America's Missions: the Home Missions Movement and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shakers and Jerkers: Letters from the "Long Walk," 1805, Part I Douglas L

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Religious Studies Faculty Publications Religious Studies 2017 Shakers and Jerkers: Letters from the "Long Walk," 1805, Part I Douglas L. Winiarski University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.richmond.edu/religiousstudies-faculty- publications Part of the Christianity Commons, and the New Religious Movements Commons Recommended Citation Winiarski, Douglas L. "Shakers and Jerkers: Letters from the "Long Walk," 1805, Part I." Journal of East Tennessee History 89 (2017): 90-110. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Religious Studies at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religious Studies Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Shakers and Jerkers: Letters from the “Long Walk,” 1805, Part 1 By Douglas L. Winiarski*a Reports of a bizarre new religious phenomenon made their way over the mountains from Tennessee during the summer and fall of 1804. For several years, readers in the eastern states had been eagerly consuming news of the Great Revival, the powerful succession of Presbyterian sacramental festivals and Methodist camp meetings that played a formative role in the development of the southern Bible Belt and the emergence of early American evangelicalism. Letters from the frontier frequently included vivid descriptions of the so-called “falling exercise,” in which the bodies of revival converts crumpled to the ground during powerful sermon performances on the terrors of hell. But an article that appeared in the Virginia Argus on October 24, 1804, announced the sudden emergence of a deeply troubling new form of convulsive somatic distress. -

September 2017

JOURNEY A Communicator for the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Kingston September 2017 www.romancatholic.kingston.on.ca Happy Anniversaries, Archbishop O’Brien! On Sunday, July 30th, Archbishop Brendan O’Brien celebrated two special anniversaries — thirty years as a bishop and ten years as Archbishop of Kingston — with a Mass and garden party at St. Mary’s Cathedral. Several members of his family travelled from Ottawa and Montreal to join the Archbishop for this special event, including (pictured above, from left to right), his brother, Michael O’Brien, his sister-in-law, Marie O’Bri- en, his sister, Rosemary O’Brien, his brother-in-law, Randal Marlin, his sister, Elaine Marlin, and his broth- er, Gregory O’Brien. Full story and more pictures on page 2 and page 3. photo by Katherine Quinlan JOURNEY Page 2 September 2017 A Reflection on Milestones Archbishop Brendan M. O’Brien It is often said that it is important to celebrate the milestones of life, whether they be birthdays, wedding anniversaries, graduations, retirements, or other special events. Milestones call our attention to life as a journey. Gathering with family and friends to celebrate a birthday or an anniversary, as many did last month to mark Canada’s 150th birthday, is a time to look back over the intervening years and to give thanks for our blessings as we face the challenges of the future. In my own family, this summer brought a succession of milestones, beginning with my mother’s 100th birthday on June 22nd. She is a healthy, active centenarian, and we gathered in Ottawa for two lively celebrations of her big birthday. -

A Five Minute History of Oklahoma

Chronicles of Oklahoma Volume 13, No. 4 December, 1935 Five Minute History of Oklahoma Patrick J. Hurley 373 Address in Commemoration of Wiley Post before the Oklahoma State Society of Washington D. C. Paul A. Walker 376 Oklahoma's School Endowment D. W. P. 381 Judge Charles Bismark Ames D. A. Richardson 391 Augusta Robertson Moore: A Sketch of Her Life and Times Carolyn Thomas Foreman 399 Chief John Ross John Bartlett Meserve 421 Captain David L. Payne D. W. P. 438 Oklahoma's First Court Grant Foreman 457 An Unusual Antiquity in Pontotoc County H. R. Antle 470 Oklahoma History Quilt D. W. P. 472 Some Fragments of Oklahoma History 481 Notes 485 Minutes 489 Necrology 494 A FIVE MINUTE HISTORY OF OKLAHOMA By Patrick J. Hurley, former Secretary of War. From a Radio Address Delivered November 14, 1935. Page 373 The State of Oklahoma was admitted to the Union 28 years ago. Spaniards led by Coronado traversed what is now the State of Oklahoma 67 years before the first English settlement in Virginia and 79 years before the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth Rock. All of the land now in Oklahoma except a little strip known as the panhandle was acquired by the United States from France in the Louisiana Purchase. Early in the nineteenth century the United States moved the five civilized tribes, the Cherokees, Creeks, Choctaws, Chickasaws, and Seminoles, from southeastern states to lands west of the Mississippi River, the title to which was transferred to the tribes in exchange for part of their lands in the East. -

