Marriott's Way Milemarkers and Sculpture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contents of Volume 14 Norwich Marriages 1813-37 (Are Distinguished by Letter Code, Given Below) Those from 1801-13 Have Also Been Transcribed and Have No Code

Norfolk Family History Society Norfolk Marriages 1801-1837 The contents of Volume 14 Norwich Marriages 1813-37 (are distinguished by letter code, given below) those from 1801-13 have also been transcribed and have no code. ASt All Saints Hel St. Helen’s MyM St. Mary in the S&J St. Simon & St. And St. Andrew’s Jam St. James’ Marsh Jude Aug St. Augustine’s Jma St. John McC St. Michael Coslany Ste St. Stephen’s Ben St. Benedict’s Maddermarket McP St. Michael at Plea Swi St. Swithen’s JSe St. John Sepulchre McT St. Michael at Thorn Cle St. Clement’s Erh Earlham St. Mary’s Edm St. Edmund’s JTi St. John Timberhill Pau St. Paul’s Etn Eaton St. Andrew’s Eth St. Etheldreda’s Jul St. Julian’s PHu St. Peter Hungate GCo St. George Colegate Law St. Lawrence’s PMa St. Peter Mancroft Hei Heigham St. GTo St. George Mgt St. Margaret’s PpM St. Peter per Bartholomew Tombland MtO St. Martin at Oak Mountergate Lak Lakenham St. John Gil St. Giles’ MtP St. Martin at Palace PSo St. Peter Southgate the Baptist and All Grg St. Gregory’s MyC St. Mary Coslany Sav St. Saviour’s Saints The 25 Suffolk parishes Ashby Burgh Castle (Nfk 1974) Gisleham Kessingland Mutford Barnby Carlton Colville Gorleston (Nfk 1889) Kirkley Oulton Belton (Nfk 1974) Corton Gunton Knettishall Pakefield Blundeston Cove, North Herringfleet Lound Rushmere Bradwell (Nfk 1974) Fritton (Nfk 1974) Hopton (Nfk 1974) Lowestoft Somerleyton The Norfolk parishes 1 Acle 36 Barton Bendish St Andrew 71 Bodham 106 Burlingham St Edmond 141 Colney 2 Alburgh 37 Barton Bendish St Mary 72 Bodney 107 Burlingham -

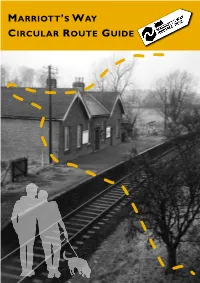

Marriott's Way Circular Route Guide

MARRIOTT’S WAY CIRCULAR ROUTE GUIDE WELCOME TO MARRIOTT’S WAY MARRIOTT’S WAY is a 26-mile linear trail for riders, walkers and cyclists. Opened in 1991, it follows part of the route of two former Victorian railway lines, The Midland and Great Northern (M&GN) and Great Eastern Railway (GER). It is named in honour of William Marriott, who was chief engineer and manager of the M&GN for 41 years between 1883 and 1924. Both lines were established in the 1880s to transport passengers, livestock and industrial freight. The two routes were joined by the ‘Themelthorpe Curve’ in 1960, which became the sharpest bend on the entire British railway network. Use of the lines reduced after the Second World War. Passenger traffic ceased in 1959, but the transport of concrete ensured that freight trains still used the lines until 1985. The seven circular walks and two cycle loops in this guide encourage you to head off the main Marriott’s Way route and explore the surrounding areas that the railway served. Whilst much has changed, there’s an abundance of hidden history to be found. Many of the churches, pubs, farms and station buildings along these circular routes would still be familiar to the railway passengers of 100 years ago. 2 Marriott’s Way is a County Wildlife Site and passes through many interesting landscapes rich in wonderful countryside, wildlife, sculpture and a wealth of local history. The walks and cycle loops described in these pages are well signposted by fingerposts and Norfolk Trails’ discs. You can find all the circular trails in this guide covered by OS Explorer Map 238. -

