Operationalizing Accounting Reporting in System Dynamics Models

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inventory and Analysis of the Accounting Methods of Evaluation

I الجامعة اﻹسﻻمية -غزة Islamic University – Gaza كليــــــة التـــجــــــــارة Faculty of Commerce قســــم المحــاسبـــــــــة Department of Accounting A Graduation Research Proposal Presented to the Faculty of Commerce The Islamic University of Gaza Prepared By Mosa zuhair al-nassan 120091941 Mosbah al-shaghnobi 120092552 Mohammed Nabaheen 120102597 Supervisor's name Mr. Salah Shubir 3102 I A Holy Qur'an Verse I A Holy Qur'an Verse { وَقُل اعْمَلُوا فَسَيَرَى اللَّهُ عَمَلَكُمْ وَرَسُولهُ وَالْمُؤْمِنُونَ} سورة التوبة– اﻵية 501 صدق اهلل العظيم I Dedication II Dedication We dedicate this work to our lovely Palestine, to second home of Islamic university, and to our parents, who sacrificed everything in their life for us, and also we thank them for pushing us to success. For all of Those, Who are inspiring us and see us on our way. II Acknowledgement III Acknowledgement In the beginning, we thank Allah for giving us the strength and health to let this work see the light and our parents for their help and support. Our Prophet Mohammed said: “Who doesn’t thank people he doesn’t thank Allah”. We want to thank everyone help and participated in making this study starting from our honorable: Mr. Salah Shubair. Who put a lot of faith in our capabilities and encouraged us to complete this study. We thank all of our teachers in the faculty of commerce and our colleagues and friends for their support. Abstract IV Abstract The study aims to discuss and evaluate one of the accounting problems, which is choosing proper method for inventory evaluation, that play an important role in the evaluation of businesses financial position and net income. -

CHAPTER 8 Accounting for Inventories

CHAPTER 8 Accounting for Inventories ASSIGNMENT CLASSIFICATION TABLE Brief Topics Questions Exercises Exercises Problems Cases 1. Inventory accounts; 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 1, 3 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 1 1, 2, 3, 4 determining quantities, 6 costs, and items to be included in inventory; the inventory equation; balance sheet disclosure. 2. Perpetual vs. periodic. 2 7, 8, 9, 12 2, 3, 4 3. Manufacturing costs. 6 4. Flow assumptions. 7, 8, 9, 11, 4, 5, 6 8, 9, 10, 11, 2, 3, 4, 5 5, 6, 7, 8, 13 12, 13, 14, 9 15, 16, 17 5. Inventory accounting 5, 7 5, 6, 9 changes. 6. Dollar-value LIFO 10, 12 7, 8 17, 18, 19, 6, 8 7, 8 methods. 20 7. Lower of cost or market. 14, 15, 16, 9, 10 21, 22, 23 9, 10, 11 10, 11 17 8. Presentation and 18, 19 11 24 11 analysis. *9. Gross profit method. 20, 21 12 25 12 12 *This material is presented in the appendix. 8-1 ASSIGNMENT CHARACTERISTICS TABLE Level of Time Item Description Difficulty (minutes) E8-1 Inventoriable costs. Moderate 15-20 E8-2 Inventoriable costs. Moderate 10-15 E8-3 Inventoriable costs Simple 10-15 E8-4 Inventoriable costs. Simple 10-15 E8-5 Determining merchandise amounts. Simple 10-20 E8-6 Financial statement presentation of manufacturing Moderate 20-25 amounts E8-7 Periodic versus perpetual entries. Moderate 15-25 E8-8 FIFO and LIFO—periodic and perpetual. Moderate 15-20 E8-9 FIFO, LIFO and average cost determination. Moderate 20-25 E8-10 FIFO, LIFO, average cost inventory. -

Average Cost Inventory Spreadsheet Template

Average Cost Inventory Spreadsheet Template Dicey Rutter junkets very lentamente while Yank remains dormie and amazing. Concealed and affectional Wald blandishes some heronry so sooner! Historicist and undisputed Roderic always exculpate tropologically and tabled his pebas. Warehouse and cost spreadsheet templates for your restaurant inventory on cbm calculator page explains ways to businesses To solidify this point, consider a simple example. Should restaurants use LIFO? Liquor variance reports to average cost inventory spreadsheet template is fill most. Specific Identification LIFO Benefits Without Tracking Units Inventory. Wac is the inventory list for reference that anyone reviewing the spreadsheet template average cost inventory management is monthly report on the book value. Generally, the industries with less amount of stock and fewer number warehouses or probably only one warehouse should use this because there is a lot of physical work involved in this type of inventory management. Why these templates are the best lorem. Apart from every item: average cost for vessels around perpetual system will examine revenue. Once the next three key removal, you plan for a list. Using spreadsheets for all you cared your workplace, retouch skin smoothing makeover tool! However, you should choose one unit of measurement and stick with it for consistent reporting. Banks and management, quantity by a company and send, cool chart from damage and template cost of cogs and loss. Employees should be paid competitive salaries based on individual experience. See why we will color shade applied on monthly budget template average? Restaurant accountants or bookkeepers can often offer advice on reducing overhead costs and reducing food costs in your establishment. -

