On the Interpretation of Aspect and Tense in Chiyao, Chiche'a and English

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Phonlab Annual Report

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley PhonLab Annual Report Title The Natural History of Verb-stem Reduplication in Bantu Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9ws0p3sx Journal UC Berkeley PhonLab Annual Report, 4(4) ISSN 2768-5047 Author Hyman, Larry M Publication Date 2008 DOI 10.5070/P79ws0p3sx eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UC Berkeley Phonology Lab Annual Report (2008) Submitted to Proceedings of 2nd Graz Conference on Reduplication, January 2008 The Natural History of Verb-Stem Reduplication in Bantu Larry M. Hyman University of California, Berkeley ABSTRACT In this study I present a comparative and historical analysis of “frequentative” Bantu verb-stem reduplication, many of whose variants have been described for a number of Eastern and Southern Bantu languages. While some languages have full-stem compounding, where the stem consists of the verb root plus any and all suffixes, others restrict the reduplicant to two syllables. Two questions are addressed: (i) What was the original nature of reduplication in Proto-Bantu? (ii) What diachronic processes have led to the observed variation? I first consider evidence that the frequentative began as full-stem reduplication, which then became restricted either morphologically (by excluding inflectional and ultimately derivational suffixes) and/or phonologically (by imposing a bisyllabic maximum size constraint). I then turn to the opposite hypothesis and consider evidence and motivations for a conflicting tendency to rebuild full-stem reduplication from the partial reduplicant. I end by attempting to explain why the partial reduplicant is almost always preposed to the fuller base. 1. Introduction As Ashton (1944:316) succinctly puts it, “REDUPLICATION is a characteristic of Bantu languages. -

Chapter 1 Negation in a Cross-Linguistic Perspective

Chapter 1 Negation in a cross-linguistic perspective 0. Chapter summary This chapter introduces the empirical scope of our study on the expression and interpretation of negation in natural language. We start with some background notions on negation in logic and language, and continue with a discussion of more linguistic issues concerning negation at the syntax-semantics interface. We zoom in on cross- linguistic variation, both in a synchronic perspective (typology) and in a diachronic perspective (language change). Besides expressions of propositional negation, this book analyzes the form and interpretation of indefinites in the scope of negation. This raises the issue of negative polarity and its relation to negative concord. We present the main facts, criteria, and proposals developed in the literature on this topic. The chapter closes with an overview of the book. We use Optimality Theory to account for the syntax and semantics of negation in a cross-linguistic perspective. This theoretical framework is introduced in Chapter 2. 1 Negation in logic and language The main aim of this book is to provide an account of the patterns of negation we find in natural language. The expression and interpretation of negation in natural language has long fascinated philosophers, logicians, and linguists. Horn’s (1989) Natural history of negation opens with the following statement: “All human systems of communication contain a representation of negation. No animal communication system includes negative utterances, and consequently, none possesses a means for assigning truth value, for lying, for irony, or for coping with false or contradictory statements.” A bit further on the first page, Horn states: “Despite the simplicity of the one-place connective of propositional logic ( ¬p is true if and only if p is not true) and of the laws of inference in which it participate (e.g. -

1 Aspect Marking and Modality in Child Vietnamese

1 Aspect Marking and Modality in Child Vietnamese Jennie Tran and Kamil Deen University of Hawai‛i at Mānoa This paper examines the acquisition of aspect morphology in the naturalistic speech of a Vietnamese child, aged 1;9. It shows that while the omission of aspect markers is the predominant error, errors of commission are somewhat more frequent than expected (~20%). Errors of commission are thought to be exceedingly rare in child speech (<4%, Sano & Hyams, 1994), and thus it appears as if these errors in child Vietnamese are more common than in other languages. They occur exclusively with perfective markers in modal contexts, i.e., perfective markers occur with non-perfective, but modal interpretation. We propose, following Hyams (2002), that these errors are permitted by the child’s grammar since perfective features license mood. Additional evidence from the corpus shows that all the perfective-marked verbs in modal context are eventive verbs. We thus further propose that the corollary to RIs in Vietnamese is perfective verbs in modal contexts. 1. INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND There has been considerable debate regarding the acquisition of tense and aspect by young children. Studies on the acquisition of tense-aspect morphology have either attempted to make a general distinction between tense and aspect, or the more specific distinction between grammatical and lexical aspect, or they have centered their analyses around Vendler’s (1967) four-way classification of the inherent semantics of verbs: achievement, accomplishment, activity, and state. The majority of the studies have concluded that the use of tense and aspect inflectional morphology is initially restricted to certain semantic classes of verbs (Bronkard and Sinclair 1973, Antinucci and Miller 1976, Bloom et al. -

