GMPR13 Greengate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

14-1676 Number One First Street

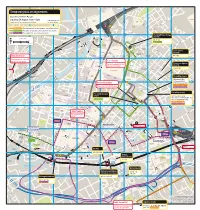

Getting to Number One First Street St Peter’s Square Metrolink Stop T Northbound trams towards Manchester city centre, T S E E K R IL T Ashton-under-Lyne, Bury, Oldham and Rochdale S M Y O R K E Southbound trams towardsL Altrincham, East Didsbury, by public transport T D L E I A E S ST R T J M R T Eccles, Wythenshawe and Manchester Airport O E S R H E L A N T L G D A A Connections may be required P L T E O N N A Y L E S L T for further information visit www.tfgm.com S N R T E BO S O W S T E P E L T R M Additional bus services to destinations Deansgate-Castle field Metrolink Stop T A E T M N I W UL E E R N S BER E E E RY C G N THE AVENUE ST N C R T REE St Mary's N T N T TO T E O S throughout Greater Manchester are A Q A R E E S T P Post RC A K C G W Piccadilly Plaza M S 188 The W C U L E A I S Eastbound trams towards Manchester city centre, G B R N E R RA C N PARKER ST P A Manchester S ZE Office Church N D O C T T NN N I E available from Piccadilly Gardens U E O A Y H P R Y E SE E N O S College R N D T S I T WH N R S C E Ashton-under-Lyne, Bury, Oldham and Rochdale Y P T EP S A STR P U K T T S PEAK EET R Portico Library S C ET E E O E S T ONLY I F Alighting A R T HARDMAN QU LINCOLN SQ N & Gallery A ST R E D EE S Mercure D R ID N C SB T D Y stop only A E E WestboundS trams SQUAREtowards Altrincham, East Didsbury, STR R M EN Premier T EET E Oxford S Road Station E Hotel N T A R I L T E R HARD T E H O T L A MAN S E S T T NationalS ExpressT and otherA coach servicesO AT S Inn A T TRE WD ALBERT R B L G ET R S S H E T E L T Worsley – Eccles – -

The Domesday Record of the Land Between Ribble and Mersey

THE DOMESDAY RECORD OF THE LAND BETWEEN RIBBLK AND MERSEY. By Andrew E. P. Gray, M.A., F.S.A., RECTOR OK V.'AI.I.ASKV. (Read nt December, ,887.) REALLY critical edition of the I.ibfr de IVinloniii las A Domesday Hook is technically called] one which would bring the full resources of modern scholarship to hear upon all the points suggested by it, is still a desideratum, and, as Pro fessor Freeman says, it is an object which ought to be taken up as a national work. A considerable amount of Domesday litera ture has appeared since the royal order in 1767 for the publication of this amongst other records : but much remains to be done, for a great deal of that which has been given to the world on the subject is deficient in breadth of treatment and in accuracy of criticism. We in this part of the country are greatly indebted to Mr. Beamont for his Introduction and Notes to the photozinco- graphic facsimile of the Domesday Record of the two north western counties palatine. Mr. Beamont has been a member of this society almost ever since its foundation 40 years ago, and is one of whom the society is justly proud. It seems, indeed, rash for me to venture upon the subject which I have chosen, lest I should be supposed to be putting myself in competition with him, or setting myself up as a critic upon his Introduction ; but Dt 2 86 The Domesday Record of the I thought that perhaps we might be led over some new ground to-night, if we turned to the Domesday account of the land Inter Ripam et Afers/tani, and considered, firstly, the history of that territory, and then its hundreds, the townships mentioned, the landlords, and the churches. -

Roman Roads of Britain

Roman Roads of Britain A Wikipedia Compilation by Michael A. Linton PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Thu, 04 Jul 2013 02:32:02 UTC Contents Articles Roman roads in Britain 1 Ackling Dyke 9 Akeman Street 10 Cade's Road 11 Dere Street 13 Devil's Causeway 17 Ermin Street 20 Ermine Street 21 Fen Causeway 23 Fosse Way 24 Icknield Street 27 King Street (Roman road) 33 Military Way (Hadrian's Wall) 36 Peddars Way 37 Portway 39 Pye Road 40 Stane Street (Chichester) 41 Stane Street (Colchester) 46 Stanegate 48 Watling Street 51 Via Devana 56 Wade's Causeway 57 References Article Sources and Contributors 59 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 61 Article Licenses License 63 Roman roads in Britain 1 Roman roads in Britain Roman roads, together with Roman aqueducts and the vast standing Roman army, constituted the three most impressive features of the Roman Empire. In Britain, as in their other provinces, the Romans constructed a comprehensive network of paved trunk roads (i.e. surfaced highways) during their nearly four centuries of occupation (43 - 410 AD). This article focuses on the ca. 2,000 mi (3,200 km) of Roman roads in Britain shown on the Ordnance Survey's Map of Roman Britain.[1] This contains the most accurate and up-to-date layout of certain and probable routes that is readily available to the general public. The pre-Roman Britons used mostly unpaved trackways for their communications, including very ancient ones running along elevated ridges of hills, such as the South Downs Way, now a public long-distance footpath. -

