Fenton 1 Toward the Epicene: Mechanisms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Masses Index 1911-1917

The Masses Index 1911-1917 1 Radical Magazines ofthe Twentieth Century Series THE MASSES INDEX 1911-1917 1911-1917 By Theodore F. Watts \ Forthcoming volumes in the "Radical Magazines ofthe Twentieth Century Series:" The Liberator (1918-1924) The New Masses (Monthly, 1926-1933) The New Masses (Weekly, 1934-1948) Foreword The handful ofyears leading up to America's entry into World War I was Socialism's glorious moment in America, its high-water mark ofenergy and promise. This pregnant moment in time was the result ofdecades of ferment, indeed more than 100 years of growing agitation to curb the excesses of American capitalism, beginning with Jefferson's warnings about the deleterious effects ofurbanized culture, and proceeding through the painful dislocation ofthe emerging industrial economy, the ex- cesses ofspeculation during the Civil War, the rise ofthe robber barons, the suppression oflabor unions, the exploitation of immigrant labor, through to the exposes ofthe muckrakers. By the decade ofthe ' teens, the evils ofcapitalism were widely acknowledged, even by champions ofthe system. Socialism became capitalism's logical alternative and the rallying point for the disenchanted. It was, of course, merely a vision, largely untested. But that is exactly why the socialist movement was so formidable. The artists and writers of the Masses didn't need to defend socialism when Rockefeller's henchmen were gunning down mine workers and their families in Ludlow, Colorado. Eventually, the American socialist movement would shatter on the rocks ofthe Russian revolution, when it was finally confronted with the reality ofa socialist state, but that story comes later, after the Masses was run from the stage. -

A HISTORY of the GREAT WAR APRIL, 1915 Ten Cents

A HISTORY OF THE GREAT WAR APRIL, 1915 Ten Cents Do you want a history of the Great War in its larger social and revolutionary aspects? Interpreted by the foremost Socialist thinkers? The following FIVE issues of the NEW REVIEW consti- tute the most brilliant history extant: evew FEBRUARY, 1915, ISSUE "A _New International," by Anton Pannekoek; "Light and Shade of the Great War," by H. M. Hyndman; "Against the 'Armed Nation' or 'Citizen Army,' " by F. A CRITICAL SURVEY OF INTERNATIONAL SOCIALISM M. Wibaut, of Holland; "The Remedy for War: Anti-Nationalism," by William Eng- lish Walling; "A Defense of the German Socialists," by Thomas C. Hall, D.D.; the SOCIALIST DIGEST contains: Kautsky's "Defense of the International;" "A Criti- cism of Kautsky:" A. M. Simons' attack on the proposed Socialist party peace pro- gram; "Bourgeois Pacifism;" "A Split Coming in Switzerland?" "Proposed Peace Program of the American Socialist Party;" "Messages from Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemberg," etc. THE BERNHARDI SCHOOL JANUARY, 1915, ISSUE "A Call for a New International;" "Capitalism, Foreign Markets and War," by Isaac A. Hourwich; "The Future of Socialism," by Louis^ C. Fraina; "As to Making OF SOCIALISM Peace," by Charles Edward Russell; "The Inner Situation in Russia," 677 Paul Axelrod; "Theory, Reality and the War," by Wm. C. Owen; the SOCIALIST DIGEST contains: "Kautsky's New Doctrine," "Marx and Engels Not Pacifists," by Eduard Bernstein; "An American Socialist Party Resolution Against Militarism;" "The International By Isaac A. Hourwick Socialist Peace Congress;" "A Disciplining of Liebknecht?" "German Socialists and the War Loans;" "Militarism and State Socialism," etc. -