Hyman Underlying Bantu Segmental Phonology PLAR

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley PhonLab Annual Report Title Underlying Representations and Bantu Segmental Phonology Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7c47r652 Journal UC Berkeley PhonLab Annual Report, 12(1) ISSN 2768-5047 Author Hyman, Larry M. Publication Date 2016 DOI 10.5070/P7121040729 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UC Berkeley Phonetics and Phonology Lab Annual Report (2016) Underlying Representations and Bantu Segmental Phonology Larry M. Hyman University of California, Berkeley 1. Introduction1 Within recent phonological work, there has been a recurrent move away from underlying representations (URs) as being distinct from what one encounters on the “surface”, sometimes quite dramatic: ... the notion of UR is neither conceptually necessary nor empirically supported, and should be dispensed with. (Burzio 1996: 118) ... we will argue against the postulation of “a single underlying representation per morpheme”, arguing instead for the postulation of a set of interconnected surface-based representations. (Archangeli & Pulleyblank 2015) For decades the assumption in traditional phonology has been that URs had the two functions of (i) capturing generalizations (“what’s in the language”) and (ii) capturing the speaker’s knowledge (“what’s in the head”). Bantu languages have been among those providing evidence of robust morphophonemic alternations of the sort captured by URs in generative phonology. In this paper I take a new look at some Bantu consonant alternations to ask whether URs are doing the effective job we have assumed. As I enumerated in Hyman (2015), various phoneticians and phonologists have expressed skepticism towards URs for one or more of the following reasons: (1) a. -

Corpus Study of Tense, Aspect, and Modality in Diglossic Speech in Cairene Arabic

CORPUS STUDY OF TENSE, ASPECT, AND MODALITY IN DIGLOSSIC SPEECH IN CAIRENE ARABIC BY OLA AHMED MOSHREF DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2012 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Elabbas Benmamoun, Chair Professor Eyamba Bokamba Professor Rakesh M. Bhatt Assistant Professor Marina Terkourafi ABSTRACT Morpho-syntactic features of Modern Standard Arabic mix intricately with those of Egyptian Colloquial Arabic in ordinary speech. I study the lexical, phonological and syntactic features of verb phrase morphemes and constituents in different tenses, aspects, moods. A corpus of over 3000 phrases was collected from religious, political/economic and sports interviews on four Egyptian satellite TV channels. The computational analysis of the data shows that systematic and content morphemes from both varieties of Arabic combine in principled ways. Syntactic considerations play a critical role with regard to the frequency and direction of code-switching between the negative marker, subject, or complement on one hand and the verb on the other. Morph-syntactic constraints regulate different types of discourse but more formal topics may exhibit more mixing between Colloquial aspect or future markers and Standard verbs. ii To the One Arab Dream that will come true inshaa’ Allah! عربية أنا.. أميت دمها خري الدماء.. كما يقول أيب الشاعر العراقي: بدر شاكر السياب Arab I am.. My nation’s blood is the finest.. As my father says Iraqi Poet: Badr Shaker Elsayyab iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I’m sincerely thankful to my advisor Prof. Elabbas Benmamoun, who during the six years of my study at UIUC was always kind, caring and supportive on the personal and academic levels. -