Ministry Council Periodic External Review Report

Ministry Council Periodic External Review Report The College of the Resurrection, Mirfield November 2015– March 2016 Ministry Division Church House Great Smith Street London SW1P 3AZ Tel: 020 7898 1412 Fax: 020 7898 1421 Published 2016 by the Ministry Division of the Archbishops’ Council Copyright © The Archbishops’ Council 2016 CONTENTS GLOSSARY ....................................................................................................................................1 LIST OF REVIEWERS ..................................................................................................................2 THE PERIODIC EXTERNAL REVIEW FRAMEWORK ...........................................................3 SUMMARY ......................................................................................................................................4 FULL REPORT ..............................................................................................................................7 SECTION ONE: AIMS AND KEY RELATIONS ....................................................................9 A Aims and objectives .......................................................................................................9 B Relationships with other institutions ......................................................................... 11 SECTION TWO: CURRICULUM FOR FORMATION AND EDUCATION ..................... 14 C Curriculum for formation and education.............................................................. 14 SECTION THREE: MINISTERIAL -

The Missionary Work of Samuel A. Worcester

THE MISSIONARY WORK OF SAMUEL A. WORCESTER AMONG THE CHEROKEE: 1825-1840 APPROVED: Major Professor r Professor ^.tf^Tector of the Department of History Dean of the Graduate School THE MISSIONARY WORK OF SAMUEL A. WORCESTER AMONG THE CHEROKEE: 1825-1840 THESIS Presented, to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Jerran Burris White, B.A, Denton, Texas August, 19 70 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS iv Chapters I. AMERICAN BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS FOR FOREIGN MISSIONS AND THE CHEROKEE 1 II. SAMUEL A. WORCESTER--THE CHEROKEE MESSENGER 21 III. WORCESTER V. THE STATE OF GEORGIA 37 IV. WORCESTER*S MISSIONARY ACTIVITIES DURING REMOVAL 68 V. ACCOMPLISHMENTS OF THE CHEROKEE MESSENGER. ... 90 APPENDIX 95 A. CHEROKEE POPULATION STATISTICS B. ILLUSTRATIONS BIBLIOGRAPHY ......... .102 Hi LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure Page 1. The Cherokee Nation in.the East: 1835. ..... 97 2. The Cherokee Alphabet 9 8 3. Cherokee Phoenix. ......99 4. Cherokee Nation in the West: 1840. ...... .100 5. Cherokee Almanac 101 IV CHAPTER I AMERICAN BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS FOR FOREIGN MISSIONS AND THE CHEROKEE The early years of the nineteenth centuty were dynamic, exciting years for the United States. The population was quickly expanding into the trans-Appalachian Westj the nation was firmly establishing itself as an independent country and a world force; increasingly the national philos- ophy became the idea that the nation had a divine origin, a divine inspiration, and a divine authority over the North American continent and any other area of the world to which it might expand.* The nation still reflected the thought of its early settlers, especially the Puritans of New England, There were fears among these people that the deistic-Unitarian influences of the late eighteenth century might corrupt the foundations of religion. -

DICTIONAEY of ALABAMA BIOGRAPHY of Co

600 DICTIONAEY OF ALABAMA BIOGRAPHY of Co. E, Cobb's Georgia legion of cavalry; ter of Scotch. Her maternal grandfather was served through the war; surrendering at a colonel in the Revolutionary Army. Chil- Greensboro, N. C., 1865. He farmed and mer- dren: 1. Laura Amelia, m. Rev. M. Kirkpatrick, chandised, removing for a while to Mississippi. Memphis, Tenn.; 2. Harriett Cooper, m. W. M. In 1882 he located in Anniston and engaged in Jones, Talladega; 3. John Harris, deceased; the real estate business, changing to the lum- 4. William Clark Coolidge, m. Marget E. ber business in 1885, and in 1888 he was elected Flow, Barium Springs, N. C.; 5. Gurdon Robin- mayor of Anniston. He is a Mason and a son, m. Irene Burt, Talladega; 6. Margaret Methodist. Married: August 10, 1885, to Emma, Holman, deceased; 7. Alfred Slaughter, m. Elise daughter of Major T. D. Evans. Children: 1. Whitner, Sanford, Fla.; 8. Theron Rice, de- Minnie G.; 2. Mattie B.; 3. Thomas W.; 4. ceased; 9. James Hazen, New Orleans. Last Jennie J.; 5. Emmet E.; 6. Ella May. Resi- residence: Tuskegee. dence: Tarsus, near Anniston. FOSTER, HARDY, planter, was born May FOSTER, GEORGE W., physician, was born 29, 1792, in Columbia County, Ga., and died December 19, 1856, in Jackson County; son August 18, 1848, at Foster's, Tuscaloosa County; of T. Boyd and Sarah Mumford (Mason) Fos- son of John and Elizabeth (Savidge) Foster ter, of Virginia, the former a civil engineer of Georgia; grandson of Arthur and Martha and surveyor of Jackson County for forty years. -

