Full Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

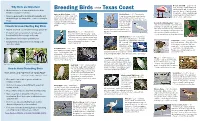

Breeding Birds of the Texas Coast

Roseate Spoonbill • L 32”• Uncom- Why Birds are Important of the mon, declining • Unmistakable pale Breeding Birds Texas Coast pink wading bird with a long bill end- • Bird abundance is an important indicator of the ing in flat “spoon”• Nests on islands health of coastal ecosystems in vegetation • Wades slowly through American White Pelican • L 62” Reddish Egret • L 30”• Threatened in water, sweeping touch-sensitive bill •Common, increasing • Large, white • Revenue generated by hunting, photography, and Texas, decreasing • Dark morph has slate- side to side in search of prey birdwatching helps support the coastal economy in bird with black flight feathers and gray body with reddish breast, neck, and Chuck Tague bright yellow bill and pouch • Nests Texas head; white morph completely white – both in groups on islands with sparse have pink bill with Black-bellied Whistling-Duck vegetation • Preys on small fish in black tip; shaggy- • L 21”• Lo- groups looking plumage cally common, increasing • Goose-like duck Threats to Island-Nesting Bay Birds Chuck Tague with long neck and pink legs, pinkish-red bill, Greg Lavaty • Nests in mixed- species colonies in low vegetation or on black belly, and white eye-ring • Nests in tree • Habitat loss from erosion and wetland degradation cavities • Occasionally nests in mesquite and Brown Pelican • L 51”• Endangered in ground • Uses quick, erratic movements to • Predators such as raccoons, feral hogs, and stir up prey Chuck Tague other woody vegetation on bay islands Texas, but common and increasing • Large -

Onetouch 4.0 Scanned Documents

/ Chapter 2 THE FOSSIL RECORD OF BIRDS Storrs L. Olson Department of Vertebrate Zoology National Museum of Natural History Smithsonian Institution Washington, DC. I. Introduction 80 II. Archaeopteryx 85 III. Early Cretaceous Birds 87 IV. Hesperornithiformes 89 V. Ichthyornithiformes 91 VI. Other Mesozojc Birds 92 VII. Paleognathous Birds 96 A. The Problem of the Origins of Paleognathous Birds 96 B. The Fossil Record of Paleognathous Birds 104 VIII. The "Basal" Land Bird Assemblage 107 A. Opisthocomidae 109 B. Musophagidae 109 C. Cuculidae HO D. Falconidae HI E. Sagittariidae 112 F. Accipitridae 112 G. Pandionidae 114 H. Galliformes 114 1. Family Incertae Sedis Turnicidae 119 J. Columbiformes 119 K. Psittaciforines 120 L. Family Incertae Sedis Zygodactylidae 121 IX. The "Higher" Land Bird Assemblage 122 A. Coliiformes 124 B. Coraciiformes (Including Trogonidae and Galbulae) 124 C. Strigiformes 129 D. Caprimulgiformes 132 E. Apodiformes 134 F. Family Incertae Sedis Trochilidae 135 G. Order Incertae Sedis Bucerotiformes (Including Upupae) 136 H. Piciformes 138 I. Passeriformes 139 X. The Water Bird Assemblage 141 A. Gruiformes 142 B. Family Incertae Sedis Ardeidae 165 79 Avian Biology, Vol. Vlll ISBN 0-12-249408-3 80 STORES L. OLSON C. Family Incertae Sedis Podicipedidae 168 D. Charadriiformes 169 E. Anseriformes 186 F. Ciconiiformes 188 G. Pelecaniformes 192 H. Procellariiformes 208 I. Gaviiformes 212 J. Sphenisciformes 217 XI. Conclusion 217 References 218 I. Introduction Avian paleontology has long been a poor stepsister to its mammalian counterpart, a fact that may be attributed in some measure to an insufRcien- cy of qualified workers and to the absence in birds of heterodont teeth, on which the greater proportion of the fossil record of mammals is founded. -

