The LOCH: Heaven’S Lake

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ancient Crocodile Relative Likely Food Source for Titanoboa 2 February 2010, by Bill Kanapaux

Ancient crocodile relative likely food source for Titanoboa 2 February 2010, by Bill Kanapaux "We're starting to flesh out the fauna that we have from there," said lead author Alex Hastings, a graduate student at the Florida Museum and UF's department of geological sciences. Specimens used in the study show the new species, named Cerrejonisuchus improcerus, grew only 6 to 7 feet long, making it easy prey for Titanoboa. Its scientific name means small crocodile from Cerrejon. The findings follow another study by researchers at UF and the Smithsonian providing the first reliable evidence of what Neotropical rainforests looked like 60 million years ago. While Cerrejonisuchus is not directly related to On Feb. 1, 2010, Alex Hastings, a graduate student at modern crocodiles, it played an important role in UF’s Florida Museum of Natural History, measures a the early evolution of South American rainforest jaw fragment from an ancient crocodile that lived 60 ecosystems, said Jonathan Bloch, a Florida million years ago. The fossil came from the same site in Museum vertebrate paleontologist and associate Colombia as fossils of Titanoboa, indicating the crocodile curator. was a likely food source for the giant snake. "Clearly this new fossil would have been part of the food-chain, both as predator and prey," said Bloch, who co-led the fossil-hunting expeditions to (PhysOrg.com) -- A 60-million-year-old relative of Cerrejon with Smithsonian paleobotanist Carlos crocodiles described this week by University of Jaramillo. "Giant snakes today are known to eat Florida researchers in the Journal of Vertebrate crocodylians, and it is not much of a reach to say Paleontology was likely a food source for Cerrejonisuchus would have been a frequent meal Titanoboa, the largest snake the world has ever for Titanoboa. -

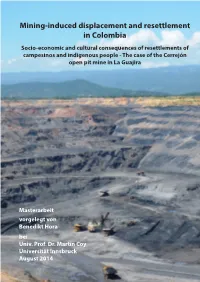

Mining-Induced Displacement and Resettlement in Colombia

Mining-induced displacement and resettlement in Colombia Socio-economic and cultural consequences of resettlements of campesinos and indigenous people - The case of the Cerrejón open pit mine in La Guajira Masterarbeit vorgelegt von Benedikt Hora bei Univ. Prof. Dr. Martin Coy Universität Innsbruck August 2014 Masterarbeit Mining-induced displacement and resettlement in Colombia Socio-economic and cultural consequences of resettlements of campesinos and indigenous people – The case of the Cerrejón open pit mine in La Guajira Verfasser Benedikt Hora B.Sc. Angestrebter akademischer Grad Master of Science (M.Sc.) eingereicht bei Herrn Univ. Prof. Dr. Martin Coy Institut für Geographie Fakultät für Geo- und Atmosphärenwissenschaften an der Leopold-Franzens-Universität Innsbruck Eidesstattliche Erklärung Ich erkläre hiermit an Eides statt durch meine eigenhändige Unterschrift, dass ich die vorliegende Arbeit selbstständig verfasst und keine anderen als die angegebene Quellen und Hilfsmittel verwendet habe. Alle Stellen, die wörtlich oder inhaltlich an den angegebenen Quellen entnommen wurde, sind als solche kenntlich gemacht. Die vorliegende Arbeit wurde bisher in gleicher oder ähnlicher Form noch nicht als Magister- /Master-/Diplomarbeit/Dissertation eingereicht. _______________________________ Innsbruck, August 2014 Unterschrift Contents CONTENTS Contents ................................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Preface -

Systematic Revision of the Early Miocene Fossil Pseudoepicrates

Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2018, XX, 1–18. With 10 figures. Systematic revision of the early Miocene fossil Pseudoepicrates (Serpentes: Boidae): implications for the evolution and historical biogeography of the West Indian boid snakes (Chilabothrus) SILVIO ONARY1* AND ANNIE S. HSIOU1 1Departamento de Biologia, Laboratório de Paleontologia de Ribeirão Preto, Faculdade de Filosofia Ciências e Letras de Ribeirão Preto, Universidade de São Paulo, Ribeirão Preto, São Paulo, Brazil. Received 20 June 2017; revised 28 November 2017; accepted for publication 23 December 2017 The taxonomy of the early Miocene genus Pseudoepicrates is controversial. Originally interpreted as the viperid Neurodromicus, subsequent work deemed the material to represent an extinct boid, Pseudoepicrates stanolseni. However, more recent work considered Pseudoepicrates to be a synonym of the extant Boa constrictor. Due to these conflicting interpretations, we provide a revision of the systematic affinities of P. stanolseni. This redescription was based on the first-hand analysis of all material of Pseudoepicrates, together with the comparison of extant boids. Our findings suggest that, in addition to being an invalid taxon, ‘Pseudoepicrates’ cannot be referred to B. constric- tor. Instead, the extant Chilabothrus is here regarded as the most cogent generic assignment, with Chilabothrus stanolseni comb. nov. proposed for the extinct species. The referral of this material to Chilabothrus suggests that the genus originated as early as ~18.5 Mya. The revised history of this record has interesting implications for our understanding of the early divergence of the group. The presence of Chilabothrus in the early Miocene of Florida supports biogeographical hypotheses, which suggest that the genus reached the West Indian island complex around 22 Mya, dispersing into the North American territory by at least 18.5 Mya. -

