Billy Joel Won't Tell All- Arcade Fire- Kid Rock Tour- more • Day in Pop 5 Browns Dad Convicted- Early Kanye Leaks- Mad Men Deal Struck- Katy Perry E.T. -

Lee Perry Lost Treasures of the Ark Vol

$5.95 (U.S.), $6.95 (CAN.), £4.95 (U.K.), Y2,500 (JAPAN) iW en w 1 z IITITTILTTLTLILTTITEEITTILTITJII I IItTTII 908 #BXNCCVR 3-DIGIT #90807GEE374EM002# BLBD 715 A06 MONTY GREENLY 3740 ELM AVE # A LONG BEACH CA 90807 -3402 THE INTERNATIONAL NEWSWEEKLY OF MUSIC, VIDEO, AND HOME ENTERTAINMENT JANUARY 8, 2000 GOOD WORKS IN MUSIC NEWS The Retailers Make Merry 1- Jailers, Mass Merchants, Others See Gains Latin Jazz BY DON JEFFREY ed mall chains Musicland Stores and and ED CHRISTMAN Trans World Entertainment would NEW YORK -E- commerce, the not disclose sales figures for the hol- recording mass merchants, and free -standing iday period, reports from other music stores were whistling a happy sources indicate that these retailers' tune after Christmas, while the mall same -store sales (from units open at that's chains had less to least a year) were be cheerful about. flat for the period, winning Exhibit Examines It was a mixed which began 3rd Single Shows holiday season for NATIONAL RECORD MART 111111ER Thanksgiving U.S. music retail- AECOAUS- VIIIEUCMS week. Guthrie legacy ers, according to I According to Lopez Has legs everyone's reports from SoundScan, album BY CHRIS MORRIS chains, independents, and label sales for the five -week period that BY LARRY FLICK LOS ANGELES -Woody sources. By all reports, E- merchants ended Dec. 26 totaled 140 million NEW YORK -In the six heart! Guthrie will come home to New enjoyed another season of astounding units, up 3.1% from the 135.8 million months since issuing her York on Feb. -

Warrant Status Report 07-23-2019 08:35 Am

BURNETT COUNTY-7 Warrant Status Report 07-23-2019 08:35 am Date Date Date Case Stay Stay Status Type Issued Disposed Name of Birth Number Date Time Amount Issued Commitment 03-18-2015 A Alshushan, Abdulrahman Sultan 07-01-1984 2014TR001679 200.50 Issued Warrant - failure to appear 06-02-2017 Abbott, Alan Craig 09-19-1964 2017CM000076 0.00 Issued Warrant - failure to appear 06-02-2017 Abbott, Alan Craig 09-19-1964 2017CM000060 0.00 Issued Commitment 02-10-2008 Aguilera, Eduardo Ortiz 10-13-1960 2007TR002104 194.00 Issued Commitment 04-28-2010 Aherns, Christine E. 03-15-1991 2008FO000376 184.00 Issued Arrest warrant - complaint 08-26-2004 Ahmed, Abdirahman Mohamud 12-26-1963 2004CM000540 0.00 Issued Arrest warrant - complaint 01-19-2016 Ahmed-Campbell, Jasmeen 09-07-1977 2016CM000011 0.00 Issued Commitment 01-09-2019 Akana, Edwin Kw 08-30-1983 2009CM000197 2380.00 Issued Commitment 02-11-2008 Albrecht, Gary R., Jr. 12-14-1958 2003CM000050 324.00 Issued Arrest warrant - complaint 10-24-2007 Albrecht, Gary Raymond, Jr. 12-14-1958 2007CM000446 0.00 Issued Commitment 06-07-2018 Alyea, Justin David 11-16-1988 2013CF000172 371.00 Issued Warrant - failure to appear 09-08-2010 Amey, Thomas Klaus 03-03-1977 2010CM000241 0.00 Issued Warrant - failure to appear 06-11-2004 Anders, Leann Parker 05-20-1976 2004CM000331 0.00 Issued Commitment 03-14-2019 Anderson, Benjamin Gerald 07-08-1986 2016CM000218 500.00 Issued Commitment 06-23-2015 Anderson, Eric A. 11-15-1984 2007TR000175 186.00 Issued Arrest warrant - complaint 11-27-2000 Anderson, Keith B.