Mosques in the Malay World As Cosmopolitan Spaces

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Canossa Connects a Quarterly Newsletter for Parents of Canossa Catholic Primary School Volume 3 2019

Canossa Connects A Quarterly Newsletter for Parents of Canossa Catholic Primary School Volume 3 2019 Please access our school website for this issue of Canossa Connects with photographs. A Note from the Editor… In this third issue, be inspired by our pupils’ abundant energy and enthusiasm for life and learning as you read about how they embraced exciting, new adventures both on the home front and overseas. Our pupils proudly represented Singapore and the school as ambassadors, in their many interactions with people from other schools and countries, while on school trips, learning journeys, co-curricular activities and competitions. High-spirited, they fervently supported their houses during Sports and Games Day while humbly demonstrating admirable sportsmanship. They sang in one voice, songs of love and loyalty for the country as they celebrated Singapore’s bicentennial together. Our Canossians sons and daughters truly did themselves, their families, their school and their nation proud by showing a deep sense of rootedness and loyalty! Mrs Michele Ho COMMITMENT “The greatest gift one person can give another is time.” - St. Magdalene of Canossa P6 Motivational Talk by CCPS Junior Alumni Members Having been invited to deliver a motivational talk on 1 August to our graduating batch of pupils, Genevieve Yen rose to the challenge. Her passion to inspire her juniors was moving; she had rushed down after her enrichment lessons just so that she could give back to her alma mater, which she felt had been such an important part of her growing years. Our pupils were truly impressed by her boundless energy and enthusiasm. -

In Syi'ir Tanpa Waton As One of an Alternative Effort Or Academic Resolutions to Evercome the Problems Mentioned Above

Teosofia: Indonesian Journal of Islamic Mysticism, Vol. 7, No. 2, 2018, pp. 115-136 e-ISSN: 2540-8186; p-ISSN: 2302-8017 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.21580/tos.v7i2.4405 THE SPIRITUAL MEANING OF SULUK IN SYI’IR TANPA WATON Siti Maslahah UIN Sunan Kalijaga [email protected] Abstract: Syi’ir Tanpa Waton, a work of KH Mohammad Nizam As-shofa, is a sufi poem. It is a cultural endeavor to response the modern problems of Muslims who easily judge others infidels without realizing their own infidelity. This poem is used as a closing recitation of Reboan Agung (Islamic regular study forum of Muslim conducted in every Wednesday night learning the book of Jamī’ al-uṣul fi al-uliyā’ the work of Shaykh Ahmad Dhiya 'uddin Musthofa Al-Kamisykhonawi) and the book of Al-Fatḥurrabbani wa al-Faiḍurrahmani the work of Shaykh Abdul Qadir al-Jilani. The forum took place at Islamic boarding school of Ahlus-Shofa Wal Wafa Sidoarjo, East Java. This research is inspired by spiritual emptiness caused by the modernization and the shallow understanding of Islamic teachings. Islam is studied and practiced at the level of shari'a without deepening it into higher stages of sufism i.e. tariqa, haqiqa and even marifa. This study employs content analysis and qualitative approach aims at analyzing the message or moral values contained in the literature. Then, I classifies basic thoughts into some themes and selects these themes to find the central idea of the text. Substantively, the verses were structurely written ranging from understanding comprehensively the teachings of Islam, teachings self-awareness, the teachings of social piety (humanism) and the teachings of Sufism namely suluk practice. -

The Assesment of Measurement Application for Timber

i THE ASSESMENT OF MEASUREMENT APPLICATION FOR TIMBER TRADITIONAL MALAY HOUSE YUSNANI BT HUSLI A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Bachelor of Civil Engineering Faculty of Civil Engineering and Earth Resources University Malaysia Pahang MEI 2011 ii “I hereby declare that I have read this thesis and in my opinion this thesis is sufficient in terms of scope and quality for the award of the degree of Bachelor of Civil Engineering” Signature : ……………………………. Name of Supervisor : MR MOHAMMAD AFFENDY BIN OMARDIN Date : 4 MEI 2011 iii “I hereby declare that I have read this thesis and in my opinion this thesis is sufficient in terms of scope and quality for the award of the Degree of Civil Engineering & Earth Resources”. I also certify that the work described here is entirely my own except for excerpts and summaries whose sources are appropriately cited in the references.” Signature :………………………… Name : YUSNANI BT HUSLI Date : 4 MEI 2011 iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Firstly, thanks to Allah S.W.T., my lovely family and friends who has inspired me to accomplished this final year project as a requirement to graduate and acquire a bachelor degree in civil engineering from University Malaysia Pahang (UMP). And do not forget also to thanks a lot to my adored and beloved supervisor MOHAMMAD AFFENDY BIN OMARDIN. During this final year project, we face lots of impediment and many meaningful challenges. There are lots of lacks and flaws due to the first time exposure towards this project. With his present teachings and guidance, has made my final year project progress gone smooth and recognized by the university. -

