713 00A Globalization and Labour Pre.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Industrial Action

Dewi Hardiningtyas, ST, MT, MBA Industrial Action LOGO Source of Industrial Conflict Internal External Style of management Economic policy Physical environment Labor legislation Social relationship Political issue Other facilities National crisis Grievance Social inequalities Industrial Action Industrial action refers collectively to any measure taken by trade unions or other organized labor meant to reduce productivity in a workplace. UK, Ireland and Australia Industrial action US Job action I L O Standards Convention No. 87 the right of trade unions as organizations of workers set up to further and defend their occupational interests (Article 10), to formulate their programs and organize their activities (Article 3). This means that unions have the right to negotiate with employers and to express their views on economic and social issues affecting the occupational interests of their members. J.-M. Servais, “ILO standards on freedom of association and their implementation”, International Labor Review, Vol. 123(6), Nov.–Dec. 1984, pp. 765–781. Types of Industrial Action Occupation Strike Work-to-Rule of Factories General Overtime Slowdown Strike Ban 1. Strike Strike action (labor strike) is a work stoppage caused by the mass refusal of employees to work. A strike usually takes place in response to employee grievances. Wildcat Strike (Poole, 1980) This form of strike is in violation of contract and not authorized by the union because no reason or notice is given to employer before embarking 2009, Lindsay Oil on it. Refinery strike Sit-down Strike (Poole, 1980) This is type of strike involve workers being present at work but literally not working. 1930, Flint sit-down strike by the United Auto workers Constitutional vs Unconstitutional Strike (Poole, 1980) Constitutional Strike Unconstitutional Strike This refers to actions that This is a strike action that conform to the due does not conform to the procedure of the collective provisions of the collective agreement. -

Recorder 298.Pages

RECORDER RecorderOfficial newsletter of the Melbourne Labour History Society (ISSN 0155-8722) Issue No. 298—July 2020 • From Sicily to St Lucia (Review), Ken Mansell, pp. 9-10 IN THIS EDITION: • Oil under Troubled Water (Review), by Michael Leach, pp. 10-11 • Extreme and Dangerous (Review), by Phillip Deery, p. 1 • The Yalta Conference (Review), by Laurence W Maher, pp. 11-12 • The Fatal Lure of Politics (Review), Verity Burgmann, p. 2 • The Boys Who Said NO!, p. 12 • Becoming John Curtin and James Scullin (Review), by Nick Dyrenfurth, pp. 3-4 • NIBS Online, p. 12 • Dorothy Day in Australia, p. 4 • Union Education History Project, by Max Ogden, p. 12 • Tribute to Jack Mundey, by Verity Burgmann, pp. 5-6 • Graham Berry, Democratic Adventurer, p. 12 • Vale Jack Mundey, by Brian Smiddy, p. 7 • Tribune Photographs Online, p. 12 • Batman By-Election, 1962, by Carolyn Allan Smart & Lyle Allan, pp. 7-8 • Melbourne Branch Contacts, p. 12 • Without Bosses (Review), by Brendan McGloin, p. 8 Extreme and Dangerous: The Curious Case of Dr Ian Macdonald Phillip Deery His case parallels that of another medical doctor, Paul Reuben James, who was dismissed by the Department of Although there are numerous memoirs of British and Repatriation in 1950 for opposing the Communist Party American communists written by their children, Dissolution Bill. James was attached to the Reserve Australian communists have attracted far fewer Officers of Command and, to the consternation of ASIO, accounts. We have Ric Throssell’s Wild Weeds and would most certainly have been mobilised for active Wildflowers: The Life and Letters of Katherine Susannah military service were World War III to eventuate, as Pritchard, Roger Milliss’ Serpent’s Tooth, Mark Aarons’ many believed. -

