The Lion in Winter the Articles in This Study Guide Are Not Meant to Mirror Or Interpret Any Productions at the Utah Shakespeare Festival

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PDF of the Princess Bride

THE PRINCESS BRIDE S. Morgenstern's Classic Tale of True Love and High Adventure The 'good parts' version abridged by WILLIAM GOLDMAN one two three four five six seven eight map For Hiram Haydn THE PRINCESS BRIDE This is my favorite book in all the world, though I have never read it. How is such a thing possible? I'll do my best to explain. As a child, I had simply no interest in books. I hated reading, I was very bad at it, and besides, how could you take the time to read when there were games that shrieked for playing? Basketball, baseball, marbles—I could never get enough. I wasn't even good at them, but give me a football and an empty playground and I could invent last-second triumphs that would bring tears to your eyes. School was torture. Miss Roginski, who was my teacher for the third through fifth grades, would have meeting after meeting with my mother. "I don't feel Billy is perhaps extending himself quite as much as he might." Or, "When we test him, Billy does really exceptionally well, considering his class standing." Or, most often, "I don't know, Mrs. Goldman; what are we going to do about Billy?" What are we going to do about Billy? That was the phrase that haunted me those first ten years. I pretended not to care, but secretly I was petrified. Everyone and everything was passing me by. I had no real friends, no single person who shared an equal interest in all games. -

Inventory Acc.13182 Edith Macarthur

Acc.13182 October 2010 Inventory Acc.13182 Edith Macarthur National Library of Scotland Manuscripts Division George IV Bridge Edinburgh EH1 1EW Tel: 0131-466 2812 Fax: 0131-466 2811 E-mail: [email protected] © Trustees of the National Library of Scotland Papers, circa 1942-2006, of Edith Macarthur, actor (b.1926). The collection includes scripts, photographs, press cuttings and other items of theatre and television memorabilia. Edith Macarthur’s stage career has taken her to most major producing theatres in Scotland, and to many in England. The variety of her range is demonstrated in the collection, from her early days with respected amateur company, the Ardrossan and Saltcoats Players, to acclaim with prestigious companies such as the Royal Lyceum, Citizens’, Gateway, Bristol Old Vic, Pitlochry Festival, Traverse and Royal Shakespeare. Leading roles in the canon of major plays by Arthur Miller, James Bridie, Anton Chekhov, Eugene O’Neill, Noel Coward and their like, and various acclaimed productions of ‘The Thrie Estaites’, established her stage reputation. Alongside runs a vein of comedy and variety, from the ‘Five Past Eight Shows’ of the 1950s at the Citizens’, to regularly playing Cinderella’s Fairy Godmother in pantomime during the 1980s and 1990s. There is also a considerable body of television work, from early series such as ‘The Borderers’ and ‘Sutherland’s Law’, and the renowned 1970s adaptation of ‘Sunset Song’, to the long-running Scottish Television soap, ‘High Road’. A milestone was the 1993 film ‘The Long Roads’ by John McGrath. At about this time Miss Macarthur was coming to the attention of less mainstream theatre-producers in Scotland. -

