Youngstown 2010′

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2009 Annual Report Restoration Project Was Undertaken in an Area of the Preserve That Had Been Highly Impacted by Sod and Crop Farming

Mill Creek Preserve The Mill Creek Preserve boasts a variety of upland and wetland habitats, most notably, a regionally significant 102-acre forested Mill Creek MetroParks wetland complex. In 2009, a large wetland 2009 Annual Report restoration project was undertaken in an area of the Preserve that had been highly impacted by sod and crop farming. The project restored wetland functions and habitats to the Mill Creek floodplain and provided a buffer to the existing forested wetlands. Invasive plant species were removed and native species were planted. In time, visitors will be able to walk through the restoration area on elevated terraces and observe the various wetland habitats and the wildlife using them. The MetroParks acquired 100% funding through a grant for this wetland restoration project. Director's Report Each and every year since 1891, Mill Creek MetroParks has changed and grown. The year 2009 was no exception. History was made this year when the Board of Park Commissioners passed a resolution requesting that Probate Court Judge Mark Belinky, the appointing authority of the board, increase the number of commissioners from three to five. This resolution, in accordance with the Ohio Revised Code, was passed at the October board meeting. The new appointments were scheduled to take place in early January 2010. Another major change that impacted the MetroParks this past year was the resignation of the Executive Director on August 31. Tom Bresko, Director of Recreation, was appointed Interim Director immediately, and assumed his duties September 1. Attorney Carl Nunziato, who served on the MetroParks Board of Commissioners from 2003 to 2009, retired as a Board member effective December 31. -

NYO-Property-Group-Resume.Pdf

PROPERTY MANAGEMENT RESUME ABOUT NYO PROPERTY GROUP Our history. Our commitment. Our future. In 2010, Dominic J. Marchionda, a local developer As the two entities began to hear and learn raised in Youngstown, Ohio announced the opening more about each other, they realized their of a student housing project, the Flats at Wick, in visions for the City of Youngstown and their the heart of Youngstown State University (YSU). respective development plans were aligned. With each entity owning a significant share During this project, Dominic spent a great deal of of downtown real estate in close proximity time in and around the downtown and campus of each other, they began to understand the areas where he would recognize the once value for their businesses and the community prominent buildings that towered over him as a in collaboration versus competition. Soon young boy shopping with his mother on Saturday thereafter, a partnership was struck, forming afternoons, now sitting vacant and unattended. NYO Property Group. NYO stands This project led to the acquisition of three buildings for New York (NY) and Youngstown (YO) for a in the City Center: The Erie Terminal Building, Wick new Youngstown. Tower and Legal Arts Building. While the partnership understands the In 2011, Pan Brothers Associates, a real estate importance in preserving the industrial heritage investment firm led by three brothers out of New of Youngstown, they are both committed York, NY, and owners of several prominent and to revitalizing their inventory of historic historical commercial buildings in the downtown and prominent structures to help catalyze business district had begun to initiate a reinvestment and further development development plan for their real estate holdings in downtown Youngstown, Ohio. -

