Harry Potter's Heroics: Crossing the Thresholds of Home, Away, and the Spaces In-Between Mary D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis on Moral Valuesof Harry Potter and the Philosopher’S Stone Novel

AN ANALYSIS ON MORAL VALUESOF HARRY POTTER AND THE PHILOSOPHER’S STONE NOVEL Khairunnisa, Albert Rufinus, Eusabinus Bunau English Education Study Program of Teacher Training and Education Faculty of Tanjungpura University, Pontianak Email: [email protected] Abstract The main focus of this research is to find out the moral values of the novel “Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone” by J.K. Rowling based on the major characters. Major characters are the most important actors or people in the novel and they are Harry Potter, Hermione Granger, Ron Weasley, Albus Dumbledore, Hagrid and Professor Snape. One of the key factors that distinguish character from personality is called moral values. Moral values are the things right or wrong in the story which refer to the behavior and the attitude of characters that is giving advices or lessons. The researcher had conducted this research by applying descriptive qualitative method, for describing manner or behavior through quotation of speech or dialogue and action. According to the result, there are some moral values found in this novel, they are courage, cleverness, friendly, kindness, patient, politeness, responsibility, self- dicipline, trusworthiness, and wisdom. Those moral values above, can be applied in teaching and learning process, especially for the students in English Education Study Program. Keywords: Analysis, Moral values, Novel INTRODUCTION means ‘tale’, or ‘piece of news’. According Literature is an aesthetic aspect that to Griffith (1982) there are intrinsic gives pleasure and qualifies appreciation of elements that build the novel and make it human personal imagination toward life, into a solid story. They are character, expressing thought, and feeling. -

Many Faces of Albus Dumbledore in the Setting of Fan Writing

MANY FACES OF ALBUS DUMBLEDORE IN THE SETTING OF FAN WRITING: THE TRANSFORMATION OF READERS INTO “READER-WRITERS” AND THE IMPLICATIONS OF THEIR PRESENCE IN THE AGE OF ONLINE FANDOM by Midori Fujita A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in The Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies (Children’s Literature) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) October 2014 © Midori Fujita, 2014 ii Abstract This thesis examines the dynamic and changing nature of reader response in the time of online fandom by examining fan reception of, and response to, the character Dumbledore in J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series. Using the framework of reader reception theory established by Wolfgang Iser, in particular Iser’s conception of textual indeterminacies, to construct my critical framework, this work examines Professor Albus Dumbledore as a case study in order to illuminate and explore how both the text and readers may contribute to the identity formation of a single character. The research examines twenty-one selected Internet-based works of fan writing. These writings are both analytical and imaginative, and compose a selection that illuminates what aspect of Dumbledore’s characters inspired readers’ critical reflection and inspired their creative re-construction of the original story. This thesis further examines what the flourishing presence of Harry Potter fan community tells us about the role technological progress has played and is playing in reshaping the dynamics of reader response. Additionally, this research explores the blurring boundaries between authors and readers in light of the blooming culture of fan fiction writing. -

