Antarctica: King of Cold by Steve Whitt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amazing Antarctica – Lesson 6

Year 8 GEOGRAPHY – Ecosystems – Amazing Antarctica – Lesson 6 Title: Ecosystems – Amazing Antarctica TASK 1: write down the following WOW words. As you go through the information, write the definition for each word (you might find some of the definitions as you work through the booklet). • Precipitation = • Albedo = • Ice sheet = • Glaciers = • Food chain = TASK 2: where is Antarctica? Use the following sentence starters and complete them to explain where Antarctica is located around the world. • Antarctica is located at the _________________ pole. • Antarctica is a country/continent/city. • Nearby countries include ______________________. • The oceans that surround Antarctica are __________________________. TASK 3: watch the video and write down facts about Antarctica https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X3uT89xoKuc Antarctica TASK 4: what is the climate like in Antarctica? Read through the information below and answer the questions in red. Climate of Antarctica Antarctica can be called a desert because of its low levels of precipitation, which is mainly snow. In coastal regions, about 200 mm can fall annually. In mountainous regions and on the East Antarctica plateau, the amount is less than 50 mm annually. Evaporation is not as high as other desert regions because it is so cold, so the snow gradually builds up year after year. There are also strong winds, with recordings of up to 200 mph being made. Antarctica's seasons are opposite to the seasons that we're familiar with in the UK. Antarctic summers happen at the same time as UK winters. This is because Antarctica is in the Southern Hemisphere, which faces the Sun during our winter time. -

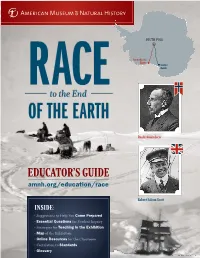

Educator's Guide

SOUTH POLE Amundsen’s Route Scott’s Route Roald Amundsen EDUCATOR’S GUIDE amnh.org/education/race Robert Falcon Scott INSIDE: • Suggestions to Help You Come Prepared • Essential Questions for Student Inquiry • Strategies for Teaching in the Exhibition • Map of the Exhibition • Online Resources for the Classroom • Correlation to Standards • Glossary ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS Who would be fi rst to set foot at the South Pole, Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen or British Naval offi cer Robert Falcon Scott? Tracing their heroic journeys, this exhibition portrays the harsh environment and scientifi c importance of the last continent to be explored. Use the Essential Questions below to connect the exhibition’s themes to your curriculum. What do explorers need to survive during What is Antarctica? Antarctica is Earth’s southernmost continent. About the size of the polar expeditions? United States and Mexico combined, it’s almost entirely covered Exploring Antarc- by a thick ice sheet that gives it the highest average elevation of tica involved great any continent. This ice sheet contains 90% of the world’s land ice, danger and un- which represents 70% of its fresh water. Antarctica is the coldest imaginable physical place on Earth, and an encircling polar ocean current keeps it hardship. Hazards that way. Winds blowing out of the continent’s core can reach included snow over 320 kilometers per hour (200 mph), making it the windiest. blindness, malnu- Since most of Antarctica receives no precipitation at all, it’s also trition, frostbite, the driest place on Earth. Its landforms include high plateaus and crevasses, and active volcanoes. -

Antarctic Primer

Antarctic Primer By Nigel Sitwell, Tom Ritchie & Gary Miller By Nigel Sitwell, Tom Ritchie & Gary Miller Designed by: Olivia Young, Aurora Expeditions October 2018 Cover image © I.Tortosa Morgan Suite 12, Level 2 35 Buckingham Street Surry Hills, Sydney NSW 2010, Australia To anyone who goes to the Antarctic, there is a tremendous appeal, an unparalleled combination of grandeur, beauty, vastness, loneliness, and malevolence —all of which sound terribly melodramatic — but which truly convey the actual feeling of Antarctica. Where else in the world are all of these descriptions really true? —Captain T.L.M. Sunter, ‘The Antarctic Century Newsletter ANTARCTIC PRIMER 2018 | 3 CONTENTS I. CONSERVING ANTARCTICA Guidance for Visitors to the Antarctic Antarctica’s Historic Heritage South Georgia Biosecurity II. THE PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT Antarctica The Southern Ocean The Continent Climate Atmospheric Phenomena The Ozone Hole Climate Change Sea Ice The Antarctic Ice Cap Icebergs A Short Glossary of Ice Terms III. THE BIOLOGICAL ENVIRONMENT Life in Antarctica Adapting to the Cold The Kingdom of Krill IV. THE WILDLIFE Antarctic Squids Antarctic Fishes Antarctic Birds Antarctic Seals Antarctic Whales 4 AURORA EXPEDITIONS | Pioneering expedition travel to the heart of nature. CONTENTS V. EXPLORERS AND SCIENTISTS The Exploration of Antarctica The Antarctic Treaty VI. PLACES YOU MAY VISIT South Shetland Islands Antarctic Peninsula Weddell Sea South Orkney Islands South Georgia The Falkland Islands South Sandwich Islands The Historic Ross Sea Sector Commonwealth Bay VII. FURTHER READING VIII. WILDLIFE CHECKLISTS ANTARCTIC PRIMER 2018 | 5 Adélie penguins in the Antarctic Peninsula I. CONSERVING ANTARCTICA Antarctica is the largest wilderness area on earth, a place that must be preserved in its present, virtually pristine state. -