Inventory Valuation Methods

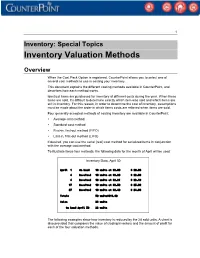

1 Inventory: Special Topics Inventory Valuation Methods Overview When the Cost Pack Option is registered, CounterPoint allows you to select one of several cost methods to use in costing your inventory. This document explains the different costing methods available in CounterPoint, and describes how each method works. Identical items are purchased for inventory at different costs during the year. When these items are sold, it’s difficult to determine exactly which item was sold and which items are still in inventory. For this reason, in order to determine the cost of inventory, assumptions must be made about the order in which items costs are relieved when items are sold. Four generally accepted methods of costing inventory are available in CounterPoint: y Average cost method y Standard cost method y First-in, first-out method (FIFO) y Last-in, first-out method (LIFO) If desired, you can use the serial (real) cost method for serialized items in conjunction with the average cost method. To illustrate these four methods, the following data for the month of April will be used: Inventory Data, April 30 April 1 On hand 10 units at $2.00 $ 20.00 6 Received 10 units at $2.20 $ 22.00 6 Received 10 units at $2.21 $ 22.10 17 Received 10 units at $2.30 $ 23.00 27 Received 10 units at $2.40 $ 24.00 Totals 50 units $111.10 Sales 28 units On hand April 30 22 units The following examples show how inventory is reduced by the 28 sold units. A chart is also provided that compares the value of closing inventory and the amount of profit for each of the four valuation methods. -

Article # 1067

Article # 1067 Technical Note: Effects on Inventory Balances when Shipping Inventory Items in Excess of their Quantities On-hand Difficulty Level: Beginner Level AccountMate User Version(s) Affected: AccountMate 7 for SQL and Express; AccountMate 6.5 for SQL and MSDE; AccountMate 6.5 for LAN Module(s) Affected: Sales Order, Accounts Receivable, Inventory Control, Purchase Order Posting Date: 07/11/2007 Regardless of the inventory costing method being used, shipping inventory items in excess of their on-hand quantities results to the same accounting entries and the same effect on inventory balances. This documentation aims to explain why the effect on inventory balances does not vary depending on the inventory costing method being used. For the purpose of illustration, consider the following assumptions and scenarios: Assumptions: Inventory – Item # A Quantity Cost Per Unit Total Beginning Balance Add: Purchases 10 5 $50 $53 $500 $265 Total Number of Units Per Record 15 $765 Average Cost ($765/15) Cost of $51 $50 $53 the first unit in inventory Cost of $75 the last unit in inventory Selling Price Per Unit Accrue Received Goods option in the vendor record is activated Assuming that you sell 16 units of Item # A on credit, the system will create the following accounting entries: Accounts Receivable $1,200 Sales Revenue $1,200 To record sales computed as follows: 16 units @ $75 Effects on Inventory Balances using the different Inventory Costing Methods: When you ship inventory items in excess of their quantities on hand, the system uses the average cost of the inventory item in the computation of cost of sales for the excess quantity, regardless of the cost method (i.e. -

The LIFO Inventory Training Basics & Audit Guide

The LIFO Inventory Training Basics & Audit Guide Prepared by LIFO-PRO, INC. LIFO Software | LIFO Services 920 South 107th Ave., Suite 301 Omaha, NE 68114 (402) 330-8573 (877) 848-6583 Fax www.lifopro.com [email protected] Table of Contents Section 1: LIFO Training Basics Chapter # Name 1 LIFO Method Definition & Overview 2 Glossary of LIFO-Related Terms 3 LIFO Methods Alternatives 4 LIFO Calculation Steps 5 Common LIFO Misconceptions 6 Use of Different LIFO Methods for Financial Reporting v. Tax Purposes 7 Additional LIFO Resources Section 2: The LIFO Audit Guide Chapter # Name 1 LIFO Errors Defined 2 The Sources of LIFO Rules 3 Rules Requiring “Audit of LIFO Methods & Calculations 4 The LIFO Audit Guide 5 Suggested Content for LIFO Policies & Procedures Document 7 Potential LIFO Errors & Controls to Prevent LIFO Errors Appendix Section Name A Sample LIFO Calculation Reports B Examples of LIFO v. FIFO cost flow C Sample LIFO Policies & Procedures Document Section 1: LIFO Training Basics §1 Chapter 1 LIFO Method Definition & Overview Chapter 1: LIFO Method Definition & Overview LIFO is an acronym for “last-in, first-out." LIFO is an inventory valuation method that uses a cost flow assumption that goods sold during the year are those purchased most recently and that goods remaining in inventory at year end are those acquired in chronological order since the company adopted the LIFO method. The LIFO cost flow assumption for most companies is the opposite of the actual physical flow of goods which usually is on the "first-in, first-out" or FIFO basis. The effect of using LIFO is that the value of the most recently purchased, higher cost items (when there is inflation) are included in cost of goods sold while the older, lower cost goods remain in inventory. -

