Manchester's Northern Quarter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

14-1676 Number One First Street

Getting to Number One First Street St Peter’s Square Metrolink Stop T Northbound trams towards Manchester city centre, T S E E K R IL T Ashton-under-Lyne, Bury, Oldham and Rochdale S M Y O R K E Southbound trams towardsL Altrincham, East Didsbury, by public transport T D L E I A E S ST R T J M R T Eccles, Wythenshawe and Manchester Airport O E S R H E L A N T L G D A A Connections may be required P L T E O N N A Y L E S L T for further information visit www.tfgm.com S N R T E BO S O W S T E P E L T R M Additional bus services to destinations Deansgate-Castle field Metrolink Stop T A E T M N I W UL E E R N S BER E E E RY C G N THE AVENUE ST N C R T REE St Mary's N T N T TO T E O S throughout Greater Manchester are A Q A R E E S T P Post RC A K C G W Piccadilly Plaza M S 188 The W C U L E A I S Eastbound trams towards Manchester city centre, G B R N E R RA C N PARKER ST P A Manchester S ZE Office Church N D O C T T NN N I E available from Piccadilly Gardens U E O A Y H P R Y E SE E N O S College R N D T S I T WH N R S C E Ashton-under-Lyne, Bury, Oldham and Rochdale Y P T EP S A STR P U K T T S PEAK EET R Portico Library S C ET E E O E S T ONLY I F Alighting A R T HARDMAN QU LINCOLN SQ N & Gallery A ST R E D EE S Mercure D R ID N C SB T D Y stop only A E E WestboundS trams SQUAREtowards Altrincham, East Didsbury, STR R M EN Premier T EET E Oxford S Road Station E Hotel N T A R I L T E R HARD T E H O T L A MAN S E S T T NationalS ExpressT and otherA coach servicesO AT S Inn A T TRE WD ALBERT R B L G ET R S S H E T E L T Worsley – Eccles – -

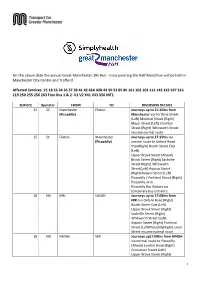

Road Closure

On the above date the annual Great Manchester 10k Run - incorporating the Half Marathon will be held in Manchester City Centre and Trafford. Affected Services: 15 18 33 34 36 37 38 41 42 42A 42B 43 50 53 85 86 101 102 103 111 142 143 197 216 219 250 255 256 263 Free Bus 1 & 2. V1 V2 X41 X43 X50 MT1 SERVICE Operator FROM TO DIVERSION DETAILS 15 SC Manchester Flixton Journeys up to 17:15hrs from (Piccadilly) Manchester via Portland Street (Left) Minshull Street (Right) Major Street (Left) Chorlton Street (Right) Whitworth Street resume normal route 15 SC Flixton Manchester Journeys up to 17:15hrs via (Piccadilly) normal route to Oxford Road then(Right) Booth Street East (Left) Upper Brook Street (Ahead) Brook Street (Right) Sackville Street (Right) Whitworth Street(Left) Aytoun Street (Right)Auburn Street (Left) Piccadilly / Portland Street (Right) Piccadilly in to Piccadilly Bus Station via temporary bus entrance 18 FM MRI NMGH Journeys up to 17:00hrs from MRI via Oxford Road (Right) Booth Street East (Left) Upper Brook Street (Right) Sackville Street (Right) Whitworth Street (Left) Aytoun Street (Right) Portland Street (Left)Piccadilly(Right) Lever Street resume normal route 18 FM NMGH MRI Journeys up17:00hrs from NMGH via normal route to Piccadilly (Ahead) London Road (Right) Grosvenor Street (Left) Upper Brook Street (Right) 1 Grafton Street (Left)Oxford Road resume normal route 33 FM Manchester Eccles From Shudehill Interchange (Left) (Shudehill) Shudehill (Left) Miller Street (Ahead) Cheetham Hill Road (Left) Trinity Way (Right) Regent -