The Lion in Winter

NOW ON STAGE: THE LION IN WINTER WRITERS’ THEATRE THE BRIEF CHRONICLE ISSUE TWENTY-ONE MAY 2008 13 Nixon’s Nixon returns to Writers’ Theatre for a limited engagement! 14 Shannon Cochran & Michael Canavan work as a husband and wife team in The Lion in Winter. 24 Writers’ Theatre celebrated its annual WordPlay Gala at The Peninsula Chicago. $2.00 HAVE YOU RENEWED YET? 05 ON stagE: THE LION IN WINTER 06 THE GOLDMAN YEARS 09 HENRY AND ELEANOR 13 NIXON’S NIXON 14 ARTISTIC CONVERsatION 19 FAMIly: A CAST OF CHARACTERS BACKstage: 22 EDUCATION 24 GALA WRAP UP 28 SPONSOR SALUTE 29 TOURS 31 PERFORMANCE SCHEDULE 32 IN BRIEF Kevin Asselin and Ross Lehman, As You Like It, 2008 Renew your season tickets today to ensure that you don’t miss the next issue of The Brief Chronicle! The Brief Chronicle, your look into the productions, events and programming at Writers' Theatre, is provided free with all season packages. Make sure to renew your season tickets to continue to receive your insider’s magazine and the rest of the benefits that you are entitled to as a season ticket holder. 847-242-6000 | writerstheatre.org 2 BACH AT LEIPZIG Call 847-242-6000 to renew today! THE 2008/09 SEASON! THE BRIEF CHRONICLE ISSUE TWENTY-ONE MAY 2008 PICNIC By William Inge Directed by David Cromer Michael Halberstam Kathryn M. Lipuma September 16 – November 16, 2008 Artistic Director Executive Director EDITOR THE MAIDS Kory P. Kelly By Jean Genet Director of Marketing & Communications Translated by Martin Crimp Directed by Jimmy McDermott THE BRIEF chronicLE TEAM November 18, 2008 – April 5, 2009 Mica Cole Jon Faris WORLD PREMIERE! Director of Education General Manager Sherre Jennings Cullen Jimmy McDermott OLD GLORY Director of Development Artistic Associate By Brett Neveu Directed by William Brown Kellie de Leon Sara M. -

Audio Described Performances Nov 17 – May 18

Audio Described Performances Nov 17 – May 18 Follies book by James Goldman, music and lyrics by Stephen Sondheim Saturday 16 December at 2pm with a Touch Tour at 12 noon. Beginning by David Eldridge Friday 10 November at 7.30pm Saturday 11 November at 2.30 pm with a touch tour at 1pm. Saint George and the Dragon by Rory Mullarkey Friday 1 December at 7.30pm Saturday 2 December at 2pm with a touch tour at 12.30pm. Barber Shop Chronicles by Inua Ellams Saturday 9 December at 2pm with a touch tour at 12.30pm. Pinocchio by Dennis Kelly with songs and score from the Walt Disney film by Leigh Harline, Ned Washington and Paul J Smith adapted by Martin Lowe Saturday 27 January at 2pm with a touch tour at 12 noon, Monday 29 January at 1pm, Friday 16 February at 7pm Saturday 17 February at 2pm with a touch tour at 12 noon Friday 16 February at 7pm Saturday 17 February at 2pm with a touch tour at 12 noon Network adapted by Lee Hall based on the Paddy Chayefsky film Friday 2 February at 7.30pm, Saturday 3 February at 2pm, with a touch tour at 12 noon Saturday 10 March at 2pm, with a touch tour at 12 noon Foodwork. See Network from a completely unique perspective – on stage – with the immersive dining experience. Access tickets for on-stage seats are £75; this includes a three-course set menu, glass of wine and aperitif. Contact box office for more information. Amadeus by Peter Shaffer Friday 9 February, 7.30pm Saturday 10 February at 2pm with a Touch Tour at 12 noon. -

Ruth Prawer Jhabvala's Adapted Screenplays

Absorbing the Worlds of Others: Ruth Prawer Jhabvala’s Adapted Screenplays By Laura Fryer Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of a PhD degree at De Montfort University, Leicester. Funded by Midlands 3 Cities and the Arts and Humanities Research Council. June 2020 i Abstract Despite being a prolific and well-decorated adapter and screenwriter, the screenplays of Ruth Prawer Jhabvala are largely overlooked in adaptation studies. This is likely, in part, because her life and career are characterised by the paradox of being an outsider on the inside: whether that be as a European writing in and about India, as a novelist in film or as a woman in industry. The aims of this thesis are threefold: to explore the reasons behind her neglect in criticism, to uncover her contributions to the film adaptations she worked on and to draw together the fields of screenwriting and adaptation studies. Surveying both existing academic studies in film history, screenwriting and adaptation in Chapter 1 -- as well as publicity materials in Chapter 2 -- reveals that screenwriting in general is on the periphery of considerations of film authorship. In Chapter 2, I employ Sandra Gilbert’s and Susan Gubar’s notions of ‘the madwoman in the attic’ and ‘the angel in the house’ to portrayals of screenwriters, arguing that Jhabvala purposely cultivates an impression of herself as the latter -- a submissive screenwriter, of no threat to patriarchal or directorial power -- to protect herself from any negative attention as the former. However, the archival materials examined in Chapter 3 which include screenplay drafts, reveal her to have made significant contributions to problem-solving, characterisation and tone. -

