Expeditionary Forces: Superior Technology Defeated—The Battle of Maiwand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stamps of India Army Postal Covers (APO)

E-Book - 22. Checklist - Stamps of India Army Postal Covers (A.P.O) By Prem Pues Kumar [email protected] 9029057890 For HOBBY PROMOTION E-BOOKS SERIES - 22. FREE DISTRIBUTION ONLY DO NOT ALTER ANY DATA ISBN - 1st Edition Year - 8th May 2020 [email protected] Prem Pues Kumar 9029057890 Page 1 of 27 Nos. Date/Year Details of Issue 1 2 1971 - 1980 1 01/12/1954 International Control Commission - Indo-China 2 15/01/1962 United Nations Force - Congo 3 15/01/1965 United Nations Emergency Force - Gaza 4 15/01/1965 International Control Commission - Indo-China 5 02/10/1968 International Control Commission - Indo-China 6 15.01.1971 Army Day 7 01.04.1971 Air Force Day 8 01.04.1971 Army Educational Corps 9 04.12.1972 Navy Day 10 15.10.1973 The Corps of Electrical and Mechanical Engineers 11 15.10.1973 Zojila Day, 7th Light Cavalary 12 08.12.1973 Army Service Corps 13 28.01.1974 Institution of Military Engineers, Corps of Engineers Day 14 16.05.1974 Directorate General Armed Forces Medical Services 15 15.01.1975 Armed Forces School of Nursing 03.11.1976 Winners of PVC-1 : Maj. Somnath Sharma, PVC (1923-1947), 4th Bn. The Kumaon 16 Regiment 17 18.07.1977 Winners of PVC-2: CHM Piru Singh, PVC (1916 - 1948), 6th Bn, The Rajputana Rifles. 18 20.10.1977 Battle Honours of The Madras Sappers Head Quarters Madras Engineer Group & Centre 19 21.11.1977 The Parachute Regiment 20 06.02.1978 Winners of PVC-3: Nk. -

The Causes of the Second Anglo-Afghan War, a Probe Into the Reality of the International Relations in Central Asia in the Second Half of the 19Th Century1

wbhr 01|2014 The Causes of the Second Anglo-Afghan War, a Probe into the Reality of the International Relations in Central Asia in the Second Half of the 19th Century1 JIŘÍ KÁRNÍK Institute of World History, Faculty of Arts, Charles University, Prague Nám. J. Palacha 2, 116 38 Praha, Czech Republic [email protected] Central Asia has always been a very important region. Already in the time of Alexander the Great the most important trade routes between Europe and Asia run through this region. This importance kept strengthening with the development of the trade which was particularly connected with the famous Silk Road. Cities through which this trade artery runs through were experiencing a real boom in the late Middle Ages and in the Early modern period. Over the wealth of the business oases of Khiva and Bukhara rose Samarkand, the capital city of the empire of the last Great Mongol conqueror Timur Lenk (Tamerlane).2 The golden age of the Silk Road did not last forever. The overseas discoveries and the rapid development of the transoceanic sailing was gradually weakening the influence of this ancient trade route and thus lessening the importance and wealth of the cities and areas it run through. The profits of the East India companies were so huge that it paid off for them to protect their business territories. In the name of the trade protection began also the political penetration of the European powers into the overseas areas and empires began to emerge. 1 This article was created under project British-Afghan relations in 19th century which is dealt with in 2014 at Faculty of Arts of Charles University in Prague with funds from Charles University Grant Agency. -