Chapter 4: Jehovah's Witnesses

In presenting this dissertation/thesis as a partial fulfillment of the requirements for an advanced degree from Emory University, I agree that the Library of the University shall make it available for inspection and circulation in accordance with its regulations governing materials of this type. I agree that permission to copy from, or to publish, this thesis/dissertation may be granted by the professor under whose direction it was written when such copying or publication is solely for scholarly purposes and does not involve potential financial gain. In the absence of the professor, the dean of the Graduate School may grant permission. It is understood that any copying from, or publication of, this thesis/dissertation which involves potential financial gain will not be allowed without written permission. Student’s signature __________________ Andrea D. Green Moral and Faith Development in Fundamentalist Communities: Lessons Learned in Five New Religious Movements By Andrea D. Green Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Division of Religion ___________________________ John Snarey, Ed.D. Adviser ___________________________ Mary Elizabeth Moore, Ph.D. Committee Member ___________________________ Theodore Brelsford, Ph.D. Committee Member Accepted: ___________________________ Lisa A. Tedesco, Ph.D. Dean of the Graduate School ___________________________ Date Moral and Faith Development in Fundamentalist Communities: Lessons Learned in Five New Religious Movements By Andrea D. Green B.S., Centre College M.Div., Duke University Th.M., Duke University Adviser: John Snarey, Ed.D. An Abstract of A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Emory University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Division of Religion 2008 Abstract “Faith and Moral Development in Fundamentalist Religious Communities: Lessons Learned from Five New Religious Movements” is, first, a work of practical theology. -

A Christian Nation: How Christianity United the People of the Cherokee Nation

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations and Theses City College of New York 2015 A Christian Nation: How Christianity united the people of the Cherokee Nation Mary Brown CUNY City College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cc_etds_theses/372 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] A Christian Nation: How Christianity united the people of the Cherokee Nation. There is not today and never has been a civilized Indian community on the continent which has not been largely made so by the immediate labors of Christian missionaries.1 -Nineteenth century Cherokee Citizen Mary Brown Advisor: Dr. Richard Boles May 7, 2015 “Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts of the City College of the City University of New York.” 1Timothy Hill, Cherokee Advocate, “Brief Sketch of the Mission History of the Cherokees,” (Tahlequah, OK) April 18, 1864. Table of Contents Thesis: The leaders of the Cherokee Nation during the nineteenth century were not only “Christian”, but they also used Christianity to heavily influence their nationalist movements during the 19th century. Ultimately, through laws and tenets a “Christian nation” was formed. Introduction: Nationalism and the roots Factionalism . Define Cherokee nationalism—citizenship/blood quantum/physical location. The historiography of factionalism and its primary roots. Body: “A Christian Nation”: How Christianity shaped a nation . Christianity and the two mission organizations. -

Origin and History of Seventh-Day Adventists, Vol. 1

Origin and History of Seventh-day Adventists FRONTISPIECE PAINTING BY HARRY ANDERSON © 1949, BY REVIEW AND HERALD As the disciples watched their Master slowly disappear into heaven, they were solemnly reminded of His promise to come again, and of His commission to herald this good news to all the world. Origin and History of Seventh-day Adventists VOLUME ONE by Arthur Whitefield Spalding REVIEW AND HERALD PUBLISHING ASSOCIATION WASHINGTON, D.C. COPYRIGHT © 1961 BY THE REVIEW AND HERALD PUBLISHING ASSOCIATION WASHINGTON, D.C. OFFSET IN THE U.S.A. AUTHOR'S FOREWORD TO FIRST EDITION THIS history, frankly, is written for "believers." The reader is assumed to have not only an interest but a communion. A writer on the history of any cause or group should have suffi- cient objectivity to relate his subject to its environment with- out distortion; but if he is to give life to it, he must be a con- frere. The general public, standing afar off, may desire more detachment in its author; but if it gets this, it gets it at the expense of vision, warmth, and life. There can be, indeed, no absolute objectivity in an expository historian. The painter and interpreter of any great movement must be in sympathy with the spirit and aim of that movement; it must be his cause. What he loses in equipoise he gains in momentum, and bal- ance is more a matter of drive than of teetering. This history of Seventh-day Adventists is written by one who is an Adventist, who believes in the message and mission of Adventists, and who would have everyone to be an Advent- ist. -

Legends, Traditions, and Laws of the Iroquois, Or Six Nations, and History of the Tuscarora Indians