Stetson University Theatre Arts Opens Season with Royal Comedy-Drama ‘The Lion in Winter’

Find more news from Stetson University at Stetson Today. FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Stetson University Theatre Arts Opens Season with Royal Comedy-Drama ‘The Lion in Winter’ DELAND, Florida, Sept. 30, 2019 – Stetson Theatre Arts begins its 114th season with James Goldman’s classic play “The Lion in Winter,” directed by Anthony Garcia. The comedy-drama is a tale of royalty, sibling rivalry and adultery, and will run from Oct. 10-13 at Stetson University’s Second Stage Theatre in the Museum of Art – DeLand. “The Lion in Winter,” which was adapted into the 1968 film, starring Katharine Hepburn and Peter O’Toole, tells the story of the Plantagenet family, who are locked in a free-for-all of competing ambitions to inherit a kingdom. In this play, King Henry II of England; his wife Eleanor of Aquitaine; sons Richard the Lionheart, Geoffrey and John; and King Philip II of France and his sister, Alais, render an articulate, witty and darkly comic view of dysfunctional, medieval royal families. It is a modern-day classic you don’t want to miss. “As ‘The Lion in Winter’ demonstrates, the remarkable thing isn’t that family battles continue year after year, but rather that we keep coming home to re-engage,” explained Garcia. “Despite its tragic nature, Goldman’s play brilliantly captures the dark comedy in this situation. While these characters are raising glasses with their right hands, they are secretly clutching daggers in their left hands.” Experience the dramatic intrigue as these members of the royal family scheme their way to the top. -

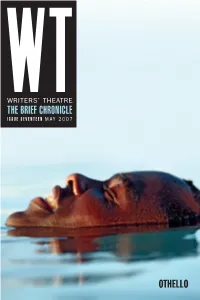

The Brief Chronicle Othello

WRITERS’ THEATRE THE BRIEF CHRONICLE I S S U E SEVENTEEN MAY 2 0 0 7 1 BACH AT LEIPZIG OTHELLO Michael Halberstam Artistic Director Kathryn M. Lipuma Executive Director 0 3 ON STAGE: OTHELLO 04 ARTISTIC CONVERSATION Dear Friends: 08 DIRECTOR’S SIDEBAR 09 THE PLAYERS ON SHAKESPEARE We are delighted to welcome Shakespeare back to Writers’ Theatre after an absence of 1 3 AFRICANS IN ELIZABETHAN ENGLAND 15 FROM PAGE TO STAGE almost a decade. As we go to print with this magazine, we are two weeks into rehearsal for BACKSTAGE: 18 EDUCATION 19 DONOR SPOTLIGHT 20 EVENTS 24 DIRECTOR’S SOCIETY Othello and what a remarkable journey it is proving to be. Shakespeare’s plays are overflowing 2 5 2007/08 SEASON 26 CELEBRATING 15 YEARS 31 IN BRIEF 32 IN MEMORIAM with humanity and every moment of every play involves making a series of specific choices that chart the psychological journey of his text. The result is a wonderfully accessible and recognizable cast of characters who find themselves in extreme circumstances while making fascinating decisions. We can hardly wait to share this production with you! Thank you for being with us over the course of this most exciting 15th Anniversary Season. We are looking forward to bringing you a most wonderful lineup next year! Although we have premiered many adaptations and a number of regional premieres, The Savannah Disputation, which launches the season in September, is our first world premiere play. Evan Smith, the author of The Uneasy Chair, has drawn a delicious look at a conflict between faith and understanding. -