Studentexperiencefall2019cale

SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY 1 2 3 SA - - BuildTHURSDAY,A AUGUSTPenguin 21 where and when? Follow @ysu_activities on social media for location & time. Co-Sponsor: Student Government Association 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 GET THE YSU APP! EVENTS,NEWS, SERVICES, COURSES, MAPS, MEET STUDENTS & CLASSMATES OPENING AUGUST 19, IN THE HUB GET IT ON GOOGLE PLAY HOURS 10:30A–3P MONDAY THROUGH FRIDAY OR THE APP STORE. The Melt Lab brings the delicious, comforting flavors of the perfect sandwich—grilled cheese! 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 CR Fall Hours Begin at the SA IGNITE CR SPINNING Certification Rec Center 1–8:30p | WATTS This comprehensive workshop will See www.ysu.edu/reccenter First year students will spend the give you all the tools you need day getting to know faculty, staff, to become a certified SPINNING H First Year Student and each other in preparation for instructor. ARE YOU Move-In the year ahead. Co-Sponsor: First 8a–5p | Aerobics Studio, Rec Center #HEREFORIT? 8a–4p | Residence Halls Year Student Services Co-Sponsor: Mad Dogg SPINNING Welcome Week has been organized H Welcome Bash SA Spirit Session SA Class Find Tours 8p | Stambaugh Stadium Bring your class schedule for a door- to help you become familiar with 7:30–10p | Heritage Park Co-Sponsor: Student Activities, Rec We’re kicking off the semester to-door tour. campus, meet other students & Center with some YSU spirit and we want 9a–2p | Chestnut Room, Kilcawley connect you with resources you’ll need all students to join us! Come to Center Co-Sponsor: First Year Student for a successful career at YSU! See a full FOR the stadium in your best YSU gear Services schedule at ysu.edu/welcomeweek. -

Federal Building United States Courthouse in Youngstown, Ohio, Was Designed and Constructed Under the U

FEDERAL BUILDING UNITED STATES COURTHOUSE FEDERAL BUILDING UNITED STATES COURTHOUSE Youngstown, Ohio Youngstown, Ohio The Federal Building United States Courthouse in Youngstown, Ohio, was designed and constructed under the U.S. General Services Administration’s Design Excellence Program, an initiative to create and preserve a legacy of outstanding public buildings that will be used and enjoyed now and by future generations of Americans. Special thanks to the Honorable William T. Bodoh, Chief Bankruptcy Judge, U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Ohio, for his commitment and dedication to a building of outstanding quality that is a tribute to the role of the judiciary in our democratic society and worthy U.S. General Services Administration U.S. General Services Administration of the American people. Public Buildings Service Office of the Chief Architect Center for Design Excellence and the Arts October 2002 1800 F Street, NW Washington, DC 20405 2025011888 FEDERAL BUILDING UNITED STATES COURTHOUSE FEDERAL BUILDING UNITED STATES COURTHOUSE Youngstown, Ohio Youngstown, Ohio The Federal Building United States Courthouse in Youngstown, Ohio, was designed and constructed under the U.S. General Services Administration’s Design Excellence Program, an initiative to create and preserve a legacy of outstanding public buildings that will be used and enjoyed now and by future generations of Americans. Special thanks to the Honorable William T. Bodoh, Chief Bankruptcy Judge, U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Ohio, for his commitment and dedication to a building of outstanding quality that is a tribute to the role of the judiciary in our democratic society and worthy U.S. -

Popular Annual Financial Report Ended December 31, 2018 Mahoning County, Ohio

Popular Annual Financial Report Ended December 31, 2018 Mahoning County, Ohio Ralph T. Meacham, CPA Mahoning County Auditor Table of Contents Page To the Citizens of Mahoning County ...................................................................................................................................... 2 Mahoning County ......................................................................................................................................................................... 3 County Auditor Organizational Chart .................................................................................................................................... 4 Auditor’s Office .............................................................................................................................................................................. 5 Industry, Commerce and Economic Development ................................................................................................................ 7 Local Government Developments ............................................................................................................................................. 11 Mahoning County – A great place to live, work and play! ................................................................................................. 12 Elected Officials ........................................................................................................................................................................... 15 Economic -