Breckland Local Plan Consultation Statement 1

Region 1. Introduction 2 2. Issues and Options 3 3. Preferred Directions 5 4. Proposed Sites and Settlement 7 Boundaries 5. General and Specific Consultees 9 6. Conformity with the Statement of 16 Community Involvement Breckland Local Plan Consultation Statement 1 1 Introduction 1.1 This statement of consultation will be submitted to the Secretary of State as part of the examination of the Breckland Local Plan. The statement sets out the information required under Regulation 22 (c) of the Town and Country Planning (Local Planning) (England) Regulations 2012. This statement shows: Who was consulted; How they have been consulted; A summary of the issues raised How issues have been addressed within the Local Plan. 1.2 The 2012 Local Planning Regulations sets out the stages of consultation that a Local Plan is required to go through prior to its submission to the Secretary of State. These are: Regulation 18: a consultation whereby the local authority notifies of their intention to prepare a Local Plan and representations are invited about what the Local Plan should contain Regulation 19: prior to submitting the Local Plan to the Secretary of State, the proposed submission document is made available to the general consultation bodies and the specific consultation bodies. 1.3 In accordance with the regulations and Breckland's Statement of Community Involvement, the Local Plan has been subjected to a number of consultation periods. These are summarised below: Regulation 18: Issues and Options consultation Regulation 18: Preferred Directions consultation Regulation 18: Preferred Sites and Settlement Boundaries consultation 1.4 Full details of each of these consultations is included within this statement. -

Norfolk Map Books

Scoulton Wicklewood Hingham Wymondham Division Arrangements for Deopham Little Ellingham Attleborough Morley Hingham County District Final Recommendations Spooners Row Yare & Necton Parish Great Ellingham Besthorpe Rocklands Attleborough Attleborough Bunwell Shropham The Brecks West Depwade Carleton Rode Old Buckenham Snetterton Guiltcross Quidenham 00.375 0.75 1.5 Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016 © Crown copyright and database rights 2016 OSGD New Buckenham 100049926 2016 Tibenham Bylaugh Beetley Mileham Division Arrangements for Dereham North & Scarning Swanton Morley Hoe Elsing County District Longham Beeston with Bittering Launditch Final Recommendations Parish Gressenhall North Tuddenham Wendling Dereham Fransham Dereham North & Scarning Dereham South Scarning Mattishall Elmham & Mattishall Necton Yaxham Whinburgh & Westfield Bradenham Yare & Necton Shipdham Garvestone 00.425 0.85 1.7 Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016 © Crown copyright and database rights 2016 OSGD Holme Hale 100049926 2016 Cranworth Gressenhall Dereham North & Scarning Launditch Division Arrangements for Dereham South County District Final Recommendations Parish Dereham Scarning Dereham South Yaxham Elmham & Mattishall Shipdham Whinburgh & Westfield 00.125 0.25 0.5 Yare & Necton Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016 © Crown copyright and database rights 2016 OSGD 100049926 2016 Sculthorpe Fakenham Erpingham Kettlestone Fulmodeston Hindolveston Thurning Erpingham -

Arable Land for Sale by Private Treaty Kerdiston Road | Themelthorpe

Irelands Agricultural TG0624 3005 Arable Land For Sale by Private Treaty A single parcel of Grade III arable land extending to approximately0 50 100 150m 12.66 Ha (31.28 Ac) Kerdiston Road | Themelthorpe | Dereham | Norfolk | NR20 5PT DESCRIPTION BASIC PAYMENT SCHEME The property is registered with the Rural Payments Agency and is A single parcel of productive arable land extending to approximately eligible for claiming the Basic Payment Scheme. 12.66Ha of Basic 12.66 Ha (31.28 Acres) with frontage onto Kerdiston Road. The land is Payment Scheme entitlements are included as part of the sale. There gently undulating with the boundaries comprising a combination of will be no apportionment of the 2020 Basic Payment and the purchaser trees, hedges and ditches. The land is accessed directly off Kerdiston will be required to indemnify the vendor against any breaches in Cross Road and benefits from three separate access points. Compliance from completion through to 31st December. The land is classified as being Grade III with soils of the Beccles and EARLY ENTRY Aldeby soil series known to be loamy and clayey; drift over chalky till. Early entry may be available subject to payment of an additional 10% The land has been in arable production for many years and has formed deposit. part of a combinable and root crop rotation. PLANNING LOCATION The property is within the jurisdiction of Broadland District Council, The property is located to the east of the village of Themelthorpe, to whom interested parties are advised to make their own enquiries in approximately 3.0 miles north west of Reepham and approximately 11.0 respect of any planning issues and development opportunities for the miles west of Aylsham. -

