The Forest of Pendle in the Seventeenth Century, Part Two' 11

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 400Th Anniversary of the Lancashire Witch-Trials: Commemoration and Its Meaning in 2012

The 400th Anniversary of the Lancashire Witch-Trials: Commemoration and its Meaning in 2012. Todd Andrew Bridges A thesis submitted for the degree of M.A.D. History 2016. Department of History The University of Essex 27 June 2016 1 Contents Abbreviations p. 3 Acknowledgements p. 4 Introduction: p. 5 Commemorating witch-trials: Lancashire 2012 Chapter One: p. 16 The 1612 Witch trials and the Potts Pamphlet Chapter Two: p. 31 Commemoration of the Lancashire witch-trials before 2012 Chapter Three: p. 56 Planning the events of 2012: key organisations and people Chapter Four: p. 81 Analysing the events of 2012 Conclusion: p. 140 Was 2012 a success? The Lancashire Witches: p. 150 Maps: p. 153 Primary Sources: p. 155 Bibliography: p. 159 2 Abbreviations GC Green Close Studios LCC Lancashire County Council LW 400 Lancashire Witches 400 Programme LW Walk Lancashire Witches Walk to Lancaster PBC Pendle Borough Council PST Pendle Sculpture Trail RPC Roughlee Parish Council 3 Acknowledgement Dr Alison Rowlands was my supervisor while completing my Masters by Dissertation for History and I am honoured to have such a dedicated person supervising me throughout my course of study. I gratefully acknowledge Dr Rowlands for her assistance, advice, and support in all matters of research and interpretation. Dr Rowland’s enthusiasm for her subject is extremely motivating and I am thankful to have such an encouraging person for a supervisor. I should also like to thank Lisa Willis for her kind support and guidance throughout my degree, and I appreciate her providing me with the materials that were needed in order to progress with my research and for realising how important this research project was for me. -

Download Blacko and Higherford

1 Blacko and Higherford Profile Contents 1. Population.............................................................................................................................. 3 1.1. 2011 actuals.................................................................................................................... 3 1.2. Marital Status .................................................................................................................. 3 1.3. Ethnicity .......................................................................................................................... 4 1.4. Social Grade ................................................................................................................... 4 2. Labour Market ....................................................................................................................... 5 2.1. Economic Activity............................................................................................................ 5 2.2. Economic Inactivity ......................................................................................................... 5 2.3. Employment Occupations ............................................................................................... 6 2.4. Key Out-of-Work Benefits ............................................................................................... 6 3. Health .................................................................................................................................... 8 3.1. Limiting Long-Term Illness............................................................................................. -

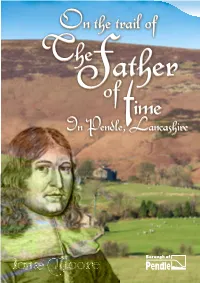

Jonas Moore Trail

1 The Pendle Witches He would walk the three miles to Burnley Grammar School down Foxendole Lane towards Jonas Moore was the son of a yeoman farmer the river Calder, passing the area called West his fascinating four and a half called John Moore, who lived at Higher White Lee Close where Chattox had lived. in Higham, close to Pendle Hill. Charged for crimes committed using mile trail goes back over 400 This was the early 17th century and John witchcraft, Chattox was hanged, alongside years of history in a little- Moore and his wife lived close to Chattox, the Alizon Device and other rival family members and known part of the Forest of Bowland, most notorious of the so called Pendle Witches. neighbours, on the hill above Lancaster, called The Moores became one of many families caught Golgotha. These were turbulent and dangerous an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. up in events which were documented in the times in Britain’s history, including huge religious It explores a hidden valley where there are world famous trial. intolerance between Protestants and Catholics. Elizabethan manor houses and evidence of According to the testimony of eighteen year Civil War the past going back to medieval times and old Alizon Device, who was the granddaughter of the alleged Pendle witch Demdike, John earlier. The trail brings to light the story of Sir Moore had quarrelled with Chattox, accusing her In 1637, at the age of 20, Jonas Moore was Jonas Moore, a remarkable mathematician of turning his ale sour. proficient in legal Latin and was appointed clerk and radical thinker that time has forgotten. -