By Floyd Dell

), AUGUST I9I8 15 CENTS J Ss You Ever A Child? By Floyd Dell John Brown: A Biography DRESS THE END OF THE WAR Fifty Years after by Walter Weyl is an emphasis upon all that has By been written on_ the problem of Oswald Garrison Villard world reconstruction. Dr. Weyl is ‘one of those who believes that de- { Book Every Radical and mocraey must triumph, not by foree of arms alone, but by’ the foree of principles and ideals, Price: $2. IN THE FOURTH YEAR by H. G. Wells tion "after four years of bloodshed probleme fa Lad’s Love tne of the f A Little Book of Rebel Verse by Jamés Waldo Fawcett WHAT IS NATIONAL HONOR? Pally itustrat by Leo Perla (troduction by Norman Angell) it thrills! complete analysis of the HOUGHTON Address, ‘eal, ethical and political nd of “national hi COMPANY ‘The Dawn Associates, \ worthy contribution to the Publi ature of internationalism, 181 Clare $1.50. New York City Price, $1.00 RECORD. OF NEW QUAKER CONS! PHILIP Cyrus Pri Bote troduction GOODMAN tells of the mental and ph BOOKS The Cu-nperatine League trials suffered by a young Quaker of America drafted in 1863, Price: 6 cont 2 West New Thirteenth York City Strert HISTORY of LABOR in AMN! A BOOK the UNITED S' OF CALUM by John R. Commons and By H, L. ME Forty summary (in two vol: Essays of fulmination ory of labor in the States. Is based on original A BOOK WITHOUT Price: $6.50. TLE DRGE JEAN NATHAN The Co-operative Consumer” Prose-pocms ip 90c THEORIES OF SOCIAL PROGRESS | HOW'S YOUR MSS. -

November, 1915 10 Cents Adventures in Anti—Land

NOVEMBER, 1915 10 CENTS stoant pavig ADVENTURES IN ANTI—LAND—Floyd Dell LABOR AND THE FUTURE—Amos Pinchot CONFESSION OF A SUFFRAGE ORATOR—Max Eastman THE SANGER VERDICT The Sexual Question MasSsSEsS OCTOBER 20TH By Avouy P is the date on which Max Eastman‘s Winter Lecture Tour from the (Z THIS Magazine is Oun— Atlntieto the Paciie Const will be fally arranged.. Mr. Eastman has ed and Published Co— been in Europe this summer and will tel what he thinks about Reproduction and. Evolution operatively by its Ed: of ‘Living Beings—Love~— . itore, It has no Dividends WAR AND THE SOCIALIST FAITH Secut Pathology—Religion to Pay, and nobody is try— Hi other ecturesare and Sexual Life—Medic ing to make Money out of and Sexual Life—Sexal Mo— it. A Revolutionary: and REVOLUTIONARY PROGRESS raliy—The Sexual Question not a Reform Magazin Is there any, and what is it? in Politcs, in Pedagogy, in Magazine with a Sense of Ant. Cotraceptives dis— Humor and no Respect for FEMINISM AND HAPPINESS cussed th, S550.. Rec— the Respectable; Frank; An address delivered before the Chicago Woman‘s Club ommended by Max Eastman Arrogant; Impertinent; foseat e Tok infi mete n hewame BP7 in ie Searching for the True Calage Te Sime book, cheaper ‘binting, Causes; a Magazine Di— WHAT IS HUMOR AND WHY? naw $1.do rected againet Rigidity Eirst delivered as "A Humorous Talk" at the anval banquet of the and Dogma wherever it is Chaiber of Commerce, at Syracuse, N, ¥. President Wilion said on Psychopathia Sexualis found; Printing what is that ccasion that it was "the most delightfil combination of thought too Naked or Trus for a and humor he had ever listened to By Dx. -

Literary Miscellany

Literary Miscellany Including Fine Printing, Artist’s Books, And Books & Manuscripts In Related Fields. Catalogue 329 WILLIAM REESE COMPANY 409 TEMPLE STREET NEW HAVEN, CT. 06511 USA 203.789.8081 FAX: 203.865.7653 [email protected] www.williamreesecompany.com TERMS Material herein is offered subject to prior sale. All items are as described, but are consid- ered to be sent subject to approval unless otherwise noted. Notice of return must be given within ten days unless specific arrangements are made prior to shipment. All returns must be made conscientiously and expediently. Connecticut residents must be billed state sales tax. Postage and insurance are billed to all non-prepaid domestic orders. Orders shipped outside of the United States are sent by air or courier, unless otherwise requested, with full charges billed at our discretion. The usual courtesy discount is extended only to recognized booksellers who offer reciprocal opportunities from their catalogues or stock. We have 24 hour telephone answering and a Fax machine for receipt of orders or messages. Catalogue orders should be e-mailed to: [email protected] We do not maintain an open bookshop, and a considerable portion of our literature inven- tory is situated in our adjunct office and warehouse in Hamden, CT. Hence, a minimum of 24 hours notice is necessary prior to some items in this catalogue being made available for shipping or inspection (by appointment) in our main offices on Temple Street. We accept payment via Mastercard or Visa, and require the account number, expiration date, CVC code, full billing name, address and telephone number in order to process payment. -