Flamingos, Stilts and Whales

Nature Vol. 289 29 January 1981 347 Flamingos, stilts and whales from Andrew Milner THE phylogenetic position of the flamingos (family Phoenicopteridae) has long been the subject of controversy among avian systematists with some workers supporting relationship with the Anseriformes (ducks and geese) whilst others favour association with the Ciconiiformes (storks, herons and ibis). The evidence has been reviewed recently by Olson and Feduccia (Relationships and Evolulion oj Flamingos (A ves: Phoenicopteridae) Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology 316, Smithsonian Institution Press; 1980) who have developed an earlier proposal by Feduccia that the flamingos fall within the Charadriiformes (waders, gulls and auks). Characteristics of the musculature, the skeleton, the natal down and the endoparasitic cestodes all lead to the conclusion that the closest living relatives of the flamingos are the Recurvirostridae (stilts and avocets) and, more specifically, the Australian Banded Stilt (Cladorhynchus). This remarkable bird lives in colonies frequenting temporary salt lakes in southern Australia and its behaviour, pattern of breeding and life history all bear specific similarities to those of flamingos. The B earliest certain fossil flamingo from the Eocene of Wyoming is described by Head of a Lesser Flamingo, Phoeniconaias minor (A), compared with that of a Black Right Olson and Feduccia and supports their Whale, Eubalaena glacialis (B), to show the hypothesis by being morphologically convergent similarities in the filter·feeding intermediate -

Appendix A. Supplementary Material

Appendix A. Supplementary material Comprehensive taxon sampling and vetted fossils help clarify the time tree of shorebirds (Aves, Charadriiformes) David Cernˇ y´ 1,* & Rossy Natale2 1Department of the Geophysical Sciences, University of Chicago, Chicago 60637, USA 2Department of Organismal Biology & Anatomy, University of Chicago, Chicago 60637, USA *Corresponding Author. Email: [email protected] Contents 1 Fossil Calibrations 2 1.1 Calibrations used . .2 1.2 Rejected calibrations . 22 2 Outgroup sequences 30 2.1 Neornithine outgroups . 33 2.2 Non-neornithine outgroups . 39 3 Supplementary Methods 72 4 Supplementary Figures and Tables 74 5 Image Credits 91 References 99 1 1 Fossil Calibrations 1.1 Calibrations used Calibration 1 Node calibrated. MRCA of Uria aalge and Uria lomvia. Fossil taxon. Uria lomvia (Linnaeus, 1758). Specimen. CASG 71892 (referred specimen; Olson, 2013), California Academy of Sciences, San Francisco, CA, USA. Lower bound. 2.58 Ma. Phylogenetic justification. As in Smith (2015). Age justification. The status of CASG 71892 as the oldest known record of either of the two spp. of Uria was recently confirmed by the review of Watanabe et al. (2016). The younger of the two marine transgressions at the Tolstoi Point corresponds to the Bigbendian transgression (Olson, 2013), which contains the Gauss-Matuyama magnetostratigraphic boundary (Kaufman and Brigham-Grette, 1993). Attempts to date this reversal have been recently reviewed by Ohno et al. (2012); Singer (2014), and Head (2019). In particular, Deino et al. (2006) were able to tightly bracket the age of the reversal using high-precision 40Ar/39Ar dating of two tuffs in normally and reversely magnetized lacustrine sediments from Kenya, obtaining a value of 2.589 ± 0.003 Ma. -

Diversity, Abundance and Activity Pattern of Wetland Birds Along Cauvery Basin at Kumbakonam, Tamil Nadu, India by Veeramani

Global Journal of Science Frontier Research: C Biological Science Volume 18 Issue 4 Version 1.0 Year 2018 Type: Double Blind Peer Reviewed International Research Journal Publisher: Global Journals Online ISSN: 2249-4626 & Print ISSN: 0975-5896 Diversity, Abundance and Activity Pattern of Wetland Birds Along Cauvery Basin at Kumbakonam, Tamil Nadu, India By Veeramani. A & Usha. S Governmental Arts College (Autonomous), Kumbakonam Abstract- The role of avifauna in the ecosystem are as scavenger, pollinators, seeds dispersal agents and predators of insect pest and also an important indicator to evaluate different habitats both qualitatively and quantitatively. Wetlands are also important for birds for their feeding, roosting, nesting and rearing young activities. The present study was conducted in the cultivated areas and water bodies of the villages adjacent to Kumbakonam. Birds were estimated using total count method. Activity pattern and physio-chemical parameters of fresh water habitats were identified using standard methodologies. Thirty one species of water birds belonging to 14 families have been identified in the waterways at the study area. The density of diving birds, swimming birds, small waders, large waders and aerial foragers were slightly higher in the month of November than March. Most of the birds observed and recorded higher in monsoon followed by pre-monsoon and post-monsoon seasons. Physio-chemical parameters of water in the study sites was slightly alkaline nature and contained high amounts of pH, dissolved oxygen, electrical conductivity, salinity and turbidity throughout the study period. Keywords: wetland birds, diversity, density, richness, activity pattern, physio-chemical parameters. GJSFR-C Classification: FOR Code: 060899 DiversityAbundanceandActivityPatternofWetlandBirdsAlongCauveryBasinatKumbakonamTamilNaduIndia Strictly as per the compliance and regulations of: © 2018. -

