Translating Burns

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Discography of Robert Burns 1948 to 2002 Thomas Keith

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 33 | Issue 1 Article 30 2004 A Discography of Robert Burns 1948 to 2002 Thomas Keith Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Keith, Thomas (2004) "A Discography of Robert Burns 1948 to 2002," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 33: Iss. 1. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol33/iss1/30 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thomas Keith A Discography of Robert Bums 1948 to 2002 After Sir Walter Scott published his edition of border ballads he came to be chastised by the mother of James Hogg, one Margaret Laidlaw, who told him: "There was never ane 0 my sangs prentit till ye prentit them yoursel, and ye hae spoilt them awthegither. They were made for singing an no forreadin: butye hae broken the charm noo, and they'll never be sung mair.'l Mrs. Laidlaw was perhaps unaware that others had been printing Scottish songs from the oral tradition in great numbers for at least the previous hundred years in volumes such as Allan Ramsay's The Tea-Table Miscellany (1723-37), Orpheus Caledonius (1733) compiled by William Thompson, James Oswald's The Cale donian Pocket Companion (1743, 1759), Ancient and Modern Scottish Songs (1767, 1770) edited by David Herd, James Johnson's Scots Musical Museum (1787-1803) and A Select Collection of Original Scotish Airs (1793-1818) compiled by George Thompson-substantial contributions having been made to the latter two collections by Robert Burns. -

Thomas Pennant's Tours of Wales and Scotland University of Glasgow, 1

Thomas Pennant’s Tours of Wales and Scotland University of Glasgow, 1-2 February 2013 The first of Two multi-disciplinary workshops hosted by the University of Wales Centre for Advanced Welsh and Celtic Studies and the University of Glasgow. Sponsored by the British Academy and supported by the Learned Society of Wales Friday 1st February Registration with tea and coffee: 3.00–4.00pm, Room 202, 4 University Gardens 4.00-4.45pm: Nigel Leask (University of Glasgow), ‘Robert Riddell’s Annotated and Graingerized Copy of Pennant’s Scottish Tours’, Henry Heaney Room, Special Collections, Glasgow University Library 5.00pm: Plenary Lecture R. Paul Evans (Denbigh High School), ‘Thomas Pennant's Tours of Scotland: "A round jump from ornithology to antiquity" Drinks and Dinner Saturday, 2nd February 9.30-11.00am. Domhmnall Uilleam Stiubhart (University of Edinburgh), ‘Highland Sources for Pennant, and ‘indigenous’ travel literature in the 18th century’ Thomas Clancy (University of Glasgow), ‘Pennant, Saint’s Cults, and Scottish Place Names’ 11.00-11.30. Tea & Coffee 11.30am-1.00pm. Mary-Ann Constantine (University of Wales), ‘Pennant’s Heart of Darkness’ Helen McCormack (University of Glasgow), ‘Pennant, Hunter, Stubbs and the Pursuit of Nature’ 1.00-2.00pm Sandwich lunch 2.00-3.30pm Mike Basset (National Museum of Wales), Pennant and geology (title TBC) Alison Ksiazkekiewicz (University of Cambridge), ‘Sir Joseph Banks, Thomas Pennant and the Isle of Staffa as 'natural' architecture’ 3.30-4pm Tea & Coffee 4.00-4.40pm. Tom Furniss (University of Strathclyde), ‘Geological Observation in Pennant’s ‘Tours of Scotland’ 4.40-5.30pm. -