Datagm Type: Website Organisation(S): GM Local Authorities, Open Data Manchester, GMFRS Tags: Open Data, Process, Standards, Website

Case Study: DataGM Type: Website Organisation(s): GM local authorities, Open Data Manchester, GMFRS Tags: open data, process, standards, website This was the earliest attempt in Greater Manchester to create a simple datastore that would hold important data from across the region, focussing on government transparency and providing better public services. The result was a highly functional datastore with which brought together data from a wider range of data publishers, and included a total of 371 datasets. It was ultimately not successful in creating a lasting basis for open data cooperation and access in Greater Manchester. However, it provides interesting lessons on how to proceed with future projects. Background DataGM was launched in February 2011, inspired by successful projects in North American cities, such as Track DC (now Open Data DC) in Washington, D.C. and Baltimore City Stats (now Open Baltimore). It was conceived as a one-stop-shop for key datasets on all aspects of city life. The programme emerged through a partnership between Trafford Council and the digital culture agency Future Everything. This began in 2009 when the Manchester Innovation Fund supported Future Everything to build open data innovation architecture in Greater Manchester, funded by NESTA, Manchester Council and the North West Regional Development Agency (now closed). Future Everything and Trafford Council in turn partnered with a wide range of data publishing organisations. These included local authority partners, as well as Greater Manchester Policy, Greater Manchester Fire and Rescue Service, Greater Manchester Passenger Transport Executive (now Transport for Greater Manchester), and the North West Strategic Health Authority. -

Brexit, Devolution and Economic Development in 'Left-Behind' Regions

Brexit, devolution and economic development in ‘left-behind’ regions John Tomaney* and Andy Pike+ *University College London, +Newcastle University https://doi.org/10.18573/wer.231 Accepted: 03/12/18 Introduction attention of policymakers. provide a poor measure of Finally, the politics of local real economic conditions in The Brexit vote in the UK, and regional economic these places. Considering according to Andrés development are considered, their high dependence upon Rodríguez-Pose (2018), is including the kinds of incapacity benefits paid to an instance of the revenge of institutions are required to those classified as unable to the ‘places that don’t matter’. affect a new economic future seek work, Beatty and This expression of discontent in such disadvantaged Fothergill estimate the ‘real’ from places at the sharp end places1. unemployment rates in such of rising social and spatial places to be 7.5% of the inequalities has fostered the The regional political working age population in rapid rise of populism that is economy of de- spring 2017. challenging the hegemony of industrialisation neoliberal capitalism and Educational disadvantage is liberal democracy. This Beatty and Fothergill (2018) concentred in left-behind paper considers the estimate that 16 million places (Education Policy problems of these so-called people live in the former Institute, 2018). This ‘left-behind’ places – typically industrial regions of the UK – disadvantage takes complex former industrial regions. almost one quarter of the and varied forms. For Such places figured national population. While instance, the North East prominently not just among these regions have shared in region consistently has those that voted leave in the the rise in employment in amongst the best primary Brexit referendum in the UK, recent years, growth rates in school results in the country, but also among those who London and other cities have but the lowest average adult voted for Donald Trump in been three times faster. -

