Osteological Evidence for Shorebird Affinities of the Flamingos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PALEOGENE FOSSILS and the RADIATION of MODERN BIRDS H�Q�� F

The Auk 122(4):1049–1054, 2005 © The American Ornithologists’ Union, 2005. Printed in USA. OVERVIEW PALEOGENE FOSSILS AND THE RADIATION OF MODERN BIRDS Hq F. Jrx1 Division of Birds, MRC-116, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. 20013, USA M birds arose mainly in 1989, Mayr and Manegold 2004), and others. the Neogene Period (1.8–23.8 mya), and mod- Paleogene fossils also document diverse extinct ern species mainly in the Plio-Pleistocene branches of the neornithine tree, ranging from (0.08–5.3 mya). Neogene fossil birds generally large pseudotoothed seabirds to giant fl ightless resemble modern taxa, and those that cannot land birds to small zygodactyl perching birds be a ributed to a modern genus or species (Ballmann 1969, Harrison and Walker 1976, can usually be placed in a modern family with Andors 1992). a fair degree of confi dence (e.g. Becker 1987, Before the Paleogene, fossils of putative neor- Olson and Rasmussen 2001). Fossil birds from nithine birds are sparse and fragmentary (Hope earlier in the Cenozoic can be more challeng- 2002), and their phylogenetic placement is all ing to classify. The fossil birds of the Paleogene the more equivocal. The Paleogene is thus a cru- (23.8–65.5 mya) are clearly a ributable to the cial time period for understanding the history of Neornithes (modern birds), and the earliest diversifi cation of birds, particularly with respect well-established records of most traditional to the deeper branches of the neornithine tree. orders and families of modern birds occur then. -

A Systematic Ornithological Study of the Northern Region of Iranian Plateau, Including Bird Names in Native Language

Available online a t www.pelagiaresearchlibrary.com Pelagia Research Library European Journal of Experimental Biology, 2012, 2 (1):222-241 ISSN: 2248 –9215 CODEN (USA): EJEBAU A systematic ornithological study of the Northern region of Iranian Plateau, including bird names in native language Peyman Mikaili 1, (Romana) Iran Dolati 2,*, Mohammad Hossein Asghari 3, Jalal Shayegh 4 1Department of Pharmacology, School of Medicine, Urmia University of Medical Sciences, Urmia, Iran 2Islamic Azad University, Mahabad branch, Mahabad, Iran 3Islamic Azad University, Urmia branch, Urmia, Iran 4Department of Veterinary Medicine, Faculty of Agriculture and Veterinary, Shabestar branch, Islamic Azad University, Shabestar, Iran ________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT A major potation of this study is devoted to presenting almost all main ornithological genera and species described in Gilanprovince, located in Northern Iran. The bird names have been listed and classified according to the scientific codes. An etymological study has been presented for scientific names, including genus and species. If it was possible we have provided the etymology of Persian and Gilaki native names of the birds. According to our best knowledge, there was no previous report gathering and describing the ornithological fauna of this part of the world. Gilan province, due to its meteorological circumstances and the richness of its animal life has harbored a wide range of animals. Therefore, the nomenclature system used by the natives for naming the animals, specially birds, has a prominent stance in this country. Many of these local and dialectal names of the birds have been entered into standard language of the country (Persian language). The study has presented majority of comprehensive list of the Gilaki bird names, categorized according to the ornithological classifications. -

Download Vol. 11, No. 3

BULLETIN OF THE FLORIDA STATE MUSEUM BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES Volume 11 Number 3 CATALOGUE OF FOSSIL BIRDS: Part 3 (Ralliformes, Ichthyornithiformes, Charadriiformes) Pierce Brodkorb M,4 * . /853 0 UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA Gainesville 1967 Numbers of the BULLETIN OF THE FLORIDA STATE MUSEUM are pub- lished at irregular intervals. Volumes contain about 800 pages and are not nec- essarily completed in any one calendar year. WALTER AuFFENBERC, Managing Editor OLIVER L. AUSTIN, JA, Editor Consultants for this issue. ~ HILDEGARDE HOWARD ALExANDER WErMORE Communications concerning purchase or exchange of the publication and all manuscripts should be addressed to the Managing Editor of the Bulletin, Florida State Museum, Seagle Building, Gainesville, Florida. 82601 Published June 12, 1967 Price for this issue $2.20 CATALOGUE OF FOSSIL BIRDS: Part 3 ( Ralliformes, Ichthyornithiformes, Charadriiformes) PIERCE BRODKORBl SYNOPSIS: The third installment of the Catalogue of Fossil Birds treats 84 families comprising the orders Ralliformes, Ichthyornithiformes, and Charadriiformes. The species included in this section number 866, of which 215 are paleospecies and 151 are neospecies. With the addenda of 14 paleospecies, the three parts now published treat 1,236 spDcies, of which 771 are paleospecies and 465 are living or recently extinct. The nominal order- Diatrymiformes is reduced in rank to a suborder of the Ralliformes, and several generally recognized families are reduced to subfamily status. These include Geranoididae and Eogruidae (to Gruidae); Bfontornithidae -