The Chapel Street Heritage Trail Queen Victoria, Free Parks, the Beano, Marxism, Heat, Vimto

the Chapel Street heritage trail Queen Victoria, free parks, the Beano, Marxism, Heat, Vimto... ...Oh! and a certain Mr Lowry A self-guided walk along Chapel Street There’s more to Salford than its favourite son and his matchstick men from Blackfriars Bridge to Peel Park. and matchstick cats and dogs. Introduction This walk takes in Chapel Street and the Crescent – the main corridor connecting Salford with Manchester city centre. From Blackfriars Bridge to Salford Museum and Art Gallery should take approximately one and a half hours, with the option of then exploring the gallery and Peel Park afterwards. The terrain is easy going along the road, suitable for wheelchair users and pushchairs. Thanks to all those involved in compiling this Chapel Street heritage trail: Dan Stribling Emma Foster Mike Leber Ann Monaghan Roy Bullock Tourism Marketing team www.industrialpowerhouse.co.uk If you’ve any suggestion for improvements to this walk or if you have any memories, stories or information about the area, then do let us know by emailing [email protected] www.visitsalford.com £1.50 Your journey starts here IN Salford The Trail Background Information Chapel Street was the first street in the United Kingdom to be lit by gas way back in 1806 and was one of the main roads in the country, making up part of the A6 from London to Glasgow. Today it is home to artists’ studios, Salford Museum and Art Gallery, The University of Salford, great pubs and an ever- increasing number of businesses and brand new residences, meaning this historic area has an equally bright future. -

Chapter 4 URBAN REGENERATION CITY of MANCHESTER

Chapter 4 URBAN REGENERATION CITY OF MANCHESTER Table of Contents 4.1 Introduction .............................................................................................................. 4 4.2 Brief History of Manchester: City Profile ........................................................ 4 4.2.1 Post-Industrial Shift ............................................................................................... 4 4.2.2 Greater Manchester Regional Structure................................................................. 5 4.2.3 Creating a Centre: Ongoing Management of Growth in the Manchester Core ..... 5 4.3 Castlefield ................................................................................................................. 7 4.3.1 Background............................................................................................................ 7 4.3.2 Decline of the 1950's and 1960's............................................................................ 8 4.3.3 Regeneration - Urban Heritage Park...................................................................... 8 4.3.4 Key Projects of the Regeneration Programme - Results........................................ 8 4.3.4.1 Redevelopment of the Middle Warehouse (Castle Quay) ......................................................... 8 4.3.4.2 Slate Wharf ................................................................................................................................9 4.3.4.3 Merchants' Warehouse............................................................................................................. -

Frisians in Roman Britain in the Light of the Available Epigraphic Sources

Vol. 4, no. 1/2012 STYLES OF COMMUNICATION Frisians in Roman Britain in the Light of the Available Epigraphic Sources Marcin Buczek, PhD Student University of Wrocław, Poland [email protected] Abstract: The paper discusses the notion of Frisian presence in both the Roman Britain and the Roman army. It investigates the available Latin sources, which provide us with certain amount of information concerning Frisians‟ role, significance and distribution during the period of the Roman ruling. Finally, the author tries, on the basis of the available resources, to draw some conclusions regarding the perception of Frisians by both Romans and Brits. All the analyzed materials are taken from the extensive database of the Roman Inscriptions that are to be found in Britain, which is an invaluable source of knowledge of the military tradition of the Roman Empire and the units serving on the Isles. The paper aims at showing the importance of Frisian participation in both Roman invasion and the Adventus Saxonum. It tries to shed a new light on the perception of not only Frisians but all the Germanic tribes. Keywords: Frisians, Roman Inscriptions in Britain, Roman Britain, Germanic tribes. Place – Britain, a former Roman Province. Time – the second half of the 5th century. Main characters: the “good” ones – innocent inhabitants of Britain, the “bad” ones – barbarian assailants – Saxons, Jutes, Angles. This is a simplified image presented in the majority of the history textbooks that draws on traditional depiction of the Western Roman Empire. That is how the perception of both Britain, as a secondary and relatively insignificant part of the Empire, and Barbarians as savage pillagers or even murderers, is being ingrained in the minds of generations of people. -