Q05a 2011 Census Summary

Ward Summary Factsheet: 2011 Census Q05a • The largest ward is Cheetham with 22,562 residents, smallest is Didsbury West with 12,455 • City Centre Ward has grown 156% since 2001 (highest) followed by Hulme (64%), Cheetham (49%), Ardwick (37%), Gorton South (34%), Ancoats and Clayton (33%), Bradford (29%) and Moss Side (27%). These wards account for over half the city’s growth • Miles Platting and Newton Heath’s population has decreased since 2001(-5%) as has Moston (-0.2%) • 81,000 (16%) Manchester residents arrived in the UK between 2001 and 2011, mostly settling in City Centre ward (33% of ward’s current population), its neighbouring wards and Longsight (30% of current population) • Chorlton Park’s population has grown by 26% but only 8% of its residents are immigrants • Gorton South’s population of children aged 0-4 has increased by 87% since 2001 (13% of ward population) followed by Cheetham (70%), Crumpsall (68%), Charlestown (66%) and Moss Side (60%) • Moss Side, Gorton South, Crumpsall and Cheetham have around 25% more 5-15 year olds than in 2001 whereas Miles Platting and Newton Heath, Woodhouse Park, Moston and Withington have around 20-25% fewer. City Centre continues to have very few children in this age group • 18-24 year olds increased by 288% in City Centre since 2001 adding 6,330 residents to the ward. Ardwick, Hulme, Ancoats and Clayton and Bradford have also grown substantially in this age group • Didsbury West has lost 18-24 aged population (-33%) since 2001, followed by Chorlton (-26%) • City Centre working age population has grown by 192% since 2001. -

W. Arthur Lewis and the Dual Economy of Manchester in the 1950S

This is a repository copy of Fighting discrimination: W. Arthur Lewis and the dual economy of Manchester in the 1950s. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/75384/ Monograph: Mosley, P. and Ingham, B. (2013) Fighting discrimination: W. Arthur Lewis and the dual economy of Manchester in the 1950s. Working Paper. Department of Economics, University of Sheffield ISSN 1749-8368 2013006 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Sheffield Economic Research Paper Series SERP Number: 2013006 ISSN 1749-8368 Paul Mosley Barbara Ingham Fighting Discrimination: W. Arthur Lewis and the Dual Economy of Manchester in the 1950s March 2013 Department of Economics University of Sheffield 9 Mappin Street Sheffield S1 4DT United Kingdom www.shef.ac.uk/economics 1 Fighting Discrimination: W. -

Miles Platting, Newton Heath, Moston & City Centre Neighbourhood

Miles Platting, Newton Heath, Moston & City Centre Neighbourhood Health & Social Care Profile Miles Platting, Newton Heath, Moston & City Centre - Health & Social Care Cohort Profile December 2019 Page 1 Introduction to MHCC Neighbourhood & Cohort Profile Reports The Locality Plan developed by Health & Social Care commissioners in Manchester sets an ambition that those sections of the population most at risk of needing care will have access to more proactive care, available in their local communities. The key transformation is the establishment of 12 Integrated Neighbourhood Teams across the City based on geographical area as opposed to organisation. The teams focus on the place and people that they serve, centred around the ethos that ‘The best bed is your own bed’ wherever possible and care should be closer to home rather than delivered within a hospital or care home. The ambition of this model is to place primary care (GP) services at the heart of an integrated neighbourhood model of care in which they are co-located with community teams. These teams could include Community Pharmacists, Allied Health Professionals (AHPs), Community Nursing, Social Care Officers, Intermediate Care teams, Leisure and health promotion teams, Ambulance teams and 3rd sector teams, with a link to educational and employment teams. All services are based upon a 12/3/1 model of provision, where most services should be delivered at the neighbourhood* level (12) unless they require economies of scale at a specialist local level (3), or a single City-wide level -