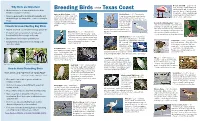

Breeding Birds of the Texas Coast

Roseate Spoonbill • L 32”• Uncom- Why Birds are Important of the mon, declining • Unmistakable pale Breeding Birds Texas Coast pink wading bird with a long bill end- • Bird abundance is an important indicator of the ing in flat “spoon”• Nests on islands health of coastal ecosystems in vegetation • Wades slowly through American White Pelican • L 62” Reddish Egret • L 30”• Threatened in water, sweeping touch-sensitive bill •Common, increasing • Large, white • Revenue generated by hunting, photography, and Texas, decreasing • Dark morph has slate- side to side in search of prey birdwatching helps support the coastal economy in bird with black flight feathers and gray body with reddish breast, neck, and Chuck Tague bright yellow bill and pouch • Nests Texas head; white morph completely white – both in groups on islands with sparse have pink bill with Black-bellied Whistling-Duck vegetation • Preys on small fish in black tip; shaggy- • L 21”• Lo- groups looking plumage cally common, increasing • Goose-like duck Threats to Island-Nesting Bay Birds Chuck Tague with long neck and pink legs, pinkish-red bill, Greg Lavaty • Nests in mixed- species colonies in low vegetation or on black belly, and white eye-ring • Nests in tree • Habitat loss from erosion and wetland degradation cavities • Occasionally nests in mesquite and Brown Pelican • L 51”• Endangered in ground • Uses quick, erratic movements to • Predators such as raccoons, feral hogs, and stir up prey Chuck Tague other woody vegetation on bay islands Texas, but common and increasing • Large -

Onetouch 4.0 Scanned Documents

/ Chapter 2 THE FOSSIL RECORD OF BIRDS Storrs L. Olson Department of Vertebrate Zoology National Museum of Natural History Smithsonian Institution Washington, DC. I. Introduction 80 II. Archaeopteryx 85 III. Early Cretaceous Birds 87 IV. Hesperornithiformes 89 V. Ichthyornithiformes 91 VI. Other Mesozojc Birds 92 VII. Paleognathous Birds 96 A. The Problem of the Origins of Paleognathous Birds 96 B. The Fossil Record of Paleognathous Birds 104 VIII. The "Basal" Land Bird Assemblage 107 A. Opisthocomidae 109 B. Musophagidae 109 C. Cuculidae HO D. Falconidae HI E. Sagittariidae 112 F. Accipitridae 112 G. Pandionidae 114 H. Galliformes 114 1. Family Incertae Sedis Turnicidae 119 J. Columbiformes 119 K. Psittaciforines 120 L. Family Incertae Sedis Zygodactylidae 121 IX. The "Higher" Land Bird Assemblage 122 A. Coliiformes 124 B. Coraciiformes (Including Trogonidae and Galbulae) 124 C. Strigiformes 129 D. Caprimulgiformes 132 E. Apodiformes 134 F. Family Incertae Sedis Trochilidae 135 G. Order Incertae Sedis Bucerotiformes (Including Upupae) 136 H. Piciformes 138 I. Passeriformes 139 X. The Water Bird Assemblage 141 A. Gruiformes 142 B. Family Incertae Sedis Ardeidae 165 79 Avian Biology, Vol. Vlll ISBN 0-12-249408-3 80 STORES L. OLSON C. Family Incertae Sedis Podicipedidae 168 D. Charadriiformes 169 E. Anseriformes 186 F. Ciconiiformes 188 G. Pelecaniformes 192 H. Procellariiformes 208 I. Gaviiformes 212 J. Sphenisciformes 217 XI. Conclusion 217 References 218 I. Introduction Avian paleontology has long been a poor stepsister to its mammalian counterpart, a fact that may be attributed in some measure to an insufRcien- cy of qualified workers and to the absence in birds of heterodont teeth, on which the greater proportion of the fossil record of mammals is founded. -