Newsletter Date: January, 2017

Date: Nov 2018 Newsletter Date: January, 2017 Message from Inspector Brian Sweeney Welcome to the newsletter for Reepham, Cawston, Foulsham, Guestwick, Heydon, Salle, Themelthorpe, Wood Dalling, Alderford, Attlebridge, Booton, Brandiston, Great Witchingham, Haveringland, Honingham, Little Witchingham, Morton on the Hill, Ringland, Swannington and Weston Longville. Our aim is to ensure you receive regular updates on crime levels along with relevant news and crime prevention advice. We will inform you of any opportunities to meet the local policing team and encourage you to advertise these within your parish newsletters and magazines. Working together helps the police understand the issues and concerns that matter to the public helping us to maintain a place to live that we can all be proud of. Crime Updates 1st - 31st Oct 2018 Offence Numbers What could this entail Arson 0 Damage caused as a result of fire. Anti-Social Behaviour (ASB) 1 Harassment, alarm or distress is caused in a non-crime incident. Burglary Business and Community 3 Business and community Burglaries will include shops, businesses and other property. In general, the purpose for which a building is designed will determine whether it should be classified as ‘Residential’ or ‘Business and Community’. Burglary Residential 0 Residential Burglary will encompass entry to any building within the curtilage/boundary of a residence, e.g. garden sheds and garages. Criminal Damage 2 A person destroys or damages property belonging to someone else. Domestic 7 Domestic incidents where a crime has not occurred. Parties are aged 16 or over and have been intimate partners or family members regardless of sexu- ality. -

Norfolk Research Specialist FAMILY HISTORY (Since 1982) RESEARCH

The Norfolk Ancestor Volume Six Part Two Also a Digby? On the back of this photo it says "Treble, Artist and Photographer, Victoria Hall, Norwich Victoria Artist and Photographer, "Treble, JUNE 2009 William Digby William The Journal of the Norfolk Family History Society formerly Norfolk & Norwich Genealogical Society The man's photo is unnamed. On the back of the woman's photo is the name Mary Clack July 1899. Could they be members of your family? See the paragraph on the Editor's letter page. Mary Ann Digby Judith Digby NORFOLK FAMILY HISTORY SOCIETY A private company limited by guarantee Registered in England, Company No. 3194731 Registered as a Charity - Registration No. 1055410 Registered Office address: Kirby Hall, 70 St. Giles Street, ______________________________________________________________________________ HEADQUARTERS and LIBRARY Kirby Hall, 70 St Giles Street, Norwich NR2 1LS Tel: (01603) 763718 Email address: [email protected] NFHS Web pages:<http://www.norfolkfhs.org.uk BOARD OF TRUSTEES Malcolm Cole-Wilkin (P.R. Transcripts) Denagh Hacon (Editor, Ancestor) Brenda Leedell (West Norfolk Branch) Pat Mason (Company Secretary) Mary Mitchell (Monumental Inscriptions) Edmund Perry (Projects Coordinator) Colin Skipper (Chairman) Jean Stangroom (Membership Secretary) Carole Taylor (Treasurer) Patricia Wills-Jones (East Norfolk Branch, Strays) EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Denagh Hacon (Editor) Edmund Perry (Assistant Editor) Julie Hansell (Copy Typist) Current Rates for Membership: UK Membership: £10.00 per year. Overseas Airmail £12.00 -