The Construction of the Scottish Military Identity

RUINOUS PRIDE: THE CONSTRUCTION OF THE SCOTTISH MILITARY IDENTITY, 1745-1918 Calum Lister Matheson, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2011 APPROVED: Geoffrey Wawro, Major Professor Guy Chet, Committee Member Michael Leggiere, Committee Member Richard McCaslin, Chair of the Department of History James D. Meernik, Acting Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Matheson, Calum Lister. Ruinous pride: The construction of the Scottish military identity, 1745-1918. Master of Arts (History), August 2011, 120 pp., bibliography, 138 titles. Following the failed Jacobite Rebellion of 1745-46 many Highlanders fought for the British Army in the Seven Years War and American Revolutionary War. Although these soldiers were primarily motivated by economic considerations, their experiences were romanticized after Waterloo and helped to create a new, unified Scottish martial identity. This militaristic narrative, reinforced throughout the nineteenth century, explains why Scots fought and died in disproportionately large numbers during the First World War. Copyright 2011 by Calum Lister Matheson ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER I: THE HIGHLAND WARRIOR MYTH ........................................................... 1 CHAPTER II: EIGHTEENTH CENTURY: THE BUTCHER‘S BILL ................................ 10 CHAPTER III: NINETEENTH CENTURY: THE THIN RED STREAK ............................ 44 CHAPTER IV: FIRST WORLD WAR: CULLODEN ON THE SOMME .......................... 68 CHAPTER V: THE GREAT WAR AND SCOTTISH MEMORY ................................... 102 BIBLIOGRAPHY ......................................................................................................... 112 iii CHAPTER I THE HIGHLAND WARRIOR MYTH Looking back over nearly a century, it is tempting to see the First World War as Britain‘s Armageddon. The tranquil peace of the Edwardian age was shattered as armies all over Europe marched into years of hellish destruction. -

Melodic Identity and Tune Resemblance Karen E. Mcaulay

1 ABSTRACTS (grouped by session) Session 1: Melodic Identity and Tune Resemblance Karen E. McAulay (Royal Conservatoire of Scotland, Glasgow) ‘All the right notes, but not necessarily in the right order’*: Musical Resemblances over the Border The appealing Northumbrian pipe-tune, “I saw my love come passing by me”, appears in at least three nineteenth century sources, and again in Cock’s Tutor for the Northumbrian Half-Long Bagpipes. The latest two of these are shorter, whilst the first two elaborate the tune with variations. Nonetheless, the resemblances are clear; their kinship is indisputable. However, there are two much earlier appearances of similar tunes in publications north of the border. A century older, each has a different title, and although the shapes of these tunes are undeniably similar, they are certainly neither identical forerunners to one another, nor to “I saw my love”. Indeed, one source was linked in 1925 to a totally different tune. Notwithstanding this earlier identification, I dispute the similarity, and propose that there is some kind of link between “I saw my love” and her earlier Scottish cousins. Whilst the Tune Archive enabled me to trace the iterations of the Border tunes, it failed to flag up these Scottish tunes as potential relatives, partly because their rhythmic notation means the Theme Code index failed to pick up the same strong beats. I propose to demonstrate the methodology I have adopted to attempt to prove my hypothesis. If I’m right, it suggests that before I saw my love come passing by me, she had enjoyed a bit of a shadowy Celtic past. -

CARMEN DAAH Mezzo-Soprano with J. Hunter Macmillan, Piano Recorded London, January 1925 MC-6847 Kishmul's Galley (“Songs Of

1 CARMEN DAAH Mezzo-soprano with J. Hunter MacMillan, piano Recorded London, January 1925 MC-6847 Kishmul’s galley (“songs of the Hebrides”) (trad. arr. Marjorie Kennedy Fraser) Bel 705 MC-6848 The spinning wheel (Dunkler) Bel 705 MC-6849 Coming through the rye (Robert Burns; Robert Brenner) Bel 706 MC-6850 O rowan tree – ancient Scots song (trad. arr. J. H. MacMillan) Bel 707 MC-6851 Jock o’ Hazeldean (Walter Scott; trad. arr. J. Hunter MacMillan Bel 706 MC-6853 The herding song (trad. arr. Mrs. Kennedy Fraser) Bel 707 THE DAGENHAM GIRL PIPERS (formed 1930) Led by Pipe-Major Douglas Taylor. 12 pipers, 4 drummers Recorded Chelsea Town Hall, King’s Road, London, Saturday, 19th. November 1932 GB-5208-1/2 Lord Lovat’s lament; Bruce’s address – lament (both trad) Panachord 25365; Rex 9584 GB-5209-1/2 Earl of Mansfield – march (John McEwan); Lord Lovat’s – strathspey (trad); Mrs McLeod Of Raasay – reel (Alexander MacDonald) Panachord 25365; Rex 9584 GB-5210-1 Highland Laddie – march (trad); Lady Madelina Sinclair – strathspey (Niel Gow); Tail toddle reel (trad) Panachord 25370; Rex 9585 GB-5211-3 An old Highland air (trad) Panachord 25370; Rex 9585 Pipe Major Peggy Isis (solos); 15 pipers; 4 side drums; 1 bass drum. Recorded Studio No. 2, 3 Abbey Road, London, Tuesday, 26th. March 1957 Military marches – intro. Scotland the brave; Mairi’s wedding; Athole Highlanders (all trad) Par GEP-8634(EP); CapUS T-10125(LP) Pipes in harmony – intro. Maiden of Morven (trad); Green hills of Tyrol (Gioacchino Rossini. arr. P/M John MacLeod) Par GEP-8634(EP); CapUS T-10125(LP) Corn rigs – march (trad); Monymusk – strathspey (Daniel Dow); Reel o’ Tulloch (John MacGregor); Highland laddie (trad) Par GEP-8634(EP); CapUS T-10125(LP) Quick marches – intro. -