Pride Shuttle Services and Bus Departure Points 2019

T EE STR N TIO Y RA A PO G W OR Temporary bus arrangements T C D ITY U RIN A C T 6 IE 6 5 S Manchester Pride Parade, T T R S E E N Sorting Office T IO T Saturday 24 August 11am – 6pm 4 Visit www.tfgm.com A Manchester A 66 5 R Co-op A Arena 6 O Building P Parade starts at 12 noon from Liverpool Road for further details A Victoria R N O C G Station E D L A O ANGEL S R 2 T 4 SQUARE R Victoria 0 E LE T 6 E H Fire Station T A O Shuttlebus 1 Piccadilly (Stop S) to the Aquatics Centre/Oxford Road A D M M H V I C P I L S C L O O T ER R N O Shuttlebus 2 Piccadilly Gardens (Stop P) to Shudehill Interchange NK R A IA B E S S T T A S E N T T U A G T H L R N T L E Shuttlebus 3 Piccadilly (Stop S) to Deansgate station I I E A O New M E E N L T R Century A T S P S House T P R Shudehill Interchange R H A E O N CIS E A B O A V T L G E D C R Tower A N (StandD B) H O C L L I S Y K T N E R A F E G E V T R T Scale 1 : 3700 W E A AT I LG O A Chetham's IL R 2 T N R M 6 O S G School BA A L 36, 37, 38 D L O D O of Music H 0 100 200 yards N A G N N T S O E N V S T O S ER T E O I T L Shuttlebus 2 D R R L RE ST S R T T ET IL E A 0 100 200 metres O S W E O A T A H R D S E A T R CT National D N T U O U D S Football Shudehill H Crowne Plaza IA P Cinema S M V Hotel Museum R Interchange HA Y A CATHEDRAL O I D T L I R GARDENS C O N I O R T Travelshop Holiday Inn T C Manchester I The Printworks Express S V V Cathedral T IC R T E PEL O E Lever Street HA R Corn Exchange T C I W Shudehill A I (Stop EM) T B H Centre for Chinese R Y Contemporary Art T S H T G L O Manchester -

Heywood Notes & Queries

HEYWOOD NOTES & QUERIES. Reprinted fione the "Heywood Advertiser ." CONDUCTED BY J . A. GREEN. VOL. III . No. 25. ,,jFriba1, 3aiuuarp 11th, 1902 . [242.] JOHN KAY TAYLOR . (See Note No. 152 .) Since the publication of the particulars given at No. 152, I have been favoured with the loan of a little book which contains addi- tional information . It is entitled : A New selection of Hymns, compiled for the use of the Chartists, of Great Britain and Ireland . Selected, arranged, and published under the superintendence of a committee ap- pointed by the Chartist Delegates of South Lancashire . Manchester : J . Leach, printer, 40, Oak-street, Swan-street . [ ] 32 me. pp . 1- At this time of day it is difficult to believe that groups of men would unite in singing some of the "hymns" collected in this book . Ii a man is known by the company he keeps then Taylor is found here in very good com- pany indeed . The best hymns are by Burns, Campbell, Ebenez .r Elliott, Thomas Cooper, 2 and Robert Nicoll . The contributions of J. K. Taylor are not the worst in the book, but the following samples of his quality will suffice : - Hymn, 3-page 5 . Chartist Hymn (S.M.). 1 What can withstand the power, When Britain's sons unite, Throughout this empire in one hour, For to assert their right. (4 stanzas, signed J. K. Taylor, Heywood.) Hymn, 14-page 18. Chartists' Hymn (P.M.). 1 Come join the patriot's host, The contest now begun, Let each and all maintain his post And labour's battle's won. -

II. on the ROMAN STATION, CONDATE. by J. Robson, Esq., Warrinyton

34 were about four inches deep and three in diameter. Each contained n quantity of black ashes intermixed with charcoal. One had a sort of pinched ornament running round the neck. Dr. Kendrick said that some of the bones must have been those of a large man. About three quarters of a mile further on, and in a direct line, the road re-appears at a point called Stretton New Barn; and half a mile further, near Mr. Okell's, in the Big Town Field of Stretton. How it reaches Stretton New Barn from the point near which the urns were found, is as yet undecided. Some think it was continued in a straight line to the westward of Stretton Church; but others maintain that it made a detour in the interval, crossing Pewter Spear Lane and passing over a bed of gravel, to avoid a series of undrained and low lying fields. Here we leave the subject for the present; but on some future occasion it may be our pleasing duty to lay before the Society a record of further discoveries, either at Wilderspool or in continua tion of the Roman road. II. ON THE ROMAN STATION, CONDATE. By J. Robson, Esq., Warrinyton. The difficulties and doubts which have beset all attempts to make out the course of the Tenth Iter of Antonine, are by no means encouraging for a new essay; but perhaps the discoveries now laid before the Society will help us on a little in the inquiry. In Antonine's Second Iter, we find a route from York to Chester, the part of which immediately connected with this neighbourhood runs thus: Mamucio............................. -

