DO6MERT'resume Paperbackisbn-0-7914

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of Indiana Bell Includes Tricky Move

1 Sopamof 4/26/ 71 Quarterly D w tfe a * PofteN DeOectwa Skara Caver ad L ea n Savings laser ad ta M l MO law if Credit leaes Fiaaacial Caeaaafiai Cask m k t n m m S a ve ** Plan "People Helping People" Why tote it when you can stow it? Slow all that stuff you II need next fall at Pilgrim Self Service Storage over the summer For pennies a day. you can get rid of the bother of carrying it home and back again There s a Pilgrim mini-warehouse near you Call the resident manager for details 5425 N Tacoma Ave 3012 Glen Arm Road (North Keystone Area) (1-465 & 38th Street - 257-3354 West Side) 3350 N Post Road (North Eastwood Area) Southern Plan) 706-0871 6901 Hawthorne Park Drive 2251 N Shadetand Drive (South of 71st at S it 37) (1-70 & Shadetand) 049-1305 353-9411 ^ P i l g r i m SELF SERVICE STORAGE Tty $nti<luttw p e o p le Tty tin t name In rrWnl-werefKx/eee DALLAS/gORT WORTH/MID-CITIES HOUSTON/ATLANTA/INDIANAPOLIS PCS rate hearings will decide increase SANDER’S DELICATESSEN PvMIc Swvic* C H M te ta iMH m tt ttm State Offlct - I drtra Nr H U * fcraitap te — • u d > th» raquratad rate ‘— m i te IFALOO'a >ra>M«l rate, and cter «■ M ta M tta ta Prarar «ad U gM C te* |M NN|M nteiteraiiM ri;M pwy TM utility wUl praaral ite c*m- In duel in • (Muring tMgincung M*y I. -

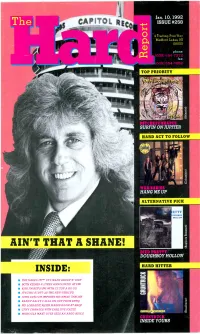

Ain't That a Shane!

Jan. 10, 1992 CAPITOL R ISSUE #258 0 4 Trading Post Way fai Medford Lakes, NJ 08055 phone: (609) 654-7272 fax: (ROMPR4-6852 TOP PRIORITY HARD ACT TO FOLLOW ALTERNATIVE PICK ',ETTY OUGHBOY 1101.1.0W AIN'T THAT A SHANE! INSIDE: HARD HITTER II THE NAKED CIT7' UTZ MADE GROUP W VEEP III BOTH KEINER & ..YKES ANNOUNCED AT EMI KISS FM RETURNS WITH ZZ TOP A GC GO IT'S ERIC STOTT AS THE NEW WXRC FD JOHN DUNTi-LN DEPARTS HIS WMAD THRONE IN RANDY RALEI. F )LLS ON OUT FROM KFMQ MD LORRAINE MCIER MAKES ROOM AT KRQF CFNY CHANGES KITH EARL JIVE JOLTED MISSOULA MA Kr OVER SEES AN ARGO ADIC S 0.111M11,1111 INSIDE YOURS NAG MANAGEMENT: ARTISTSHORIZON SERVICES ENTERTAINMENT CORP. Hard Hundred Lw Tw Artist Track LwTw Artist Track 1 1 U2 "Mysterious Ways" 32 51 Ozzy Osbourne "No More Tears" 2 2VAN HALEN "Right Now" 26 52The Who "Saturda Ni ht's ..." 4 3JOHN MELLENCAMP "Love And ..." >> D 53UGLY KID JOE "Everything About ..." 6 4BRYAN ADAMS "There Will Never ..." 62 54 U2 "Who's Gonna Ride..." 20 5GENESIS "I Can't Dance" 83 55 DIRE STRAITS "The Bug" 8 6NIRVANA "Smells Like Teen ..." >> D56 RTZ "Until Your Love ..." 18 7TOM PETTY "Kings Highway" 40 57 Lynyrd Skyrd "All I Can Do ..." 9 8 GUNS N' ROSES "November Rain" 63 58 GENESIS - "Jesus He Knows..." 12 9EDDIE MONEY "She Takes My ..." 66 59JAMES REYNE "Some People" 13 10BOB SEGER "Take A Chance" 69 60 DRAMARAMA "Haven't Got A ..." 10 11 METALLICA "The Unforgiven" 72 61 VINNIE MOORE "Meltdown" 3 12 Stevie Ray Vaughan "The Sky Is. -