Early Years and Avant Garde Ideas the Little Review in Chicago

LECTURE “Early Years and Avant Garde Ideas The Little Review in Chicago” ©Susan Platt first presented in conjunction with a conference on the Avant Garde in Chicago, sponsored by the Smithsonian Institution, 1988, published in The Old Guard and the Avant-Garde, Modernism in Chicago, 1910 – 1940, University of Chicago Press, 1990 While severe floods created widespread disaster in Illinois in the Spring of 1913 established cultural circles in Chicago battled a flood of another type, coming not from natural forces, but from the artistic world of New York: the International Exhibition of Modern Painting, known in Chicago as the Post Impressionist Exhibition, invaded the staid bourgeois cultural circles of the city. A self respecting matron and mother, reported to the director of the Chicago Art Institute, Mr. WIlliam French, who had left town for the duration of the fracas, that a distinguished "alienist,." (expert in insanity) had visited the exhibition declared the art to be the work of a. distortionists b. psychopathologists and c. geometric puzzle artists. Of the three threats to society the least frightening appeared to be the last. The matron was concerned, she confided in Mr. French, for the moral and mental well being of her daughter. Yet even as the bourgeois sector of Chicago feared for their lives and those of their offspring, another dimension of Chicago's cultural scene was enlivened and invigorated by this same exhibition. I refer not to the students at the Art Institute (many of whom violently opposed the exhibition as suggested by their burning of Henri Matisse in effigy) but to the literary and political avant-garde of Chicago in 1913. -

THE SOCIALISM of the SWORD 25 the NOVELS of DOSTOEVSKY 38 Louis C

May Ten 15th Review Cents A CRITICAL SURVEY OF INTERNATIONAL SOCIALISM VOL. III. 10c a Copy. Putlisned on tke first and fifteentk of tke montn. * 6<> a Year- No. 6 CONTENTS PAGE PAGE THE SOCIALISM OF THE SWORD 25 THE NOVELS OF DOSTOEVSKY 38 Louis C. Fraina. Floyd Dell. CURRENT AFFAIRS 27 BOOK REVIEWS 39 L. B. Boudin. TREITSCHKE;; GERMAN SOCIALIST WAR LITERATURE; REVOLUTIONARY THE WAR IN THE FAR EAST 29 FUTURE OF RUSSIA. Nicholas Russel. A SOCIALIST DIGEST 41 "THE CONSCIENCE OF THE NORTH" 32 THE TREND TOWARD STATE SOCIALISM IN THE BELLIGERENT NATIONS; Covington Hall. THE GERMAN SOCIALISTS' PEACE TERMS; THE BRITISH SOCIALISTS SOLIDARITY AND SCABBING 34 AND PEACE; INTERPRETING JAPAN'S DEMANDS UPON CHINA; BERN- Austin Lewis. STEIN AND THE FRENCH SOCIALSTS. BILLY SUNDAY AS A SOCIAL SYMPTOM 36 CORRESPONDENCE 45 Phillips Russell. From Felix Grendon; Floyd Dell. Copyright, 1915, by the New Review Publishing Ass'n. Reprint permitted if credit is given. The Socialism of the Sword By Louis C. Fraina HE military State Socialism imposed upon the war. Now, however, these constructive changes oc- belligerent nations by implacable necessity cur in the midst of war itself. While the armies of T is not a new phenomenon in the scope of its the nations slaughter each other, the state organizes purpose; it is a new phenomenon in its application and transforms the internal social system. The Na- and social consequences. poleonic wars destroyed the old order of things in The theory of the older Socialism of the Sword Europe, but except in France the new order was was lucidly stated by Benjamin Franklin. -

![Ex Libris. Paris : American Library in Paris, 1923-[1925]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5295/ex-libris-paris-american-library-in-paris-1923-1925-2865295.webp)