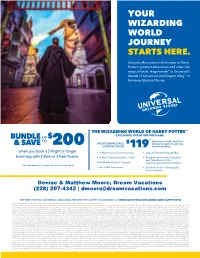

Your Wizarding World Journey Starts Here

YOUR WIZARDING WORLD JOURNEY STARTS HERE. Step into the excitement of some of Harry Potter's greatest adventures and enter two magical lands: Hogsmeade™ in Universal's Islands of Adventure and Diagon Alley™ in Universal Studios Florida. THE WIZARDING WORLD OF HARRY POTTER™ ^ EXCLUSIVE VACATION PACKAGE BUNDLE UP $ TO per person, per night, based on a & SAVE VACATION PACKAGE $ family of four with a 5-night stay, 200 STARTING FROM 119 limited availability. when you book a 2-Night or longer • 5-Night Hotel Accommodations • Special Themed Keepsake Box§ hotel stay with 2-Park or 3-Park Tickets. • 2-Park 5-Day Park-to-Park Ticket1 • Breakfast at the Leaky Cauldron™ and Three Broomsticks™ • $75 Bundle & Save^ Discount (one per person at each location) ^Savings based on 7-night stay. Restrictions apply. • Early Park Admission2 • Shutterbutton’s™ Photography Studio Session8 Denise & Matthew Moore, Dream Vacations (228) 207-4342 | [email protected] BEFORE VISITING UNIVERSAL ORLANDO, REVIEW THE SAFETY GUIDELINES AT WWW.UNIVERSALORLANDO.COM/SAFETYINFO WIZARDING WORLD and all related trademarks, characters, names, and indicia are © & ™ Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. Publishing Rights © JKR. (s21) All prices, package inclusions & options are subject to availability and to change without notice and additional restrictions may apply. Errors will be corrected where discovered, and Universal Orlando and Universal Parks & Resorts Vacations reserve the right to revoke any stated offer and to correct any errors, inaccuracies or omissions, whether such error is on a website or any print or other advertisement relating to these products and services. ^Bundle and Save offer discount only applies to Universal Orlando vacation packages purchased on Universal Parks & Resorts Vacations websites (UniversalOrlando.com, UniversalOrlandoVacations.com, VAXVacationAccess.com/UPRV), the Universal Orlando Guest Contact Center or through travel agencies registered to sell vacation packages with Universal Parks & Resorts Vacations. -

Wizarding Hierarchy

English University of Iceland School of Humanities English Wizarding Hierarchy A Portrayal of Discrimination and Prejudice in J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter novels B.A. Thesis Sigríður Eva Þorsteinsdóttir Kt.: 020696-3549 Supervisor: Valgerður Guðrún Bjarkadóttir May 2018 Abstract This paper explores how the Harry Potter novels by J.K. Rowling touches on the subject of discrimination and general prejudice against minority groups throughout the history of mankind. Though there are many minority groups in the novels, only a few will be discussed. Each of them will be compared to minority groups that faces prejudice in the real world. The paper further examines the effect discrimination has on the wizarding world and the struggle that wizards have to face to break from old habits, such as the enslavement of house-elves and their ongoing quarrels with goblins and other non-human creatures. The history of these feuds will be discussed as well as possible ways of mending the relationship between wizards and the minority groups. Oppression and abuse towards these minority groups are parts of the daily life of wizards and has been for centuries. Likewise, there will a focus on the prejudice werewolves face and how they mirror HIV infected people. In order to compare werewolves and people with HIV, a series of articles and studies on attitude towards diseases such as HIV/AIDS will be analyzed. The paper will also include a discussion about a few characters from the series that in some way are connected to minority groups: Hermione Granger, Harry Potter, Ron Weasley, Dolores Umbridge, Lord Voldemort, Dobby the house- elf, and lastly the werewolf Remus Lupin. -

"Leakycon Radio" Dedicated to Harry Potter Fans to Launch on Siriusxm

"LeakyCon Radio" Dedicated to Harry Potter Fans to Launch on SiriusXM Limited-run tribute channel transports fans into the world of Harry Potter from every angle as the final installment of the beloved and critically acclaimed film series hits theaters Nonstop coverage of the world's largest gathering of Harry Potter fans Channel also features interviews with Daniel Radcliffe, Emma Watson, Rupert Grint and other key players NEW YORK, July 12, 2011 /PRNewswire/ -- Sirius XM Radio (NASDAQ: SIRI) today announced that it will launch "LeakyCon Radio," a three-day channel that will celebrate the world of Harry Potter and pay tribute to its fans as the final film in the beloved series hits theaters. (Logo: http://photos.prnewswire.com/prnh/20101014/NY82093LOGO ) "LeakyCon Radio" premieres Friday, July 15 at 6:00 am ET — the day Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part 2 hits theaters — and airs through Monday, July 18 at 3:00 am ET on SiriusXM channel 141 and SiriusXM Internet Radio. Hosted by SiriusXM's Paul Bachmann and Kenny Curtis, the channel will broadcast from LeakyCon 2011, the Harry Potter fan convention taking place in Orlando, FL. "LeakyCon Radio" offers listeners a front row seat to the wide variety of panels and special events taking place throughout the weekend at the convention, including: Death Eater Recruitment and Training Jeopardy - Harry Potter and the Law; The Books vs. The Movies: What Was Left Out and Why It's Important; Fantastic Names & Where to Find Them: Lessons of Onomatology in Rowling's Harry Potter Series; The Past, Present, and Future of Muggle Quidditch; Cooking Demonstration: Butterbeer 101 and Bertie Botts Every Flavor Bean; and ...Now What? Life in the Potter fandom post Deathly Hallows: Part 2. -

Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone Discussion Guide

DISCUSSION GUIDE and the Philosopher’s Stone DISCUSSION GUIDE ABOUT THE HARRY POTTER BOOKS AND THIS GUIDE J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter books are among the most popular and acclaimed of all time. Published in the UK between 1997 and 2007 and beginning with Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, the seven books are epic stories of Harry Potter and his friends as they attend Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry. Crossing genres including fantasy, thriller and mystery, and at turns exhilarating, humorous and sad, the stories explore universal human values, longings and choices. The Harry Potter books are compelling reading for children and adults alike; they have met phenomenal success around the world and have been translated into 77 languages. A whole generation of children grew up awaiting the publication of each book in the series with eager anticipation, and they still remain enormously popular. The Harry Potter books make excellent starting points for discussion. These guides outline a host of ideas for discussions and other activities that can be used in the classroom, in a reading group or at home. They cover some of the main themes of the series, many of which, while set in an imaginary world, deal with universal issues of growing up that are familiar to all children. You will also find references to key moments on pottermore.com, where you can discover more about the world of Harry Potter. These guides are aimed at stimulating lively discussion and encouraging close engagement with books and reading. We hope you will use the ideas in this guide as a basis for educational and enjoyable work – and we think your group will be glad you did! Visit harrypotterforteachers.com for more Harry Potter discussion guides and reward certificates 2 and the Philosopher’s Stone DISCUSSION GUIDE INTRODUCTION TO HARRY POTTER AND THE PHILOSOPHER’S STONE Harry Potter has been raised by his horrible relatives, Uncle Vernon and Aunt Petunia, who treat him with disdain while lavishing attention on their spoiled son, Dudley. -

Magical Minority

Hugvísindasvið Magical Minority Social Class and Discrimination in the Harry Potter Novels Ritgerð til B.A.-prófs Anna Guðjónsdóttir Maí 2014 Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindasvið Enska Magical Minority Social Class and Discrimination in the Harry Potter Novels Ritgerð til B.A.-prófs Anna Guðjónsdóttir Kt.: 210190-2609 Leiðbeinandi: Anna Heiða Pálsdóttir Maí 2014 Abstract This essay explores the separation of people into different social classes in the Harry Potter novels and does as well give focus on the treatment of minority groups in the story. Dividing wizards and witches into upper, middle and lower class controls the wizard society and where the power lies. Those that form the upper class come from a long line of wizards and witches that are referred to as purebloods while those that form the lower class have parents who are Muggles, that is, possess no magical power. The essay explores the negative treatment of non-human beings and others that fall out of the norm in the wizard community and are placed as simple workers or even slaves since they are seen as inferior to wizards and witches. Authority and the upper class are portrayed in a very negative way since their sole interest seems to be on protecting their power and eliminating those that they deem unworthy of possessing magical power. The essay gives examples of characters that fall out of the norm and how they have accepted their place outside of the society. By applying Marxist theory focus is given on the class structure and shows how the upper class creates the superstructure while the lower class, formed by Muggleborn wizards and witches as well as the non-human beings, form the base of the society. -

WIZARD QUICK DRAW CHALLENGE Cut out the Words Below, Fold Them up and Put Them in a Hat Or Container