Corpus Antville

Corpus Epistemológico da Investigação Vídeos musicais referenciados pela comunidade Antville entre Junho de 2006 e Junho de 2011 no blogue homónimo www.videos.antville.org Data Título do post 01‐06‐2006 videos at multiple speeds? 01‐06‐2006 music videos based on cars? 01‐06‐2006 can anyone tell me videos with machine guns? 01‐06‐2006 Muse "Supermassive Black Hole" (Dir: Floria Sigismondi) 01‐06‐2006 Skye ‐ "What's Wrong With Me" 01‐06‐2006 Madison "Radiate". Directed by Erin Levendorf 01‐06‐2006 PANASONIC “SHARE THE AIR†VIDEO CONTEST 01‐06‐2006 Number of times 'panasonic' mentioned in last post 01‐06‐2006 Please Panasonic 01‐06‐2006 Paul Oakenfold "FASTER KILL FASTER PUSSYCAT" : Dir. Jake Nava 01‐06‐2006 Presets "Down Down Down" : Dir. Presets + Kim Greenway 01‐06‐2006 Lansing‐Dreiden "A Line You Can Cross" : Dir. 01‐06‐2006 SnowPatrol "You're All I Have" : Dir. 01‐06‐2006 Wolfmother "White Unicorn" : Dir. Kris Moyes? 01‐06‐2006 Fiona Apple ‐ Across The Universe ‐ Director ‐ Paul Thomas Anderson. 02‐06‐2006 Ayumi Hamasaki ‐ Real Me ‐ Director: Ukon Kamimura 02‐06‐2006 They Might Be Giants ‐ "Dallas" d. Asterisk 02‐06‐2006 Bersuit Vergarabat "Sencillamente" 02‐06‐2006 Lily Allen ‐ LDN (epk promo) directed by Ben & Greg 02‐06‐2006 Jamie T 'Sheila' directed by Nima Nourizadeh 02‐06‐2006 Farben Lehre ''Terrorystan'', Director: Marek Gluziñski 02‐06‐2006 Chris And The Other Girls ‐ Lullaby (director: Christian Pitschl, camera: Federico Salvalaio) 02‐06‐2006 Megan Mullins ''Ain't What It Used To Be'' 02‐06‐2006 Mr. -

Catalogo ARTISTA TITULO for ANO OBS STOCK PVP

Catalogo ARTISTA TITULO FOR ANO OBS STOCK PVP 1927 ISH +2 CD 1989 20 th Anniversary Edition X 27,00 1927 THE OTHER SIDE CD 1990 AOR X 22,95 21 GUNS KNEE DEEP CDS 1992 Melodic Rock X 5,00 220 VOLT 220 VOLT CD Japanese Edition X 25,00 220 VOLT EYE TO EYE -Japan Edt.- CD 1988 Japan reissue remastered +2 tracks X 20,99 24 K PURE CD 2000 X 7,50 30 SECONDS TO MARS 30 SECONDS TO MARS CD X 17,95 38 SPECIAL FLASHBACK CD 1987 Best of 16,95 38 SPECIAL ICON CD 2011 Best of X 10,95 38 SPECIAL ROCK & ROLL STRATEGY CD 20,95 38 SPECIAL STRENGTH IN NUMBERS CD 1986 X 11,99 38 SPECIAL TOUR DE FORCE CD 1983 X 10,95 38 SPECIAL WILD-EYED SOUTHERN BOYS CD 1978 10,95 38 SPECIAL WILD-EYED SOUTHERN../SPECIAL FORCES CD 1978 1980 & 1982 2013 reissue 2 Albums 1 CD X 12,99 AB/CD CUT THE CRAO CD 12,95 AB/CD THE ROCK 'N''ROLL DEVIL CD 12,95 ABC THE CLASSIC MASTERS COLLECTION CD Best of X 12,95 AC/DC BACK IN BLACK CD 1980 2003 remastered X 14,95 AC/DC BACK IN BLACK -LTD 180G- CD 1980 2009 LTD 180G X 22,95 AC/DC BALLBREAKER CD 12,95 AC/DC BLACK ICE CD 2008 Remasters digipack X 17,95 AC/DC BONFIRE 5CD X 27,95 AC/DC DIRTY DEEDS DONE DIRT CHEAP 4DVD X 25,00 AC/DC DIRTY DEEDS DONE DIRT CHEAP CD 1976 Remasters digipack 9,95 AC/DC FLICK OF THE SWITCH CD 12,95 AC/DC FLY ON THE WALL CD 12,95 AC/DC HELL AIN'T A BAD PLACE TO BE BOOK X 8,95 AC/DC HIGHWAY TO HELL CD 12,95 ARTISTA TITULO FOR ANO OBS STOCK PVP AC/DC HIGHWAY TO HELL -180G- LP 1979 2009 ltd 180G X 22,95 AC/DC IF YOU WANT BLOOD YOU'VE GOT IT CD 12,95 AC/DC IN CONCERT BLRY 2012 98 min X 12,95 AC/DC IT''S A LONG WAY TO THE TOP DVD X 7,50 AC/DC LET THERE BE ROCK DVD X 10,95 AC/DC LIVE 92 2LP 1992 Live X 25,95 AC/DC LIVE 92 2CD 1992 Live X 24,95 AC/DC NO BULL DVD X 12,95 AC/DC POWERAGE CD 10,95 AC/DC RAZOR'S EDGE CD 1990 Remasters digipack X 14,95 AC/DC STIFF UPPER LIP CD Remasters digipack 10,95 AC/DC T.N.T. -