Sea and Coastal Birds of Lebanon

tock tters hu -S ro lo The Globally Threats facing the sea and coastal birds: High F . S rates of bycatch mortality in adults, pollution, . Threatened A predation (mainly by large gulls, rats and © Species cats), disturbance, lowered water level around The Audouin’s Gull nests, lead poisoning, egg collection and is considered natio- collisions; loss of foraging habitat and breeding Sea and coastal birds nally threatened as it sites; shooting and persecution by fishers, formerly bred in Palm illegal hunting, wetland alteration, and over- of Lebanon Islands until the seventies exploitation of fish stocks, oil spill and climate of the last century. It ceased from nesting due change. to disturbance. This species breeds on unin- habited islands and islets and may abandon By convention all of the Sphenisciformes and the nest under the pressure of heavy visita- Procellariiformes, all of the Pelecaniformes Legal status of sea tion. Lives mainly on small fish. Presently, this and Suliformes except the darters, and few species is a nonbreeding Charadriiformes (the skuas, gulls, terns, auks, and coastal birds. migrant in Lebanon. and phalaropes) are classified as seabirds. All the sea and coastal birds are protected by im h c the Lebanese Hunting Law 580/2004. Many of a Many waders (or shorebirds), including herons, o J them are also covered by the AEWA Agreement, a are also highly marine, living on the sea’s edge c i CMS, and Barcelona Convention. s (coast), but are treated as coastal birds. s e J © The content of this leaflet was developed by Dr. Ghassan Ramadan-Jardai as part of the project The Yelkouan Shear- “Market policy and legislative development for water is endemic to mainstreaming sustainable management of marine the Mediterranean & globally vulnerable. -

An Update of Wallacels Zoogeographic Regions of the World

REPORTS To examine the temporal profile of ChC produc- specification of a distinct, and probably the last, 3. G. A. Ascoli et al., Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9, 557 (2008). tion and their correlation to laminar deployment, cohort in this lineage—the ChCs. 4. J. Szentágothai, M. A. Arbib, Neurosci. Res. Program Bull. 12, 305 (1974). we injected a single pulse of BrdU into pregnant A recent study demonstrated that progeni- CreER 5. P. Somogyi, Brain Res. 136, 345 (1977). Nkx2.1 ;Ai9 females at successive days be- tors below the ventral wall of the lateral ventricle 6. L. Sussel, O. Marin, S. Kimura, J. L. Rubenstein, tween E15 and P1 to label mitotic progenitors, (i.e., VGZ) of human infants give rise to a medial Development 126, 3359 (1999). each paired with a pulse of tamoxifen at E17 to migratory stream destined to the ventral mPFC 7. S. J. Butt et al., Neuron 59, 722 (2008). + 18 8. H. Taniguchi et al., Neuron 71, 995 (2011). label NKX2.1 cells (Fig. 3A). We first quanti- ( ). Despite species differences in the develop- 9. L. Madisen et al., Nat. Neurosci. 13, 133 (2010). fied the fraction of L2 ChCs (identified by mor- mental timing of corticogenesis, this study and 10. J. Szabadics et al., Science 311, 233 (2006). + phology) in mPFC that were also BrdU+. Although our findings raise the possibility that the NKX2.1 11. A. Woodruff, Q. Xu, S. A. Anderson, R. Yuste, Front. there was ChC production by E15, consistent progenitors in VGZ and their extended neurogenesis Neural Circuits 3, 15 (2009). -

AMERICAN ORNITHOLOGISTS' UNION FINANCIAL STATEMENTS for the Year Ended July 31, 1986