22 More Wizarding Activities YOU MAY PHOTOCOPY THIS SHEET WIZARD QUICK DRAW CHALLENGE Cut out the words below, fold them up and put them in a hat or container. Divide your guests into teams of two or more. Each turn, one member of the team selects a card and has to draw the item on a flipchart or large piece of paper, for the rest of their team to guess. Award 10 house points for each correct answer guessed. Nimbus Two Sorting Hat Thousand Cat Toad Broomstick Hogwarts Owl Wand Cauldron Express Flying Pumpkin Scar Portrait Motorbike Golden Ghost Rat Dragon Snitch Chocolate Diagon Butterbeer Frog Alley harrypotterbooknight.com #HarryPotterBookNight 25 More Wizarding Activities YOU MAY PHOTOCOPY THIS SHEET WIZARD WORDSEARCH Can you search out these characters from the Harry Potter books in the grid below? Words can read up, down, across, backwards and diagonally. S E V E R U S S N A P E H I F O A L E B E C L R A D R D L V U N E D H O R U E I E D O N D O A D R D D E U I E I A B G E Y L P F M S R M G B R L P E K R U M B E O Y I B O Y E H O I J L M R D M T H K T O N K S A U T U T N E V I L L E L C S D E C R O O K S H A N K S R M A L F O Y C R E P P H E D W I G I N N Y M N CROOKSHANKS HARRY POTTER REMUS DOBBY HERMIONE RON DUDLEY KRUM SEVERUS SNAPE DUMBLEDORE LUNA SIRIUS BLACK FRED MALFOY TOM RIDDLE GINNY NEVILLE TONKS HAGRID PEEVES VOLDEMORT HEDWIG PERCY harrypotterbooknight.com #HarryPotterBookNight 28 More Wizarding Activities YOU MAY PHOTOCOPY THIS SHEET WIZARDING WORD PLAY Anagrams and riddles play a big part in Harry and his friends’ adventures. -

Issues with Racism, Classism, and Ideology in Harry Potter Tiffany L

Northern Michigan University NMU Commons All NMU Master's Theses Student Works 5-2015 Not So Magical: Issues with Racism, Classism, and Ideology in Harry Potter Tiffany L. Walters [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.nmu.edu/theses Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Walters, Tiffany L., "Not So Magical: Issues with Racism, Classism, and Ideology in Harry Potter" (2015). All NMU Master's Theses. 42. https://commons.nmu.edu/theses/42 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at NMU Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in All NMU Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of NMU Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. NOT SO MAGICAL: ISSUES WITH RACISM, CLASSISM, AND IDEOLOGY IN HARRY POTTER By Tiffany Walters THESIS Submitted to Northern Michigan University In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Office of Graduate Education and Research May 2015 SIGNATURE APPROVAL FORM Not So Magical: Issues with Racism, Classism and Ideology in Harry Potter This thesis by Tiffany Walters is recommended for approval by the student’s thesis committee in the Department of English and by the Assistant Provost of Graduate Education and Research. Committee Chair: Dr. Kia Jane Richmond Date First Reader: Dr. Ruth Ann Watry Date Second Reader: N/A Date Department Head: Dr. Robert Whalen Date Dr. Brian D. Cherry Assistant Provost of Graduate Education and Research ABSTRACT NOT SO MAGICAL: ISSUES WITH RACISM, CLASSISM, AND IDEOLOGY IN HARRY POTTER By Tiffany Walters Although it is primarily a young adult fantasy series, the Harry Potter books are also focused on the battle against racial purification and the threat of a strictly homogenous magical society. -