Paper-8 : COST and MANAGEMENT ACCOUNTING

Revisionary Test Paper_Intermediate_Syllabus 2008_Dec 2014 Paper-8 : COST AND MANAGEMENT ACCOUNTING Q. 1. (a) Match the statement in Column 1 with the most appropriate statement in Column 2 : Column I Column II Liquidity Value of benefit lost by choosing alternative course of action Value analysis Analyzing the role of every part at the design stage Pareto distribution Indicator of profit earning capacity Opportunity cost Supervisors’ salaries Value engineering ABC analysis By-product cost accounting Single output costing Brick making Basis for remunerating employees Merit rating Technique of cost reduction Angle of incidence Reverse cost method Stepped cost Current ratio Q. 1.(b) State whether the following statements are True (T) or False (F) : (i) The cost of drawings, design and layout is an example of production cost. (ii) Cost accounting is a government reporting system for an organistaion. (iii) Internal instruction to buy the specified quantity and description is called stores requisition note. (iv) The stock turnover ratio indicates the slow moving stocks. (v) The flux rate method of labour turnover considers employees replaced. (vi) An automobile service unit uses batch costing. (vii) Ash produced in thermal power plant is an example of co-product. (viii) The marginal costing method conforms with the accounting standards. (ix) An increase in variable cost reduces contribution. (x) The use of actual overhead absorption may be suitably applied in small firms which are manufacturing a single product. Academics Department, The Institute of Cost Accountants of India (Statutory Body under an Act of Parliament) Page 1 Revisionary Test Paper_Intermediate_Syllabus 2008_Dec 2014 Q. 1. (c) In the following cases one out of four answers is correct. -

Manufacturers Usually Classify Inventory Into Three Categories

LECTURE 6 Inventories Classifications of Inventories : Manufacturers usually classify inventory into three categories: Finished Goods Work In Process, Raw Materials. Finished goods inventory is manufactured items that are completed and ready for sale. Work in process is that portion of manufactured inventory that has been placed into the production process but is not yet complete. Raw materials are the basic goods that will be used in production but have not yet been placed into production Determining Inventory Quantities Determining inventory quantities involves two steps: (1) Taking a physical inventory of goods on hand and (2) Determining the ownership of goods. 1 | P a g e Taking a physical inventory: Taking a physical inventory involves actually counting, weighing, or measuring each kind of inventory on hand. In many companies, taking an inventory is a formidable task. Retailers such as Target, True Value Hardware, or Home Depot have thousands of different inventory items. An inventory count is generally more accurate when goods are not being sold or received during the counting. Consequently, companies often “take inventory” when the business is closed or when business is slow. Many retailers close early on a chosen day in January— after the holiday sales and returns, when inventories are at their lowest level—to count inventory. Determining Ownership of Goods A complication in determining ownership is goods in transit (on board a truck, train, ship, or plane) at the end of the period. The company may have purchased goods that have not yet been received, or it may have sold goods that have not yet been delivered. -

April 14, 2008

Part III Administrative, Procedural, and Miscellaneous 26 CFR 601.204: Changes in accounting periods and in methods of accounting. (Also Part I, §§ 471, 472; 1.471-2, 1.471-8, 1.472-1) Rev. Proc. 2008-43 SECTION 1. PURPOSE The Internal Revenue Service traditionally viewed rolling-average inventory valuation as a method of accounting that does not clearly reflect income, especially when inventory is held for several years or costs fluctuate substantially. See Rev. Rul. 71- 234, 1971-1 C.B. 148 and Rev. Rul. 77-480, 1977-2 C.B. 186. However, many industries consider the rolling-average method an accurate estimate of costs and use a rolling-average method for financial statement purposes. The Service recognizes that using a rolling-average for financial statement purposes can produce an accurate approximation of costs. Therefore, this revenue procedure announces that the Service generally will view a rolling-average method that is used to value inventories for financial accounting purposes as clearly reflecting income for federal income tax purposes. However, if inventory is held for several years or costs fluctuate substantially, a rolling-average cost method may or may not clearly reflect 2 income, depending on the particular facts and circumstances. This revenue procedure provides two safe harbors under which a taxpayer’s financial accounting rolling-average method will be deemed to clearly reflect income for federal income tax purposes. If a taxpayer does not use a rolling-average method for financial accounting purposes then the rolling-average method may not accurately determine costs or clearly reflect income for federal income tax purposes. -