18AA AMERICAN ORNITHOLOGISTS' UNION FINANCIAL STATEMENTS For the Year Ended July 31, 1986 To the Membership American Ornithologists'Union We have examinedthe balancesheet of the American Ornithologists'Union as of July 31, 1986, and the related statementsof supportand revenue,expenses, capital additions,and changesin fund balancesand of changesin financialposition for the year then ended.Our examinationwas made in accordancewith generallyaccepted auditing standards and, accordingly,included such testsof the accountingrecords and suchother auditing proceduresas we considerednecessary in the circumstances. In our opinion,the financialstatements referred to abovepresent fairly the financialposition of the AmericanOrnithologists' Union at July 31, 1986, and the resultsof its operations,and the changesin fund balancesand its financial positionfor the year then ended, in conformity with generallyaccepted accounting principles applied on a consistentbasis. October 3, 1986 Schehrer, Harrod & Bennett Professional Association Certified Public Accountants Lawrence, Kansas AMERICAN ORNITHOLOGISTS' UNION BALANCE SHEET As of July 31, 1986 Operating Endowment Total Funds Funds All Funds Assets Cash ............................................................................................................................$ 112,049 $ 112,049 Refunds receivable .....................................................................................1,796 1,796 Inventories (Note 1)* ...............................................................................201,078 -

Biology of the Eared Grebe and Wilson's Phalarope in the Nonbreeding Season: a Study of Adaptations to Saline Lakes

BIOLOGY OF THE EAREDGREBEAND WILSONS’ PHALAROPE IN THE NONBREEDING SEASON: A STUDY OF ADAPTATIONS TO SALINE LAKES Joseph R. Jehl, Jr. Sea World Research Institute Hubbs Marine Research Center 1700 South Shores Road San Diego, California U.S.A. 92 109 Studies in Avian Biology No. 12 A PUBLICATION OF THE COOPER ORNITHOLOGICAL SOCIEIY’ Cover Photograph: Eared Grebes (Podiceps nigricollis] at Mono Lake, California, October. 1985. Photograph by J. R. Jehl, Jr. i Edited by FRANK A. PITELKA at the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology University of California Berkeley, CA 94720 EDITORIAL ADVISORS FOR SAB 12 Ralph W. Schreiber Jared Verner David W. Winkler Studiesin Avian Biology is a series of works too long for The Condor, published at irregular intervals by the Cooper Ornithological Society. Manuscripts for con- sideration should be submitted to the current editor, Joseph R. Jehl, Jr., Sea World Research Institute, 1700 South Shores Road, San Diego, CA 92 109. Style and format should follow those of previous issues. Price: $14.00 including postage and handling. All orders cash in advance; make checks payable to Cooper Ornithological Society. Send orders to James R. North- ern, Assistant Treasurer, Cooper Ornithological Society, Department of Biology, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90024. ISBN: O-935868-39-9 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 88-062658 Printed at Allen Press, Inc., Lawrence, Kansas 66044 Issued 7 October 1988 Copyright by Cooper Ornithological Society, 1988 ii CONTENTS Abstract ............................. 1 Introduction ......................... 5 Eared Grebe ......................... 5 Methods ........................... 6 The Annual Cycle at Mono Lake ..... 8 Chronology ...................... 8 Composition of the population ..... 9 Size of the Mono Lake flock ...... -

Wader Studies in the Soviet Union P.S

Tomkowch . Wader studies m the Soviet Union Wader studies in the Soviet Union P.S. Tomkovich Tomkovich, P.S. 1998. Wader studies in the Soviet Union. International Wader Studies10: 9-12. A brief descriptionis givenof the developmentof wader studiesin the RussianEmpire, in the USSR,and currentlyin the CIS. Specialwader publications have appeared from the early20th century,but thesebirds only became a subjectof specialstudies since the late 1950s.Growth of interestin wadersin the 1960sculminated in All-Union wader conferencesorganised on an irregularbasis since 1973. In October1987 the WorkingGroup on Waderswas established,which keepsresearchers informed about wader studiesand relevantconservation activities not only in CIS but alsothroughout the world. However,almost no joint projectsare currentlyrunning successfullydue to low activityof the Groupmembers and their onlypartial interest in waders. P.S.Tomkovich, Ornithology Dept., Zoological Museum, Moscow State University, Bolshaya Nikitskaya Street, 6, Moscow 103009, Russia. TOMKOS•4u,II. C. t998. I4ccaeAosam4• no Kya•aM S COBeTCKOMColo3e. International Wader Studies 10: 9-12. Observations on waders in Russia, as on birds in A new wave of ornithologicalresearch began soon general,date from the secondhalf of the 18th after the Second World War, which was associated century.In the courseof numerousexpeditions an with the appearanceof the six-volumeBirds of the understandingof their numbersand distribution SovietUnion (Dementiev et al. 1951-54)and with acrossthe boundlessexpanses of the land beganto plansby the Academyof Sciencesof the USSRfor be obtained. This information was collated for the the preparationand publicationof monographson firsttime at the startof the presentcentury in the the fauna of little-studiedregions. Especially incompletemanuscript Waders of the Russian Empire worthy of notewas the volumeon wadersby O.B. -