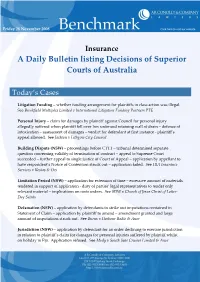

A Daily Bulletin Listing Decisions of Superior Courts of Australia

Friday 28 November 2008 Click here to visit our website Insurance A Daily Bulletin listing Decisions of Superior Courts of Australia Today’s Cases Litigation Funding – whether funding arrangement for plaintiffs in class action was illegal. See Brookfield Multiplex Limited v International Litigation Funding Partners PTE Personal Injury – claim for damages by plaintiff against Council for personal injury allegedly suffered when plaintiff fell over low unfenced retaining wall of drain – defence of intoxication – assessment of damages – verdict for defendant at first instance - plaintiff’s appeal allowed. See Jackson v Lithgow City Council Building Dispute (NSW) – proceedings before CTTT – tribunal determined separate question concerning validity of termination of contract – appeal to Supreme Court succeeded – further appeal to single justice of Court of Appeal – application by appellant to have respondent’s Notice of Contention struck out – application failed. See HIA Insurance Services v Kostas & Ors Limitation Period (NSW) – application for extension of time – excessive amount of materials tendered in support of application - duty of parties’ legal representatives to tender only relevant material – implications on costs orders. See SDW v Church of Jesus Christ of Latter- Day Saints Defamation (NSW) – application by defendants to strike out imputations contained in Statement of Claim – application by plaintiff to amend – amendment granted and large amount of imputations struck out. See Burns v Harbour Radio & Anor Jurisdiction (NSW) – application by defendant for an order declining to exercise jurisdiction in relation to plaintiff’s claim for damages for personal injuries suffered by plaintiff whilst on holiday in Fiji. Application refused. See Mody v South Seas Cruises Limited & Anor Motor Accident (NSW) – sections 108 & 109: Motor Accidents Compensation Act 1999 – whether “full and satisfactory” explanation – leave to commence proceedings granted. -

The Songs of Robert Burns

— ; ; — I. LOVE-SONGS : PERSONAL 387 ' O saw ye my father, or saw ye my mother, Or saw ye my true love, John? I saw not your father, I saw not your mother, But I saw your true love, John. ' Up Johnnie rose, and to the door he goes, And gently tirled the pin ; The lassie taking tent, unto the door she went, And she open'd and let him in. * Flee, flee up, my bonny grey cock. And craw whan it is day Your neck shall be like the bonny beaten gold, And your wings of the silver grey. ' The cock prov'd false, and untrue he was. For he crew an hour o'er soon The lassie thought it day when she sent her love away, And it was but a blink of the moon.' The origin of this beautiful song has been disputed by Chappell {Popular Music, p. 7J/), who claimed that the original publication of five stanzas is in Vocal Music, or the Songsters Companion, London, 1772, ii. j6. He stated that a Scottified version was reprinted by Herd in 1776, but I have shown that the song was printed in Herd's first edition of 1769. The third stanza in Focal Music, as follows, can be compared with the above second stanza : ' Then John he up arose, and to the door he goes, And he twirled, he twirled at the pin ; The lassie took the hint, and to the door she went, And she let her true love in.' The English copyist discloses his ignorance of the Scots language in the second line, where the lover tirls the wooden latch or pin of the door to arrest his sweetheart's attention. -