Manchester Visitor Information What to See and Do in Manchester

Manchester Visitor Information What to see and do in Manchester Manchester is a city waiting to be discovered There is more to Manchester than meets the eye; it’s a city just waiting to be discovered. From superb shopping areas and exciting nightlife to a vibrant history and contrasting vistas, Manchester really has everything. It is a modern city that is Throw into the mix an dynamic, welcoming and impressive range of galleries energetic with stunning and museums (the majority architecture, fascinating of which offer free entry) and museums, award winning visitors are guaranteed to be attractions and a burgeoning stimulated and invigorated. restaurant and bar scene. Manchester has a compact Manchester is a hot-bed of and accessible city centre. cultural activity. From the All areas are within walking thriving and dominant music distance, but if you want scene which gave birth to to save energy, hop onto sons as diverse as Oasis and the Metrolink tram or jump the Halle Orchestra; to one of aboard the free Mettroshuttle the many world class festivals bus. and the rich sporting heritage. We hope you have a wonderful visit. Manchester History Manchester has a unique history and heritage from its early beginnings as the Roman Fort of ‘Mamucium’ [meaning breast-shape hill], to today’s reinvented vibrant and cosmopolitan city. Known as ‘King Cotton’ or ‘Cottonopolis’ during the 19th century, Manchester played a unique part in changing the world for future generations. The cotton and textile industry turned Manchester into the powerhouse of the Industrial Revolution. Leaders of commerce, science and technology, like John Dalton and Richard Arkwright, helped create a vibrant and thriving economy. -

From Manufacturing Industries to a Services Economy: the Emergence of a 'New Manchester' in the Nineteen Sixties

Introductory essay, Making Post-war Manchester: Visions of an Unmade City, May 2016 From Manufacturing Industries to a Services Economy: The Emergence of a ‘New Manchester’ in the Nineteen Sixties Martin Dodge, Department of Geography, University of Manchester Richard Brook, Manchester School of Architecture ‘Manchester is primarily an industrial city; it relies for its prosperity - more perhaps than any other town in the country - on full employment in local industries manufacturing for national and international markets.’ (Rowland Nicholas, 1945, City of Manchester Plan, p.97) ‘Between 1966 and 1972, one in three manual jobs in manufacturing were lost and one quarter of all factories and workshops closed. … Losses in manufacturing employment, however, were accompanied (although not replaced in the same numbers) by a growth in service occupations.’ (Alan Kidd, 2006, Manchester: A History, p.192) Economic Decline, Social Change, Demographic Shifts During the post-war decades Manchester went through the socially painful process of economic restructuring, switching from a labour market based primarily on manufacturing and engineering to one in which services sector employment dominated. While parts of Manchester’s economy were thriving from the late 1950s, having recovered from the deep austerity period after the War, with shipping trade into the docks at Salford buoyant and Trafford Park still a hive of activity, the ineluctable contraction of the cotton industry was a serious threat to the Manchester and regional textile economy. Despite efforts to stem the tide, the textile mills in 1 Manchester and especially in the surrounding satellite towns were closing with knock on effects on associated warehousing and distribution functions. -

Three Policy Priorities for Greater Manchester January 2017

Three policy priorities for Greater Manchester January 2017 Introduction The first metro mayor of Greater Manchester will be elected with a vision for the city and clear strategic, deliverable policies to meet it. The challenge and workload will be considerable, with powers and expectations ranging from delivering policy, to establishing the institutions and capacity for effective city-region governance. This briefing offers three priorities that address the biggest issues facing Greater Manchester. A ‘quick win’ will help the mayor to set the tone for delivery right from the start. Delivering results quickly will build trust, and show what the metro mayor is able to do for the city-region. The best ‘quick wins’ in these circumstances are high profile and of value to citizens. Strategic decisions form the framework for delivering the metro mayor’s vision. As such, the mayor will have the power to take the decisions that will make the most of the new geography of governance. While the mayor will be keen to show progress towards their vision, strategic decisions will often take longer to show outcomes, therefore careful evaluation is needed to allow for flexibility and to demonstrate the effects. A long term vision for the city will be the key election platform – it is what the mayor is working towards while in office. This should be ambitious, but reflect the real needs and potential of the city. Some aspects of the vision will be achievable within the mayor’s term in office, while others will build momentum or signal a change in direction. It is important to be clear and strike the balance of where each policy lies on this spectrum. -