Reptiles Fósiles De Colombia Un Aporte Al Conocimiento Y a La Enseñanza Del Patrimonio Paleontológico Del País

Reptiles Fósiles de Colombia Un aporte al conocimiento y a la enseñanza del patrimonio paleontológico del país Luis Gonzalo Ortiz-Pabón Universidad Pedagógica Nacional Facultad de Ciencia y tecnología Departamento de biología Bogotá D.C. 2020 Reptiles Fósiles de Colombia Un aporte al conocimiento y a la enseñanza del patrimonio paleontológico del país Luis Gonzalo Ortiz-Pabón Trabajo presentado como requisito para optar por el título de: Licenciado en Biología Directora: Heidy Paola Jiménez Medina MSc. Línea de Investigación: Educación en Ciencias y formación Ambiental Grupo de Investigación: Educación en Ciencias, Ambiente y Diversidad Universidad Pedagógica Nacional Facultad de Ciencia y tecnología Departamento de biología Bogotá D.C. 2020 Dedicatoria A mi mami, quien ha estado acompañándome y apoyándome en muchos de los momentos definitivos de mi vida, además de la deuda que tengo con ella desde 2008. “La ciencia no es una persecución despiadada de información objetiva. Es una actividad humana creativa, sus genios actúan más como artistas que como procesadores de información” Stephen J. Gould Agradecimientos En primera instancia agradezco a todos los maestros y maestras que fueron parte esencial de mi formación académica. Agradecimiento especial al Ilustrador y colega Marco Salazar por su aporte gráfico a la construcción del libro Reptiles Fósiles de Colombia, a Oscar Hernández y a Galdra Films por su valioso aporte en la diagramación y edición del libro, a Heidy Jiménez quien fue mi directora y guía en el desarrollo de este trabajo y a Vanessa Robles, quien estuvo acompañando la revisión del libro y este escrito, además del apoyo emocional brindado en todo momento. -

THE FOSSIL RECORD of TURTLES in COLOMBIA; a REVIEW of the DISCOVERIES, RESEARCH and FUTURE CHALLENGES Acta Biológica Colombiana, Vol

Acta Biológica Colombiana ISSN: 0120-548X [email protected] Universidad Nacional de Colombia Sede Bogotá Colombia CADENA, EDWIN A THE FOSSIL RECORD OF TURTLES IN COLOMBIA; A REVIEW OF THE DISCOVERIES, RESEARCH AND FUTURE CHALLENGES Acta Biológica Colombiana, vol. 19, núm. 3, septiembre-diciembre, 2014, pp. 333-339 Universidad Nacional de Colombia Sede Bogotá Bogotá, Colombia Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=319031647001 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative SEDE BOGOTÁ ACTA BIOLÓGICA COLOMBIANA FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS DEPARTAMENTO DE BIOLOGÍA ARTÍCULO DE REVISIÓN THE FOSSIL RECORD OF TURTLES IN COLOMBIA; A REVIEW OF THE DISCOVERIES, RESEARCH AND FUTURE CHALLENGES El registro fósil de las tortugas en Colombia; una revisión de los descubrimientos, investigaciones y futuros desafíos EDWIN A CADENA1; Ph. D. 1 Senckenberg Museum, Dept. of Palaeoanthropology and Messel Research, 603025 Frankfurt, Germany. [email protected] Received 21st February 2014, first decision 21st April de 2014, accepted 1st May 2014. Citation / Citar este artículo como: CADENA EA. The fossil record of turtles in Colombia: a review of the discoveries, research and future challenges. Acta biol. Colomb. 2014;19(3):333-339. ABSTRACT This is a review article on the fossil record of turtles in Colombia that includes: the early Cretaceous turtles from Zapatoca and Villa de Leyva localities; the giant turtles from the Paleocene Cerrejón and Calenturitas Coal Mines; the early Miocene, earliest record of Chelus from Pubenza, Cundinamarca; the early to late Miocene large podocnemids, chelids and testudinids from Castilletes, Alta Guajira and La Venta; and the small late Pleistocene kinosternids from Pubenza, Cundinamarca. -