The WKNO-TV Collection

The Theatre Memphis Programs Collection Processed by Joan Cannon 2007 Memphis and Shelby County Room Memphis Public Library and Information Center 3030 Poplar Avenue Memphis, Tennessee 38111 Scope and Content The Theatre Memphis Programs Collection was donated to the Memphis Public Library and Information Center by many individual donors over several years. Consisting of programs from performances at Theatre Memphis between the years 1975 and 2007, the collection provides invaluable information on the operation of community theatre in Memphis. Each program includes the names of the director, cast and crew as well as information on the production. Theatre Memphis was established as the Little Theatre in 1921. For several years plays were performed in a variety of locations in Memphis including Germania Hall and the Nineteenth Century Club. In 1929 the Little Theatre was headquartered at the Pink Palace Museum Playhouse where they would remain until the mid-1970s. When the Pink Palace closed for renovations, the theatrical company opened their own venue on Perkins Extended in East Memphis. Changing their name to Theatre Memphis, productions resumed in 1975 and have continued until the present day. 2 THEATRE MEMPHIS PROGRAMS COLLECTION BOX 1 Folder 1 Items 6 1975-1976 (56th Season) SUNSHINE BOYS by Neil Simon. Directed by Sherwood Lohrey. Cast: Archie S. Grinalds, Jerry Chipman, Ed Cook, Frank B. Crumbaugh, III, Andy Shenk, James Brock, Holly Shelton, Patricia Gill, Sam Stock. n.d. DESIRE UNDER THE ELMS by Eugene O’Neill. Directed by Sherwood Lohrey. Cast: Jay Ehrlicher, Don Barber, Carl Bogan, John Malloy, Janie Paris, Merle Ray, Ralph Brown. -

A-061 Louisiana Tech University, Tech Theater Players Scrapbook

Louisiana Tech University Louisiana Tech Digital Commons University Archives Finding Aids University Archives 2019 A-061 Louisiana Tech University, Tech Theater Players Scrapbook, 1941-1974 University Archives and Special Collections, Prescott eM morial Library, Louisiana Tech University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.latech.edu/archives-finding-aids Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Louisiana Tech University, Tech Theater Players Scrapbook, A-061, Box Number, Folder Number, Department of University Archives and Special Collections, Prescott eM morial Library, Louisiana Tech University, Ruston, Louisiana This Finding Aid is brought to you for free and open access by the University Archives at Louisiana Tech Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Archives Finding Aids by an authorized administrator of Louisiana Tech Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A-061-1 A-061 LOUISIANA TECH UNIVERSITY, TECH THEATER PLAYERS SCRAPBOOK, 1941-1974. SCOPE AND CONTENT The Tech Theater Players was founded in 1926 by Miss Vera Alice Paul. It is one of the oldest student organizations on campus today. 1 scrapbook. DESCRIPTION THE IMPORTANCE OF BEING EARNEST, by Oscar Wilde, November 1941 Director: Vera Alice Paul Cast: Jess Harris, James Files, John Moody, Edward Clark, Richard Slay, Mary Walker, Edna Earle Carroll, Elayne Odom, and Byrd Rawls. MURDER IN THE CATHEDRAL, by T.S. Eliot, March - April 1942 Director: [not found] Cast: [not found] CHARLIE'S AUNT, by Brandon Thomas, October 1944 Director: Vera Alice Paul Cast: Edward Kemp, Charles L. Baxter, Billy Moreland, W. -