Workers and Labour in a Globalised Capitalism

Workers and Labour in a Globalised Capitalism MANAGEMENT, WORK & ORGANISATIONS SERIES Series editors: Gibson Burrell, School of Management, University of Leicester, UK Mick Marchington, Manchester Business School, University of Manchester and Strathclyde Business School, University of Strathclyde, UK Paul Thompson, Strathclyde Business School, University of Strathclyde, UK This series of textbooks covers the areas of human resource management, employee relations, organisational behaviour and related business and management fields. Each text has been specially commissioned to be written by leading experts in a clear and accessible way. The books contain serious and challenging material, take an analytical rather than prescriptive approach and are particularly suitable for use by students with no prior specialist knowledge. The series is relevant for many business and management courses, including MBA and post-experience courses, specialist masters and postgraduate diplomas, professional courses and final-year undergraduate courses. These texts have become essential reading at business and management schools worldwide. Published titles include: Maurizio Atzeni WORKERS AND LABOUR IN A GLOBALISED CAPITALISM Stephen Bach and Ian Kessler THE MODERNISATION OF THE PUBLIC SERVICES AND EMPLOYEE RELATIONS Emma Bell READING MANAGEMENT AND ORGANIZATION IN FILM Paul Blyton and Peter Turnbull THE DYNAMICS OF EMPLOYEE RELATIONS (3RD EDN) Paul Blyton, Edmund Heery and Peter Turnbull (eds) REASSESSING THE EMPLOYMENT RELATIONSHIP Sharon C. Bolton EMOTION -

Hitchhiking: the Travelling Female Body Vivienne Plumb University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2012 Hitchhiking: the travelling female body Vivienne Plumb University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Plumb, Vivienne, Hitchhiking: the travelling female body, Doctorate of Creative Arts thesis, School of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, 2012. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/3913 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Hitchhiking: the travelling female body A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree Doctorate of Creative Arts from UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG by Vivienne Plumb M.A. B.A. (Victoria University, N.Z.) School of Creative Arts, Faculty of Law, Humanities & the Arts. 2012 i CERTIFICATION I, Vivienne Plumb, declare that this thesis, submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Creative Arts, in the Faculty of Creative Arts, School of Journalism and Creative Writing, University of Wollongong, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Vivienne Plumb November 30th, 2012. ii Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge the support of my friends and family throughout the period of time that I have worked on my thesis; and to acknowledge Professor Robyn Longhurst and her work on space and place, and I would also like to express sincerest thanks to my academic supervisor, Dr Shady Cosgrove, Sub Dean in the Creative Arts Faculty. Finally, I would like to thank the staff of the Faculty of Creative Arts, in particular Olena Cullen, Teaching and Learning Manager, Creative Arts Faculty, who has always had time to help with any problems. -

Unions Talk Tough at US Social Forum

Starbucks charged Chicago Couriers: doing Boycott Molson beer, IWW meets Bangladeshi again for firing IWW solidarity unionism support Alberta strike garment workers 5 6-7 9 11 INDUSTRIAL WORKER OFFICIAL NEWSPAPER O F T H E I N D U S T R I A L W O R K E R S O F T H E W O RLD August 2007 #1698 Vol. 104 No. 8 $1 / £1 / €1 Unions talk tough at US Social Forum By Jerry Mead-Lucero Big Labor’s involvement in the social nizers were forced to compromise with the ILO (International Labour Organi- “What is happening in America forum process, since the first few World police on a much less confrontational zation). In April, the ILO declared the to workers today is the result of a Social Forums in Porto Alegre, Brazil, route due to the opposition of much North Carolina ban on public sector thirty year sustained, intentional, has served as a way for the AFL-CIO and of Atlanta ’s business community. A collective bargaining a violation of strategic, assault on workers, unions, many of the union internationals to mix destination in the original plan was international labor standards and called our quality of life and our standard of and mingle with activists from a broad Grady Hospital, where the green-shirted for repeal of North Carolina General living. It has been a class war against range of social struggles. The same can members of Local 1644 had planned Statute 95-98, the basis of the ban. workers and it is time we engage that be said of the relatively impressive sup- to express their opposition to a recent Traditionally, social forum planners class war and fought back.” port given to the first USSF by organized decision by the Chamber of Commerce and participants will engage in a num- These words were met by a labor. -

Solidarity Unionism : Rebuilding the Labor Movement from Below, Second Edition Pdf Free Download