The First Six Months GR&D

Governance, Reconstruction, Jan 15, GR&D & Development 2010 Interim Report: The First Six Months GR&D Governance, Reconstruction, & Development “What then should the objective be for this war? The aim needs to be to build an administrative and judicial infrastructure that will deliver security and stability to the population and, as a result, marginalize the Taliban. Simultaneously, it can create the foundations for a modern nation.” -Professor Akbar S. Ahmed Ibn Khaldun Chair of Islamic Studies American University Cover Captions (clockwise): Afghan children watch US Soldiers from 2nd Battalion, 1st Infantry Regiment, 5th Brigade, 2nd Infantry Di- vision conduct a dismounted patrol through the village of Pir Zadeh, Dec. 3, 2009. (US Air Force photo by Staff Sgt. Dayton Mitchell) US Soldiers from 4th Battalion, 23rd Infantry Regiment, 5th Brigade, 2nd Infantry Division conduct a joint patrol with Afghan National Army soldiers and Afghan National Policemen in Shabila Kalan Village, Zabul Prov- ince, Nov. 30, 2009. (US Air Force photo by Tech. Sgt. Efren Lopez) An Afghan elder speaks during a shura at the Arghandab Joint District Community Center, Dec. 03, 2009. (US Air Force photo by Tech. Sgt. Francisco V. Govea II) An Afghan girl awaits to receive clothing from US Soldiers from 4th Battalion, 23rd Infantry Regiment, Boragay Village, Zabul Province, Afghanistan, Dec. 4, 2009. US Soldiers are conducting a humanitarian relief project , "Bundle-up,” providing Afghan children with shoes, jackets, blankets, scarves, and caps. (US Air Force -

Classic Arms (Pty) Ltd Is Proud to Present Its 56Th Auction of Collectable, Classic, Sporting & Other Arms, Accoutrements and Edged Weapons

Classic Arms (Pty) Ltd Is proud to present its 56th Auction Of Collectable, Classic, Sporting & Other Arms, Accoutrements and Edged Weapons. The Portuguese Club, Nita Street, Del Judor X4, Witbank on 1st April 2017 Viewing will start at 09:00 and Auction at 12:00 Enquiries: Tel: 013 656 2923 Fax: 013 656 1835 Email: [email protected] CATEGORY A ~ COLLECTABLES Lot # Lot Description Estimate A1 Deactivated Tokarev M1938 [SVT] Semi-Auto Rifle R 4500.00 One of the first successful semi-auto rifles to see military service. Russian manufactured 1941. Very good condition. A2 7,62mm FN Heavy Barrel Deact R 6950.00 Ex Rhodesian war example complete with Rhodesian camo paint. Bipod and carrying handle removed. New SA spec deact with moving parts. A3 .177 Air Rifle-Unidentified Early Model R 200.00 Fair condition. A4 .177 Webley Mk11 Service Air Rifle R 4500.00 Bolt action type air rifle which would originally have had both .177 and .22 calibre barrels. Detachable barrel of 25,5", ramp foresight, adjustable rear sight and tang peep sight. Air receiver marked "Webley Service Air Rifle Mark 11" Stock in good plus condition, some loss to finish of metalwork, cocking lever not engaging and would require attention. A5 .177 Webley Mk3 "Super Target" Air Rifle R 3950.00 Introduced 1963, production is assumed to have terminated in 1975. Fitted with Parker-Hale PH17B target peep sight and tunnel foresight FS22A. No rear sight blade at all. Spare foresight blades in screw top canister fitted to underside of pistol grip. "Supertarget" to air chamber. -

Vol 66 No 3: September 2014

www.gurkhabde.com/publication The magazine for Gurkha Soldiers and their Families PARBVolAT 66 No 3: SeptemberE 2014 Gurkha permanent staff with the World Marathon Champion Mr Kiprotich during the Bupa Great North Run 2014 ii PARBATE Vol 66 No 3 September 2014 PARBATE ENTERING A MODERN ERA HQ Bde of Gurkhas, FASC, Sandhurst, Camberley, Surrey, GU15 4PQ. All enquiries Tel: 01276412614 / 94261 2614 Fax: 0127641 2694 / 94261 2694 Email: [email protected] Editor Cpl Sagar Sherchan 0127641 2614 [email protected] Comms Officer Cpl Sagar Sherchan GSPS Mr Ken Pike 0127641 2776 [email protected] elcomeelcome to to a a brand brand new new edition edition with with lots lots of of changes changes Please send your articles together with high WWinin terms terms of of the the outline outline and and design. design. Lots Lots of of attractive attractive quality photographs (min 300dpi), through your unit’s Parbate Rep, to: subjectssubjects and and some some great great photographs photographs from from around around the the globe globe The Editor, Parbate Office, awaitawait our our readers. readers. HQBG, FASC, Camberley, Surrey, GU15 4PQ AsA soperations operations in in Afghanistan Afghanistan gradually gradually wind wind down, down, Parbate is published every month by kind permission soldierssoldiers from from 1 1 RGR RGR settled settled in in Brunei Brunei focusing focusing on on getting getting of HQBG. It is not an official publication and the views expressed, unless specifically stated otherwise, do backback the the basics basics right right (page (page 2). 2). not reflect MOD or Army policy and are the personal views of the author. -