Ellsworth American COUNTY America* : Ffgjf.‘O Advaccw CORNER OPPOSITE the POSTOFFICE

worth mertcatt » SUBSCRIPTION PER PRICK, $2.00 TEAR. > ENTERED AS SECOND* CLASS MATTER LI. * 19 PAID (M ADVANCE, $I.M. | f 1XKJ,"NTri U\J90 Vol. ELLSWORTH, MAINE. WEDNESDAY AFTERNOON, MAY 17, f AT THE ELLSWORTH POSTOFPICK. { abufTtiftcmenif. LOCAL AFFAIRS. though not members, who have an interest of the second part. The affair was under JUHjcrttscmnus. in the perpetuation of the Maine music the direction of Mrs. E. J. Walsh and Mrs. festivals. F. M. whose efforts NKW ADVKRTIKBJtfKNrH T IIH WEEK Gaynor painstaking Another yacht has been sold from the were amply rewarded by the complete ft is Tru-t Cu— Notice of foreclosure. Metropolitan Union river fleet—the owned success of th" affair. Miss Nan I. Drum- In bankruptcy-K-t Willard I* smith Empress, by was selections were Hancock Liquor l ml let me lit* Alec »D. Stuart. Last week Mr. Stuart mey accompanist, and Cdin^y Probate notice- K-t Hmyton M Perkins. sold the at intervals orches- to Dr. of played by Monaghan’s Ailmr notice-E*t M» In»w« L I’erklM. Empress Montgomery, Artlttr noth* —K*i Carol I in* Smith. Boston, a summer resident of East Blue- tra. After the concert the floor was l’r bate notlC'-K.-is ^Arnh L Mascyetal*. j hill. cleared for dancing, which was kept up In linnkrupiry — E»t thus W Harper. until about 12 o’clock. Ex*c notle.H—Kft Joseph If .loh >sofi. E. F. is back from Boston Bank. A It Robinson, jr., trim'll son—Cow for sate. Last Nokomia Rebekah Savings IMo-htU A Swan’s Islam! steam where he has been taking a two-months’ evening lodge KtUworth, boat llm*. -