E-Warisan SENIBINA Towards a Collaborative Architectural Virtual Heritage Experience

e-Warisan SENIBINA Towards a collaborative architectural virtual heritage experience Ahmad Rafi1, Azhar Salleh2, Avijit Paul3, Reza Maulana4, Faisal Athar5, Gatya Pratiniyata6 1,2,3Multimedia University, Cyberjaya, Malaysia, 4,5,6MMUCreativista Sdn Bhd, Multimedia University, Malaysia 1,2,3http://www.mmu.edu.my, 4,5,6http://www.ewarisan.com [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. [email protected] Abstract. This research introduces the concepts of virtual heritage in the field of architecture. It then continues with the fundamentals of virtual heritage (VH) metadata structure adopted from the UNESCO guidelines. The key highlights to the content of e-Warisan SENIBINA will be demonstrated via techniques to reconstruct heritage buildings towards a collaborative architectural virtual heritage experience as closely to originally design features. The virtual re- construction will be based on the techniques suggested by the research team tested earlier in a smaller scale of advanced lighting technique for virtual heritage representations. This research will suggest (1) content preparation for creating collaborative architectural heritage, (2) effective low-polygon modelling solutions that incorporate global illumination (GI) lighting for real-time simulation and (3) texturing techniques to accommodate reasonable detailing and give the essence of the VH. Keywords. Simulation; virtual heritage; virtual reality; collaborative environment; realistic lighting. Introduction historic, artistic, religious and cultural significance and to deliver the results openly to a global audience Virtual reality technology has opened up possibili- in such a way as to provide formative educational ex- ties of techniques and effective ways for research, periences through electronic manipulations of time especially in the field of design, architecture, inter- and space. -

The Influence of Hindu, Buddhist, and Chinese Culture on the Shapes of Gebyog of the Javenese Traditional Houses

Arts and Design Studies www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-6061 (Paper) ISSN 2225-059X (Online) Vol.79, 2019 The Influence of Hindu, Buddhist, and Chinese Culture on the Shapes of Gebyog of the Javenese Traditional Houses Joko Budiwiyanto 1 Dharsono 2 Sri Hastanto 2 Titis S. Pitana 3 Abstract Gebyog is a traditional Javanese house wall made of wood with a particular pattern. The shape of Javanese houses and gebyog develop over periods of culture and government until today. The shapes of gebyog are greatly influenced by various culture, such as Hindu, Buddhist, Islamic, and Chinese. The Hindu and Buddhist influences of are evident in the shapes of the ornaments and their meanings. The Chinese influence through Islamic culture developing in the archipelago is strong, mainly in terms of the gebyog patterns, wood construction techniques, ornaments, and coloring techniques. The nuance has been felt in the era of Majapahit, Demak, Mataram and at present. The use of ganja mayangkara in Javanese houses of the Majapahit era, the use of Chinese-style gunungan ornaments at the entrance to the Sunan Giri tomb, the saka guru construction technique of Demak mosque, the Kudusnese and Jeparanese gebyog motifs, and the shape of the gebyog patangaring of the house. Keywords: Hindu-Buddhist influence, Chinese influence, the shape of gebyog , Javanese house. DOI : 10.7176/ADS/79-09 Publication date: December 31st 2019 I. INTRODUCTION Gebyog , according to the Javanese-Indonesian Dictionary, is generally construed as a wooden wall. In the context of this study, gebyog is a wooden wall in a Javanese house with a particular pattern. -