An Exploration of JK Rowling's Social and Political Agenda in the Harry

Vollmer UW-L Journal of Undergraduate Research X (2007) Harry’s World: An Exploration of J.K. Rowling’s Social and Political Agenda in the Harry Potter Series Erin Vollmer Faculty Sponsor: Richard Gappa, Department of English ABSTRACT Over the years, the Harry Potter series by J.K. Rowling has grown in popularity, becoming one of the most read and most criticized pieces of children’s literature to date. Interestingly, the series has not only gained popularity with children, but also their adult counterparts. As a result of its adult success, Harry Potter has attracted more and more scholars to pursue serious literary analysis, most frequently exploring themes such as death and religion. However, the focus of this research is on the intertextual parallels of the numerous hierarchical structures found in the Harry Potter series, examining how these hierarchies develop the social and racial themes in the story and vice versa. A further purpose is to determine if there is a correlation between the power structures found in the series and our own, drawing on secondary criticisms and theory for support. Above all, although the series should not be reduced to “this versus that,” there is sufficient evidence to argue that a conflict of materialistic versus altruistic values is at work in the Harry Potter series. Therefore, the examination of race, hierarchy, and power assists in the recognition of the social and political systems at work in the series. Keywords: J.K. Rowling, Hierarchy, Materialism INTRODUCTION When a skinny boy with black hair, green eyes, and a telltale scar appeared on the scene in 1997, nobody could have predicted the significant impact this seemingly insignificant boy would have on the world. -

Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone the First in the Wonderful Best

Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone The first in the wonderful best-selling series of novels by writer J.K. Rowling comes ‘Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone’. The journey is just beginning for Harry Potter (Daniel Radcliffe); as an eleven year old orphan who lives in the cupboard under the stairs of his aunt’s house, Harry has not had the best of lives up until this point. He is under-appreciated and frankly unwanted. Harry’s life is about to change; soon he’ll find that his parents we’re not killed in a car crash as he thought, but that they were murdered by a horrifying dark wizard. He will soon attend a wizarding school and learn much that he never thought possible; he will learn how to fly as well as play the sport of Quidditch. Harry’s life will never be the same again! Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets Harry Potter is a well-known name when it comes to the world of Wizardry, and he’s got a big reputation to live up to. His reputation, as well as his magical abilities, are about to be put to the test! A mysterious visitor named Dobby the House Elf appears at Harry’s house over the summer and warns Harry not to return to Hogwarts. Knowing his life will be in danger, Harry is determined that this warning holds no merit and returns to Hogwarts, but soon finds that perhaps he shouldn’t have. “The Chamber of Secrets Has Been Opened. -

A Fiction-Based Religion Within the Harry Potter Fandom

Religions 2014, 5, 219–267; doi:10.3390/rel5010219 OPEN ACCESS religions ISSN 2077-1444 www.mdpi.com/journal/religions Article ‘Snapewives’ and ‘Snapeism’: A Fiction-Based Religion within the Harry Potter Fandom Zoe Alderton Independent scholar; E-Mail: [email protected] Received: 18 December 2013; in revised form: 6 February 2014 / Accepted: 11 February 2014 / Published: 3 March 2014 Abstract: The book and film franchise of Harry Potter has inspired a monumental fandom community with a veracious output of fanfiction and general musings on the text and the vivid universe contained therein. A significant portion of these texts deal with Professor Severus Snape, the stern Potions Master with ambiguous ethics and loyalties. This paper explores a small community of Snape fans who have gone beyond a narrative retelling of the character as constrained by the work of Joanne Katherine Rowling. The ‘Snapewives’ or ‘Snapists’ are women who channel Snape, are engaged in romantic relationships with him, and see him as a vital guide for their daily lives. In this context, Snape is viewed as more than a mere fictional creation. He is seen as a being that extends beyond the Harry Potter texts with Rowling perceived as a flawed interpreter of his supra-textual essence. While a Snape religion may be seen as the extreme end of the Harry Potter fandom, I argue that religions of this nature are not uncommon, unreasonable, or unprecedented. Popular films are a mechanism for communal bonding, individual identity building, and often contain their own metaphysical discourses. Here, I plan to outline the manner in which these elements resolve within extreme Snape fandom so as to propose a nuanced model for the analysis of fandom-inspired religion without the use of unwarranted veracity claims.