X Congreso Argentino De Paleontología Y Bioestratigrafía VII Congreso Latinoamericano De Paleontología La Plata, Argentina - Septiembre De 2010

X Congreso Argentino de Paleontología y Bioestratigrafía VII Congreso Latinoamericano de Paleontología La Plata, Argentina - Septiembre de 2010 Financian Auspician 1 X Congreso Argentino de Paleontología y Bioestratigrafía VII Congreso Latinoamericano de Paleontología La Plata, Argentina - Septiembre de 2010 2 X Congreso Argentino de Paleontología y Bioestratigrafía VII Congreso Latinoamericano de Paleontología La Plata, Argentina - Septiembre de 2010 3 X Congreso Argentino de Paleontología y Bioestratigrafía VII Congreso Latinoamericano de Paleontología La Plata, Argentina - Septiembre de 2010 X Congreso Argentino de Paleontología y Bioestratigrafía y VII Congreso Latinoamericano de Paleontología Resúmenes/coordinado por Sara Ballent ; Analia Artabe ; Franco Tortello. 1a ed. - La Plata: Museo de la Plata; Museo de la Plata, 2010. 238 p. + CD-ROM; 28x20 cm. ISBN 978-987-95849-7-2 1. Paleontología. 2. Bioestratigrafía. I. Ballent, Sara , coord. II. Artabe, Analia, coord. III. Tortello, Franco, coord. CDD 560 Fecha de catalogación: 27/08/2010 4 X Congreso Argentino de Paleontología y Bioestratigrafía VII Congreso Latinoamericano de Paleontología La Plata, Argentina - Septiembre de 2010 X Congreso Argentino de Paleontología y Bioestratigrafía VII Congreso Latinoamericano de Paleontología Declarado de Interés Municipal, La Plata (Decreto N° 1158) 5 X Congreso Argentino de Paleontología y Bioestratigrafía VII Congreso Latinoamericano de Paleontología La Plata, Argentina - Septiembre de 2010 6 X Congreso Argentino de Paleontología y Bioestratigrafía VII Congreso Latinoamericano de Paleontología La Plata, Argentina - Septiembre de 2010 X Congreso Argentino de Paleontología y Bioestratigrafía VII Congreso Latinoamericano de Paleontología Prólogo Una vez más el Congreso Argentino de Paleontología y Bioestratigrafía y el Congreso Latino- americano de Paleontología se realizan de manera conjunta. -

Downloaded From

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2020 The anatomy, paleobiology, and evolutionary relationships of the largest extinct side-necked turtle Cadena, E-A ; Scheyer, T M ; Carrillo-Briceño, J D ; Sánchez, R ; Aguilera-Socorro, O A ; Vanegas, A ; Pardo, M ; Hansen, D M ; Sánchez-Villagra, M R Abstract: Despite being among the largest turtles that ever lived, the biology and systematics of Stupen- demys geographicus remain largely unknown because of scant, fragmentary finds. We describe exceptional specimens and new localities of S. geographicus from the Miocene of Venezuela and Colombia. We doc- ument the largest shell reported for any extant or extinct turtle, with a carapace length of 2.40 m and estimated mass of 1.145 kg, almost 100 times the size of its closest living relative, the Amazon river turtle Peltocephalus dumerilianus, and twice that of the largest extant turtle, the marine leatherback Dermochelys coriacea. The new specimens greatly increase knowledge of the biology and evolution of this iconic species. Our findings suggest the existence of a single giant turtle species across the northern Neotropics, but with two shell morphotypes, suggestive of sexual dimorphism. Bite marks and punctured bones indicate interactions with large caimans that also inhabited the northern Neotropics. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aay4593 Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-184939 Journal Article Published Version The following work is licensed under a Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) License. -