1922 Addresses Gordon.Pdf

Addresses Biographical and Historical ALEXANDER GORDON, M.A. tc_' Sometime Lecturer in Ecclesiastical History in the University of fifanclzester VETUS PROPTER NO VUM DEPROMETIS THE LINDSEY PRESS 5 ESSEX STREET, STRAND, LONDON, W.C.2 1922 www.unitarian.org.uWdocs PREFATORY NOTE With three exceptions the following Addresses were delivered at the openings of Sessions of the Unitarian Home Missionary College, in Manchester, where the author was Principal from 1890 to 1911. The fifth Address (Salters' Hall) was delivered at the Opening Meeting of the High Pavement Historical Society, in Nottingham; the seventh (Doddridge) at Manchester College, in Oxford, in connection with the Summer Meeting of University Extension students ; The portrait prefixed is a facsimile, f~llsize, of the first issue of the original engraving by Christopher Sichem, from the eighth (Lindsey) at the Unitarian Institute, in the British Museum copy (698. a. 45(2)) of Grouwele.~,der Liverpool. vooruzaeutzster Hooft-Kettereuz, Leyden, 1607. In this volume the Addresses are arranged according to the chronology of their subjects; the actual date of delivery is added at the close of each. Except the first and the fifth, the Addresses were printed, shortly after delivery, in the Ch~istianLife newspaper ; these two (also the third) were printed separately; all have been revised, with a view as far as possible to reduce overlapping and to mitigate the use of the personal pronoun. Further, in the first Address it has been necessary to make an important correction in reference to the parentage of Servetus. Misled by the erroneous ascription to him of a letter from Louvain in 1538 signed Miguel Villaneuva (see the author's article Printed it1 Great Britain by on Servetus in the Encyclopwdia Britannica, also ELSOM& Co. -

Pilkington Bus Timetable for St Christopher's High School And

St. Christopher’s High School, Accrington School Buses • 907 • 910 ALSO AVAILABLE TO 6th FORM STUDENTS Timetable | Tickets | Tracking Tap the App New from Pilkington Bus FREE DOWNLOAD 907 Ticket Prices Cliviger Walk Mill 07:10 A Red Lees Road 07:12 A Hillcrest Ave 07:16 A Worsthorne Turning Circle 07:20 A Lindsay Park/Brownside Road 07:24 A Brunshaw Road / Bronte Avenue 07:27 A Burnley Hospital / Briercliffe Road 07:31 A Burnley Bus Station 07:35 B Tim Bobbin 07:42 B Padiham Bridge 07:48 B St Christopher's High School 08:10 St Christopher's High School 15:25 14:25 Huncoat 15:30 14:30 Hapton Inn 15:35 14:35 Padiham Bridge 15:40 14:40 Tim Bobbin 15:45 14:45 Burnley Bus Station 15:55 14:55 Burnley Hospital / Briercliffe Road 16:05 15:05 Brunshaw Road / Bronte Avenue 16:10 15:10 Lindsay Park / Brownside Road 16:14 15:14 Worsthorne Turning Circle 16:18 15:18 Hillcrest Ave 16:22 15:22 Red Lees Road 16:24 15:24 Cliviger Walk Mill 16:26 15:26 Weekly 10 Monthly Payments Annual Year Pass Up Front Zone A - over 8 miles £20.00 £76.00 £760.00 £720.00 Zone B - 3-8 miles £16.00 £60.00 £600.00 £560.00 910 Ticket Prices Foulridge Causeway 07:30 A Trawden Terminus 07:42 A Colne Skipton Rd/Gorden St 07:50 A Barrowford Road Colne (Locks) 07:55 A Barrowford Spar 08:00 A Bus Lane (nr M65) 08:02 A Nelson Bus Station (Stand 10) 08:05 A Fence Post Office 08:10 A Fence Gate 08:13 A Higham Four Alls Inn 08:17 B Padiham Slade Lane 08:20 B Padiham Bridge 08:22 B Hapton Inn 08:25 C Huncoat Station 08:30 C St Christopher's High School 08:35 St Christopher's High School -