Old Cemetery Reepham with Kerdiston

GUIDE TO THE OLD CEMETERY REEPHAM WITH KERDISTON In 1856 the churchyard at the centre of the town of Reepham, in which the dead of the three parishes of Reepham-with-Kerdiston, Whitwell and Hackford had been buried for a thousand years or so, was closed. (Kerdiston church, out towards Themelthorpe, had been downgraded to a chapel as early as the 14th century and its burials took place within the Reepham area of the triple churchyard). Two new cemeteries were now laid out; that for Reepham-with-Kerdiston was in Norwich Road, that serving both Whitwell and Hackford was in Whitwell Road. In 1935 the Reepham cemetery was closed; burials of Reepham folk had already begun to take place in the Whitwell Road cemetery as early as 1922, but now the dead of all three parishes were laid to rest there. It is still in use and sometimes inaccurately called the New Cemetery. At the 1856 Reepham cemetery, an area of unconsecrated land was provided for non-Anglican burials. The vicar of the day refused to enter these in the church register, stating they were “non- Christian” interments, so a separate cemetery register was kept. However there are some burials that are recorded in neither of these. Those buried here in the Old Cemetery, in addition to residents of Reepham, include a number from Aylsham Union Workhouse (to which they would have been taken in indigence) and several from Thorpe Lunatic Asylum and the Norfolk and Norwich Hospital. There are quite a number from Hackford and Whitwell despite the fact that those parishes had their own cemetery. -

UNREASONABLE SITES - RESIDENTIAL VILLAGE CLUSTERS – Broadland

UNREASONABLE SITES - RESIDENTIAL VILLAGE CLUSTERS – Broadland Address Site Reference Area Promoted for Reason considered to be (ha) unreasonable Blofield Heath Blofield Nurseries, Hall GNLP0099 2.85 Up to 25 This site is considered to Road dwellings be unreasonable for allocation as it is located some way beyond the built edge of the village with no safe pedestrian route to Hemblington Primary School. Development of this site would not be well related to the form and character of the settlement. Land to the west of GNLP0288 1.43 24 dwellings This site is considered to Woodbastwick Road be unreasonable for allocation as the planning history suggests there are access constraints which means that the site would only be suitable for small scale development off a private drive. It therefore would not be able to accommodate the minimum allocation size of 12-15 dwellings. Land east of Park GNLP0300 0.78 Residential Although this site is Lane (unspecified adjacent to the existing number) settlement limit it is considered to be unreasonable for allocation as there is no continuous footway to Hemblington Primary School. There is a better located site to meet the capacity of the cluster. Dawson’s Lane GNLP2080 2.65 42 dwellings Although this site is adjacent to the existing settlement limit it is considered to be unreasonable for allocation as there is no continuous footway to Hemblington Primary School. There is a better located site to meet the capacity of the cluster. In addition, the proposed access to the site is Address Site Reference Area Promoted for Reason considered to be (ha) unreasonable currently a narrow track with an unmade surface which would need upgrading to be acceptable. -

Copeman – the Evolution of a Norfolk Surname by William Vaughan-Lewis ………………………………………………………256

AYLSHAM LOCAL HISTORY SOCIETY Volume 8 No 9 August 2010 The JOURNAL & NEWSLETTER is the publication of the Aylsham Local History Society. It is published three times a year, in April, August and December, and is issued free to members. Contributions are welcomed from members and others. Please contact the editor: Dr Roger Polhill, Parmeters, 12 Cromer Road, Aylsham NR11 6HE [email protected] 01263 733424 Chairman: Dr Roger Polhill Secretary: Mr Jim Pannell 01263 731087 [email protected] Aylsham Town Archivist: Mr Lloyd Mills [email protected] CONTENTS Editorial …………………………………………………………….. 255 Copeman – the Evolution of a Norfolk Surname by William Vaughan-Lewis ………………………………………………………256 Robert Copeman of Itteringham and his connections to Aylsham by William Vaughan-Lewis …………………………………………265 Frederick Copeman and the Aylsham Steam Mill by Phil Bailey ….. 272 Society News ……………………………………………………….. 278 Visit to Marshland Churches by Tony Shaw ……………………….. 278 Norwich Silver – a talk by Francesca Vanke – Gillian Fletcher …… 282 Notices ……………………………………………………………… 284 Correction. Volume 8, No. 8, p. 248, end of para. 3: for Shipdham read Shipden. Cover illustration: White House farm, once Itteringham Hall, home of Robert and Lee Blanche Copeman and their family. 254 AYLSHAM LOCAL HISTORY SOCIETY JOURNAL & NEWSLETTER Volume 8 No. 9 Many thanks to Phil Bailey (an Australian descendant of Robert Copeman of Itteringham) and William Vaughan-Lewis for rounding off the series on the Copeman family, who had such a significant influence on Aylsham during the nineteenth century. Our imagination was directed to much earlier achievements by the most memorable excursion to the glorious Marshland churches in early July. Now we look forward to our Open Day on the 12th of September, advertised on the back cover, and the beginning of a new season. -