Kandahar Survey Report

Agency for Rehabilitation & Energy-conservation in Afghanistan I AREA Kandahar Survey Report February 1996 AREA Office 17 - E Abdara Road UfTow Peshawar, Pakistan Agency for Rehabilitation & Energy-conservation in Afghanistan I AREA Kandahar Survey Report Prepared by Eng. Yama and Eng. S. Lutfullah Sayed ·• _ ....... "' Content - Introduction ................................. 1 General information on Kandahar: - Summery ........................... 2 - History ........................... 3 - Political situation ............... 5 - Economic .......................... 5 - Population ........................ 6 · - Shelter ..................................... 7 -Cost of labor and construction material ..... 13 -Construction of school buildings ............ 14 -Construction of clinic buildings ............ 20 - Miscellaneous: - SWABAC ............................ 2 4 -Cost of food stuff ................. 24 - House rent· ........................ 2 5 - Travel to Kanadahar ............... 25 Technical recommendation .~ ................. ; .. 26 Introduction: Agency for Rehabilitation & Energy-conservation in Afghanistan/ AREA intends to undertake some rehabilitation activities in the Kandahar province. In order to properly formulate the project proposals which AREA intends to submit to EC for funding consideration, a general survey of the province has been conducted at the end of Feb. 1996. In line with this objective, two senior staff members of AREA traveled to Kandahar and collect the required information on various aspects of the province. -

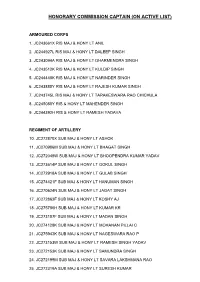

Honorary Commission Captain (On Active List)

HONORARY COMMISSION CAPTAIN (ON ACTIVE LIST) ARMOURED CORPS 1. JC243661X RIS MAJ & HONY LT ANIL 2. JC244927L RIS MAJ & HONY LT DALEEP SINGH 3. JC243094A RIS MAJ & HONY LT DHARMENDRA SINGH 4. JC243512K RIS MAJ & HONY LT KULDIP SINGH 5. JC244448K RIS MAJ & HONY LT NARINDER SINGH 6. JC243880Y RIS MAJ & HONY LT RAJESH KUMAR SINGH 7. JC243745L RIS MAJ & HONY LT TARAKESWARA RAO CHICHULA 8. JC245080Y RIS & HONY LT MAHENDER SINGH 9. JC244392H RIS & HONY LT RAMESH YADAVA REGIMENT OF ARTILLERY 10. JC272870X SUB MAJ & HONY LT ASHOK 11. JC270906M SUB MAJ & HONY LT BHAGAT SINGH 12. JC272049W SUB MAJ & HONY LT BHOOPENDRA KUMAR YADAV 13. JC273614P SUB MAJ & HONY LT GOKUL SINGH 14. JC272918A SUB MAJ & HONY LT GULAB SINGH 15. JC274421F SUB MAJ & HONY LT HANUMAN SINGH 16. JC270624N SUB MAJ & HONY LT JAGAT SINGH 17. JC272863F SUB MAJ & HONY LT KOSHY AJ 18. JC275786H SUB MAJ & HONY LT KUMAR KR 19. JC273107F SUB MAJ & HONY LT MADAN SINGH 20. JC274128K SUB MAJ & HONY LT MOHANAN PILLAI C 21. JC275943K SUB MAJ & HONY LT NAGESWARA RAO P 22. JC273153W SUB MAJ & HONY LT RAMESH SINGH YADAV 23. JC272153K SUB MAJ & HONY LT SAMUNDRA SINGH 24. JC272199M SUB MAJ & HONY LT SAVARA LAKSHMANA RAO 25. JC272319A SUB MAJ & HONY LT SURESH KUMAR 26. JC273919P SUB MAJ & HONY LT VIRENDER SINGH 27. JC271942K SUB MAJ & HONY LT VIRENDER SINGH 28. JC279081N SUB & HONY LT DHARMENDRA SINGH RATHORE 29. JC277689K SUB & HONY LT KAMBALA SREENIVASULU 30. JC277386P SUB & HONY LT PURUSHOTTAM PANDEY 31. JC279539M SUB & HONY LT RAMESH KUMAR SUBUDHI 32. -