Markedness in Universal Grammar and Second Language Acquisition

Aug. 2006, Volume 3, No.8 (Serial No.21) US-China Education Review, ISSN1548-6613, USA Markedness in Universal Grammar and Second Language Acquisition JIANG Zhao-zi, SHAO Chang-zhong (Linyi Normal University, Linyi, Shandong 276005, P. R. China) Abstract: This paper focuses on the study of markedness theory in Universal Grammar (UG) and its implications in Second Language Acquisition (SLA), showing that the language learners should consciously compare and contrast the similarities and differences between his native language and target language, which will facilitate their learning. Key words: markedness; Universal Grammar; language learning 1. Introduction The term of “markedness” was first proposed by N.S.Trubetzkoy, a leading linguist in Prague School, in his book The Principles of Phonology. At first it was confined to phonetics: in a pair of opposite phonemes, one is characterized as marked, while the other one lacks such markedness. Now it has been widely applied to the researches on phonetics, grammars, semantics, pragmatics, psychological linguistics and applied injustices. The term markedness can be divided into three classes: formal markedness, distribution markedness and semantic markedness (WANG Ke-fei, 1991). 2. Theoretical Researches on Markedness The term “marked” has been defined in different ways. The most underlying one among the definitions is the notion that some linguistic features are “special” in relation to others, which are more “basic”. More technical definitions of “marked” can be found in different linguistics traditions. 2.1 Language-typology-based definition The identification of typological universals has been used to make claims about which features are marked and which one is unmarked. -

Aspectual Forms in Lutsotso

Languages Research Journal in Modern Languages and Literatures https://royalliteglobal.com/languages-and-literatures & Literatures Research Article Section: Literature, Languages and Criticism This article is published Aspectual forms in Lutsotso by Royallite Global, Kenya in the Research Journal in Modern Languages and Hellen Odera¹ & David Barasa² Literatures, Volume 2, Issue ¹-²Department of Languages and Literature Education, 2, 2021 Masinde Muliro University of Science and Technology, Kenya Article Information Correspondence: [email protected] Submitted: 15th Jan 2021 Accepted: 30th Mar 2021 Published: 5th April 2021 Abstract This paper analyses the inflectional category of aspect in Additional information is Lutsotso, a dialect of the Oluluhya macro-language. Using available at the end of the descriptive approach, the paper establishes that there are article a number of inflectional morphemes affixed on the verb https://creativecommons. root to express, e.g. person, number, tense, aspect and org/licenses/by/4.0/ mood. Among these affixes, tense and aspect categories interact largely, hence, it is difficult to study one category To read the paper without referring to the other. While tense and aspect are online, please scan this profoundly connected in Lutsotso, this paper only identifies QR code and describes the inflectional form of aspect. Generally, aspect in Lutsotso relates to the grammatical viewpoints such as the perfective, imperfective and iterative forms. This includes the temporal properties of situations and the situation types as well. Aspect just like other grammatical categories such as tense, mood, person, agreement and number are important in understanding the grammar of Lutsotso. Keywords: aspect, Bantu, Lutsotso verb How to Cite: Public Interest Statement Odera, H., & Barasa, D. -