Memories of Colne

MEMORIES OF COLNE By Mrs. Cryer, of Burnley (Formerly Miss Margaret Jane Ward, of Colne) in Collaboration with Mr. Willie Bell, of Burnley (Formerly of Colne) Reprinted from the “Colne and Nelson Times” March to August 1910 (Scanned with optical character recognition and reformatted by Craig Thornber, January 1998) -1- Introduction In 1910, Mrs. Cryer produced a series of articles for the “Colne and Nelson Times”, recalling her memories of Colne in the 1850’s. She had a remarkable memory and recounted the names and details of most of the town’s shop-keepers and their families. The book is a treasure trove for all those with family history interests in Colne in the middle of last century. To my delight, at the end of Chapter IV, I found mention of Miss Margaret Cragg, the sister of my great great grandfather. The book based on Mrs. Cryer’s articles is now very rare, so the opportunity has been taken to reproduce it. This version has been produced from a photocopy of the book by computer scanning, using an optical character recognition programme. Computer scanning is never completely accurate, particularly with punctuation marks, and when working from a document with low contrast. While the final version has been subjected to proof reading and computer based spelling checks, a few errors may remain, for which I am responsible. Many of the sentences and paragraphs are very long and the division into chapters is somewhat arbitrary, but the book has been reproduced as written. The numbering of chapter XIII has been corrected and a few changes have been made to the format for reasons of clarity. -

INSPECTION REPORT BLACKO PRIMARY SCHOOL Blacko, Nelson

INSPECTION REPORT BLACKO PRIMARY SCHOOL Blacko, Nelson, Lancashire LEA area: Lancashire Unique reference number: 119167 Headteacher: Mrs L A Harper Reporting inspector: Mr A S Kingston 21585 Dates of inspection: 7 – 8 February 2000 Inspection number: 186307 Inspection carried out under section 10 of the School Inspections Act 1996 © Crown copyright 2000 This report may be reproduced in whole or in part for non-commercial educational purposes, provided that all extracts quoted are reproduced verbatim without adaptation and on condition that the source and date thereof are stated. Further copies of this report are obtainable from the school. Under the School Inspections Act 1996, the school must provide a copy of this report and/or its summary free of charge to certain categories of people. A charge not exceeding the full cost of reproduction may be made for any other copies supplied. INFORMATION ABOUT THE SCHOOL Type of school: Primary School category: Community Age range of pupils: 4 – 11 Gender of pupils: Mixed School address: Gisburn Road Blacko Nelson Lancashire Postcode: BB9 6LS Telephone number: 01282 616669 Fax number: 01282 616669 Appropriate authority: The Governing Body Name of chair of governors: Mr A G Stephenson Date of previous inspection: 27 – 30 November 1995 Blacko Primary School - 3 INFORMATION ABOUT THE INSPECTION TEAM Team members Mr A S Kingston Registered inspector Mrs N Walker Lay inspector The inspection contractor was: Quality Education Directorate Reginald Arthur House Percy Street Rotherham S65 1ED Any concerns -