Isfm 4 Isbn 978-979-792-665-6

December 3, 2015 The Grand Elite Hotel, Pekanbaru, INDONESIA ISFM 4 ISBN 978-979-792-665-6 The 4th International Seminar of Fisheries and Marine Science 2015 Strengthening Science and Technology Towards the Development of Blue Economy December 3, 2015 Grand Elite Hotel Pekanbaru-INDONESIA ISBN 978-979-792-665-6 International Proceeding Committees Prof. Dr. Ir. Bintal Amin, M.Sc Dr. Ir. Syofyan Husein Siregar, M.Sc Ir. Mulyadi, M.Phil Ir. Ridwan Manda Putra, M.Si Dr. Windarti, M.Sc Dr. Victor Amrifo, S.Pi., M.Si Dr. Ir. Henni Syawal, M.Si Dr. Rahman Karnila, S.Pi., M.Si Ronald Mangasi Hutauruk, S.T., M.T. Benny Heltonika, S.Pi., M.Si Dr. Ir. Efriyeldi, M.Sc Dr. Ir. Mery Sukmiwati, M.Si Dr. Ir. Joko Samiaji, M.Sc Dr. Ir. Eni Sumiarsih, M.Sc Dr. T. Ersti Yulika Sari, S.Pi., M.Si Nur Asiah, S.Pi., M.Si Dr. Ir. Deni Efizon, M.Sc Ir. Ridar Hendri, M.Si Tri Gunawan, S.Sos Masmulyana Putra Editor: Ronald Mangasi Hutauruk, S. T., M. T. The 4th International Seminar on Fisheries and Marine Science, December 3, 2015 ii Pekanbaru-INDONESIA ISBN 978-979-792-665-6 International Proceeding Preface Aquatic ecosystem in general has been recognized as a mega ecosystem that is needed to be conserved. Through science and technology, this ecosystem might be developed to enable it to support the prosperity of a nation. To support this, the International Seminar on Fisheries and Marine Science (ISFM) 2015 held in Pekanbaru took its theme of “strengthening science and technology toward the development of blue economy”. -

THE ROLE of CHENG HO MOSQUE the New Silk Road, Indonesia

DOI: 10.15642/JIIS.2014.8.1.23Islamic Cultural Identity-38 THE ROLE OF CHENG HO MOSQUE The New Silk Road, Indonesia-China Relations in Islamic Cultural Identity Choirul Mahfud Institute for Religions and Social Studies, Surabaya – Indonesia | [email protected] Abstract: This article discusses the role of the Cheng Ho mosque in developing cultural, social, educational and religious aspects between the Chinese and non-Chinese in Indonesia and in strengthening the best relationship internationally between Indonesia and China. The Cheng Ho Mosque is one of the ethnic Chinese cultural identities in contemporary Indonesia. Currently, it is not only as a place of worship for Chinese Islam, but also as a religious tourism destination as well as new media to learn about Islamic Chinese cultures in Indonesia. In addition, Cheng Ho mosque is also beginning to be understood as the “new silk road”, because it assumed that it has an important role in fostering a harmonious relationship between the Indonesian government and China. It can be seen from the establishment of Cheng Ho mosques in a number of regions in Indonesia. In this context, this article describes what the contributions and implications of the Cheng Ho mosque as the new silk road in fostering bilateral relations between Indonesia and China, especially in Islamic cultural identity. Keywords: the Cheng Ho Mosque, Chinese muslim, Cultural Identity Introduction The Cheng Ho Mosque is a part of interesting topics on Chinese Muslim-Indonesian identities in Indonesia. Many researchers from all countries pay attention to this Mosque from different views. Hew Wai Weng in his doctoral research at ANU Canberra on “Chinese-style mosques in Indonesia” highlighted the unique architecture of the JOURNAL OF INDONESIAN ISLAM Volume 08, Number 01, June 2014 23 Choirul Machfud Cheng Ho Mosque in Surabaya, which has a Chinese style. -

Religious Harmony in Singapore: Spaces, Practices and Communities 469190 789811 9 Lee Hsien Loong, Prime Minister of Singapore

Religious Harmony in Singapore: Spaces, Practices and Communities Inter-religious harmony is critical for Singapore’s liveability as a densely populated, multi-cultural city-state. In today’s STUDIES URBAN SYSTEMS world where there is increasing polarisation in issues of race and religion, Singapore is a good example of harmonious existence between diverse places of worship and religious practices. This has been achieved through careful planning, governance and multi-stakeholder efforts, and underpinned by principles such as having a culture of integrity and innovating systematically. Through archival research and interviews with urban pioneers and experts, Religious Harmony in Singapore: Spaces, Practices and Communities documents the planning and governance of religious harmony in Singapore from pre-independence till the present and Communities Practices Spaces, Religious Harmony in Singapore: day, with a focus on places of worship and religious practices. Religious Harmony “Singapore must treasure the racial and religious harmony that it enjoys…We worked long and hard to arrive here, and we must in Singapore: work even harder to preserve this peace for future generations.” Lee Hsien Loong, Prime Minister of Singapore. Spaces, Practices and Communities 9 789811 469190 Religious Harmony in Singapore: Spaces, Practices and Communities Urban Systems Studies Books Water: From Scarce Resource to National Asset Transport: Overcoming Constraints, Sustaining Mobility Industrial Infrastructure: Growing in Tandem with the Economy Sustainable Environment: -

