Lee Kuan Yew and the “Asian Values” Debate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

East Asian Economies and Their Philosophy Behind Success: Manifestation of Social Constructs in Economic Policies

Journal of International Studies © Foundation of International Studies, 2017 © CSR, 2017 Scientific Papers Lajčiak, M. (2017). East Asian economies and their philosophy behind success: Journal Manifestation of social constructs in economic policies . Journal of International Studies, of International 10(1), 180-192. doi:10.14254/2071-8330.2017/10-1/13 Studies © Foundation East Asian economies and their philosophy of International Studies, 2017 behind success: Manifestation of social © CSR, 2017 Scientific Papers constructs in economic policies Milan Lajčiak Ambassador of the Slovak Republic to the Republic of Korea Slovak Embassy in Seoul, South Korea [email protected] Abstract. The study contributes to broader conceptualization of East Asian Received: December, 2016 economies by elaboration of sociocultural and institutional approaches, 1st Revision: explaining differences between Western and East Asian geography of thinking January, 2017 and focusing on the manifestations of Confucian values and their social Accepted: February, 2017 constructs into organizational patterns of economic policies and business culture within East Asian economies. The analysis demonstrates that these factors has DOI: strongly impacted successful industrialization processes in East Asian countries 10.14254/2071- and served as a strategic comparative advantage in their economic developmental 8330.2017/10-1/13 endeavor. The paper is claiming that economic policies of the region would never be so effective if they would not be integrated into social organizational models of these countries. The ability of East Asian leaders to understand weaknesses and strengths of their societies in terms of market forces and to tap on their potential through economic policies was a kind of philosophy behind their success. -

Jcci Singapore Foundation 2020年度 基金への寄付のお願い

JCCI SINGAPORE FOUNDATION 2020年度 基金への寄付のお願い FUNDRAISING APPEAL JCCI SINGAPORE FOUNDATION LIMITED C/O JAPANESE CHAMBER OF COMMERCE & INDUSTRY, SINGAPORE 2020年度 基金への寄付のお願い FUNDRAISING APPEAL 目次 CONTENTS 1. 寄付のお願い Fundraising Appeal 1 2. 基金の使途についての基本的な考え方 Purpose of Fundraising 3 3. 2020 年度募金要領・IPC ステータスの利用について Fundraising Details & About Donating to Institution of Public Character (IPC) 5 4. 2019 年収支決算および 2020 年収支予算 Summary of 2019 Year End Statement & 2020 Budget 7 5. 2020 年度組織図 Organisational Chart of Year 2020 9 6. 2019 年度 寄付・奨学金 結果報告 Sponsorships & Scholarships Report of Year 2019 12 7. 寄付実績一覧(1990 年~2019 年) List of Sponsorships and Awards 16 8. 奨学金実績一覧(1996 年~2019 年) List of JCCI Scholars 26 9. 2019 年度募金 結果報告 Fundraising Results of Year 2019 28 2020 年 8 月 会員各位 シンガポール日本商工会議所 会 頭 石垣 吉彦 副会頭・基金募金委員長 宇野 幹彦 シンガポール日本商工会議所基金 寄付のお願い 拝啓 時下ますますご清祥の段お慶び申し上げます。 平素より、弊商工会議所の事業活動に格別のご高配を賜り、厚く御礼を申し上げます。 ご高承の通り弊所の基金は、1990 年 5 月に在外商工会議所としては初めて設立され、以来 30 年間に亘りシンガポールの文化、芸術、スポーツ、教育分野の団体・個人に対し計 968 万Sドル の寄付を行って参りました。こうした功績はシンガポール政府や各種機関からも高く評価されて いるところです。 昨年度、当基金では、会員企業の皆様より約 27 万 4 千 S ドルの浄財を頂戴し、積立金からの拠 出を含めて約 37 万 5 千Sドルを、シンガポール社会への寄付やシンガポール人学生の日本留学の ための奨学金として活用させて頂きました。 2020 年度の募金目標については、基金管理委員会及び募金委員会で慎重に検討し、28 万 S ドル に設定いたしました。併せて、本年度も幅広い会員の皆様からのご協力をお願いしたく、寄付金 額を損金算入することができる「IPC ステータス」をご活用頂ければと存じます。また、拠出先 の選定等にあたりましても、一人でも多くのシンガポールの方々に喜んで頂けるような支援とな るよう、従来以上に真摯に考えて参りたいと存じます。 本所基金活動の趣旨をご理解賜り、引き続き 2020 年の募金におきましても、何卒、特段のご協 力をお願い申し上げます。 敬 具 ※本件担当・お問い合わせ先:シンガポール日本商工会議所基金 事務局(清水・リンゴ: [email protected]) 募金締切日:2020 年 11 月 30 日(当方入金確認時点)とさせて頂いております。 1 August 2020 Japanese Chamber of Commerce & Industry, Singapore President, Yoshihiko Ishigaki Vice President / Chairman of JCCI Singapore Foundation Fundraising Committee, Motohiko Uno JCCI SINGAPORE FOUNDATION FUNDRAISING APPEAL First and foremost, thank you for your continued support to the fundraising campaigns of JCCI Singapore Foundation c/o Japanese Chamber of Commerce & Industry, Singapore for the past years. -