Ex Libris. Paris : American Library in Paris, 1923-[1925]

Ex libris. Paris : American Library in Paris, 1923-[1925] https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.$b199672 Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives http://www.hathitrust.org/access_use#cc-by-nc-nd-4.0 This work is protected by copyright law (which includes certain exceptions to the rights of the copyright holder that users may make, such as fair use where applicable under U.S. law), but made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives license. You must attribute this work in the manner specified by the author or licensor (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Only verbatim copies of this work may be made, distributed, displayed, and performed, not derivative works based upon it. Copies that are made may only be used for non-commercial purposes. Please check the terms of the specific Creative Commons license as indicated at the item level. For details, see the full license deed at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0. - - - .-- | JUNE 1925 9 - Number - - : ooooo - -o - - The of Two of the Cities" Paris -“Tale - - - - - . Certain Books on the Negro MARY warre ovingtoN- - - - The fruisingian Entente: Abbé - Félix Klein Selected French Book * Book Reviews - Me (* Magazines' leas, - Current -S- \ PAR's - | BREAKFAST HOT BREADS LUNCHEON GRIDDLE CAKES AFTERNOON TEA AND MANY OTHER LIGHT SUPPER AMERICAN DELICACIES RIVOLI TEA ROOMS 2. Rue de l'Echelle. 2 (NEAR LOUVRE AND PALAIS ROYAL) R. C. Seine 240.431 "A COSY CORNER IN A CROWDED CITY1' ENGLISH AND AMERICAN HOME COOKING 9 A. M. to 8.30 P. -

Floyd Dell and Edna St. Vincent Millay at the Newberry Library

QUICK GUIDE Floyd Dell and Edna St. Vincent Millay at the Newberry Library How to Use Our Collection The Newberry is an independent research library; readers do not check books out to take home, but consult materials here. We welcome into our reading rooms researchers who are at least 14 years old or in the ninth grade. Creating a free reader account and requesting collection items takes just a few minutes. Please visit https://requests.newberry.org to begin the registration process and to start exploring our collection; when you arrive at the Newberry for research, a free reader card will be issued to you in our third-floor reference center. For further information about our collection and public programs, please visit www.newberry.org. Selection of Notable Works by Floyd Dell The Briary-Bush. New York: A.A. Knopf, 1921. Dell’s Homecoming; An Autobiography. Port Washington, NY: sequel to his first novel, Moon-Calf. Call #: Y 255 Kennikat Press, c. 1933; reprint 1969. Call #: 4A 9660 .D373 Moon-Calf. New York: A.A. Knopf, 1920. Dell’s coming- Diana Stair. New York: Farrar & Rinehart, c. 1932. A of-age story and his most popular novel. Call #: Y 255 novel about a “modern” woman who is by turns a .D377 schoolteacher, factory worker, strike leader, poet, participant in the “free love” movement, and member of The Provincetown Plays. First Series, Containing Bound East for a Socialist commune. Call #: Y 255 .D3733 Cardiff, by Eugene O’Neill; The Game, by Louise Stevens Bryant; and King Arthur’s Socks, by Floyd Dell. -