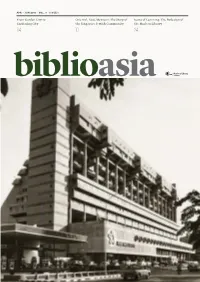

Apr–Jun 2013

VOL. 9 iSSUe 1 FEATURE APr – jUn 2013 · vOL. 9 · iSSUe 1 From Garden City to Oriental, Utai, Mexican: The Story of Icons of Learning: The Redesign of Gardening City the Singapore Jewish Community the Modern Library 04 10 24 01 BIBLIOASIA APR –JUN 2013 Director’s Column Editorial & Production “A Room of One’s Own”, Virginia Woolf’s 1929 essay, argues for the place of women in Managing Editor: Stephanie Pee Editorial Support: Sharon Koh, the literary tradition. The title also makes for an apt underlying theme of this issue Masamah Ahmad, Francis Dorai of BiblioAsia, which explores finding one’s place and space in Singapore. Contributors: Benjamin Towell, With 5.3 million people living in an area of 710 square kilometres, intriguing Bernice Ang, Dan Koh, Joanna Tan, solutions in response to finding space can emerge from sheer necessity. This Juffri Supa’at, Justin Zhuang, Liyana Taha, issue, we celebrate the built environment: the skyscrapers, mosques, synagogues, Noorashikin binte Zulkifli, and of course, libraries, from which stories of dialogue, strife, ambition and Siti Hazariah Abu Bakar, Ten Leu-Jiun Design & Print: Relay Room, Times Printers tradition come through even as each community attempts to find a space of its own and leave a distinct mark on where it has been and hopes to thrive. Please direct all correspondence to: A sense of sanctuary comes to mind in the hubbub of an increasingly densely National Library Board populated city. In Justin Zhuang’s article, “From Garden City to Gardening City”, he 100 Victoria Street #14-01 explores the preservation and the development of the green lungs of Sungei Buloh, National Library Building Singapore 188064 Chek Jawa and, recently, the Rail Corridor, as breathing spaces of the city. -

Kebudayaan Megalitik Di Sulawesi Selatan Dan Hubungannya Dengan Asia Tenggara

KEBUDAYAAN MEGALITIK DI SULAWESI SELATAN DAN HUBUNGANNYA DENGAN ASIA TENGGARA HASANUDDIN UNIVERSITI SAINS MALAYSIA 2015 KEBUDAYAAN MEGALITIK DI SULAWESI SELATAN DAN HUBUNGANNYA DENGAN ASIA TENGGARA Oleh HASANUDDIN Tesis yang diserahkan untuk memenuhi keperluan bagi Ijazah Doktor Falsafah SEPTEMBER 2015 PENGHARGAAN Syukur Alhamdulillah penulis ucapkan kepada Allah SWT kerana dengan curahan rahmat dan hidayah-Nya tesis ini dapat diselesaikan. Salam dan selawat disampaikan kepada Nabi Muhammad SAW dan para sahabat sebagai suri tauladan yang baik dalam mengarungi kehidupan ini.Tesis ini diselesaikan dengan baik oleh kerana bimbingan, bantuan, sokongan, dan kerjasama yang baik dari beberapa pihak dan individu. Oleh kerana itu, penulis merakamkan ucapan terima kasih yang tidak terhingga kepada Profesor Dr. Stephen Chia Ming Soon, Timbalan Pengarah Pusat Penyelidikan Arkeologi Global, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Pulau Pinang sebagai penyelia penulis. Tanpa pernah merasa jemu beliau membimbing, dan memberi tunjuk ajar kepada penulis sepanjang penyelidikan sehingga penyelesaian tesis ini. Beliau telah membantu penulis dalam kerja lapangan, pentarikhan dan membantu dalam hal kewangan.Terima kasih tidak terhingga juga disampaikan kepada Profesor Dato’ Dr. Mohd. Mokhtar bin Saidin, Pengarah Pusat Penyelidikan Arkeologi Global, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Pulau Pinang yang telah memberikan kesempatan kepada penulis untuk menjalankan kajian di Pusat Penyelidikan Arkeologi Global di Pulau Pinang Malaysia. Beliau sentiasa memberikan nasihat, dorongan dan semangat dalam melakukan kajian ini. Penulis juga mengucapkan terima kasih kepada kakitangan Institut Pengajian Siswazah, Universiti Sains Malaysia yang sentiasa memberikan bimbingan terutamanya dekan serta kakitangan institut. Penulis merakamkan setinggi-tinggi terima kasih kepada kakitangan akademik Pusat Penyelidikan Arkeologi Global, Universiti Sains Malaysia yang sentiasa bersedia menghulurkan bantuan dan buah fikiran terutamanya kepada Dr. -