The Condition of the Working-Class In

THE CONDITION OF THE WORKING-CLASS IN ENGLAND insr 18-44 WITH PREFACE WRITTEN IN 1892 FREDERICK ENGELS TRANSLATED BY FLORENCE KELLEY WISCHNEWETZKY LONDON: GEORGE ALLEN & UNWIN LTD. RUSKIN HOUSE 40 MUSEUM STREET, W.C.i +- m f TABLE OF CONTENTS. _ TAGS v—xix ^ "^"Preface Introduction .......» • 1 CHAPTER I. - • The Industrial Proletariat • •« 19 CHAPTER II. The Great Towns ...... 23 CHAPTER III. Competition ..--...75 CHAPTER IV. * Immigration Irish ...... 90 CHAPTER V. Results ....... 95 CHAPTER VI. Single Branches of Industry— Factory Hands - 134 CHAPTER VLJ. The Remaining Branches of Industry • • 188 CHAPTER VIII. "* Labour Movements - - - • - 212 CHAPTER IX. Mining The Proletariat ----- 241 CHAPTER X. Agricultural • - The Proletariat t -261 CHAPTER XI. Attitude of the Bourgeoisie towards the Proletariat 276 Translator's Note ------ 299 The Great Towns. 23 THE GREAT TOWNS. A town, such as London, where a man may wander for hours to gether without reaching the beginning of the end, without meeting the slightest hint which could lead to the inference that there is open country within reach, is a strange thing. This colossal centralisation, this heaping together of two and a half millions of human beings at one point, has multiplied the power of this two and a half millions a hundredfold ; has raised London to the commercial capital of the world, created the giant docks and assembled the thousand vessels that continually cover the Thames. I know nothing more imposing than the view which the Thames offers during the ascent from the sea to -

Lancashire: a Chronology of Flash Flooding

LANCASHIRE: A CHRONOLOGY OF FLASH FLOODING Introduction The past focus on the history of flooding has been mainly with respect to flooding from the overflow of rivers and with respect to the peak level that these floods have achieved. The Chronology of British Hydrological Events provides a reasonably comprehensive record of such events throughout Great Britain. Over the last 60 years the river gauging network provides a detailed record of the occurrence of river flows and peak levels and flows are summaried in HiflowsUK. However there has been recent recognition that much flooding of property occurs from surface water flooding, often far from rivers. Locally intense rainfall causes severe flooding of property and land as water concentrates and finds pathways along roads and depressions in the landscape. In addition, intense rainfall can also cause rapid rise in level and discharge in rivers causing a danger to the public even though the associated peak level is not critical. In extreme cases rapid rise in river level may be manifested as a ‘wall of water’ with near instantaneous rise in level of a metre or more. Such events are usually convective and may be accompanied by destructive hail or cause severe erosion of hillsides and agricultural land. There have been no previous compilations of historical records of such ‘flash floods’or even of more recent occurrences. It is therefore difficult to judge whether a recent event is unusual or even unique in terms of the level reached at a particular location or more broadly of regional severity. This chronology of flash floods is provided in order to enable comparisons to be made between recent and historical floods, to judge rarity and from a practical point of view to assess the adequacy of urban drainage networks. -

Chapter II Normans and Plantagenets

Chapter Two NORMANS AND PLANTAGENETS : 1086-1485 THE DOMESDAY BOOK . OCHDALE'S written history begins in 1086, when William the Conqueror sent his men all over England to find out how much land was being cultivated and how much revenue he might expect R to collect : the result was the Domesday (or Doomsday) Book, so called because of its uncompromising thoroughness and detail . Its two volumes, written in crabbed Latin, with words occasionally scored through in red for emphasis, instead of being underlined, are now displayed at the Public Record Office, London . One can imagine the difficulties of the Norman inspectors : how unwillingly and in what various dialects the English land-holders gave their answers when the " day of reckoning " came upon them . Perhaps this may account for the fact that "Rochdale" is set down as " Recedham ." It was probably then, as we still hear it today, pro- rounced as " Ratchda ' " with a long " a," and a soft Cheshire " c." Very freely translated and abbreviated, this is the gist of the Domesday entry concerning Rochdale as it was in the time of Edward the Confessor (1042-1066), excluding such details as the King's personal property and lands in the Salford Hundred : King Edward held Salford . To this Hundred belonged 21 manors held by as many thanes ; in which there were 112 hides and 102 carucates of land . Camel, a tenant of 2 of these hides in Recedham, was free of all customs but these six : theft, housebreaking, premeditated assault, breach of the peace, not answering the reeve's summons, and 1 4 ROCHDALE RETROSPECT continuing a fight after swearing on oath to desist .