Sunset Playhouse Production History 2020-21 Season Run for Your Wife

Sunset Playhouse Production History 2020-21 Season Run for your Wife by Ray Cooney presented by special arrangement with Concord Theatricals for Samuel French 9 to 5, The Musical by Dolly Parton presented by special arrangement with MTI Elf by Thomas Meehan & Bob Martin presented by special arrangement with MTI 4 Weddings and an Elvis by Nancy Frick presented by special arrangement with Concord Theatricals for Samuel French The Cemetery Club by Ivan Menchell presented by special arrangement with Concord Theatricals for Samuel French Young Frankenstein by Mel Brooks presented by special arrangement with MTI An Inspector Calls by JB Priestley presented by special arrangement with Concord Theatricals for Samuel French Newsies by Harvey Fierstein presented by special arrangement with MTI _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ 2019-2020 Season A Comedy of Tenors – by Ken Ludwig presented by special arrangement with Samuel French Mamma Mia – presented by special arrangement with MTI The Game’s Afoot – by Ken Ludwig presented by special arrangement with Samuel French The Marvelous Wonderettes – by Roger Bean presented by special arrangement with StageRights, Inc. Noises Off – by Michael Frayn presented by special arrangement with Samuel French Cabaret – by Joe Masteroff presented by special arrangement with Tams-Witmark Barefoot in the Park – by Neil Simon presented by special arrangement with Samuel French (cancelled due to COVID 19) West Side Story – by Jerome Robbins presented by special arrangement with MTI (cancelled due to COVID 19) 2018-2019 Season The Man Who Came To Dinner – by Moss Hart and George S. Kaufman presented by special arrangement with Dramatists Play Mary Poppins - Original Music and Lyrics by Richard M. -

2000 MFA, Scenic Design, Yale School of Drama 1995 BS, Theater

Pace University office: 212-618-6106 www.lukecantarella.com 140 William Street #606 mobile: 646-263-4989 e-mail: [email protected] New York, NY 10038 or [email protected] education: 2000 M.F.A., Scenic Design, Yale School of Drama 1995 B.S., Theater, Northwestern University other training: School of the Art Institute, Art Students League, The Drawing Center, Columbia University (Summer Intensive in German) university experience: 2012-present Associate Professor/Pace University Head of Set Design (2013-2016): Responsibilities include undergraduate teaching, course development, mentoring student designers, 1st year student advisement Head of Production and Design (2012-2013): Responsibilities include undergraduate teaching, establishing a curriculum for new BFA program in Production & Design, recruiting and retaining students, hiring and mentoring new faculty, student mentorship, production planning and budgeting. 2008-12 Associate Professor/University of California, Irvine Head of Set Design Program: Responsibilities include teaching both graduate and undergraduate courses, curriculum design, recruiting and retaining students, mentorship, thesis reviews, production planning and budgeting. Tenure granted: June 2012 scenic design projects: For the following projects (plays, musicals, dances & live performance), I was in charge of designing the scenery. Responsibilities included collaborating with directors, playwrights, choreographers and other designer to analyze a text, forming design ideas, researching of visual culture, creating design documents (sketches, models, technical drawings, etc.), specifying paint colors and finishes, and the supervising assistants and fabricators including painters, carpenters, masons, furniture-makers, upholsterers and properties masters. Projects listed below show the name of the play, name of the playwright, name of the director and theater or producer. Productions in bold indicate world premieres. -

Guide to the Presbyterian Players Collection

Guide to IU South Bend Presbyterian Players Collection Summary Information Repository: Indiana University South Bend Archives 1700 Mishawaka Avenue P.O. Box 7111 South Bend, Indiana 46634 Phone: (574) 520-4392 Email: [email protected] Creator: Indiana University South Bend Title: Presbyterian Players Collection Extent: .50 linear ft. Abstract: Often touted as “South Bend’s oldest community theatre,” the Presbyterian Players mounted hundreds of productions over five decades, including familiar plays and popular musicals, as well as the occasional lesser-known work. The group formed in 19451 under the auspices of the First Presbyterian Church of South Bend, Indiana. While some productions took place in venues like the Washington High School Auditorium, the Indiana University South Bend Auditorium, or the Bendix Theatre at the Century Center, the majority of the performances associated with the programs in this collection took place in the Church itself. The First Presbyterian Church has a long history as part of the wider Michiana community. A small group of early South Bend residents came together to form the church in 1834, and as the congregation grew, so too did the structures built to accommodate it. The grandest of these, built in 1889, still stand at the corner of Lafayette and West Washington Streets—though it is no longer the site of the First Presbyterian Church, which has been located on West Colfax Avenue since 1953.2 Sisters Mary Pappas (February 7, 1926–June 11, 2012) and Aphrodite Pappas (c. 1923– ), who donated the materials found in this inventory, directed, acted in, or otherwise helped stage numerous performances of the Presbyterian Players.