Evaluation of Quality of Building Maintenance in Ampel Mosque Surabaya

Wawasan: Jurnal Ilmiah Agama dan Sosial Budaya 3, 2 (2018): 216-230 Website: journal.uinsgd.ac.id/index.php/jw ISSN 2502-3489 (online) ISSN 2527-3213 (print) EVALUATION OF QUALITY OF BUILDING MAINTENANCE IN AMPEL MOSQUE SURABAYA Agung Sedayu UIN Maulana Malik Ibrahim Malang Jln.Gajayana 50 Malang, Jawa Timur, Indonesia E-mail: [email protected] _________________________ Abstract The Ampel Mosque Surabaya East Java Indonesia is a historic mosque that became one of the centers of the spread of Islam in Java by Sunan Ampel. The mosque is a historic site to get attention in care and maintenance on the physical components of the building to prevent the occurrence of damage. This study aims to evaluate the quality of maintenance of Ampel Surabaya mosque building. This study considers social-culture aspects and technical aspects as an instrument to support building maintenance and reliability enhancement. The quality of the maintenance affects the reliability of mosque building construction. The evaluation is done by considering the user's perception of the facility to worship in the mosque of Ampel. The method used is Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). The result of the research shows four variables that make up the model namely: Structural Component, Architectural Component as exogenous manifest variable 2, Quality Maintenance, and Construction Reliability. Relationships between variables indicate a strong level of significance. The path diagram model obtained is explained that the variability of Maintenance Quality is explained by Structural Component and Architectural Component of 81.6%, while Construction Reliability can be explained by Structural Component, Maintenance Quality, and Architectural Component variability of 87.2%. -

The Spreading of Vernacular Architecture at the Riverways Of

Indonesian Journal of Geography Vol. 5151 No.No. 2,3, August December 2019 2019 (199-206) (385 - 392) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.22146/ijg.44914http://dx.doi.org/ 10.22146/ijg.43923 RESEARCH ARTICLE Thee Eect Spreading of Baseline of Vernacular Component Architecture Correlation at the on theRiverways Design of of South GNSS Sumatra, IndonesiaNetwork Conguration for Sermo Reservoir Deformation Monitoring Yulaikhah1,3, Subagyo Pramumijoyo2, Nurrohmat Widjajanti3 Maya Fitri Oktarini 1Ph.D. Student, Doctoral Study Program of Geomatics Engineering, Department of Geodetic Engineering, Universitas Sriwijaya, Palembang, Indonesia Faculty of Engineering, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Indonesia 2Department of Geological Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Indonesia 3Department of Geodetic Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta, Indonesia Received: 2019-03-13 Abstract: The development of past settlements was supported by riverways connecting many Accepted: 2019-12-09 regions with ethnic diversities. Inter-ethnic dissemination and contact created new cultural Received: 2019-05-18 Abstract e condition of the geological structure in the surrounding Sermo reservoir shows combinations. In the southern part of Sumatra, there are two types of stilt houses: highland Accepted: 2019-07-29 that there is a fault crossing the reservoir. Deformation monitoring of that fault has been carried architecture and lowland architecture. Both architectures are developed by different ethnic out by conducting GNSS campaigns at 15 monitoring stations simultaneously. However, those Keywords: groups spread along different riverways. This study focuses on identifying and analyzing the Vernacular Architecture, campaigns were not well designed. With such a design, it took many instruments and spent influence of the riverway in the typology of the vernacular stilt house.