Indonesia's Transformation and the Stability of Southeast Asia

INDONESIA’S TRANSFORMATION and the Stability of Southeast Asia Angel Rabasa • Peter Chalk Prepared for the United States Air Force Approved for public release; distribution unlimited ProjectR AIR FORCE The research reported here was sponsored by the United States Air Force under Contract F49642-01-C-0003. Further information may be obtained from the Strategic Planning Division, Directorate of Plans, Hq USAF. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rabasa, Angel. Indonesia’s transformation and the stability of Southeast Asia / Angel Rabasa, Peter Chalk. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. “MR-1344.” ISBN 0-8330-3006-X 1. National security—Indonesia. 2. Indonesia—Strategic aspects. 3. Indonesia— Politics and government—1998– 4. Asia, Southeastern—Strategic aspects. 5. National security—Asia, Southeastern. I. Chalk, Peter. II. Title. UA853.I5 R33 2001 959.804—dc21 2001031904 Cover Photograph: Moslem Indonesians shout “Allahu Akbar” (God is Great) as they demonstrate in front of the National Commission of Human Rights in Jakarta, 10 January 2000. Courtesy of AGENCE FRANCE-PRESSE (AFP) PHOTO/Dimas. RAND is a nonprofit institution that helps improve policy and decisionmaking through research and analysis. RAND® is a registered trademark. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions or policies of its research sponsors. Cover design by Maritta Tapanainen © Copyright 2001 RAND All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, -

Do Asian Values Deter Popular Support for Democracy? the Case of South Korea

A Comparative Survey of DEMOCRACY, GOVERNANCE AND DEVELOPMENT Working Paper Series: No. 26 Do Asian Values Deter Popular Support for Democracy? The Case of South Korea Chong-Min Park Korea University Doh Chull Shin University of Missouri Issued by Asian Barometer Project Office National Taiwan University and Academia Sinica 2004 Taipei Asian Barometer A Comparative Survey of Democracy, Governance and Development Working Paper Series The Asian Barometer (ABS) is an applied research program on public opinion on political values, democracy, and governance around the region. The regional network encompasses research teams from twelve East Asian political systems (Japan, Mongolia, South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, China, the Philippines, Thailand, Vietnam, Cambodia, Singapore, and Indonesia), and five South Asian countries (India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and Nepal). Together, this regional survey network covers virtually all major political systems in the region, systems that have experienced different trajectories of regime evolution and are currently at different stages of political transition. The ABS Working Paper Series is intended to make research result within the ABS network available to the academic community and other interested readers in preliminary form to encourage discussion and suggestions for revision before final publication. Scholars in the ABS network also devote their work to the Series with the hope that a timely dissemination of the findings of their surveys to the general public as well as the policy makers would help illuminate the public discourse on democratic reform and good governance. The topics covered in the Series range from country-specific assessment of values change and democratic development, region-wide comparative analysis of citizen participation, popular orientation toward democracy and evaluation of quality of governance, and discussion of survey methodology and data analysis strategies. -