Companion Q&A Fact Sheet: What Mars Reveals About Life in Our

What Mars Reveals about Life in Our Universe Companion Q&A Fact Sheet Educators from the Smithsonian’s Air and Space and Natural History Museums assembled this collection of commonly asked questions about Mars to complement the Smithsonian Science How webinar broadcast on March 3, 2021, “What Mars Reveals about Life in our Universe.” Continue to explore Mars and your own curiosities with these facts and additional resources: • NASA: Mars Overview • NASA: Mars Robotic Missions • National Air and Space Museum on the Smithsonian Learning Lab: “Wondering About Astronomy Together” Guide • National Museum of Natural History: A collection of resources for teaching about Antarctic Meteorites and Mars 1 • Smithsonian Science How: “What Mars Reveals about Life in our Universe” with experts Cari Corrigan, L. Miché Aaron, and Mariah Baker (aired March 3, 2021) Mars Overview How long is Mars’ day? Mars takes 24 hours and 38 minutes to spin around once, so its day is very similar to Earth’s. How long is Mars’ year? Mars takes 687 days, almost two Earth years, to complete one orbit around the Sun. How far is Mars from Earth? The distance between Earth and Mars changes as both planets move around the Sun in their orbits. At its closest, Mars is just 34 million miles from the Earth; that’s about one third of Earth’s distance from the Sun. On the day of this program, March 3, 2021, Mars was about 135 million miles away, or four times its closest distance. How far is Mars from the Sun? Mars orbits an average of 141 million miles from the Sun, which is about one-and-a-half times as far as the Earth is from the Sun. -

Download (Pdf, 236

Science in the Snow Appendix 1 SCAR Members Full members (31) (Associate Membership) Full Membership Argentina 3 February 1958 Australia 3 February 1958 Belgium 3 February 1958 Chile 3 February 1958 France 3 February 1958 Japan 3 February 1958 New Zealand 3 February 1958 Norway 3 February 1958 Russia (assumed representation of USSR) 3 February 1958 South Africa 3 February 1958 United Kingdom 3 February 1958 United States of America 3 February 1958 Germany (formerly DDR and BRD individually) 22 May 1978 Poland 22 May 1978 India 1 October 1984 Brazil 1 October 1984 China 23 June 1986 Sweden (24 March 1987) 12 September 1988 Italy (19 May 1987) 12 September 1988 Uruguay (29 July 1987) 12 September 1988 Spain (15 January 1987) 23 July 1990 The Netherlands (20 May 1987) 23 July 1990 Korea, Republic of (18 December 1987) 23 July 1990 Finland (1 July 1988) 23 July 1990 Ecuador (12 September 1988) 15 June 1992 Canada (5 September 1994) 27 July 1998 Peru (14 April 1987) 22 July 2002 Switzerland (16 June 1987) 4 October 2004 Bulgaria (5 March 1995) 17 July 2006 Ukraine (5 September 1994) 17 July 2006 Malaysia (4 October 2004) 14 July 2008 Associate Members (12) Pakistan 15 June 1992 Denmark 17 July 2006 Portugal 17 July 2006 Romania 14 July 2008 261 Appendices Monaco 9 August 2010 Venezuela 23 July 2012 Czech Republic 1 September 2014 Iran 1 September 2014 Austria 29 August 2016 Colombia (rejoined) 29 August 2016 Thailand 29 August 2016 Turkey 29 August 2016 Former Associate Members (2) Colombia 23 July 1990 withdrew 3 July 1995 Estonia 15 June -