SOLIDARITY UNIONISM : REBUILDING THE LABOR MOVEMENT FROM BELOW, SECOND EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Staughton Lynd | 122 pages | 21 May 2015 | PM Press | 9781629630960 | English | Oakland, United States Solidarity Unionism : Rebuilding the Labor Movement from Below, Second Edition PDF Book There is a remainder mark on top of the text block and appx. An oral history project of the working class undertaken with his wife inspired Lynd to earn a JD from the University of Chicago in One of them, an electric lineman, returned with a fellow worker to help bring electric power to small towns in northern Nicaragua. Zachary McDargh rated it really liked it Aug 06, Create a Want BookSleuth Can't remember the title or the author of a book? Editors: Aziz Choudry and Adrian A. While many lament the decline of traditional unions, Lynd takes succor in the blossoming of rank- and-file worker organizations throughout the world that are countering rapacious capitalists and those comfortable labor leaders that think they know more about work and struggle than their own members. Isn't the whole point of forming a union to get a written collective bargaining agreement? New books! Far from prefiguring a new society, they are institutional dinosaurs, resembling nothing so much as the corporations we are striving to replace. Staughton Lynd practiced employment law for twenty years in Youngstown, Ohio. Kersplebedeb Left-Wing Books and more! This has been the model of the Industrial Workers of the World for over years and is also the way many workers centers operate. Lynd doesn't seem to consider the possibility that some workers may not be looking for constant class warfare on the job, and that settling a decent contract offers a much needed respite to lock-in gains. -

Revitalization Strategy of Labor Movements

<Abstract> Revitalization Strategy of Labor Movements Korea Labour & Society Institute 1. The stagnation of trade union movement is an international phenomenon. The acceleration of globalization and technological innovation, the expanding predominance of service industries in the economies of advanced industrialised countries and the concomitant shifts in the composition of employment, and the deepening of neoliberal policy climate in the context of economic slow-down, which have prevailed since the 1980s, have all contributed to the stagnation of trade union movement in most countries across the world. This phenomenon has been captured through such indicators as the decline in union density, the weakening of political and social influence, and decentralisation of collective bargaining have been, among others. The trade union movements in different countries have, however, since 1990s, developed and undertaken a variety of "revitalisation"strategies to wake out of the stagnation. The specific shape of the revitalisation strategy were informed by the specific nature of the challenge the unions faced, the characteristics of the industrial relations system in which the unions were constituted, and the historical identity individual trade union movement espoused. However, organising efforts, internal innovation, social partnership, strengthening of political campaign activities, and extension of solidarity with civil society and community networks have featured as common components in most of the varied strategies. The evidence of these common initiatives points to the existence of some common challenge that courses through the country-specific situations the trade union movements in different countries have found themselves in. This study examines the strategic responses of the trade unions in the selected countries have undertaken in the face of the challenges faced by the international labour movement. -

The Making of White Australia

The making of White Australia: Ruling class agendas, 1876-1888 Philip Gavin Griffiths A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University December 2006 I declare that the material contained in this thesis is entirely my own work, except where due and accurate acknowledgement of another source has been made. Philip Gavin Griffiths Page v Contents Acknowledgements ix Abbreviations xiii Abstract xv Chapter 1 Introduction 1 A review of the literature 4 A ruling class policy? 27 Methodology 35 Summary of thesis argument 41 Organisation of the thesis 47 A note on words and comparisons 50 Chapter 2 Class analysis and colonial Australia 53 Marxism and class analysis 54 An Australian ruling class? 61 Challenges to Marxism 76 A Marxist theory of racism 87 Chapter 3 Chinese people as a strategic threat 97 Gold as a lever for colonisation 105 The Queensland anti-Chinese laws of 1876-77 110 The ‘dangers’ of a relatively unsettled colonial settler state 126 The Queensland ruling class galvanised behind restrictive legislation 131 Conclusion 135 Page vi Chapter 4 The spectre of slavery, or, who will do ‘our’ work in the tropics? 137 The political economy of anti-slavery 142 Indentured labour: The new slavery? 149 The controversy over Pacific Islander ‘slavery’ 152 A racially-divided working class: The real spectre of slavery 166 Chinese people as carriers of slavery 171 The ruling class dilemma: Who will do ‘our’ work in the tropics? 176 A divided continent? Parkes proposes to unite the south 183 Conclusion -