Child Friendly School Baseline Survey

BASELINE SURVEY OF CHILD-FRIENDLY SCHOOLS IN TEN PROVINCES OF AFGHANISTAN REPORT submitted to UNICEF Afghanistan 8 March 2014 Society for Sustainable Development of Afghanistan House No. 2, Street No. 1, Karti Mamorin, Kabul, Afghanistan +93 9470008400 [email protected] CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 1 1.1 BACKGROUND ........................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 STUDY MODIFICATIONS ......................................................................................................... 2 1.3 STUDY DETAILS ...................................................................................................................... 4 1.4 REPORT STRUCTURE ............................................................................................................... 6 2. APPROACH AND METHODOLOGY ........................................................................ 7 2.1 APPROACH .......................................................................................................................... 7 2.2 METHODOLOGY ................................................................................................................ 8 3. TRAINING OF FIELD STAFF ..................................................................................... 14 3.1 OVERVIEW ........................................................................................................................ -

A Political Biography of King Amanullah Khan

A POLITICAL BIOGRAPHY OF KING AMANULLAH KHAN DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF iJlajSttr of ^Ijiloioplip IN 3 *Kr HISTORY • I. BY MD. WASEEM RAJA UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF DR. R. K. TRIVEDI READER CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDU) 1996 J :^ ... \ . fiCC i^'-'-. DS3004 CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY r.u Ko„ „ S External ; 40 0 146 I Internal : 3 4 1 DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSTTY M.IGARH—202 002 fU.P.). INDIA 15 October, 1996 This is to certify that the dissertation on "A Political Biography of King Amanullah Khan", submitted by Mr. Waseem Raja is the original work of the candidate and is suitable for submission for the award of M.Phil, degree. 1 /• <^:. C^\ VVv K' DR. Rij KUMAR TRIVEDI Supervisor. DEDICATED TO MY DEAREST MOTHER CONTENTS CHAPTERS PAGE NO. Acknowledgement i - iii Introduction iv - viii I THE LAND AND THE PEOPLE 1-11 II HISTORICAL ANTECEDANTS 12 - 27 III AMANULLAH : EARLY DAYS AND FACTORS INFLUENCING HIS PERSONALITY 28-43 IV AMIR AMANULLAH'S ASSUMING OF POWER AND THE THIRD ANGLO-AFGHAN WAR 44-56 V AMIR AMANULLAH'S REFORM MOVEMENT : EVOLUTION AND CAUSES OF ITS FAILURES 57-76 VI THE KHOST REBELLION OF MARCH 1924 77 - 85 VII AMANULLAH'S GRAND TOUR 86 - 98 VIII THE LAST DAYS : REBELLION AND OUSTER OF AMANULLAH 99 - 118 IX GEOPOLITICS AND DIPLCMIATIC TIES OF AFGHANISTAN WITH THE GREAT BRITAIN, RUSSIA AND GERMANY A) Russio-Afghan Relations during Amanullah's Reign 119 - 129 B) Anglo-Afghan Relations during Amir Amanullah's Reign 130 - 143 C) Response to German interest in Afghanistan 144 - 151 AN ASSESSMENT 152 - 154 BIBLIOGRAPHY 155 - 174 APPENDICES 175 - 185 **** ** ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The successful completion of a work like this it is often difficult to ignore the valuable suggestions, advice and worthy guidance of teachers and scholars. -