A New Longirostrine Dyrosaurid

[Palaeontology, Vol. 54, Part 5, 2011, pp. 1095–1116] A NEW LONGIROSTRINE DYROSAURID (CROCODYLOMORPHA, MESOEUCROCODYLIA) FROM THE PALEOCENE OF NORTH-EASTERN COLOMBIA: BIOGEOGRAPHIC AND BEHAVIOURAL IMPLICATIONS FOR NEW-WORLD DYROSAURIDAE by ALEXANDER K. HASTINGS1, JONATHAN I. BLOCH1 and CARLOS A. JARAMILLO2 1Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32611, USA; e-mails: akh@ufl.edu, jbloch@flmnh.ufl.edu 2Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, Box 0843-03092 and #8232, Balboa-Ancon, Panama; e-mail: [email protected] Typescript received 19 March 2010; accepted in revised form 21 December 2010 Abstract: Fossils of dyrosaurid crocodyliforms are limited rosaurids. Results from a cladistic analysis of Dyrosauridae, in South America, with only three previously diagnosed taxa using 82 primarily cranial and mandibular characters, sup- including the short-snouted Cerrejonisuchus improcerus from port an unresolved relationship between A. guajiraensis and a the Paleocene Cerrejo´n Formation of north-eastern Colom- combination of New- and Old-World dyrosaurids including bia. Here we describe a second dyrosaurid from the Cerrejo´n Hyposaurus rogersii, Congosaurus bequaerti, Atlantosuchus Formation, Acherontisuchus guajiraensis gen. et sp. nov., coupatezi, Guarinisuchus munizi, Rhabdognathus keiniensis based on three partial mandibles, maxillary fragments, teeth, and Rhabdognathus aslerensis. Our results are consistent with and referred postcrania. The mandible has a reduced seventh an African origin for Dyrosauridae with multiple dispersals alveolus and laterally depressed retroarticular process, both into the New World during the Late Cretaceous and a transi- diagnostic characteristics of Dyrosauridae. Acherontisuchus tion from marine habitats in ancestral taxa to more fluvial guajiraensis is distinct among known dyrosaurids in having a habitats in more derived taxa. -

COLOMBIANA De Ciencias Exactas, Físicas Y Naturales

ISSN 0370-3908 eISSN 2382-4980 REVISTA DE LA ACADEMIA COLOMBIANA de Ciencias Exactas, Físicas y Naturales Vol. 42 • Número 164 • Págs. 161-300 • Julio-Septiembre de 2018 • Bogotá - Colombia ISSN 0370-3908 eISSN 2382-4980 Academia Colombiana de Ciencias Exactas, Físicas y Naturales Vol. 42 • Número 164 • Págs. 161-300 • Julio-Septiembre de 2018 • Bogotá - Colombia Comité editorial Editora Elizabeth Castañeda, Ph. D. Instituto Nacional de Salud, Bogotá, Colombia Editores asociados Ciencias Biomédicas Fernando Marmolejo-Ramos, Ph. D. Universidad de Adelaide, Adelaide, Australia Luis Fernando García, M.D., M.Sc. Universidad de Antioquia, Medellin, Colombia Ciencias Físicas Gustavo Adolfo Vallejo, Ph. D. Pedro Fernández de Córdoba, Ph. D. Universidad del Tolima, Ibagué, Colombia Universidad Politécnica de Valencia, España Luis Caraballo, Ph. D. Diógenes Campos Romero, Dr. rer. nat. Universidad de Cartagena, Cartagena, Colombia Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Juanita Ángel, Ph. D. Bogotá, Colombia Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Román Eduardo Castañeda, Dr. rer. nat. Bogotá, Colombia Universidad Nacional, Medellín, Colombia Manuel Franco, Ph. D. María Elena Gómez, Doctor Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Universidad del Valle, Cali Bogotá, Colombia Alberto Gómez, Ph. D. Gabriel Téllez, Ph. D. Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Universidad de los Andes, Bogotá, Colombia Bogotá, Colombia Jairo Roa-Rojas, Ph. D. John Mario González, Ph. D. Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Universidad de los Andes, Bogotá, Colombia Bogotá, Colombia Gloria Patricia Cardona Gómez, B.Sc., Ph. D. Ángela Stella Camacho Beltrán, Dr. rer. nat. Universidad de Antioquia, Medellin, Colombia Universidad de los Andes, Bogotá, Colombia Ciencias del Comportamiento Edgar González, Ph. D. Guillermo Páramo, M.Sc. Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Universidad Central, Bogotá, Colombia Bogotá, Colombia Rubén Ardila, Ph. -

