(Iirc) on the August 23, 2010 Rizal Park Hostage-Taking Incident Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

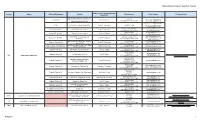

FOI Manuals/Receiving Officers Database

National Government Agencies (NGAs) Name of FOI Receiving Officer and Acronym Agency Office/Unit/Department Address Telephone nos. Email Address FOI Manuals Link Designation G/F DA Bldg. Agriculture and Fisheries 9204080 [email protected] Central Office Information Division (AFID), Elliptical Cheryl C. Suarez (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 2158 [email protected] Road, Diliman, Quezon City [email protected] CAR BPI Complex, Guisad, Baguio City Robert L. Domoguen (074) 422-5795 [email protected] [email protected] (072) 242-1045 888-0341 [email protected] Regional Field Unit I San Fernando City, La Union Gloria C. Parong (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4111 [email protected] (078) 304-0562 [email protected] Regional Field Unit II Tuguegarao City, Cagayan Hector U. Tabbun (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4209 [email protected] [email protected] Berzon Bldg., San Fernando City, (045) 961-1209 961-3472 Regional Field Unit III Felicito B. Espiritu Jr. [email protected] Pampanga (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4309 [email protected] BPI Compound, Visayas Ave., Diliman, (632) 928-6485 [email protected] Regional Field Unit IVA Patria T. Bulanhagui Quezon City (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4429 [email protected] Agricultural Training Institute (ATI) Bldg., (632) 920-2044 Regional Field Unit MIMAROPA Clariza M. San Felipe [email protected] Diliman, Quezon City (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4408 (054) 475-5113 [email protected] Regional Field Unit V San Agustin, Pili, Camarines Sur Emily B. Bordado (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4505 [email protected] (033) 337-9092 [email protected] Regional Field Unit VI Port San Pedro, Iloilo City Juvy S. -

![THE HUMBLE BEGINNINGS of the INQUIRER LIFESTYLE SERIES: FITNESS FASHION with SAMSUNG July 9, 2014 FASHION SHOW]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7828/the-humble-beginnings-of-the-inquirer-lifestyle-series-fitness-fashion-with-samsung-july-9-2014-fashion-show-667828.webp)

THE HUMBLE BEGINNINGS of the INQUIRER LIFESTYLE SERIES: FITNESS FASHION with SAMSUNG July 9, 2014 FASHION SHOW]

1 The Humble Beginnings of “Inquirer Lifestyle Series: Fitness and Fashion with Samsung Show” Contents Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines ................................................................ 8 Vice-Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines ....................................................... 9 Popes .................................................................................................................................. 9 Board Members .............................................................................................................. 15 Inquirer Fitness and Fashion Board ........................................................................... 15 July 1, 2013 - present ............................................................................................... 15 Philippine Daily Inquirer Executives .......................................................................... 16 Fitness.Fashion Show Project Directors ..................................................................... 16 Metro Manila Council................................................................................................. 16 June 30, 2010 to June 30, 2016 .............................................................................. 16 June 30, 2013 to present ........................................................................................ 17 Days to Remember (January 1, AD 1 to June 30, 2013) ........................................... 17 The Philippines under Spain ...................................................................................... -

Political Activism of Philippine Labor Migrants in Hong Kong

Diffusion in transnational political spaces: political activism of Philippine labor migrants in Hong Kong Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät der Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg i. Br vorgelegt von Stefan Rother aus Ravensburg SS 2012 Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Jürgen Rüland Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Heribert Weiland Drittgutachter: Prof. Dr. Gregor Dobler Vorsitzender des Promotionsausschusses der Gemeinsamen Kommission der Philologischen, Philosophischen und Wirtschafts- und Verhaltenswissenschaftlichen Fakultät: Prof. Dr. Hans-Helmuth Gander Datum der Fachprüfung im Promotionsfach: 26. August 2012 Table of contents List of Acronyms .................................................................................................................................................... v 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 1 Part I: Theoretical background and approach .................................................................................................... 7 2. Labour migration, transnationalism and International Relations Theory ............................................... 8 3. Transnationalism in migration studies .................................................................................................. 21 3.1. Transnational social fields ................................................................................................................ -