ARCTIC Exploration the SEARCH for FRANKLIN

CATALOGUE THREE HUNDRED TWENTY-EIGHT ARCTIC EXPLORATION & THE SeaRCH FOR FRANKLIN WILLIAM REESE COMPANY 409 Temple Street New Haven, CT 06511 (203) 789-8081 A Note This catalogue is devoted to Arctic exploration, the search for the Northwest Passage, and the later search for Sir John Franklin. It features many volumes from a distinguished private collection recently purchased by us, and only a few of the items here have appeared in previous catalogues. Notable works are the famous Drage account of 1749, many of the works of naturalist/explorer Sir John Richardson, many of the accounts of Franklin search expeditions from the 1850s, a lovely set of Parry’s voyages, a large number of the Admiralty “Blue Books” related to the search for Franklin, and many other classic narratives. This is one of 75 copies of this catalogue specially printed in color. Available on request or via our website are our recent catalogues: 320 Manuscripts & Archives, 322 Forty Years a Bookseller, 323 For Readers of All Ages: Recent Acquisitions in Americana, 324 American Military History, 326 Travellers & the American Scene, and 327 World Travel & Voyages; Bulletins 36 American Views & Cartography, 37 Flat: Single Sig- nificant Sheets, 38 Images of the American West, and 39 Manuscripts; e-lists (only available on our website) The Annex Flat Files: An Illustrated Americana Miscellany, Here a Map, There a Map, Everywhere a Map..., and Original Works of Art, and many more topical lists. Some of our catalogues, as well as some recent topical lists, are now posted on the internet at www.reeseco.com. -

Physical Changes

How Matter Changes By Cindy Grigg Changes in matter happen around you every day. Some changes make matter look different. Other changes make one kind of matter become another kind of matter. When you scrunch a sheet of paper up into a ball, it is still paper. It only changed shape. You can cut a large, rectangular piece of paper into many small triangles. It changed shape and size, but it is still paper. These kinds of changes are called physical changes. Physical changes are changes in the way matter looks. Changes in size and shape, like the changes in the cut pieces of paper, are physical changes. Physical changes are changes in the size, shape, state, or appearance of matter. Another kind of physical change happens when matter changes from one state to another state. When water freezes and makes ice, it is still water. It has only changed its state of matter from a liquid to a solid. It has changed its appearance and shape, but it is still water. You can change the ice back into water by letting it melt. Matter looks different when it changes states, but it stays the same kind of matter. Solids like ice can change into liquids. Heat speeds up the moving particles in ice. The particles move apart. Heat melts ice and changes it to liquid water. Metals can be changed from a solid to a liquid state also. Metals must be heated to a high temperature to melt. Melting is changing from a solid state to a liquid state. -

The Summer Surface Energy Budget of the Ice-Free Area of Northern James Ross Island and Its Impact on the Ground Thermal Regime

atmosphere Article The Summer Surface Energy Budget of the Ice-Free Area of Northern James Ross Island and Its Impact on the Ground Thermal Regime Klára Ambrožová * , Filip Hrbáˇcek and Kamil Láska Department of Geography, Faculty of Science, Masaryk University, Kotláˇrská 267/2, 602 00 Brno, Czech Republic; fi[email protected] (F.H.); [email protected] (K.L.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 26 July 2020; Accepted: 15 August 2020; Published: 18 August 2020 Abstract: Despite the key role of the surface energy budget in the global climate system, such investigations are rare in Antarctica. In this study, the surface energy budget measurements from the largest ice-free area on northern James Ross Island, in Antarctica, were obtained. The components of net radiation were measured by a net radiometer, while sensible heat flux was measured by a sonic anemometer and ground heat flux by heat flux plates. The surface energy budget was compared with the rest of the Antarctic Peninsula Region and selected places in the Arctic and the impact of surface energy budget components on the ground thermal regime was examined. Mean net radiation on 2 James Ross Island during January–March 2018 reached 102.5 W m− . The main surface energy budget 2 component was the latent heat flux, while the sensible heat flux values were only 0.4 W m− lower. Mean ground heat flux was only 0.4 Wm-2, however, it was negative in 47% of January–March 2018, while it was positive in the rest of the time. The ground thermal regime was affected by surface energy budget components to a depth of 50 cm. -

Cosmic Microwave Background

1 29. Cosmic Microwave Background 29. Cosmic Microwave Background Revised August 2019 by D. Scott (U. of British Columbia) and G.F. Smoot (HKUST; Paris U.; UC Berkeley; LBNL). 29.1 Introduction The energy content in electromagnetic radiation from beyond our Galaxy is dominated by the cosmic microwave background (CMB), discovered in 1965 [1]. The spectrum of the CMB is well described by a blackbody function with T = 2.7255 K. This spectral form is a main supporting pillar of the hot Big Bang model for the Universe. The lack of any observed deviations from a 7 blackbody spectrum constrains physical processes over cosmic history at redshifts z ∼< 10 (see earlier versions of this review). Currently the key CMB observable is the angular variation in temperature (or intensity) corre- lations, and to a growing extent polarization [2–4]. Since the first detection of these anisotropies by the Cosmic Background Explorer (COBE) satellite [5], there has been intense activity to map the sky at increasing levels of sensitivity and angular resolution by ground-based and balloon-borne measurements. These were joined in 2003 by the first results from NASA’s Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP)[6], which were improved upon by analyses of data added every 2 years, culminating in the 9-year results [7]. In 2013 we had the first results [8] from the third generation CMB satellite, ESA’s Planck mission [9,10], which were enhanced by results from the 2015 Planck data release [11, 12], and then the final 2018 Planck data release [13, 14]. Additionally, CMB an- isotropies have been extended to smaller angular scales by ground-based experiments, particularly the Atacama Cosmology Telescope (ACT) [15] and the South Pole Telescope (SPT) [16]. -