Results of Polling Station Review

Ward Name A - Barnoldswick Parliamentary Constituency Pendle Changes due to LGBCE review Coates (part) and Craven (part) Proposed Polling Polling No of Change to Polling Place District Parish (if any) County Division Polling Place District 1 electors (if any) 1 Feb 2020 March 2020 AA CQ and CR Barnoldswick (Coates Pendle Rural St Joseph’s Community Centre, Bolland 2565 No change to polling place part Ward) (Coates Ward Street, Barnoldswick BB18 5EZ for CQ, CR part moved for 2023) from Gospel Mission AB CV1 Barnoldswick (Craven Pendle Rural Independent Methodist Sunday School, 1565 No change to polling place Ward) (Barnoldswick Walmsgate, Barnoldswick, BB18 5PS North from 2023) AC CV2 None (parish meeting) Pendle Rural Independent Methodist Sunday School, 203 No change to polling place Walmsgate, Barnoldswick, BB18 5PS AD CW part Barnoldswick (Craven Pendle Rural The Rainhall Centre, Rainhall Road, 2508 No change to polling place Ward) (Barnoldswick Barnoldswick, BB18 5DR South from 2023) 6841 Ward Name B - Barrowford & Pendleside Parliamentary Constituency Pendle Changes due to LGBCE review: Merging of Wards Barrowford, Blacko & Higherford, Higham & Pendleside (part) Polling Polling No of Change to Polling Place District 1 District at 1 Parish (if any) County Division Polling Place electors (if any) March 2020 Feb 2020 BA BA Barrowford (Carr Hall Pendle Hill Victoria Park Pavilion, Carr Road, Nelson, 930 No change to polling place Ward) Lancs, BB9 7SS BB BB Barrowford (Newbridge Pendle Hill Holmefield House, Gisburn Road, 1533 No change to polling place Ward) Barrowford, BB9 8ND BC BC Barrowford (Central Pendle Hill Holmefield House, Gisburn Road, 1460 No change to polling place Ward) Barrowford, BB9 8ND BD BD Barrowford (Higherford Pendle Hill Higherford Methodist Church Hall, 890 No change to polling place Ward) Gisburn Road, Barrowford, BB9 6AW BE BE Blacko Pendle Rural Blacko County School, Beverley Road 538 No change to polling place Entrance, Blacko, BB9 6LS BF HJ Goldshaw Booth Pendle Hill St. -

EDUCATION in LANCASHIRE and CHESHIRE, 1640-1660 Read 18

EDUCATION IN LANCASHIRE AND CHESHIRE, 1640-1660 BY C. D. ROGERS, M.A., M.ED. Read 18 November 1971 HE extraordinary decades of the Civil War and Interregnum, Twhen many political, religious, and economic assumptions were questioned, have been seen until recently as probably the greatest period of educational innovation in English history. Most modern writers have accepted the traditional picture of puritan attitudes and ideas, disseminated in numerous published works, nurtured by a sympathetic government, developing into an embryonic state system of education, a picture given added colour with details of governmental and private grants to schools.1 In 1967, however, J. E. Stephens, in an article in the British Journal of Educational Studies, suggested that detailed investigations into the county of York for the period 1640 to 1660 produced a far less admirable view of the general health of educational institutions, and concluded that 'if the success of the state's policy towards education is measured in terms of extension and reform, it must be found wanting'.2 The purpose of this present paper is twofold: to examine the same source material used by Stephens, to see whether a similar picture emerges for Lancashire and Cheshire; and to consider additional evidence to modify or support his main conclusions. On one matter there is unanimity. The release of the puritan press in the 1640s made possible a flood of books and pamphlets not about education in vacuo, but about society in general, and the role of the teacher within it. The authors of the idealistic Nova Solyma and Oceana did not regard education as a separate entity, but as a fundamental part of their Utopian structures. -