Philippine Political Economy 1998-2018: a Critical Analysis

American Journal of Research www.journalofresearch.us ¹ 11-12, November-December 2018 [email protected] SOCIAL SCIENCE AND HUMANITIES Manuscript info: Received November 4, 2018., Accepted November 12, 2018., Published November 30, 2018. PHILIPPINE POLITICAL ECONOMY 1998-2018: A CRITICAL ANALYSIS Ruben O Balotol Jr, [email protected] Visayas State University-Baybay http://dx.doi.org/10.26739/2573-5616-2018-12-2 Abstract: In every decision than an individual deliberates always entails economic underpinnings and collective political decisions to consider that affects the kind of decision an individual shape. For example governments play a major role in establishing tax rates, social, economic and environmental goals. The impact of economic and politics are not only limited from one's government, different perspectives and region of the globe are now closely linked imposing ideology and happily toppling down cultural threat to their interests. According to Žižek (2008) violence is not solely something that enforces harm or to an individual or community by a clear subject that is responsible for the violence. Violence comes also in what he considered as objective violence, without a clear agent responsible for the violence. Objective violence is caused by the smooth functioning of our economic and political systems. It is invisible and inherent to what is considered as normal state of things. Objective violence is considered as the background for the explosion of the subjective violence. It fore into the scene of perceptibility as a result of multifaceted struggle. It is evident that economic growth was as much a consequence of political organization as of conditions in the economy. -

Taking the Hong Kong Tour Bus Hostage Tragedy in Manila to the ICJ? Developing a Framework for Choosing International Dispute Settlement Mechanisms

Taking the Hong Kong Tour Bus Hostage Tragedy in Manila to the ICJ? Developing a Framework for Choosing International Dispute Settlement Mechanisms AMY LA* Table of Contents PROLOGUE ................................................... 674 I. THE MANILA HOSTAGE TRAGEDY: UNANSWERED QUESTIONS AND UNSERVED JUSTICE ..................... 675 A. The Calm Before the Storm ............................... 676 B. "Storming" the Bus ..................................... 677 C. Nine Lives, One Incomplete Report, and Three Forums .......... 678 D. The ICJ as the Fourth Forum? ............................. 680 H. ADJUDICATING THE HOSTAGE TRAGEDY BY THE ICJ? THE (IN)APPLICABILITY OF LEGAL STANDARDS ................. 681 A. Third-Party Dispute Settlements v. Negotiation ................. 682 B. Formal Adjudication by the ICJ v. Other Third-Party Settlements . 683 C. Re-examining the Hostage Tragedy Impasse: Why Not the ICJ? ... 684 1. Preference for Less Public Methods? The Necessity for "Airing Dirty Laundry" ..................................... 685 2. Retrospective or "Win-Lose" Situation? The Necessity for Breaking a Chain of Abuses ............................ 685 3. Unclear Laws: The Lack of Detailed, Robust Standards for Adjudication . ....................................... 687 a. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights: Or Was It Ordinary Negligence? .............................. 687 b. International Convention Against the Taking of Hostages: A Far Less Direct Method ............................ 689 III. THE ICJ OR OTHER SETTLEMENT MECHANISMS? -

A Case Study of Hong Kong SAR and Its Implications to Chinese Foreign Policy

Paradiplomacy and its Constraints in a Quasi-Federal System – A Case Study of Hong Kong SAR and its Implications to Chinese Foreign Policy Wai-shun Wilson CHAN ([email protected]) Introduction Thank for the Umbrella Movement in 2014, Hong Kong has once again become the focal point of international media. Apart from focusing the tensions built among the government, the pro-Beijing camp and the protestors on the pathway and the pace for local democratization, some media reports have linked the movement with the Tiananmen Incident, and serves as a testing case whether “One Country, Two Systems” could be uphold under the new Xin Jinping leadership.1 While academics and commentators in Hong Kong and overseas tend to evaluate the proposition from increasing presence of Beijing in domestic politics and the decline of freedoms and rights enjoyed by civil society,2 little evaluation is conducted from the perspective of the external autonomy enjoyed by Hong Kong under “One Country, Two Systems”. In fact, the Sino-British Joint Declaration and the subsequent Basic Law have defined and elaborated the scope of Hong Kong’s autonomy in conducting external relations ‘with states, regions and relevant international organizations.’ 3 It is therefore tempted to suggest that the external autonomy enjoyed by Hong Kong SAR Government serves as the other pillar of “One Country, Two Systems”, giving an unique identity of Hong Kong in global politics which may be different from that possessed by mainland China. Though officially “One Country, Two Systems” practiced in Hong Kong (and Macao) is not recognized by Beijing as a federal arrangement between the Central People’s Government and Hong Kong SAR Government, the internal and external autonomy stipulated in the Basic Law gives Hong Kong similar, to some extent even more, power as a typical federated unit. -

Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 2014

This event is dedicated to the Filipino People on the occasion of the five- day pastoral and state visit of Pope Francis here in the Philippines on October 23 to 27, 2014 part of 22- day Asian and Oceanian tour from October 22 to November 13, 2014. Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 ―Mercy and Compassion‖ a Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 2014 Contents About the project ............................................................................................... 2 About the Theme of the Apostolic Visit: ‗Mercy and Compassion‘.................................. 4 History of Jesus is Lord Church Worldwide.............................................................................. 6 Executive Branch of the Philippines ....................................................................... 15 Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines ....................................................................... 15 Vice Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines .............................................................. 16 Speaker of the House of Representatives of the Philippines ............................................ 16 Presidents of the Senate of the Philippines .......................................................................... 17 Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the Philippines ...................................................... 17 Leaders of the Roman Catholic Church ................................................................ 18 Pope (Roman Catholic Bishop of Rome and Worldwide Leader of Roman -

Basic Law and Hong Kong's Bilateral Relations

External Relations of Hong Kong: The Most Neglected Subject in International Relations? Colonial Law: Promulgated by the UK Basic Law: As Authorized by the NPC of PRC › No Nullifying Power › Full Sovereignty from PRC The Central People's Government shall be responsible for the foreign affairs relating to the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People's Republic of China shall establish an office in Hong Kong to deal with foreign affairs. The Central People's Government authorizes the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region to conduct relevant external affairs on its own in accordance with this Law. Representatives of the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region may, as members of delegations of the Government of the People's Republic of China, participate in negotiations at the diplomatic level directly affecting the Region conducted by the Central People's Government. The Hong Kong Special Administrative Region may on its own, using the name ""Hong Kong, China "", maintain and develop relations and conclude and implement agreements with foreign states and regions and relevant international organizations in the appropriate fields, including the economic, trade, financial and monetary, shipping, communications, tourism, cultural and sports fields. WTO: “Tariff” APEC: “Economy” FIFA: “Domestic League” The application to the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of international agreements to which the People's Republic of China is or becomes a party shall be decided by the Central People's Government, in accordance with the circumstances and needs of the Region, and after seeking the views of the government of the Region. -

Duterte's Killer Cops

2018 SOPA AWARDS NOMINATION BISHOPDUTERTE’Sfor INVESTIGATIVE KILLER REPORTING COPS Part 1 BLOOD ON THE STREET: The aftermath of what police said was a shoot-out with three drug suspects beneath MacArthur Bridge in central Manila in June. The three men were pronounced dead on arrival at hospital. REUTERS/Dondi Tawatao Duterte’s killer cops BY CLARE BALDWIN AND ANDREW R.C. MARSHALL JUNE 29 – DECEMBER 19 MANILA/ QUEZON CITY 2018 SOPA AWARDS INVESTIGATIVE REPORTING 1 DUTERTE’S KILLER COPS Part 1 It was at least an hour, according to resi- dents, before the victims were thrown into a truck and taken to hospital in what a police report said was a bid to save their lives. Old Balara’s chief, the elected head of the district, told Reuters he was perplexed. They were already dead, Allan Franza said, so why take them to hospital? An analysis of crime data from two of Metro Manila’s five police districts and interviews with doctors, law enforcement officials and victims’ families point to one answer: Police Philippine were sending corpses to hospitals to destroy evidence at crime scenes and hide the fact that they were executing drug suspects. police use Thousands of people have been killed since President Rodrigo Duterte took office on June 30 last year and declared war on what he called “the drug menace.” Among them were hospitals to the seven victims from Old Balara who were declared dead on arrival at hospital. A Reuters analysis of police reports covering hide drug the first eight months of the drug war reveals hundreds of cases like those in Old Balara. -