Appendix 2 Automatic Traffic and Cycle Counts

APPENDIX 2 AUTOMATIC TRAFFIC AND CYCLE COUNTS AUTOMATIC TRAFFIC AND CYCLE COUNTS Summary data for the following continuous ATC and ACC sites relevant to Manchester is shown in this Appendix. ATC Data is available in 2008 for: Site Map Location 00301081/2 1 A5103 Princess Road, Hulme 00301151/2 1 A6 Downing Street, Manchester 00301211/2 2 A6010 Alan Turing Way, Philips Park 00302101/2 3 B5167 Palatine Road, West Didsbury 00390111/2 3 A5103 Princess Road, Northenden 00390281/2 2 A665 Great Ancoats Street, Manchester 00390481 1 A34 Oxford Road, Manchester (Nb only) 00390561/2 1 A56 Bridgewater Viaduct/Deansgate, Manchester 00390661/2 1 A56 Chester Road, St. Georges 00690881/2* 1 A6042 Trinity Way, Salford 00390891/2 2 B5117 Wilmslow Road, Rusholme 00391041/2 2 A664 Rochdale Road, Harpurhey Data is unavailable in 2008 for: Site Map Location 00301071/2 1 A5067 Chorlton Road, Hulme 00301121/2 1 A34 Upper Brook Street, Manchester 00301171/2 2 A665 Chancellor Lane, Ardwick 00301201/2 2 A662 Ashton New Road, Bradford ACC Data is available in 2008 for: Site Map Location 00002176 3 Riverside, Northenden 00002177 3 Fallowfield Loop (East), Fallowfield 00002178 1 Sackville Street, Manchester 00002179 2 Danes Road, Rusholme 00030001 3 World Way, Manchester Airport (Cycle Path) 10370160 1 A6 London Road, Manchester (Cycle Path) 10370540 3 Simonsway, Wythenshawe (Cycle Path) 10370550 3 A560 Altrincham Road, Baguley (Cycle Path) 10370560 1 Alexandra Park (Northern Entrance), Moss Side 10370570 2 Stockport Branch Canal, Openshaw (Cycle Path) 10370680 2 Rochdale Canal, Miles Platting 10370690 2 Philips Park, Bradford 10370703 3 Black Path, Portway, Wythenshawe 10370713 3 Black Path, Dinmor Road, Wythenshawe 10370743 1 B5117 Whitworth Park, Oxford Road, Rusholme 10370753 3 Hardy Lane, Chorlton Data is unavailable in 2008 for: Site Map Location 10370473 3 Ford Lane, Didsbury 10370530 3 A5103 Princess Road, Withington 10670600 1 Princes Bridge, Salford For each site the following graphs and tables are given: • A graph showing 24-hour average daily traffic flows in 2008. -

The Base, Manchester

Apartment 108 The Base, Worsley Street, Manchester, M15 4JP Two Bed Apartment Contact: The Base, Manchester t: 0161 710 2010 e: [email protected] or • Well-presented two bedroom apartment [email protected] • Located in the sought after Castlefield area Viewings: of Manchester City Centre Strictly by Appointment • Positioned on the first floor of the Base Landwood Group, South Central Development 11 Peter Street Manchester • Benefitting from two bathrooms, secured M2 5QR parking & balcony Date Particulars — March 2020 • Available with Vacant Possession Tenure Information The premises are held under a long leasehold title for a period of 125 years from 2003, under title number MAN60976. The annual service charge is £2045.76 per annum with the ground rent being £276.52 per annum. Tenancies Available with vacant possession. VAT All figures quoted are exclusive of VAT which may be applicable. Location Legal Each Party will be responsible for their own legal costs. The Base is located in the sought after Castlefield area of Manchester City centre. The area is extremely popular with young professionals and students due to its short Price distance from Manchester City Centre, next door to a £200,000. selection of bars and restaurants and it close proximity to the university buildings. EPC It has excellent road links into and around the city centre EPC rating D. and the Deansgate/Castlefield metrolink station is located approximately 5 minutes’ walk away. Important Notice Landwood Commercial (Manchester) Ltd for