Flamingos, Stilts and Whales

Nature Vol. 289 29 January 1981 347 Flamingos, stilts and whales from Andrew Milner THE phylogenetic position of the flamingos (family Phoenicopteridae) has long been the subject of controversy among avian systematists with some workers supporting relationship with the Anseriformes (ducks and geese) whilst others favour association with the Ciconiiformes (storks, herons and ibis). The evidence has been reviewed recently by Olson and Feduccia (Relationships and Evolulion oj Flamingos (A ves: Phoenicopteridae) Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology 316, Smithsonian Institution Press; 1980) who have developed an earlier proposal by Feduccia that the flamingos fall within the Charadriiformes (waders, gulls and auks). Characteristics of the musculature, the skeleton, the natal down and the endoparasitic cestodes all lead to the conclusion that the closest living relatives of the flamingos are the Recurvirostridae (stilts and avocets) and, more specifically, the Australian Banded Stilt (Cladorhynchus). This remarkable bird lives in colonies frequenting temporary salt lakes in southern Australia and its behaviour, pattern of breeding and life history all bear specific similarities to those of flamingos. The B earliest certain fossil flamingo from the Eocene of Wyoming is described by Head of a Lesser Flamingo, Phoeniconaias minor (A), compared with that of a Black Right Olson and Feduccia and supports their Whale, Eubalaena glacialis (B), to show the hypothesis by being morphologically convergent similarities in the filter·feeding intermediate -

Appendix A. Supplementary Material

Appendix A. Supplementary material Comprehensive taxon sampling and vetted fossils help clarify the time tree of shorebirds (Aves, Charadriiformes) David Cernˇ y´ 1,* & Rossy Natale2 1Department of the Geophysical Sciences, University of Chicago, Chicago 60637, USA 2Department of Organismal Biology & Anatomy, University of Chicago, Chicago 60637, USA *Corresponding Author. Email: [email protected] Contents 1 Fossil Calibrations 2 1.1 Calibrations used . .2 1.2 Rejected calibrations . 22 2 Outgroup sequences 30 2.1 Neornithine outgroups . 33 2.2 Non-neornithine outgroups . 39 3 Supplementary Methods 72 4 Supplementary Figures and Tables 74 5 Image Credits 91 References 99 1 1 Fossil Calibrations 1.1 Calibrations used Calibration 1 Node calibrated. MRCA of Uria aalge and Uria lomvia. Fossil taxon. Uria lomvia (Linnaeus, 1758). Specimen. CASG 71892 (referred specimen; Olson, 2013), California Academy of Sciences, San Francisco, CA, USA. Lower bound. 2.58 Ma. Phylogenetic justification. As in Smith (2015). Age justification. The status of CASG 71892 as the oldest known record of either of the two spp. of Uria was recently confirmed by the review of Watanabe et al. (2016). The younger of the two marine transgressions at the Tolstoi Point corresponds to the Bigbendian transgression (Olson, 2013), which contains the Gauss-Matuyama magnetostratigraphic boundary (Kaufman and Brigham-Grette, 1993). Attempts to date this reversal have been recently reviewed by Ohno et al. (2012); Singer (2014), and Head (2019). In particular, Deino et al. (2006) were able to tightly bracket the age of the reversal using high-precision 40Ar/39Ar dating of two tuffs in normally and reversely magnetized lacustrine sediments from Kenya, obtaining a value of 2.589 ± 0.003 Ma. -

Attachment J Assessment of Existing Paleontologic Data Along with Field Survey Results for the Jonah Field

Attachment J Assessment of Existing Paleontologic Data Along with Field Survey Results for the Jonah Field June 12, 2007 ABSTRACT This is compilation of a technical analysis of existing paleontological data and a limited, selective paleontological field survey of the geologic bedrock formations that will be impacted on Federal lands by construction associated with energy development in the Jonah Field, Sublette County, Wyoming. The field survey was done on approximately 20% of the field, primarily where good bedrock was exposed or where there were existing, debris piles from recent construction. Some potentially rich areas were inaccessible due to biological restrictions. Heavily vegetated areas were not examined. All locality data are compiled in the separate confidential appendix D. Uinta Paleontological Associates Inc. was contracted to do this work through EnCana Oil & Gas Inc. In addition BP and Ultra Resources are partners in this project as they also have holdings in the Jonah Field. For this project, we reviewed a variety of geologic maps for the area (approximately 47 sections); none of maps have a scale better than 1:100,000. The Wyoming 1:500,000 geology map (Love and Christiansen, 1985) reveals two Eocene geologic formations with four members mapped within or near the Jonah Field (Wasatch – Alkali Creek and Main Body; Green River – Laney and Wilkins Peak members). In addition, Winterfeld’s 1997 paleontology report for the proposed Jonah Field II Project was reviewed carefully. After considerable review of the literature and museum data, it became obvious that the portion of the mapped Alkali Creek Member in the Jonah Field is probably misinterpreted. -