YCSD Newsletter2c

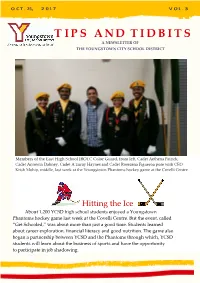

O C T . 25, 2 0 1 7 V O L . 3 T I P S A N D T I D B I T S A NEWSLETTER OF THE YOUNGSTOWN CITY SCHOOL DISTRICT Members of the East High School JROTC Color Guard, from left, Cadet Aethena Patrick, Cadet Antowin Dabney, Cadet A’zuray Haynes and Cadet Rosezena Figueroa pose with CEO Krish Mohip, middle, last week at the Youngstown Phantoms hockey game at the Covelli Centre. Hitting the Ice About 1,200 YCSD high school students enjoyed a Youngstown Phantoms hockey game last week at the Covelli Centre. But the event, called “Get Schooled,” was about more than just a good time. Students learned about career exploration, financial literacy and good nutrition. The game also began a partnership between YCSD and the Phantoms through which, YCSD students will learn about the business of sports and have the opportunity to participate in job shadowing. O C T. 25, 2 0 1 7 V O L . 3 We’re Listening, Responding The Youngstown City School District is offering a new way for parents and community members to communicate their concerns. Callers can dial 330-744-8868 to report issues or complaints. A district representative will answer and input the information into Let’s Talk, a customer service tool that enables CEO Krish Mohip to ensure parents’ questions and concerns are being addressed. “The Youngstown City School District is a public entity and it’s important that we recognize that our families -- and community members in general -- are our customers,” Mohip said. -

Austintown Local School District Mahoning County, Ohio

AUSTINTOWN LOCAL SCHOOL DISTRICT MAHONING COUNTY, OHIO Austintown Middle School COMPREHENSIVE ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDED JUNE 30, 2020 THIS PAGE IS INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK COMPREHENSIVE ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT OF THE AUSTINTOWN LOCAL SCHOOL DISTRICT FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDED JUNE 30, 2020 PREPARED BY TREASURER'S DEPARTMENT BLAISE KARLOVIC, TREASURER/CFO 700 S. RACCOON ROAD AUSTINTOWN, OHIO 44515 THIS PAGE IS INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK AUSTINTOWN LOCAL SCHOOL DISTRICT MAHONING COUNTY, OHIO COMPREHENSIVE ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDED JUNE 30, 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS TITLE PAGE TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................................................................... i-iv I. INTRODUCTORY SECTION Letter of Transmittal ............................................................................................................................ 1-5 List of Principal Officers ..................................................................................................................... 6 Organizational Chart - Operational ...................................................................................................... 7 Organizational Chart - Instructional .................................................................................................... 8 Government Finance Officers Association Certificate of Achievement for Excellence in Financial Reporting ...................................................................................................... -

Youngstown State University Oral History Program

YOUNGSTOWN STATE UNIVERSITY ORAL HISTORY PROGRAM Westlake Terrace Project Resident of Youngstown O. H. 667 DAN EAKINS Interviewed by Joseph Drobney on October 19, 1985 DANIEL EAKINS Dan Eakins was born on January 16, 1915 in Windber, Pennsylvania. Mr. Eakins, who was one of four children, moved to the Youngstown area with his family during the early 1920's. He left school after the eighth grade and entered the work force in Youngstown. During the late 1930's and early 1940's, Dan Eakins worked for a variety of employers in the Youngstown area. He was an employee of the Atlas Powder Company of Ravenna, Ohio, which produced armaments for the u.S. military forces during the Second World War. Also during World War II, Mr. Eakins and his wife (he is now divorced) lived in the government funded Westlake Terrace Housing Project. After World War II, Dan Eakins again held a variety of jobs. He lived, for a short time, outside the state of Ohio. Mr. Eakins is now retired, and lives in a Youngstown Metropolitan Housing Authority apartment complex on the city's east side. O. H. 667 YOUNGSTOWN STATE UNIVERSITY ORAL HISTORY PROGRAM Westlake Terrace Project INTERVIEWEE: DAN EAKINS INTERVIEWER: Joseph Drobney SUBJECT: World War II, Ravenna Arms Plant, Youngstown 1930's - 1940's DATE: October 19, 1985 D: This is an interview with Dan Eakins for the Youngstown State University Oral History Program, on Westlake Terrace, by Joe Drobney, on October 19, 1985, at 1400 Springdale Avenue, Apartment 424, in Youngstown, at approximately 10:00 in the morning. -