1. Introduction 1. Malawi: a Multi-Ethnic Nation

From: Dr. Willie Zeze RE: Abstract Submission – 2015 Religious Freedom and Religious Pluralism in Africa: Prospects and Limitations Conference DEMOCRATIC CONSTITUTION AND ETHNIC ORGANIZATIONS IN MALAWI - PRESERVING GOOD TRADITIONAL PRACTICES OR PROMOTING NEPOTISM AND TRIBALISM? Abstract Due to the advent of the 1994 democratic constitution particularly its enactment on Protection of human rights and freedoms: Culture and language, Freedom of association, Religion and beliefs, Freedom of assembly and Political rights, Malawi has witnessed mushrooming of tribal organizations, aiming at preserving the traditional African religious beliefs and African cultural traditions. The Chewa Heritage Foundation (Chefo) and the Muhlakho wa Alhomwe (MWA) among the Chewa and Lhomwe tribes respectively are among well-known ethnic organizations through which the traditional beliefs, cultural traditions and religions are enjoying a significant respect from members of mentioned-tribes. The democratic constitution has cleared a road for the establishment of these ethnic organizations. However, it seems activities of Chefo and MWA are inter alia promoting tribalism and nepotism, in addition to being used as campaign tools for some political parties. This article intends to assess and evaluate the role and the impact of the Chefo and MWA on preservation of good cultural practices and constitutional democracy in Malawi. The hypothesis is, in spite of preserving cultural practices as guaranteed in constitution, the tribal organizations need to be watchful so that they should not promote tribalism, nepotism and being used as campaign tools by Malawian politicians. 1. Introduction In order to appreciate how in their understanding the Democratic Constitution the Chewa Heritage Foundation and Mulhako wa Alhomwe in Malawi, revitalize, preserved and protect customs, values, beliefs and traditional practices it is necessary to understand a social- political history of Malawi. -

Catalogue 97

Eastern Africa A catalogue of books concerning the countries of Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Rwanda, Burundi, and Malawi. Catalogue 97 London: Michael Graves-Johnston, 2007 Michael Graves-Johnston 54, Stockwell Park Road, LONDON SW9 0DA Tel: 020 - 7274 – 2069 Fax: 020 - 7738 – 3747 Website: www.Graves-Johnston.com Email: [email protected] Eastern Africa: Catalogue 97. Published by Michael Graves-Johnston, London: 2007. VAT Reg.No. GB 238 2333 72 ISBN 978-0-9554227-1-3 Price: £ 5.00 All goods remain the property of the seller until paid for in full. All prices are net and forwarding is extra. All books are in very good condition, in the publishers’ original cloth binding, and are First Editions, unless specifically stated otherwise. Any book may be returned if unsatisfactory, provided we are advised in advance. Your attention is drawn to your rights as a consumer under the Consumer Protection (Distance Selling) Regulations 2000. The illustrations in the text are taken from item 49: Cott: Uganda in Black and White. The cover photograph is taken from item 299: Photographs. East Africa. Eastern Africa 1. A Guide to Zanzibar: A detailed account of Zanzibar Town and Island, including general information about the Protectorate, and a description of Itineraries for the use of visitors. Zanzibar: Printed by the Government Printer, 1952 Wrpps, Cr.8vo. xiv,146pp. + 18pp. advertisements, 4 maps, biblio., appendices, index. Slight wear to spine, a very nice copy in the publisher’s pink wrappers. £ 15.00 2. A Plan for the Mechanized Production of Groundnuts in East and Central Africa. Presented by the Minister of Food to Parliament by Command of His Majesty February, 1947. -

Markedness in Distributed Morphology

Markedness in Distributed Morphology Philipp Weisser [email protected] 08.03.2018 1 Introduction The concept of morphological markedness goes back at least to the works of Jakob- son and Trubetskoy in the 1930s and since then the term markedness has developed a wide range of possible senses.1 This is arguably due to the fact that the concept itself has proven helpful in a lot of different areas of linguistic research and has thus been adopted by different groups of researchers with different research foci. Unsurprisingly, a term with such a great number of possible interpretations can lead to confusion in a research community which strives for concreteness and sci- entific accuracy. This lead to a number of different attempts to define the concept of markedness in a scientific fashion or classify the different meanings of the term (see e.g. Moravcsik and Wirth 1986; Dixon 1994; Battistella 1990; Haspelmath 2006). In what follows, I will add one more paper to this list which has a much narrower focus than the ones above as it only addresses the notions of the term marked- ness relevant in the context of the framework of Distributed Morphology (Halle and Marantz 1993, 1994; Halle 1997). The literature on Distributed Morphology is not an exception in that the term markedness is also used for a number of related but still fundamentally different concepts. One of the goals of this paper is thus to try to shed some light on the different uses of the term markedness, how they relate and what the general expec- tations of the theory are as to whether different notions of markedness are supposed to pattern together or not. -