The Globalisation of the Pharmaceutical Industry

The Globalisation of the Pharmaceutical Industry PHARMACEUTICALS POLICY AND LAW Pharmaceuticals Policy and Law Volume 18 Earlier published in this series Vol.1. J.L. Valverde and G. Fracchia (Eds), Focus on Pharmaceutical Research Vol.2. J.L. Valverde (Ed), The Problem of Herbal Medicines Legal Status Vol.3. J.L. Valverde (Ed), The European Regulation on Orphan Medicinal Products Vol.4. J.L. Valverde (Ed), Information Society in Pharmaceuticals Vol.5. C. Huttin (Ed), Challenges for Pharmaceutical Policies in the 21st Century Vol.6. J.L. Valverde and P. Weissenberg (Eds), The Challenges of the New EU Pharmaceutical Legislation Vol.7. J.L. Valverde (Ed), Blood, Plasma and Plasma Proteins: A Unique Contribution to Modern Healthcare Vol.8. J.L. Valverde (Ed), Responsibilities in the Efficient Use of Medicinal Products Vol.9(1,2). J.L. Valverde (Ed), 2050: A Changing Europe. Demographic Crisis and Baby Friend Policies Vol.9(3,4). J.L. Valverde (Ed), Key Issues in Pharmaceuticals Law Vol.10. J.L. Valverde and D. Watters (Eds), Focus on Immunodeficiencies Vol.11(1,2). J.L. Valverde and A. Ceci (Eds), The EU Paediatric Regulation Vol.11(3). J.L. Valverde (Ed), Health Fraud and Other Trends in the EU Vol.11(4). J.L. Valverde (Ed), Rare Diseases: Focus on Plasma Related Disorders Vol.12(1,2). J.L. Valverde and A. Ceci (Eds), Innovative Medicine: The Science and the Regulatory Framework Vol.12(3,4). J.L. Valverde (Ed), New Developments of Pharmaceutical Law in the EU Vol.13(1,2). J.L. Valverde (Ed), Challenges for the Pharmaceuticals Policy in the EU Vol.14(1). -

Dr. Manmohan Singh Lays the Foundation Stone of Indian National Defence University by : INVC Team Published on : 23 May, 2013 10:20 PM IST

Dr. Manmohan Singh Lays the Foundation Stone of Indian National Defence University By : INVC Team Published On : 23 May, 2013 10:20 PM IST INVC, Delhi, ThePrime MinisterDr.Manmohan Singh today in an impressive function laid the foundation stone for the Indian National Defence University (INDU) at Binola, Gurgaon in Haryana. The event was attended among others by the Governor of Haryana Shri JagannathPahadia, Defence Minister Shri AK Antony, Minister of External Affairs Shri Salman Khurshid, Minister of Social Justice and EmpowermentMs.SeljaKumari, Minister of State for Defence Shri Jitendra Singh, Chief Minister of Haryana Shri Bhupinder Singh Hooda and the three Services Chiefs. The proposed Indian National Defence University spread over more than two hundred acres of land which will be fully functional in 2018 will be set up as a fully autonomous institution to be constituted under an Act of Parliament. While the President of India would act as the Visitor, the Defence Minister will be its Chancellor. It may be recalled that after the Kargil conflict, the government had set up a Review Committee, headed by eminent strategic expert K Subrahmanyam, which had recommended the establishment of a university to exclusively deal with defence and strategic matters. The aim of INDU would be to provide military leadership and other concerned civilian officials knowledge based higher education for management of the defence of India, and keeping them abreast with emerging security challenges through scholarly research & training. The INDU would develop and propagate higher education in Defence Studies, Defence Management, Defence Science and Technology and promote policy oriented research related to National Defence. -

Parties and Interest Associations Report Intra-Party Democracy, Association Competence (Business), Association Competence (Others)