Deakin University

AUSTRALIA & INDONESIA: BEYOND STABILITY, TOWARDS ORDER Scott Burchill & Darnien Kingsbury Although Indonesia is Australia's largest and most important neighbour, the relationship between the two profoundly different societies has been punctuated by bouts of high tension, suspicion and mutual mistrust. In the late 1940s the Chifley Government was openly supportive of the emerging nationalist elite in Jakarta, to the point that Indonesia's foreign minister Subandrio later described Australia as the "mid-wife" at the birth of the Indonesian republic. However, despite Australia's diplomatic support for the de-colonisation of the Dutch East Indies after the Second World War, Canberra and Jakarta have experienced a troubled diplomatic relationship virtually since Indonesia's independence.' Attempts to resolve enduring problems and recast the bilateral relationship in a more positive light have been a recurring theme in Australian diplomatic and academic circles since the 1950s. And yet despite considerable effort on both sides, remarkably little progress has been made in constructing a long term engagement which satisfies the expectations and aspirations of both peoples. This paper seeks to identify the structural faults in the architecture of the relationship and explore both the opportunities and limits of future co-operation. It will be argued that before a more mutually satisfactory and successful relationship can be built, new foundations of understanding will need to be laid. This presupposes a recognition of earlier faults which have periodically led to diplomatic cracks in the relationship and prevented enduring levels of civility from developing. From an Australian perspective, this paper assesses the prospects of co-existence between two independent political communities, one an advanced industrial liberal democracy, the other a developing non-liberal society. -

Confucianism and Democratization in East Asia: Reassessing the Asian Values Debate

Confucianism and Democratization in East Asia: Reassessing the Asian Values Debate Doh Chull Shin Center for the Study of Democracy University of California Irvine, California U. S. A. Prepared for presentation at a symposium on “Confucianism, Democracy, and Constitutionalism” to be held in National Taiwan University on June 14-15, 2013, Taipei, Taiwan. This is only a draft. Please do not quote without author’s permission. Confucianism and Democratization in East Asia: Reassessing the Asian Values Debate Today, East Asia represents a region of democratic underdevelopment. More than three decades after the third wave of democratization began to spread from Southern Europe, much less than half the countries (six of sixteen) in the region meet the minimum criteria for electoral democracy. This ratio is much lower than the worldwide average of six democracies for every ten countries. Why does a region, blessed with rapid economic development, remain cursed with democratic underdevelopment? What makes it hard for democracy to take root in the region known as culturally Confucian Asia? To explain a lack of democratic development in the region, many scholars and political leaders have often promoted Confucian values as Asian values, and vigorously debated their influence, either actual or potential, on the democratic transformation of authoritarian regimes in the region from a variety of perspectives. For decades, politicians and scholars have vigorously debated whether Confucian cultural legacies have served to deter the democratization of authoritarian regimes in the region. Lee Kuan Yew (2000) and other proponents of the Asian Values thesis, for example, have claimed that Western-style liberal democracy is neither suitable for nor compatible with the Confucianism of East Asia, where collective welfare, a sense of duty, and other principles of Confucian moral philosophy run deep in people’s consciousness. -

Parsis and Zoroastrianism in Singapore Text by Ernest K.W

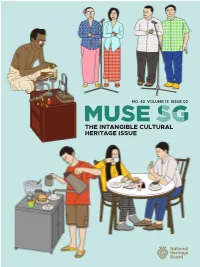

NO. 42 VOLUME 13 ISSUE 02 THE INTANGIBLE CULTURAL HERITAGE ISSUE Explore Singapore through NHB’s self-guided heritage trails! Booklets and maps are downloadable at www.roots.gov.sg/nhb/trails. FOREWORD elcome to the second and final edition of the Intangible Cultural PUBLISHER Heritage (ICH) series of MUSE SG, which explores Singapore’s multi-faceted range of ICH practices. In this issue, we continue toW uncover seven more ICH practices through the efforts of students from the National University of Singapore’s History Society and Nanyang Technological University. National Heritage Board 61 Stamford Road, #03-08, Stamford Court, We examine the craft of traditional Indian goldsmithing in Singapore, long Singapore 178892 associated with jewellery shops and ateliers in the Little India area. We uncover some of its many connections to religion, culture and social practices. Another CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER Chang Hwee Nee link to India and its long, intersecting history with Singapore and Southeast Asia can be found in our article on Parsis and Zoroastrianism. Adherents of DEPUTY CHIEF EXECUTIVE one of the oldest monotheistic religions in the world, the Zoroastrian Parsi Alvin Tan (Policy & Community) community in Singapore is flourishing. MUSE SG TEAM Director, Education & Community Outreach The theme of diverse cultures and their meeting points continues with articles Wai Yin Pryke on celebrations of the Jewish Passover in Singapore, reimagining traditional Chinese music in Singapore, and the Peranakan community’s love and Editors Norsaleen Salleh adoption of the Malay performing art of dondang sayang. Tan Jeng Woon Royston Lin Food is never far from discussions of heritage in Singapore, and the classic Nanyang breakfast of kaya toast and kopi is well-loved by a wide cross-section DESIGN & LAYOUT Oneplusone of people from across multiple cultures here. -