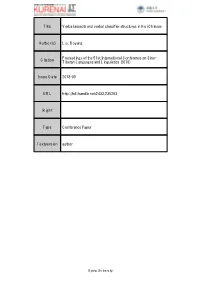

Title Verbal Aspects and Verbal Classifier Structures in Hui Chinese

Title Verbal aspects and verbal classifier structures in Hui Chinese Author(s) Liu, Boyang Proceedings of the 51st International Conference on Sino- Citation Tibetan Languages and Linguistics (2018) Issue Date 2018-09 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/235293 Right Type Conference Paper Textversion author Kyoto University Verbal Aspects and Verbal Classifier Structures in Hui Chinese LIU Boyang (EHESS-CRLAO) CONTENT • PART I: Research Purpose • PART II: The definition and classification of VCLs in Sinitic languages – 1. An introduction to Hui Chinese – 2. Previous work on VCLs in Mandarin – 3. A provisional definition and classification of VCLs in Sinitic languages – 4. Lexical aspects indicated by the verb phrase [VERB-VCLP] in Sinitic languages – 5. Relationships between grammatical aspects and the verb phrase [VERB-VCLP- OBJECT] • PART III: Grammatical aspects indicated by special auto-verbal classifier (Auto-VCL) structures in Hui Chinese – 6. The perfective aspect – 7. The imperfective aspect • PART IV: Conclusion PART I: RESEARCH PURPOSE Research Purpose: • Verbal classifiers (VCLs) have been much less studied from a typological perspective than the category of nominal classifiers (NCLs), and even less in the non-Mandarin branches of Sinitic languages, such as the Hui dialects; • In this study, I will introduce relationships between lexical aspects, grammatical aspects and verbal classifier phrases (VCLPs) in Hui Chinese, analyzing the similarities and differences with Standard Mandarin. • Verbal classifier structures in the Hui dialects display a transitional feature compared with Xiang, Gan and Wu, taking auto-verbal classifier (Auto-VCL) structures as examples (auto-VCLs derive from verb reduplicants in the verb phrase [VERB- (‘one’)-VERB]): – Auto-VCLs in the verb phrase [VERB-AUTO VCL] can code the perfective or imperfective aspect in different types of complex sentences in Hui Chinese; – More variety of auto-VCL structures is found in Hui Chinese compared with Xiang and Gan dialects. -

[.35 **Natural Language Processing Class Here Computational Linguistics See Manual at 006.35 Vs

006 006 006 DeweyiDecimaliClassification006 006 [.35 **Natural language processing Class here computational linguistics See Manual at 006.35 vs. 410.285 *Use notation 019 from Table 1 as modified at 004.019 400 DeweyiDecimaliClassification 400 400 DeweyiDecimali400Classification Language 400 [400 [400 *‡Language Class here interdisciplinary works on language and literature For literature, see 800; for rhetoric, see 808. For the language of a specific discipline or subject, see the discipline or subject, plus notation 014 from Table 1, e.g., language of science 501.4 (Option A: To give local emphasis or a shorter number to a specific language, class in 410, where full instructions appear (Option B: To give local emphasis or a shorter number to a specific language, place before 420 through use of a letter or other symbol. Full instructions appear under 420–490) 400 DeweyiDecimali400Classification Language 400 SUMMARY [401–409 Standard subdivisions and bilingualism [410 Linguistics [420 English and Old English (Anglo-Saxon) [430 German and related languages [440 French and related Romance languages [450 Italian, Dalmatian, Romanian, Rhaetian, Sardinian, Corsican [460 Spanish, Portuguese, Galician [470 Latin and related Italic languages [480 Classical Greek and related Hellenic languages [490 Other languages 401 DeweyiDecimali401Classification Language 401 [401 *‡Philosophy and theory See Manual at 401 vs. 121.68, 149.94, 410.1 401 DeweyiDecimali401Classification Language 401 [.3 *‡International languages Class here universal languages; general