Record-Mirror-1978-1

November 25 1978 1Bp ic o " ES3 - .e, 4N!JAPfr'1 1AKrA L á SH? rr t ROD STEWART IN COLOUR MIKE OLDFIELD PATRICK JUVET PERE UBU BRUCE SiRINGSTEEN '. VOTE IN THE POLL 0 eteCOIO Mirror, NOvember 25, 19/3 5t 1 1 SIN RAT TRAP, UKBmmown Rats Ensign UKAL8utss 2 2 HOPELESSLY USALBUMS DEVOTED TO YOU Okv.a Newton 1 1 U5sINcis John RSO GREASE Ongmnl Soundtrack ESO 1 1 52nd STREET B.tly Joe Ceunem 3 St MY REST FRIENDS GIRL Cars 1 1 Elektra 2 - GIVE 'EM ENOUGH ROPE, The Clash CBS MAC ARTHUR PARK, Donna Summer J. Webb 2 2 LIVE AND MORE. Donna Summer Casablanca 4 DO to VA THINK 1'M SEXY, Rod Stewart 2 2 DOUBLE VISION, Foreigner VISION. Forergner R,va 3 2 EMOTIONS, Var,om K -Tel pP Adanuc 3 3 DOUBLE Ananhc 5 7 PRETTY LITTLE ANGEL 3 EYES, Shnwaddywaddn Anota 4 11 LIVE, Manhattan Transfer Atlantic 3 HOW MUCH ( FEEL Ambrosia Warner Bros 4 8 A WILD AND CRAZY GUY, Steve Martin Warder Bros 6 6 DARLAN Franke, Maier 4 Chrvsaln 5 3 25th ANNIVERSARY ALBUM. ShIrley Basses Untied Mists 5 YOU DON'T BRING ME FLOWERS, 5 5 GREASE. Soundtrack RSO 7 3 SUMMER NIGHTS. John TravaltatOlivia THE LUrrda Ronsradt Asylum Newton -John RSO 6 5 NIGHTFLIGHT TO VENUS, Bonee M Atlantic/Hansa Barbra Stmisand 6 Neil Diamond Columbra , 6 4 UVING IN USA. 8 e INSTANT REPLAY. Dan Hartman 5 4 Styx A8M Blue Sky 7 - 20 GOLDEN GREATS, Nell Diamond MCA YOU NEEDED ME. Anne Muiray Capitol 7 7 PIECES OF EIGHT. -

10/02/2017 Catalogo Page 1 ARTISTA TITULO for ANO 1927

Catalogo 10/02/2017 ARTISTA TITULO FOR ANO 1927 ISH +2 CD 1989 1927 THE OTHER SIDE CD 1990 21 GUNS KNEE DEEP CDS 1992 220 VOLT 220 VOLT CD 220 VOLT EYE TO EYE -Japan Edt.- CD 1988 24 K PURE CD 2000 30 SECONDS TO MARS 30 SECONDS TO MARS CD 38 SPECIAL FLASHBACK CD 1987 38 SPECIAL ICON CD 2011 38 SPECIAL ROCK & ROLL STRATEGY CD 38 SPECIAL STRENGTH IN NUMBERS CD 1986 38 SPECIAL TOUR DE FORCE CD 1983 38 SPECIAL WILD-EYED SOUTHERN BOYS CD 1978 38 SPECIAL WILD-EYED SOUTHERN../SPECIAL FORC CD 1978 A*TEENS TEEN SPIRIT CD 2001 AB/CD CUT THE CRAO CD AB/CD THE ROCK 'N''ROLL DEVIL CD ABC THE CLASSIC MASTERS COLLECTION CD ABIOGENESI LE NOTTI DI SALEM CD AC/DC BACK IN BLACK CD 1980 AC/DC BACK IN BLACK -LTD 180G- CD 1980 AC/DC BALLBREAKER CD AC/DC BLACK ICE CD 2008 AC/DC BONFIRE 5CD AC/DC DIRTY DEEDS DONE DIRT CHEAP CD 1976 AC/DC DIRTY DEEDS DONE DIRT CHEAP 4DVD AC/DC FLICK OF THE SWITCH CD AC/DC FLY ON THE WALL CD AC/DC HELL AIN'T A BAD PLACE TO BE BOOK AC/DC HIGHWAY TO HELL CD AC/DC HIGHWAY TO HELL -180G- LP 1979 AC/DC IF YOU WANT BLOOD YOU'VE GOT IT CD AC/DC IN CONCERT BLRY 2012 AC/DC IT''S A LONG WAY TO THE TOP DVD AC/DC LET THERE BE ROCK DVD AC/DC LIVE 92 2CD 1992 AC/DC LIVE 92 2LP 1992 AC/DC MIX =SHOT GLASS= MERC AC/DC NO BULL DVD AC/DC POWERAGE CD AC/DC RAZOR'S EDGE CD 1990 AC/DC STIFF UPPER LIP CD AC/DC T.N.T.