Fossil Turtle from Colombia Round Like Car Tire 11 July 2012

Fossil turtle from Colombia round like car tire 11 July 2012 Paleontologists unearth the carapace of the giant turtle, Puentemys, which lived 60 million years ago in a hot tropical forest environment. Credit: Edwin Cadena The round shape of a new species of fossil turtle found in Cerrejon coal mine in Colombia may have warmed Cerrejon's fossil reptiles all seem to be extremely readily in the sun. Credit: Liz Bradford large. With its total length of 5 feet, Puentemys adds to growing evidence that following the extinction of the dinosaurs, tropical reptiles were Paleontologist Carlos Jaramillo's group at the much bigger than they are now. Fossils from Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Cerrejon offer an excellent opportunity to Panama and colleagues at North Carolina State understand the origins of tropical biodiversity in the University and the Florida Museum of Natural last 60 million years of Earth's history. History discovered a new species of fossil turtle that lived 60 million years ago in what is now The most peculiar feature of this new turtle is its northwestern South America. The team's findings extremely circular shell, about the size and shape were published in the Journal of Paleontology. of a big car tire. Edwin Cadena, post-doctoral fellow at North Carolina State University and lead author The new turtle species is named Puentemys of the paper, said that the turtle's round shape mushaisaensis because it was found in La Puente could have discouraged predators, including pit in Cerrejón Coal Mine, a place made famous for Titanoboa, and aided in regulating its body the discoveries, not only of the extinct Titanoboa, temperature. -

Biodiversidad-En-Cerrejon-Ilovepdf

en Pagina legal Cítese como: Escalante, Juan Fernando Alzate, Santiago Cañón, Obra completa: Báez, L. y F. Trujillo (Eds.). 2014. José Camilo Costa, Viviana Delgado, Alex Báez, Biodiversidad en Cerrejón. Carbones de Cerrejón, INVEMAR, Lilia Lastra, BIOMA Consultores, Fundación Omacha, Fondo para la Acción John Jairo Gómez, Luis Alonso Merizalde, División Ambiental y la Niñez. Bogotá, Colombia. 352 p. de Comunicaciones de Cerrejón, Carlos Jaramillo, Mary Luz Cañón, Mauricio Jaramillo P. y Laura Capítulos: Feged R. Blanco-Torres, A. y J. M. Rengifo. Herpetofauna de Cerrejón. Pp. 150-169. En: Báez, L. y F. Trujillo CERREJÓN (Eds.). 2014. Biodiversidad en Cerrejón. Carbones de Cerrejón, Fundación Omacha, Fondo para la Roberto Junguito Pombo Acción Ambiental y la Niñez. Bogotá, Colombia. Presidente de Cerrejón 352 p. Luis Germán Meneses Revisión científica Vicepresidente Ejecutivo de Operaciones José Vicente Rodríguez Mahecha Conservación Internacional Gabriel Bustos Gerente Gestión Ambiental Revisión Editorial Julio García Robles Lina Báez Especialista Biodiversidad Asistencia editorial Margarita Moreno Arocha FUNDACIÓN OMACHA Cartografía Fernando Sierra Dalila Caicedo Herrera Directora Ejecutiva Diseño y diagramación Luisa Fda. Cuervo Fernando Trujillo González zOOm diseño S.A.S. Director Científico Impresión FONDO PARA LA ACCIÓN AMBIENTAL Unión gráfica Ltda. Y LA NIÑEZ – FONDO ACCIÓN ISBN: 978-958-8554-36-5 José Luis Gómez Director Ejecutivo Fotografías Fernando Trujillo, Lina Báez, Juan Manuel Alejandro Silva Espinosa Rengifo, Julio García -

Study Names New Ancient Crocodile Relative from the Land of Titanoboa 15 September 2011, by Danielle Torrent

Study names new ancient crocodile relative from the land of Titanoboa 15 September 2011, by Danielle Torrent Did an ancient crocodile relative give the world's the department of geoscience at the University of largest snake a run for its money? Iowa, who was not involved in the study. In a new study appearing Sept. 15 in the journal "We're facing some serious ecological changes Palaeontology, University of Florida researchers now," Brochu said. "A lot of them have to do with describe a new 20-foot extinct species discovered climate and if we want to understand how living in the same Colombian coal mine with Titanoboa, things are going to respond to changes in climate, the world's largest snake. The findings help we need to understand how they responded in the scientists better understand the diversity of animals past. This really is a wonderful group for that that occupied the oldest known rainforest because they managed to survive some ecosystem, which had higher temperatures than catastrophes, but they seemed not to survive today, and could be useful for understanding the others and their diversity does seem to change impacts of a warmer climate in the future. along with these ecological signals." The 60-million-year-old freshwater relative to The species is the second ancient crocodyliform modern crocodiles is the first known land animal found in the Cerrejon mine of northern Colombia, from the Paleocene New World tropics specialized one of the world's largest open-pit coal mines. The for eating fish, meaning it competed with Titanoboa excavations were led by study co-authors Jonathan for food.