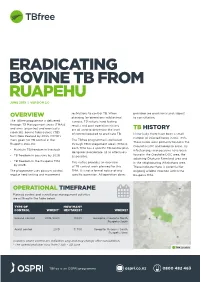

Eradicating Bovine Tb from Ruapehu June 2019 | Version 2.0

ERADICATING BOVINE TB FROM RUAPEHU JUNE 2019 | VERSION 2.0 restrictions to control TB. When provided are provisional and subject OVERVIEW planning for operations wild animal to consultation. The TBfree programme is delivered surveys, TB history, herd testing through TB Management areas (TMAs) results and past operation history and aims to control, and eventually are all used to determine the level TB HISTORY eradicate, bovine tuberculosis (TB) of control required to eradicate TB. Historically, there have been a small from New Zealand by 2055. OSPRI’s number of infected herds in this TMA. main goals for TB control in the The TBfree programme is delivered These herds were primarily found in the Ruapehu area are: through TB management areas (TMAs). Orautoha DOC and Horopito areas. TB Each TMA has a specific TB control plan • Maintain TB freedom in livestock infected pigs and possums have been designed to eradicate TB as effectively found in the Orautoha DOC area, the • TB freedom in possums by 2028 as possible. adjoining Ōhakune Farmland area and • TB freedom in the Ruapehu TMA This notice provides an overview in the neighbouring Whakahoro area. by 2028 of TB control work planned for this These indicate there is potential for The programme uses possum control, TMA. It is not a formal notice of any ongoing wildlife infection within the regular herd testing and movement specific operation. All operation dates Ruapehu TMA. OPERATIONAL TIMEFRAME Planned control and surveillance management activities are outlined in the table below. TYPE OF HOW MANY CONTROL WHEN?* HECTARES? WHERE? Ground control 2019/2020 9,000 Horopito, Orautoha North, Ruapehu South Aerial control 2019 31,700 Horopito, Ruapehu South, Ruapehu West Hectares under control are indicative only and may change after consultation. -

He Hīkoi Whakapono: a Journey of Faith

10 HUI-TANGURU 2019 NAUMAI Ngā Kōrero Feature WELCOM FEBRUARY 2019 11 He Hīkoi Whakapono: A Journey of Faith WelCom’s Hikoi of Faith returns to the Palmerston North Diocese as we continue to ‘Ruapehu Romans’ feature pastoral areas in the two dioceses. This year begins with a visit to Our Lady of the Joseph’s Primary School Taihape Merrilyn George Māori. This continues at the vigil for the PALMERSTON Snows Parish in the central North Island plateau area of Tongariro National Park and hill second Sunday each month on Maungarongo We have a dedicated Special Character team Pastoral worker Ann-Maree Manson-Petherick NORTH DIOCESE Marae. Our regular English Mass also has made up of Year 8 students. There are a variety country areas around Taihape. Our Lady of the Snows includes a number of churches and Principal communities from Ohakune, Raetihi, Waiouru, Taihape to Managaweka, several marae, many parts and music in Māori, thanks to the of activities they take part in both at school and While Europeans began settling on tussock skills of our music ministry. around the community, including supporting and St Joseph’s Catholic Primary School in Taihape. The district is renowned for year- land to graze sheep around Karioi in the There have been many changes over the years Our school is very fortunate to be located classes in class prayers and school liturgies; ARCHDIOCESE OF WELLINGTON round outdoor pursuits and is economically driven by tourism, farming, market gardening, 1860s (between Ohakune and Waiouru), the with property, buildings and personnel, but the just outside of Taihape amongst beautiful working alongside the junior students; baking forestry, and the Waiouru Military Camp and museum.