Legends, Traditions, and Laws of the Iroquois, or Six Nations, and History of the Tuscarora Indians Elias Johnson The Project Gutenberg EBook of Legends, Traditions, and Laws of the Iroquois, or Six Nations, and History of the Tuscarora Indians by Elias Johnson Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this or any other Project Gutenberg eBook. This header should be the first thing seen when viewing this Project Gutenberg file. Please do not remove it. Do not change or edit the header without written permission. Please read the "legal small print," and other information about the eBook and Project Gutenberg at the bottom of this file. Included is important information about your specific rights and restrictions in how the file may be used. You can also find out about how to make a donation to Project Gutenberg, and how to get involved. **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **eBooks Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *****These eBooks Were Prepared By Thousands of Volunteers!***** Title: Legends, Traditions, and Laws of the Iroquois, or Six Nations, and History of the Tuscarora Indians Author: Elias Johnson Release Date: April, 2005 [EBook #7978] [This file was first posted on June 8, 2003] Edition: 10 Language: English Character set encoding: US-ASCII *** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK, LEGENDS, TRADITIONS, AND LAWS OF THE IROQUOIS, OR SIX NATIONS, AND HISTORY OF THE TUSCARORA INDIANS *** Editorial note: This E-text attempts to re-create the original text as closely as possible. -

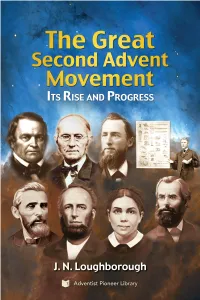

The Great Second Advent Movement.Pdf

© 2016 Adventist Pioneer Library 37457 Jasper Lowell Rd Jasper, OR, 97438, USA +1 (877) 585-1111 www.APLib.org Originally published by the Southern Publishing Association in 1905 Copyright transferred to Review and Herald Publishing Association Washington, D. C., Jan. 28, 1909 Copyright 1992, Adventist Pioneer Library Footnote references are assumed to be for those publications used in the 1905 edition of The Great Second Advent Movement. A few references have been updated to correspond with reprinted versions of certain books. They are as follows:— Early Writings, reprinted in 1945. Life Sketches, reprinted in 1943. Spiritual Gifts, reprinted in 1945. Testimonies for the Church, reprinted in 1948. The Desire of Ages, reprinted in 1940. The Great Controversy, reprinted in 1950. Supplement to Experience and Views, 1854. When this 1905 edition was republished in 1992 an additional Preface was added, as well as three appendices. It should be noted that Appendix A is a Loughborough document that was never published in his lifetime, but which defended the accuracy of the history contained herein. As noted below, the footnote references have been updated to more recent reprints of those referenced books. Otherwise, Loughborough’s original content is intact. Paging of the 1905 and 1992 editions are inserted in brackets. August, 2016 ISBN: 978-1-61455-032-7 4 | The Great Second Advent Movement J. N. LOUGHBOROUGH (1832-1924) Contents Preface 7 Preface to the 1992 Edition 9 Illustrations 17 Chapter 1 — Introductory 19 Chapter 2 — The Plan of Salvation -

Passion, Purpose & Power

JAMES R. NIX Recapturing the Spirit of the Adventist Pioneers Today Reminds us of the past and revives the same spirit of commitment and sacrifice evident in the Adventist pioneers in ministry leaders and disciples today! No matter what age we are, or what age we are in, the idea of sitting at the feet of someone who is telling a story brings back feelings of childhood awe, trust, and expectation. This book is an invitation to all ages, to sit and listen as these stories—told by the Adventist pioneers themselves—paint a picture of real people and their lives. These are stories of total commitment and incredible sacrifices that only a passion for Jesus, a dedication to His purposes, and the power of the Holy Spirit can generate! Draw close to the fireside of this second (updated and expanded) edition, and find yourself aglow with inspiration. Come, listen, and you might just hear the God of the pioneers call your name, sense a revival in your heart, and feel a renewed sense of mission in your life—one that draws from you a similar spirit of sacrifice and commitment! “We have nothing to fear for the future, except as we shall forget the way the Lord has led us, and His teaching in our past history.” —General Conference Bulletin, Jan. 29, 1893. COMPILED & EDITED BY JAMES R. NIX Recapturing the Spirit of the Adventist Pioneers Today Revised & Enlarged Formerly: The Spirit of Sacrifice & Commitment COMPILED & EDITED BY JAMES R. NIX PASSION, PURPOSE & POWER Copyright 2000, 2013 by Stewardship Ministries Department, General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists Design by Tami Pohle, Streamline Creative Most of the content of this book is taken from previously published works.