EAST ASIA FORUM QUARTERLY JANUARY — MARCH 2018 Relevance at Risk Picture: Jorge Silva / Reuters

EASTECONOMICS, POLITICS and PUBLICASIA POLICY IN East ASIA andFORUM the PACIFIC Vol.10 No.1 January–March 2018 $9.50 Quarterly Why ASEAN matters Gary Clyde Hufbauer Success ensures long-term importance to the US Jayant Menon Trade: regional means, global objectives Tan See Seng A defence of ADMM Plus Amy E. Searight How ASEAN matters in the age of Trump ... and more ASIAN REVIEW — Gareth Evans: Australia and geopolitical transition Stephen Costello: Only Seoul can lead Korean integration EASTASIAFORUM CONTENTS 3 CHONG JA IAN Quarterly Still in the driver’s seat or asleep at the ISSN 1837-5081 (print) wheel? ISSN 1837-509X (online) 6 GARY CLYDE HUFBAUER From the Editors’ Desk Success ensures long-term importance to the US In recent times we’ve seen the United States retreat from leading 7 JAYANT MENON the global order and apparently reversing its pivot to Asia; the rise Regional means and global objectives of China with its aggressive stance on the South China Sea and its 9 ANTHONY MILNER infrastructure development ‘carrot’, the Belt and Road Initiative; a Culture and values central to creating deeper putative ‘Quad’ configuration of Indo-Pacific power around the US, partnership India, Japan and Australia; and a hot spot in North Korea. Given all 11 AMY E. SEARIGHT this and continued US–China rivalry for regional leadership, what How ASEAN matters in the age of Trump role can ASEAN play? How viable is ASEAN centrality, given the 13 GARETH EVANS diversity of its members and its new challenges? ASIAN REVIEW: Australia in an age of In this EAFQ we examine these questions first from the outside, geopolitical transition comparing the substance of US repositioning with its rhetoric 15 PHILIPS J. -

PSG Enrichment Programmes

• For enquiries, contact the respective course provider(s) as listed in the Course Listing Table (overleaf) • Complete the registration form(s) attached (end of this prospectus) • Whatsapp to the vendor(s) or to Nick (9018 9413) to receive details for payment via phone/internet banking Tentative commencement dates for Sat & Sun classes will be 16th & 17th Jan 2021 respectively General Enquires Nick 9018 9413 For Semester 1, 2021 Programme Provider A / Course Name & Fees Contacts Lesson Timing Chinese Enrichment (code* : 01) Best Mandarin Enrichment P1 Sat 1200 – 1330 Centre P2 Sat 0900 – 1030 Fee (for 18 lessons): $240 P3 Sat 1200 – 1330 Ms Zhao 9295 2536 P4 Sat 1030 – 1200 P5 Sat 0900 1030 Ms Chen 9487 3258 – P6 Sat 1030 – 1200 English Enrichment (code: 02) Yap Poh Hua P1 Sat 0900 – 1030 P2 Sat 1030 – 1200 Fee (for 18 lessons): $240 P3 Sat 0900 – 1030 Ms Yap 9836 6485 P4 Sat 1200 – 1330 P5 Sat 1030 – 1200 P6 Sat 1200 – 1330 Math Enrichment (code: 03) ARC Centre P1 Sat 1030 – 1200 P2 Sat 0900 – 1030 Fee (for 18 lessons): $250 Ms Marissa 8511 3135 P3 Sat 1030 – 1200 P4 Sat 0900 – 1030 P2 Sun 0830 – 1000 Math Olympiad (code: 04) RECMEL - Resource Centre for P3 Sun 1130 – 1300 Math Educators and Learners P4 Sun 1000 – 1130 Fee (for 18 lessons): $260 P5 Sun 0830 – 1000 Mr Michael Gan 9787 1523 P6 Sun 1000 – 1130 P3 Sun 1000 – 1130 Science Enrichment (code: 05) P4 Sun 0830 – 1000 P5 Sun 1000 – 1130 Fee (for 18 lessons): $250 Ms Marissa 8511 3135 P6 Sun 0830 – 1000 Children Art Class (code: 06) Zhuole Art Studio Beginner Sat 1030 – 1200 (P1 -