IFSSO) November 18-20, 2011

20th General Conference of the International Federation of Social Science Organizations (IFSSO) November 18-20, 2011. Lyceum of the Philippines University, Batangas City, Philippines CONFERENCE PROGRAM 18 November 2011 (Friday) REGISTRATION 7:00-8:30 a.m. Venue: Freedom Hall OPENING PROGRAM Opening Remarks – Prof. Teruyuki Komatsu (IFSSO President) 8:30-9:30 a.m. Welcome Address – Mr. Peter P. Laurel (President, Lyceum of the Philippines University) Overview of Conference Program – Dr. Esmenia R. Javier (Executive Vice President, Lyceum of the Philippines University) KEYNOTE ADDRESS: Beyond the Reflexive Borders of the Western World’s Social Science System 9:30-10:00 a.m. Dr. Michael Kuhn (World Social Sciences and Humanities Network, Germany) 10:00-10:30 a.m. Break PLENARY SESSION 1: Human Security: Country Perspectives Managing Social Hazards: Path to Sustainable Human Security in Africa – Samuel Marfo (University for Development Studies, Ghana) 10:30-12:00 noon Family Security Over Life Cycle from Thai Experience – Sirinapa Kunphoommarl and Somsak Srisontisuk (Khon Kaen University, Thailand) Tourism and Community Security in Bali – I Ketut Ardhana (Udayana University, Indonesia) Deconstructing Human Security in the Philippines – Chester B. Cabalza (National Defense College of the Philippines) 12:00-1:00 p.m. Lunch Break SESSION A1: Theoretical and Methodological Approaches SESSION A2: Disciplinal Perspectives Moderator: Nestor T. Castro Moderator: Leon R. Ramos Venue: Freedom Hall Venue: Multimedia Room The Concept of Human Security from a Theoretical and A Philosophical Investigation on Human Security Using the Problem Methodological Approach – Estrella D. Solidum (National Research of Evil According to St. Thomas Aquinas and Siddhartha Gautama Council of the Philippines) Buddha – Jerwin M. -

Congressional Record O H Th PLENARY PROCEEDINGS of the 17 CONGRESS, FIRST REGULAR SESSION 1 P 907 H S ILIPPINE House of Representatives

PRE RE SE F N O T A E T S I V U E S Congressional Record O H th PLENARY PROCEEDINGS OF THE 17 CONGRESS, FIRST REGULAR SESSION 1 P 907 H S ILIPPINE House of Representatives Vol. 4 Monday, May 8, 2017 No. 86 CALL TO ORDER As Your children, we never cease to be faced with social, political, economic and environmental At 4:00 p.m., Deputy Speaker Frederick “Erick” challenges. We acknowledge that these challenges make F. Abueg called the session to order. us stronger and firmer in love and faith. But we need You always to be with us in order that we will not falter, THE DEPUTY SPEAKER (Rep. Abueg). The that we will not get lost, that we will not be afraid, and session is now called to order. that we will make only decisions that will follow Your will and Your wishes. NATIONAL ANTHEM We are a people who depend on You for guidance and wisdom. We pray that You will lead us always to THE DEPUTY SPEAKER (Rep. Abueg). Everybody the way of the righteous for the well-being of all. We is requested to rise for the singing of the National ask these in the name of the Almighty God. Amen. Anthem. THE DEPUTY SPEAKER (Rep. Abueg). The Dep. Everybody rose to sing the Philippine National Majority Leader is recognized. Anthem. REP. MERCADO. Mr. Speaker, I move that we THE DEPUTY SPEAKER (Rep. Abueg). Please defer the calling of the roll. remain standing for a minute of silent prayer and meditation—I stand corrected, we will have the THE DEPUTY SPEAKER (Rep. -

“License to Kill”: Philippine Police Killings in Duterte's “War on Drugs

H U M A N R I G H T S “License to Kill” Philippine Police Killings in Duterte’s “War on Drugs” WATCH License to Kill Philippine Police Killings in Duterte’s “War on Drugs” Copyright © 2017 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-34488 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org MARCH 2017 ISBN: 978-1-6231-34488 “License to Kill” Philippine Police Killings in Duterte’s “War on Drugs” Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Key Recommendations ..................................................................................................... 24 Methodology .................................................................................................................... 25 I.