20 Federal Place the CITY of YOU

INVESTOR PROSPECTUS YOUNGSTOWN OHIO 20 Federal Place THE CITY OF YOU The one thing that has defined Youngstown throughout its history is its strong entrepreneurial spirit. Anything is possible in Youngstown. BIG and BOLD things are happening everyday in Youngstown. This isn’t your average Rust Belt city. This is the City of You. “A city where anyone can build a future for themselves.” Mayor Jamael Tito Brown – City of Youngstown Website CONTENTS 1 YOUNGSTOWN CONTEXT 5 INCENTIVE POTENTIAL 2 YOUNGSTOWN MOMENTUM 6 MODEL 3 20 FEDERAL PLACE 7 ADDENDUM 4 REINVENTION AT 20 FEDERAL Click on the title to jump to the section 1 YOUNGSTOWN CONTEXT Named “Top 10 Cities to Start a Business” Entrepreneur Magazine YOUNGSTOWN MSA* KEY INDICATORS 545,175 225,604 18,695 Population Households Total Businesses 44.9 $119,046 2.27 Median Age Median Home Value Downtown** Daytime Population/ Downtown Resident Ratio MEGAPOLITAN CITY Youngstown – Center of the YOUNGSTOWN AT THE CENTER “Tech Belt” Megapolitan Megapolitans in the U.S. are clustered networks of 2M+ American cities where the population is projected People to be between 7 and 63 million by 2025.* CLEVELAND 550K 7 MILLION People People live within 75-Miles 700K+ People Extraordinary Teleworking 45 MILES YOUNGSTOWN 228,117 Opportunities Businesses within 75-Miles AKRON MIDWAY Between Cleveland and Pittsburgh (60 Miles) Between Chicago and New York (400 Miles) 2.3M+ People One Day Drive 60% of the U.S. Population PITTSBURGH MSA POPULATION NUMBERS Age Groups & Generations* 19.7% 21.1% 19.3% 26.1% 9.9% Gen Z Millennial Generation X Baby Boomer Greatest Gen. -

Lordstown Motors Sets High Benchmark 2Nd Procurement Event Held Tuesday in Youngstown

Visit us online Poland Union students Plant-based pork to hit www. vindy find their calm, A5 international tables, B8 .com An edition of the Tribune 75¢ Chronicle © 2020 Wednesday February 5, 2020 Lordstown Motors sets high benchmark 2nd procurement event held Tuesday in Youngstown By RON SELAK JR. Staff report YOUNGSTOWN — Lordstown Motors Corp.’s battery-powered Endurance pickup is more akin to the Chevrolet Silverado, but the benchmark the electric vehicle com - pany is trying to achieve for the fleet-style truck is Ford’s F-150. The F-150 is the leader in the fleet market, said John LaFleur, chief operat - ing officer for Lord - stown Motors, which has the objective to “be Staff photos / R. Michael Semple as good or better in all areas” than its com - A large group of supplier representatives attends a meeting hosted Youngstown. The company continues to ready itself to start produc- LaFleur petitor. by Lordstown Motors Corp. on Tuesday in Stambaugh Auditorium, tion of the battery-powered Endurance pickup this year in Lordstown. “I don’t want to dis - count the Silverado because our vehicle is more in line with a Sil - verado than an F-150. We kind of Endurance details modeled it (the Endurance) around that because, you know, the GM (General Motors) plant, GM’s poten - tial partnership with parts that could be there; that’s not finalized yet, but we want to prepare our - selves ... but they (Ford) Inside are the big Area senators work player and to encourage elec - they are the tric-vehicle pur - bench - chases in Ohio. -