We, the Citizens of Singapore Pledge Ourselves As One United People

We, the citizens of Singapore Pledge ourselves as one united people Regardless of race, language, or religion To build a democratic society Based on justice and equality So as to achieve happiness, prosperity and progress For our nation — National Pledge of Singapore, 1966 by S. Rajaratnam (1915 – 2006), then Minister for Foreign Affairs and a founding father of modern Singapore RETHINKING ALBERT O. HIRSCHMAN’S ‘EXIT, VOICE, AND LOYALTY’: THE CASE OF SINGAPORE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctorate of Philosophy in The Graduate School at The Ohio State University By Selina Sher Ling Lim, MA, B.Soc.Sci. (Hons.), B.Sc. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2007 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor R. William Liddle, Adviser Professor Anthony Mughan Emeritus Professor Patrick B. Mullen Adviser Graduate Program of Political Science Copyright by Selina Sher Ling Lim 2007 ABSTRACT This research explores the concept of national loyalty within today’s context of international migration and globalization. It seeks to provide a systematic understanding of national loyalty that, thus far, has been widely accepted by most citizens as a social fact and assumed to be an inherent trait. Probing deeper, however, we realize that our understanding of national loyalty is superficial, made ever more shaky by today’s ease of international travel, increasingly porous territorial borders, and images of the global citizen who is at home anywhere in the world. Academically, our understanding of national loyalty has also been mired in intellectual, philosophical, and rhetorical debates over the concept of the nation and national identity. Still, the realization that national loyalty is particularly vital during times when the nation-state is at some major cross road, or faced with the greatest challenge ever yet, is not lost on political leaders throughout the world, especially since the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, on the World Trade Center in New York. -

Southeast Asia and the Politics of Vulnerability

Third World Quarterly, Vol 23, No 3, pp 549–564, 2002 Southeast Asia and the politics of vulnerability MARK BEESON ABSTRACT The economic and political crises that have engulfed Southeast Asia over recent years should not have come as such a surprise. A consideration of the region’s historical position and economic development demonstrates just what formidable obstacles still constrain the nations of Southeast Asia as they attempt to restore growth and stability. This paper places the Southeast Asian experience in historical context, outlines the political and economic obstacles that continue to impede development, and considers some of the initiatives that have been undertaken at a regional level in the attempt to maintain a degree of stability and independence. Despite the novelty and potential importance of initiatives like the Asean +3 grouping, this paper argues that the continuing economic and strategic vulnerability of the Southeast Asian states will continue to profoundly shape their politics and limit their options. The economic and political crises that have recently engulfed the countries of Southeast Asia provide a stark reminder of just how difficult the challenge of sustained regional development remains. In retrospect, the hyperbole that surrounded the ‘East Asian miracle’ looks overblown, and testimony to the manner in which rhetoric can outstrip reality, especially in the minds of inter- national investors. Certainly, some observers had questioned the depth and resilience of capitalist development in Southeast Asia, 1 but in the years immediately before 1997 such analyses tended to be in the minority. Now, of course, it is painfully obvious that much of Southeast Asia’s economic and political development was extremely fragile. -

Asian Values: a Pertinent Concept to Explain Economic Development of East Asia? Dong Hyeon Jung Pusan National University, South Korea, [email protected]

Comparative Civilizations Review Volume 51 Article 8 Number 51 Fall 2004 10-1-2004 Asian Values: A pertinent Concept to Explain Economic Development of East Asia? Dong Hyeon Jung Pusan National University, South Korea, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr Recommended Citation Jung, Dong Hyeon (2004) "Asian Values: A pertinent Concept to Explain Economic Development of East Asia?," Comparative Civilizations Review: Vol. 51 : No. 51 , Article 8. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr/vol51/iss51/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the All Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Comparative Civilizations Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Jung: Asian Values: A pertinent Concept to Explain Economic Development Dong Hyeon Jung 107 ASIAN VALUES: A PERTINENT CONCEPT TO EXPLAIN ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT IN EAST ASIA? DONG HYEON JUNG (DEPT. OF ECONOMICS, PUSAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY, SOUTH KOREA) [email protected] I. Introduction: Debates on Asian Values Some time after the economic crisis of East Asia in 1997, debates over Asian Values (of Confucian origin) have emerged again in Korea, many of them about how much Asian Values are responsible for suc- cessful economic development in Korea and other East Asian countries. These debates, to some degree, are an answer to Western criticism of Asian Values, which are seen to be responsible for "crony capitalism" and the consequences of the Asian economic crisis. Asian Values, for which a clear definition is not yet available, is generally conceived as a combination of a strong state and political authority, education and self- cultivation, frugality and thrift, an ethic of hard work and labor disci- pline, social harmony and group-responsibility—in short, as a form of social civility which shows distinctive features of Confucianism.