51 Colne Road, Earby, BB18 6XB Offers Around £99,950

51 Colne Road, Earby, BB18 6XB Offers Around £99,950 • Garden Fronted Mid Terraced Hse • Deceptively Spacious Accomm. • Excellent Family Living Space • Convenient for Town Centre • Ent Hall and Pleasant Lounge • Generous Liv/ Din Rm with Stove • Extended Ftd Kitchen & Utility Rm • 3 Bedrooms Incl. Dormer Attic • Spacious, Fully Tiled 4 Pc Bathrm • Gas CH & PVC Double Glazing • Internal Viewing Recommended • Ideal for FTB's NO CHAIN INV. • 8 CHURCH STREET, BARNOLDSWICK, LANCASHIRE, BB18 5UT T:01282 817755 | F: 01282 817766 [email protected] | WWW.SALLYHARRISON.CO.UK Sally Harrison for themselves and for the vendor(s) or lessor(s) of this property give notice that these particulars do not constitute any part of an offer contract. Any intending purchaser must satisfy themselves by inspection or otherwise as to the condition of the premises and no warranty is given by the vendor(s), their agents, or any person in the agents employment. Comments in this description relating to the location, suitability for any purpose, aesthetic attributes and proximity to amenities is to be regarded as the agents opinion only and not a statement of fact. Room sizes quoted are approximate and given as an indication only. Offering well presented family living accommodation, this stone built, garden fronted, mid terraced house provides generously proportioned living space and would be perfect as a starter home for a first time buyer. Conveniently located only a short walk from the main shopping area and access to amenities and public transport, this substantial dwelling has the advantage of a kitchen extension and a dormer attic room and benefits from pvc double glazing and gas central heating. -

Pendle Sculpture Trail in an Atmospheric Woodland Setting

Walk distance: It is approximately 1 mile to get to the trail from Barley Car Park including one uphill stretch and one steep path. Once in Aitken Wood, which is situated on a slope, you could easily walk another mile walking around. Please wear stout footwear as there can be some muddy stretches after wet weather. Allow around 2 to 3 hours for your visit. See back cover for details on how to book a tramper vehicle for easier access to the wood for people with walking difficulties. Visit the Pendle Sculpture Trail in an atmospheric woodland setting. Art, history and nature come together against the stunning backdrop of Pendle Hill. Four artists have created a unique and intriguing range of sculptures. Their work is inspired by the history of the Pendle Witches of 1612 and the natural world in this wild and beautiful corner of Lancashire. A Witches Plaque Explore the peaceful setting of Aitken Wood to find ceramic plaques by Sarah McDade. She’s designed each one individually to symbolise the ten people from Pendle who were accused of witchcraft over 400 years ago. You’ll also find an inspiring range of sculptures, large and small, which are created from wood, steel and stone, including Philippe Handford’s amazing The Artists (as pictured here left to right) are Philippe Handford (Lead curving tree sculptures. Artist), Steve Blaylock, Martyn Bednarczuk, and Sarah McDade Philippe’s sculptures include: after dark. Reconnected 1, Reconnected had a religious vision on top There’s even a beautifully 2, The Gateway, Life Circle of nearby Pendle Hill which carved life-size figure of Philippe Handford, the lead kind of permanent trail. -

Lancashire Behaviour Support Tool

Lancashire Behaviour Support Tool Introduction Lancashire is committed to achieving excellent outcomes for its children and young people. Our aim for all our young people is for them to have the best possible start in life so that all have the opportunity to fulfill their learning potential. Schools and other settings should be safe and orderly places where all children and young people can learn and develop. The consequences of behaviour which challenges others can, if not addressed effectively, impact negatively on individual pupils and groups of pupils. The need for the Local Authority, schools and other partners to work together to address behavioural issues is essential if we are to promote high standards of achievement and attainment for all. The purpose of the Behaviour Support tool is to produce accessible, and accurate information for schools and settings in one place, on sources of training, support and advice led by Lancashire services and clear pathways in relation to meeting pupil's social, emotional and behavioural needs. Aims 1. To develop safe, calm and ordered school environments within which pupils are able to learn and develop and thrive. 2. To develop skills for emotional literacy, positive social relationships and emotional health and well-being among pupils to take into their adult lives beyond school. 3. To Improve capacity within our schools and other settings to include all our pupils including those children and young people who, at times, may present very challenging behaviour, as a result of a variety of factors originating both within the child or young person or resulting from their social environment.