A Skull of a Very Large Crane from the Late Miocene of Southern Germany, with Notes on the Phylogenetic Interrelationships of Extant Gruinae

Journal of Ornithology https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-020-01799-0 ORIGINAL ARTICLE A skull of a very large crane from the late Miocene of Southern Germany, with notes on the phylogenetic interrelationships of extant Gruinae Gerald Mayr1 · Thomas Lechner2 · Madelaine Böhme2 Received: 3 June 2020 / Revised: 1 July 2020 / Accepted: 2 July 2020 © The Author(s) 2020 Abstract We describe a partial skull of a very large crane from the early late Miocene (Tortonian) hominid locality Hammerschmiede in southern Germany, which is the oldest fossil record of the Gruinae (true cranes). The fossil exhibits an unusual preservation in that only the dorsal portions of the neurocranium and beak are preserved. Even though it is, therefore, very fragmentary, two morphological characteristics are striking and of paleobiological signifcance: its large size and the very long beak. The fossil is from a species the size of the largest extant cranes and represents the earliest record of a large-sized crane in Europe. Overall, the specimen resembles the skull of the extant, very long-beaked Siberian Crane, Leucogeranus leucogeranus, but its afnities within Gruinae cannot be determined owing to the incomplete preservation. Judging from its size, the fossil may possibly belong to the very large “Grus” pentelici, which stems from temporally and geographically proximate sites. The long beak of the Hammerschmiede crane conforms to an open freshwater paleohabitat, which prevailed at the locality. Keywords Aves · Evolution · Gruidae · Systematics · Tortonian Zusammenfassung Ein Schädel eines sehr großen Kranichs aus dem Obermiozän Süddeutschlands, mit Bemerkungen zu den Verwandtschaftsbeziehungen heutiger Gruinae Wir beschreiben einen partiell erhaltenen Schädel eines sehr großen Kranichs aus dem frühen Obermiozän (Tortonium) der Hominiden-Fundstelle Hammerschmiede in Süddeutschland, welcher den ältesten Fossilnachweis der Gruinae (echte Kraniche) repräsentiert. -

AOU Classification Committee – North and Middle America

AOU Classification Committee – North and Middle America Proposal Set 2016-C No. Page Title 01 02 Change the English name of Alauda arvensis to Eurasian Skylark 02 06 Recognize Lilian’s Meadowlark Sturnella lilianae as a separate species from S. magna 03 20 Change the English name of Euplectes franciscanus to Northern Red Bishop 04 25 Transfer Sandhill Crane Grus canadensis to Antigone 05 29 Add Rufous-necked Wood-Rail Aramides axillaris to the U.S. list 06 31 Revise our higher-level linear sequence as follows: (a) Move Strigiformes to precede Trogoniformes; (b) Move Accipitriformes to precede Strigiformes; (c) Move Gaviiformes to precede Procellariiformes; (d) Move Eurypygiformes and Phaethontiformes to precede Gaviiformes; (e) Reverse the linear sequence of Podicipediformes and Phoenicopteriformes; (f) Move Pterocliformes and Columbiformes to follow Podicipediformes; (g) Move Cuculiformes, Caprimulgiformes, and Apodiformes to follow Columbiformes; and (h) Move Charadriiformes and Gruiformes to precede Eurypygiformes 07 45 Transfer Neocrex to Mustelirallus 08 48 (a) Split Ardenna from Puffinus, and (b) Revise the linear sequence of species of Ardenna 09 51 Separate Cathartiformes from Accipitriformes 10 58 Recognize Colibri cyanotus as a separate species from C. thalassinus 11 61 Change the English name “Brush-Finch” to “Brushfinch” 12 62 Change the English name of Ramphastos ambiguus 13 63 Split Plain Wren Cantorchilus modestus into three species 14 71 Recognize the genus Cercomacroides (Thamnophilidae) 15 74 Split Oceanodroma cheimomnestes and O. socorroensis from Leach’s Storm- Petrel O. leucorhoa 2016-C-1 N&MA Classification Committee p. 453 Change the English name of Alauda arvensis to Eurasian Skylark There are a dizzying number of larks (Alaudidae) worldwide and a first-time visitor to Africa or Mongolia might confront 10 or more species across several genera. -