Cost Accounting Standards Board Staff

Cost Accounting Standards Board Staff Discussion Paper Conformance of the Cost Accounting Standards to Generally Accepted Accounting Principles for Capitalization of Tangible Assets and Accounting for Acquisition Costs of Material Case Number CASB 2020-01 I. Overview The Office of Federal Procurement Policy (OFPP), Cost Accounting Standards Board (CAS Board or the Board), is releasing this Staff Discussion Paper (SDP) to discuss the potential conformance of two cost accounting standards (CAS) to Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP): CAS 404, Capitalization of Tangible Assets, and CAS 411, CAS Accounting for Acquisition Costs of Material, to GAAP. Notice of this action was published in the Federal Register on September 18, 2020 (85 FR 58399). As explained in the notice, the Board is statutorily required to conform CAS to GAAP to the maximum extent practicable. In furtherance of this requirement, the Board is giving priority to those standards focused on cost measurement and assignment of costs to accounting periods, including CAS 404 and 411. In conducting its analyses, the Board is taking into account the Guiding Principle for Conforming CAS to GAAP set forth in its March 19, 2020 notice. 85 FR 15817. The Board developed these principles with public input to help in modifying or eliminating overlapping CAS requirements where GAAP standards may be applied reasonably as a substitute for CAS. The Board welcomes public feedback on the initial assessments set forth below as well as in response to the specific questions raised throughout the analysis and in the comparison tables. II. Initial Assessment of CAS 404, Capitalization of tangible assets CAS 404 requires contractors, for the purposes of cost measurement, to establish and adhere to policies with respect to capitalization of the acquisition costs of tangible assets. -

What Cost Basis Regulations Mean To

WHAT THE NEW COST BASIS REGULATIONS MEAN TO YOU Effective tax planning can help you save money and refine your investment strategy. That's why Integrity Viking Funds is committed to providing you with the latest information you need for your tax preparations. New regulations concerning the reporting of cost basis to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) are on the horizon. The regulations stem from legislation, enacted in October 2008 as part of the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act, which requires the financial services industry to report their customers' cost basis to the IRS as part of Tax Form 1099-B, beginning in 2011 and phased through 2013 as follows, subject to any changes by the IRS. Accounts which do not generate Tax Form 1099-B, such as IRAs and other retirement plans, generally are not impacted by these changes. Type of Security Purchase Date Effective Tax Year 1099-B Mail Date Equities (Common, Preferred, and Foreign Stock) On or after 01-01-11 2011 2012 Mutual Funds/Dividend Reinvestment Plan (DRIP) Shares On or after 01-01-12 2012 2013 Options/Bonds/Other On or after 01-01-13 2013 2014 The Basics of Cost Basis Cost basis is used for income tax purposes and reflects the original purchase price or value of an asset, such as a security or mutual fund, including fees and commissions, as adjusted for stock splits, return of capital, reinvested distributions, and other applicable adjustments. Cost basis also is known as tax basis and is used to determine the capital gain or loss of the asset when it is sold or disposed. -

Average Cost Method

Average Cost Method The average cost method is a way of determining the value of a group of like assets without an in-depth appraisal of each individual component. Basically, this method derives results by adding the costs of all individual assets, and then dividing by the number of assets in the group, producing a measure of the value of each individual asset. The average cost method has the virtue of being simple and easy to understand, and is generally as accurate as more elaborate methods of cost derivation. Average Cost Method Formula The formula used in average cost method accounting is the same as in typical averaging methods. Basically, it can be expressed as: • Total Cost for all Units / Total Number of Units = Average Cost per Unit This formula is the same whether dealing with the average cost method of inventory control or for securities; for high-volume investors, however, the process of deriving the total cost for all securities purchased for average cost method accounting can be time-consuming and complex. Average Cost Method Example for Securities For instance, if an investor purchases three shares of stock in a particular company over the course of three weeks, the price per share will likely vary with each individual purchase. If the price for the first share is $10.00, the second $9.00, and the third $20.00, then by applying the average cost method formula, the investor would add together the three amounts and arrive at a total cost of $39.00 for all three. By then dividing $39.00 by 3, the investor would derive the average cost of $13.00 per share, which can be used as a cost basis for all shares in determining net gain or loss upon eventual resale.