Sustainable Governance Indicators SGI 2015 Parties and Interest Associations Report Intra-party Democracy, Association Competence (Business), Association Competence (Others) SGI 2015 | 2 Parties and Interest Associations Indicator Intra-party Democracy Question How inclusive and open are the major parties in their internal decision-making processes? 41 OECD and EU countries are sorted according to their performance on a scale from 10 (best) to 1 (lowest). This scale is tied to four qualitative evaluation levels. 10-9 = The party allows all party members and supporters to participate in its decisions on the most important personnel and issues. Lists of candidates and agendas of issues are open. 8-6 = The party restricts decision-making to party members. In most cases, all party members have the opportunity to participate in decisions on the most important personnel and issues. Lists of candidates and agendas of issues are rather open. 5-3 = The party restricts decision-making to party members. In most cases, a number of elected delegates participate in decisions on the most important personnel and issues. Lists of candidates and agendas of issues are largely controlled by the party leadership. 2-1 = A number of party leaders participate in decisions on the most important personnel and issues. Lists of candidates and agendas of issues are fully controlled and drafted by the party leadership. Denmark Score 8 Four of the political parties represented in the Danish parliament, the Liberal Party, the Social Democratic Party, the Social Liberal Party and the Conservative Party have existed for more than 100 years and have all regularly taken part in governments. -

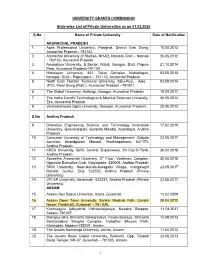

UNIVERSITY GRANTS COMMISSION State-Wise List of Private

UNIVERSITY GRANTS COMMISSION State-wise List of Private Universities as on 01.02.2020 S.No Name of Private University Date of Notification ARUNACHAL PRADESH 1. Apex Professional University, Pasighat, District East Siang, 10.05.2013 Arunachal Pradesh - 791102. 2. Arunachal University of Studies, NH-52, Namsai, Distt – Namsai 26.05.2012 - 792103, Arunachal Pradesh. 3. Arunodaya University, E-Sector, Nirjuli, Itanagar, Distt. Papum 21.10.2014 Pare, Arunachal Pradesh-791109 4. Himalayan University, 401, Takar Complex, Naharlagun, 03.05.2013 Itanagar, Distt – Papumpare – 791110, Arunachal Pradesh. 5. North East Frontier Technical University, Sibu-Puyi, Aalo 03.09.2014 (PO), West Siang (Distt.), Arunachal Pradesh –791001. 6. The Global University, Hollongi, Itanagar, Arunachal Pradesh. 18.09.2017 7. The Indira Gandhi Technological & Medical Sciences University, 26.05.2012 Ziro, Arunachal Pradesh. 8. Venkateshwara Open University, Itanagar, Arunachal Pradesh. 20.06.2012 S.No Andhra Pradesh 9. Bharatiya Engineering Science and Technology Innovation 17.02.2019 University, Gownivaripalli, Gorantla Mandal, Anantapur, Andhra Pradesh 10. Centurian University of Technology and Management, Gidijala 23.05.2017 Junction, Anandpuram Mandal, Visakhapatnam- 531173, Andhra Pradesh. 11. KREA University, 5655, Central, Expressway, Sri City-517646, 30.04.2018 Andhra Pradesh 12. Saveetha Amaravati University, 3rd Floor, Vaishnavi Complex, 30.04.2018 Opposite Executive Club, Vijayawada- 520008, Andhra Pradesh 13. SRM University, Neerukonda-Kuragallu Village, mangalagiri 23.05.2017 Mandal, Guntur, Dist- 522502, Andhra Pradesh (Private University) 14. VIT-AP University, Amaravati- 522237, Andhra Pradesh (Private 23.05.2017 University) ASSAM 15. Assam Don Bosco University, Azara, Guwahati 12.02.2009 16. Assam Down Town University, Sankar Madhab Path, Gandhi 29.04.2010 Nagar, Panikhaiti, Guwahati – 781 036.