21St Century Global Anchor Institutions: Universities, Cities and the International Talent Economy”

Universitas 21 Annual Network Meeting and Presidential Symposium 2017 University of Nottingham “21st Century Global Anchor Institutions: universities, cities and the international talent economy” Symposium Overview Higher education has, for centuries, been at the vanguard of globalism – with academics and students swapping ideas and spreading innovation long before the current system of economic globalisation emerged. From the ‘wandering scholars’ of ancient India, via the development of the first formal European University in Bologna in the 11th Century, to the explosion of modern global higher education – universities are, by their very nature, institutions that enrich the human capital of nations. Today, “Human Capital” is a theory at the height of its prominence in the thoughts and actions of global economists, businesses and policymakers. There is broad international consensus that long-term economic prosperity lies in a race-to-the-top, and that nations should pursue policies that drive greater education, encourage innovation and retain talent. In most OECD countries economic growth is now driven to a higher degree by intangible assets than by traditional capital such as machinery or equipment. Knowledge, data, patents and human capital are the new sources of growth. And innovation in these intellectual assets will spur growth to take off again. The quantity and quality of intellectual innovation will not only determine when and how countries will find the way out of the recession, but also the post- recession new global economic order. Universities across the Universitas 21 Group and beyond have a long and established track- record of driving economic growth and socio-cultural prosperity in their host cities and regions. -

Conference Outline

ROBERT BURNS 1759 TO 2009 15 – 17 January 2009 Centre for Robert Burns Studies Director, Dr Gerard Carruthers Associate Director, Dr Kirsteen McCue www.glasgow.ac.uk/robertburnsstudies ROBERT BURNS 1759 TO 2009 CONFERENCE OUTLINE THURSDAY 15 JANUARY 08.30 – 09.30 Registration Hunter Hall West (It will be possible to register throughout the day.) 09.45 –10.00 Official Conference Launch: Kelvin Gallery Sir Muir Russell KCB FRSE, Principal and Vice Chancellor of the University of Glasgow introduces Fiona Hyslop MSP, Cabinet Secretary for Education and Lifelong Learning Opening Plenary: 10.00 – 11.00 Dr Leith Davis, Simon Fraser University, Canada, Transatlantic Burns, Kelvin Gallery Chair: Gerry Carruthers, Centre for Robert Burns Studies, Department of Scottish Literature, University of Glasgow 11.00 – 11.30 Tea and coffee break, refreshments in Hunter Hall West 11.30 – 12.30 Panels 1 12.30 - 14.00 Lunch 14.00 – 15.00 Panels 2 15.00 – 15.30 Tea and coffee break, refreshments in Hunter Hall West Plenary Two: 15.30 – 16.30 Prof Jon Mee, University of Warwick, England Kelvin Gallery Why the English had to invent Robert Burns Chair: Nigel Leask, Department of English Literature, University of Glasgow 16.30 – 17.00 break Plenary Three: 17.00 – 18.00 Prof G Ross Roy, University of Columbia, South Carolina Kelvin Gallery Chair: RDS Jack, University of Edinburgh Fifty Years of Robert Burns and Burns Collecting, G Ross Roy in interview with Patrick Scott Oxford University Press Edition of the 18.00 - 19.00 COLLECTED WORKS OF ROBERT BURNS Kelvin -

James Currie's Editing of the Correspondence of Robert Burns Robert D

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 35 | Issue 1 Article 30 2007 James Currie's Editing of the Correspondence of Robert Burns Robert D. Thornton State University of New York, New Paltz Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Thornton, Robert D. (2007) "James Currie's Editing of the Correspondence of Robert Burns," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 35: Iss. 1, 403–418. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol35/iss1/30 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Robert D. Thornton J ames Currie's Editing of the Correspondence of Robert Bums The best known letter of Burns edited by James Currie in Volume One is the autobiography addressed to Dr. John Moore.! Unlike almost every other person suggested for the task of editing, Currie could have had the posted letter itself. Apparently he never accepted Moore's offer of it. Not interested in collating and without the time and the space even if he were, Currie had in Liverpool what he needed to go on confidently. "There are" he tells his read ers: Various copies of this letter, in the author's- hand-writing; and one of these, evi dently corrected, is in the book in which he copied several of his letters. This has been used for the present, with some omissions, and one slight alterations suggested by Gilbert Burns.2 lThe Letters of Robert Burns, 2nd edn., ed. -