Ichnotaxonomy of the Eocene Green River Formation

Ichnotaxonomy of the Eocene Green River Formation, Soldier Summit and Spanish Fork Canyon, Uinta Basin, Utah: Interpreting behaviors, lifestyles, and erecting the Cochlichnus Ichnofacies By © 2018 Joshua D. Hogue B.S. Old Dominion University, 2013 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Geology and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science. Chair: Dr. Stephen T. Hasiotis Dr. Paul Selden Dr. Georgios Tsoflias Date Defended: May 1, 2018 ii The thesis committee for Joshua D. Hogue certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Ichnotaxonomy of the Eocene Green River Formation, Soldier Summit and Spanish Fork Canyon, Uinta Basin, Utah: Interpreting behaviors, lifestyles, and erecting the Cochlichnus Ichnofacies Chair: Dr. Stephen T. Hasiotis Date Approved: May 1, 2018 iii ABSTRACT The Eocene Green River Formation in the Uinta Basin, Utah, has a diverse ichnofauna. Nineteen ichnogenera and 26 ichnospecies were identified: Acanthichnus cursorius, Alaripeda lofgreni, c.f. Aquatilavipes isp., Aulichnites (A. parkerensis and A. tsouloufeidos isp. nov.), Aviadactyla (c.f. Av. isp. and Av. vialovi), Avipeda phoenix, Cochlichnus (C. anguineus and C. plegmaeidos isp. nov.), Conichnus conichnus, Fuscinapeda texana, Glaciichnium liebegastensis, Glaroseidosichnus ign. nov. gierlowskii isp. nov., Gruipeda (G. fuenzalidae and G. gryponyx), Midorikawapeda ign. nov. semipalmatus isp. nov., Planolites montanus, Presbyorniformipes feduccii, Protovirgularia dichotoma, Sagittichnus linki, Treptichnus (T. bifurcus, T. pedum, and T. vagans), and Tsalavoutichnus ign. nov. (Ts. ericksonii isp. nov. and Ts. leptomonopati isp. nov.). Four ichnocoenoses are represented by the ichnofossils—Cochlichnus, Conichnus, Presbyorniformipes, and Treptichnus—representing dwelling, feeding, grazing, locomotion, predation, pupation, and resting behaviors of organisms in environments at and around the sediment-water-air interface. -

A Partial Classification of Waterfowl (Anatidae) Based on Single-Copy Dna

A PARTIAL CLASSIFICATION OF WATERFOWL (ANATIDAE) BASED ON SINGLE-COPY DNA CORT S. MADSEN, KEVIN P. MCHUGH, AND SIWO R. DE KLOET Instituteof MolecularBiophysics, The Florida State University, Tallahassee, Florida 32306 USA ABSTR^CT.--Single-copyDNA-DNA hybridizationwas used to establishphylogenetic re- lationshipsamong 13 speciesof waterfowl (Anatidae) chosenfrom 10 tribes. On the basisof UPGMA clusteringof ATtodistances, we suggestthat the tribes Anatini, Aythyini, Tadornini, Mergini, and Cairinini diverged more recently than the Anserini, Stictonettini,Oxyurini, Dendrocygnini,and Anseranatini.The FreckledDuck (Stictonettanaevosa, tribe Stictonettini) is only distantlyrelated to the other Anatidae.Presumably the lineage divergedvery early. The sheldgeese(tribe Tadornini) and the true geese(Anserini) are only remotely related. The Oxyurini, consideredto be in the subfamilyAnatinae, is remotely related to the other Anatidae. The Dendrocygnini form an isolatedtribe with no closerelationship to the swans and geese(subfamily Anserinae). We found that the screamers(Anhimidae) are distantly related to the Anatidae. A method to estimate missing cells in a data matrix of pairwise distancesis presented. ReceivedI May 1987,accepted 16 February1988. RECENTLY,nucleic acid sequenceanalysis has up about 10-40% of the total DNA (Eden et al. been usedto estimaterelationships of many or- 1978) but containsonly a small percentageof ganisms. The analysis can include direct se- the total sequencediversity. The remaining60- quencing of individual cloned genes