Downtown Youngstown Dining Parking 1 Café Cimmento a Ampco Lot, W

Downtown Youngstown Dining Parking 1 Café Cimmento A Ampco Lot, W. Boardman St. 2 Charlie Staples BBQ (designated OH WOW! parking) 3 Cassese’s MVR B Ampco Lot, W. Boardman St. 4 Overture (inside DeYor) C Ampco Lot, W. Front St. 5 V2 Trattoria and Wine Bar D Parking Lot, Freeman Alley 6 Winslow’s Café - Butler Art Institute E Covelli Centre Parking 7 O’Donold’s F Plaza Parking Deck 8 The Lemon Grove Café G Stambaugh Parking Deck 9 Roberto’s Italian Ristorante H USA Lot, E. Commerce St. 10 Joe Maxx Coffee Co. J Ampco Lot, W. Commerce St. 11 Downtown Draught House K Ampco Lot, W. Commerce St. 12 Downtown Circle Deli L Ampco Lot, W. Federal St. 13 End of the Tunnel M Ampco Lot, E. Wood St. 14 Garden Café (inside Davis Center) N YSU Stadium Parking, 5th Ave. 15 Federal Place Food Court: Capitol Grill Saigon Star Café Notes: Magic Mocha Café Subway Street parking is available on Federal Street Pizza Joe’s Yogurt Corner (free or 1-hour metered). 16 Touch the Moon Candy Saloon Many lots offer free parking on weekends. 17 Mahoning Snacks 18 Jorgine’s Deli (inside YMCA) 19 Dooney’s Downtown Grille YSU Campus Area: 20 Subway 21 Inner Circle Pizza 22 University Pizzeria 23 Our Family 24 Jimmy John’s 25 Belleria Pizza Gourmet Sandwiches 26 McDonald’s 27 Taco Bell Attractions 1 OH WOW! The Roger & Gloria Jones Children’s Center for Science & Technology 2 Arms Family Museum 3 Butler Institute of American Art 4 Mahoning County Courthouse 5 McDonough Museum of Art 6 Youngstown Historical Center of Industry and Labor 7 YSU Ward Beecher Planetarium 8 Fellows -

Youngstown Commercial Corridor Study

A MARKET ANALYSIS OF: COMMERCIAL CORRIDORS IN YOUNGSTOWN, OHIO A MARKET ANALYSIS OF: COMMERCIAL CORRIDORS IN YOUNGSTOWN, OHIO Report Date: April 5, 2019 Prepared For: Ian Beniston Executive Director Youngstown Neighborhood Development Corporation 820 Canfield Road Youngstown, OH 44511 Prepared By: Novogradac and Company LLP 1100 Superior Avenue, Suite 900 Cleveland, OH 44114 216-298-9000 April 5, 2019 Ian Beniston Executive Director Youngstown Neighborhood Development Corporation 820 Canfield Road Youngstown, OH 44511 Re: Commercial Corridor Market Analysis for Youngstown, Ohio Dear Mr. Beniston: At your request, Novogradac & Company LLP has performed a commercial corridor market analysis in Youngstown, Ohio. The following report provides support for the findings of the study and outlines the sources of information and the methodologies used to arrive at our conclusions. The scope of this report meets the requirements of Youngstown Neighborhood Development Corporation, including the following: ° Identify areas of focus for future development and redevelopment opportunities. ° Investigating the general economic health and conditions of nine commercial corridors within Youngstown, Ohio with discussion and analysis of employment trends, population trends, employment trends, crime statistics, and average daily traffic counts. ° Reviewing relevant public records and contacting appropriate public agencies and market participants regarding potential commercial and retail demand, including the Chamber of Commerce, Economic Development Department, and real estate professionals. ° Research and analysis of lease listings and executed leases for various commercial corridors, and conclude to achievable lease rates for various corridors. ° Establishing the Subject’s Primary and Secondary Market Area. ° Surveying and photographing commercial corridors, which includes non-commercial uses, to assess the condition of properties along the corridor and current vacancy levels.