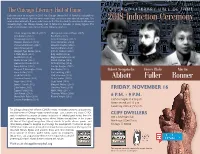

2018 Induction Ceremony Program

The Chicago Literary Hall of Fame CHICAGO LITERARY HALL OF FAME Each year since its inception in 2010, the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame has inducted our best historical writers. Until the most recent class, six writers were selected each year. The number was reduced to three in order to ensure that the standards for selection would remain 2018 Induction Ceremony incredibly high. Our Chicago Literary Hall of Fame now includes 45 literary figures. The induction ceremonies take place in the year following selection. Robert Sengstacke Abbott (2017) Alice Judson Ryerson Hayes (2015) Jane Addams (2012) Ben Hecht (2013) Nelson Algren (2010) Ernest Hemingway (2012) Margaret Anderson (2014) David Hernandez (2014) Sherwood Anderson (2012) Langston Hughes (2012) Rane Arroyo (2015) Fenton Johnson (2016) Margaret Ayer Barnes (2016) John H. Johnson (2013) L. Frank Baum (2013) Ring Lardner (2016) Saul Bellow (2010) Edgar Lee Masters (2014) Marita Bonner (2017) Harriet Monroe (2011) Gwendolyn Brooks (2010) Willard Motley (2014) Fanny Butcher (2016) Carolyn Rodgers (2012) Margaret T. Burroughs (2015) Mike Royko (2011) Cyrus Colter (2011) Carl Sandburg (2011) Robert Sengstacke Henry Blake Marita Floyd Dell (2015) Shel Silverstein (2014) Theodore Dreiser (2011) Upton Sinclair (2015) Abbott Fuller Bonner Roger Ebert (2016) Studs Terkel (2010) James T. Farrell (2012) Margaret Walker (2014) Edna Ferber (2013) Theodore Ward (2015) FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 16 Eugene Field (2016) Ida B. Wells (2011) Leon Forrest (2013) Thornton Wilder (2013) Henry Blake Fuller (2017) Richard Wright (2010) 6 P.M. - 9 P.M. Lorraine Hansberry (2010) Cash bar begins at 4:30 p.m. Dinner served at 6:15 p.m. -

1 the Founding: Myth and History

Cambridge University Press 0521838525 - The Provincetown Players and the Culture of Modernity Brenda Murphy Excerpt More information 1 The founding: myth and history HE FOUNDING OF THE PROVINCETOWN PLAYERS IS AN EVENT T that has grown beyond legend to assume the status of myth in the annals of the American theatre. Its significance is paramount because, as theatre historians have recognized, the Provincetown, with its nurturance of self-consciously literary American playwrights like Susan Glaspell, Edna St. Vincent Millay, and Eugene O’Neill, has come to represent a new conception of the theatre in the United States. The Provincetown is now seen as the major progenitor of experimental non-commercial theatre in America, the pioneering group that taught theatre practitioners how to develop, nurture, and practice theatre as an art in a country where theatre had always been almost exclusively a business. The growth of the Provincetown myth has been helped by the fact that, as Robert Sarlo´s has noted, ‘‘the group’s first stirrings remain a mystery, about which many myths but few facts survive. Accounts, even by participants, are contra- 1 dictory.’’ As early as 1931, the first published full-length history of the Provincetown, by Helen Deutsch and Stella Hanau, noted that the story of the founding in the summer of 1915 had been told so often that it was already assuming the form of legend: Magazines, newspapers, personal biographies, and histories of the thea- ter have carried accounts of the picturesque beginnings until even the phraseology -

Theodore Dreiser Bibliography

Theodore Dreiser Bibliography Donald Pizer: THEODORE DREISER, a primary bibliography and reference guide for more info please contact [email protected] Theodore Dreiser Bibliography Title: THEODORE DREISER, a primary bibliography and reference guide Author: Donald Pizer Author: Richard W. Dowell Author: Frederic E. Rusch Print Source: THEODORE DREISER, a primary bibliography and reference guide Donald Pizer Richard W. Dowell Frederic E. Rusch Second Edition Boston: G.K. Hall & Co., 1991 ISBN: 0-8161-8976-5 View entire text or view in sections below (all as PDF files). Donald Pizer: THEODORE DREISER, a primary bibliography and reference guide The following sections are individual pdf files. Section One Titlepage Contents Preface to the Second Edition Writings by Theodore Dreiser A. Books, Pamphlets, Leaflets, and Broadsides AA. Collected Editions B. Contributions to Books and Pamphlets C. Contributions to Periodicals (Newspapers and Journals) D. Miscellaneous Separate Publications E. Published Letters F. Interviews and Speeches G. Productions and Adaptations H. Library Holdings Index to Primary Bibliography Writings about Theodore Dreiser, 1900–1989 Introduction Criticism Biographical Studies Editorial Policies Reference Guide Index of Authors, Editors, and Translators Subject Index for more info please contact [email protected] Theodore Dreiser Bibliography Donald Pizer: THEODORE DREISER, a primary bibliography and reference guide Theodore Dreiser: A Primary and Secondary Bibliography, by Donald Pizer, Richard W. Dowell, and Frederic E. Rusch, was published by G.K. Hall & Company in 1975. This second edition, now titled Theodore Dreiser: A Primary Bibliography and Reference Guide, again seeks to provide a comprehensive bibliography of Dreiser's publications and of writing about him.