Nation Building Process in Afghanistan Ziaulhaq Rashidi1, Dr

Saudi Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences Abbreviated Key Title: Saudi J Humanities Soc Sci ISSN 2415-6256 (Print) | ISSN 2415-6248 (Online) Scholars Middle East Publishers, Dubai, United Arab Emirates Journal homepage: http://scholarsmepub.com/sjhss/ Original Research Article Nation Building Process in Afghanistan Ziaulhaq Rashidi1, Dr. Gülay Uğur Göksel2 1M.A Student of Political Science and International Relations Program 2Assistant Professor, Istanbul Aydin University, Istanbul, Turkey *Corresponding author: Ziaulhaq Rashidi | Received: 04.04.2019 | Accepted: 13.04.2019 | Published: 30.04.2019 DOI:10.21276/sjhss.2019.4.4.9 Abstract In recent times, a number of countries faced major cracks and divisions (religious, ethnical and geographical) with less than a decade war/instability but with regards to over four decades of wars and instabilities, the united and indivisible Afghanistan face researchers and social scientists with valid questions that what is the reason behind this unity and where to seek the roots of Afghan national unity, despite some minor problems and ethnic cracks cannot be ignored?. Most of the available studies on nation building process or Afghan nationalism have covered the nation building efforts from early 20th century and very limited works are available (mostly local narratives) had touched upon the nation building efforts prior to the 20th. This study goes beyond and examine major struggles aimed nation building along with the modernization of state in Afghanistan starting from late 19th century. Reforms predominantly the language (Afghani/Pashtu) and role of shared medium of communication will be deliberated. In addition, we will talk how the formation of strong centralized government empowered the state to initiate social harmony though the demographic and geographic oriented (north-south) resettlement programs in 1880s and how does it contributed to the nation building process. -

Round 18 - Tossups

NSC 2019 - Round 18 - Tossups 1. The only two breeds of these animals that have woolly coats are the Hungarian Mangalica ("man-gahl-EE-tsa"), and the extinct Lincolnshire Curly breed. Fringe scientist Eugene McCarthy posits that humans evolved from a chimp interbreeding with one of these animals, whose bladders were once used to store paint and to make rugby balls. One of these animals was detained along with the Chicago Seven after (*) Yippies nominated it for President at the 1968 DNC. A pungent odor found in this animal's testes is synthesized by truffles, so these animals are often used to hunt for them. Zhu Bajie resembles this animal in the novel Journey to the West. Foods made from this animal include rinds and carnitas. For 10 points, name these animals often raised in sties. ANSWER: pigs [accept boars or swine or hogs or Sus; accept domestic pigs; accept Pigasus the Immortal] <Jose, Other - Other Academic and General Knowledge> 2. British explorer Alexander Burnes was killed by a mob in this country's capital, supposedly for his womanizing. In this country, Malalai legendarily rallied troops at the Battle of Maiwand against a foreign army. Dr. William Brydon was the only person to survive the retreat of Elphinstone's army during a war where Shah Shuja was temporarily placed on the throne of this country. The modern founder of this country was a former commander under Nader Shah named (*) Ahmad Shah Durrani. This country was separated from British holdings by the Durand line, which separated its majority Pashtun population from the British-controlled city of Peshawar. -

Hajji Din Mohammad Biography

Program for Culture & Conflict Studies www.nps.edu/programs/ccs Hajji Din Mohammad Biography Hajji Din Mohammad, a former mujahedin fighter from the Khalis faction of Hezb-e Islami, became governor of the eastern province of Nangarhar after the assassination of his brother, Hajji Abdul Qadir, in July 2002. He is also the brother of slain commander Abdul Haq. He is currently serving as the provincial governor of Kabul Province. Hajji Din Mohammad’s great-grandfather, Wazir Arsala Khan, served as Foreign Minister of Afghanistan in 1869. One of Arsala Khan's descendents, Taj Mohammad Khan, was a general at the Battle of Maiwand where a British regiment was decimated by Afghan combatants. Another descendent, Abdul Jabbar Khan, was Afghanistan’s first ambassador to Russia. Hajji Din Mohammad’s father, Amanullah Khan Jabbarkhel, served as a district administer in various parts of the country. Two of his uncles, Mohammad Rafiq Khan Jabbarkhel and Hajji Zaman Khan Jabbarkhel, were members of the 7th session of the Afghan Parliament. Hajji Din Mohammad’s brothers Abdul Haq and Hajji Abdul Qadir were Mujahedin commanders who fought against the forces of the USSR during the Soviet Occupation of Afghanistan from 1980 through 1989. In 2001, Abdul Haq was captured and executed by the Taliban. Hajji Abdul Qadir served as a Governor of Nangarhar Province after the Soviet Occupation and was credited with maintaining peace in the province during the years of civil conflict that followed the Soviet withdrawal. Hajji Abdul Qadir served as a Vice President in the newly formed post-Taliban government of Hamid Karzai, but was assassinated by unknown assailants in 2002.