Climate of Antarctica 1 Climate of Antarctica

Climate of Antarctica 1 Climate of Antarctica The climate of Antarctica is the coldest on the whole of Earth. Antarctica has the lowest naturally occurring temperature ever recorded on the surface on Earth: −89.2°C (−128.6°F) at Vostok Station. Satellites have recorded even lower temperatures, down to -93.2°C(-135.8°F). It is also extremely dry (technically a desert), averaging 166mm (6.5in) of precipitation per year. On most parts of the continent the snow rarely melts and is eventually compressed to Surface temperature of Antarctica in winter and become the glacial ice that makes up the ice sheet. Weather fronts summer from the European Centre for rarely penetrate far into the continent. Most of Antarctica has an ice Medium-Range Weather Forecasts cap climate (Köppen EF) with very cold, generally extremely dry weather. Temperature The lowest reliably measured temperature of a continuously occupied station on Earth of −89.2 °C (−128.6 °F) was on 21 July 1983 at Vostok Station.[1] For comparison, this is 10.7 °C (19.3 °F) colder than subliming dry ice (at sea level pressure). The altitude of the location is 3,900 meters (12,800 feet). The lowest recorded temperature of any location on Earth surface was −93.2 °C (−135.8 °F) at 81.8°S 59.3°E [2], which is on an unnamed Antarctic plateau between Dome A and Dome F, on August 10, 2010. The temperature was deduced from radiance measured by the Landsat 8 satellite, and discovered during a National Snow and Ice Data Center review of stored data in December, 2013. -

What Legal Framework Governs the North Pole?

What legal framework governs the North Pole? Master thesis International Law Tilburg University J.R. Mulder (ANR 865773) Supervisor: Dr M. Goodwin What legal framework governs the North Pole? Table of contents. page Introduction ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 3 Define the North Pole area North Pole area ----------------------------------------------------------------- 5 South Pole area ----------------------------------------------------------------- 6 Comparison ----------------------------------------------------------------- 7 Conflicting claims, what is the problem? -------------------------------------------------- 8 Sovereignty ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 12 Acquisition of territory -------------------------------------------------------------- 13 Sovereignty: jurisdiction and military power ------------------------------------ 14 The legal framework on the sea UN Charter --------------------------------------------------------------------------- 15 Customary International Law ------------------------------------------------------ 15 General Principles ------------------------------------------------------------------- 16 Jurisprudence ------------------------------------------------------------------------ 17 UNCLOS ----------------------------------------------------------------------------- 17 Schematic overview of zones into the sea ---------------------------------------- 21 The legal framework applied to the North Pole -

The Temperature of the Cosmic Microwave Background at 10 Ghz D

The Astrophysical Journal, 612:86–95, 2004 September 1 # 2004. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in U.S.A. THE TEMPERATURE OF THE COSMIC MICROWAVE BACKGROUND AT 10 GHZ D. J. Fixsen,1 A. Kogut,2 S. Levin,3 M. Limon,1 P. Lubin,4 P. Mirel,1 M. Seiffert,3 and E. Wollack2 Received 2004 February 23; accepted 2004 April 14 ABSTRACT We report the results of an effort to measure the low-frequency portion of the spectrum of the cosmic microwave background (CMB) radiation, using a balloon-borne instrument called the Absolute Radiometer for Cosmology, Astrophysics, and Diffuse Emission (ARCADE). These measurements are to search for deviations from a thermal spectrum that are expected to exist in the CMB as a result of various processes in the early universe. The radiometric temperature was measured at 10 and 30 GHz using a cryogenic open-aperture instrument with no emissive windows. An external blackbody calibrator provides an in situ reference. Systematic errors were greatly reduced by using differential radiometers and cooling all critical components to physical temperatures approxi- mating the antenna temperature of the sky. A linear model is used to compare the radiometer output to a set of thermometers on the instrument. The unmodeled residualsarelessthan50mKpeaktopeakwithaweightedrms of 6 mK. Small corrections are made for the residual emission from the flight train, atmosphere, and foreground Galactic emission. The measured radiometric temperature of the CMB is 2:721 Æ 0:010 K at 10 GHz and 2:694 Æ 0:032 K at 30 GHz. Subject headinggs: cosmic microwave background — cosmology: observations 1.