Discography Section 18: R (PDF)

1 FRAB THE RHYMER ( ? – 1944). (r.n. Dr. Douglas S. Raitt) Scottish humorous speech with piano Recorded West Hampstead, London, prob. June/July 1939 (before 13th. July) M-873 The 'Breembraes' A.R.P. (D. S. Raitt) Bel 2408, BL-2408 M-874 The fairmer's ball (D. S. Raitt) Bel 2407, BL-2407 M-875 Kirsty (D. S. Raitt) Bel 2405, BL-2405 M-876 The Kilt Society's ball (D. S. Raitt) Bel 2407, BL-2407 M-877 As the auld cock craws (D. S. Raitt) Bel 2406, BL-2406 M-878 Pullin' the strings (D. S. Raitt) Bel 2406, BL-2406 M-879 A wee stoot laddie (D. S. Raitt) Bel 2405, BL-2405 M-880 Ye widna ken 'Breembraes' (D. S. Raitt) Bel 2408, BL-2408 NOTE: The artist received ¾d. per side royalties. Whilst a student at Aberdeen University in 1927 he had written and produced the annual students’ union show, “Northern Lights”. JACK RADCLIFFE (Cumnock, 1900 – 1967). Vocal Recorded Montreal, ca early 1954 Katie McGraw ( - ) Thistle T-221 Best wee lassie ( - ) Thistle T-221 NOTE: This artist was Scots and probably on tour with Robert Wilson & Company ROBERT RADFORD (Nottingham, 1875 – London, 1933). Bass with the Band of The Coldstream Guards Recorded London, Wednesday, 6th. November 1917 Scots wha hae (Robert Burns; trad) HMV 02761(s/s)(12”); HMV D-104 NOTE: Other records by this artist are of no Scots interest. CHARLES RAE Violin solo Recorded Megginch Castle, Errol, Perth, between April – November 1934 A-283 White heather selections ( - ) Great Scott A-283 NINA RAE (Georgiana Rae) (Glasgow, 1879 - ? ). -

Book Index by Publisher

MacLean Collection Section B - Book Index by Publisher MacLean Publisher Title of book Date of Publication Collection # Bagpipe Music (Parts of Several Books) 93 Clarkson's Musical Entertainment 1820 20 Dan R. MacDonald - A Collection of Highland 51 Music Dan R. MacDonald Compositions 1993 49 Dan R. MacDonald's Collection of Scottish Music 101 Edinburgh Collection Part IV, The 96 John D. Bowie's Collection of Strathspey Reels & 1789 14 Country Dances Middleton's Cabinet of Dance Music For The Violin 102 NS Collection of Airs 1794 2 R. J. MacDonald's Collection of Original Scots 1962 47 C Tunes, Strathspeys, Jigs and Dances for Violin Bk 3 R. J. MacDonald's Collection of Reels & Slow Airs 1952 47 A For Violin, Book 1 R. J. MacDonald's Collection of Reels & Strathspeys as collected from the MacIntosh, Morrison and Lowe 1958 47 B Collections. Second Book Robert Ross's Choice Selection of Scots, 1780 7 A Reels,Country Dances & Strathspeys William Shepherd's Collection Vol I 10 Allan, Mozart Allan's Collection of Reels & Strathspeys 98 Allan, Mozart Allan's Irish Fiddler 91 Baley & Ferguson The Scottish Violinist 90 Bayley & Ferguson Alfred Moffat Collection - 202 Gems of Irish Melody 79 Bayley & Ferguson Alfred Moffatt's Dance Music of the North 1908 83 Auld Scotch Sangs Fantasia on Scottish Airs for Bayley & Ferguson 99 Violin & Piano Bayley & Ferguson Balmoral Reel Book, The 85 Cairngorm Collection of Strathspeys, Reels, Bayley & Ferguson 1922 36 Hornpipes, Pastorals, Marches, Jigs Etc., The Bayley & Ferguson Flowers of Scottish Melody 1935 37 Bayley & Ferguson Harp and Claymore, The 1904 33 Bayley & Ferguson J.