The Memories Ofseven Norfolk People

Hikey Sprites will be after you, if you are naughty’. I E didn't know what they were, I think a sort of fairy - thing, but I knew they would come after me. It can be Weknew the Hey prites Re The memories of seven Norfolk people Hikey or Hiker”. LE PE A A Val a Bob (89) = in Fakenham 12-5-2008 \ Met Met in the Forum Norwich 17-4-2009 P y — da “There were some council houses in Kirby Bedon, 1 had Ms “Mum talked about Hikey Sprites, they came out in on the way home from school. to pass them every day the dark, of course there was no electricity then.I spent one, she always used to | An old lady lived in the last my childhood in Griston. Older children used to dare say as we passed, “Hurry you home girl, before them me to walk past a gap in a hedge, where a hose from a know what they were, Highty Sprites get you’. didn’t traction engine passed through, they said the Hikey get home”. but I was glad to Sprites were there”. Bob,reliving his fear, demonstrated in the Forum how he gingerly crept Nigel (65) past that gap. 1-7-2009 Metat the Royal Norfolk Show | Nigel gave me information butalso said he would make enquiries of his ninety-two year old mother when he visited her. He later rang me with his Met in Southrepps 21-10-2008 findings. “We spent our childhood in Themelthorpe. When we “It was a night-time thing, everyone in Kerdistone were kids mum would say, if we were naughty, ‘The used to talk about them. -

Accommodation

West Norfolk HOLIDAY Guide 2019 DISCOVER KING’S LYNN a town brim full of history and heritage Enjoy the classic seaside resort of HUNSTANTON Explore west Historic Where Norfolk towns to stay Wonderful walking, Visit castles, Find your perfect super cycling, brilliant houses, priories and place to stay, bird watching, exhilarating market squares whatever your From page 14From water sports page 8 From page 27 From requirements WELCOME to west Norfolk, a truly special place of unspoilt charm and natural beauty. Renowned for its superb coastline, much of it an ‘Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty’, this wonderful part of Norfolk is the ideal place to relax, unwind & soak up the sheer sense of space & tranquillity. The Castle Acre castle ruins 3 CONTENTS 4 – 5 Rural escape 6 – 7 Time to relax 8 – 9 Fabulous Heritage 10 – 11 Discover King's Lynn 12 – 13 Fun on the beach 14 – 15 Rural and coastal pursuits 16 – 17 West Norfolk After Hours 18-19 Finding your accommodation 20 Guide to gradings 21 Guide to adverts and symbols used 22 – 23 Map of West Norfolk (map 1) 24 In and around King's Lynn (map 2) 25 In and around Downham Market (map 3) 26 In and around Hunstanton (map 4) 27 – 29 Hotels and Guest accommodation 30 – 32 Self catering accommodation 33 Holiday, Touring and Camping parks 34 – 37 Attractions, Places to visit and Entertainment venues 38 – 41 Events and festivals 42 Travel information 43 Tourist information Bienvenue dans le West Norfolk, un lieu unique en Angleterre, riche en histoire, aux nombreux villages pittoresques et avec une cam- pagne splendide.