The Role of Regional Parliaments in the Process of Subsidiarity Analysis Within the Early Warning System of the Lisbon Treaty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

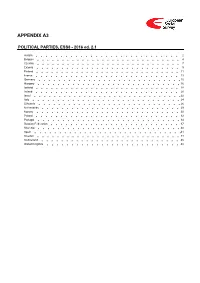

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

Volume 5 Issue 2 2013

VOLUME 5 ISSUE 2 2013 ISSN: 2036-5438 VOL. 5, ISSUE 2, 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS SPECIAL ISSUE Regional Parliaments in the European Union: A comparison between Italy and Spain Edited by Josep M. Castellà Andreu, Eduardo Gianfrancesco, Nicola Lupo and Anna Mastromarino ESSAYS National and Regional Parliaments in the EU decision-making process, after the The Relationship between State and Treaty of Lisbon and the Euro-crisis Regional Legislatures, Starting from the NICOLA LUPO E- 1-28 Early Warning Mechanism CRISTINA FASONE E-122-155 Spanish Autonomous Communities and EU policies State accountability for violations of EU law AGUSTÍN RUIZ ROBLEDO E- 29-50 by Regions: infringement proceedings and the right of recourse The scrutiny of the principle of subsidiarity CRISTINA BERTOLINO E-156-177 by autonomous regional parliaments with particular reference to the participation of the Parliament of Catalonia in the early warning system ESTHER MARTÍN NÚÑEZ E- 51-73 Early warning and regional parliaments: in search of a new model. Suggestions from the Basque experience JOSU OSÉS ABANDO E- 74-88 The evolving role of the Italian Conference system in representing regional interest in EU decision-making ELENA GRIGLIO E- 89-121 ISSN: 2036-5438 National and Regional Parliaments in the EU decision-making process, after the Treaty of Lisbon and the Euro-crisis by Nicola Lupo Perspectives on Federalism, Vol. 5, issue 2, 2013 Except where otherwise noted content on this site is licensed under a Creative Commons 2.5 Italy License E - 1 Abstract The Treaty of Lisbon increased the role of National and Regional Parliaments in the EU decision-making process, in order to compensate for some of the weaknesses of the European institutional architecture. -

Overview of Organizational Developments in Spanish Anti-Revisionism

Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line * Spain Overview of Page | 1 organisational developments First Published: May 2019 Transcription, Editing and Markup: Sam Richards and Paul Saba Copyright: This work is in the Public Domain under the Creative Commons Common Deed. You can freely copy, distribute and display this work; as well as make derivative and commercial works. Please credit the Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line as your source, include the url to this work, and note any of the transcribers, editors & proofreaders above. In 1963 the first anti-revisionists Marxist-Leninist organisations arose, and after that, various others developed either through subsequent splits or by indirect or direct routes, not least the student movement and catholic circles influenced by Marxism. Like elsewhere in Europe, inspired by the Sino-Soviet Polemic and later the Cultural Revolution, there was an organisational rupture, a separation from the revisionist party, but how much of a political, ideological and organisational rupture was there? The proliferation of small militants groups1, and an inability to rally a stable recognised leadership that could command allegiance amongst the various trends saw unresolved ideological concerns engendered criticism and splits that were never resolved in any organisation that could act as, rather than proclaim itself, the successor of the PCE. Spanish anti-revisionists operated under a repressive authoritarian regime headed by Franco whose military coup had overthrown the Spanish republic. It was a heroic struggle in a regime noted for its anti-communist repression and police killing demonstrating workers in the streets, generating an armed response of differing intensity and effectiveness. -

Meeting of the OECD Global Parliamentary Network 1-2 October 2020 List of Participants

as of 02/10/2020 Meeting of the OECD Global Parliamentary Network 1-2 October 2020 List of participants MP or Chamber or Political Party Country Parliamentary First Name Last Name Organisation Job Title Biography (MPs only) Official represented Pr. Ammar Moussi was elected as Member of the Algerian Parliament (APN) for the period 2002-2007. Again, in the year Algerian Parliament and Member of Peace Society 2017 he was elected for the second term and he's now a member of the Finance and Budget commission of the National Algeria Moussi Ammar Parliamentary Assembly Member of Parliament Parliament Movement. MSP Assembly. In addition, he's member of the parliamentary assembly of the Mediterranean PAM and member of the executif of the Mediterranean bureau of tha Arab Renewable Energy Commission AREC. Abdelmajid Dennouni is a Member of Parliament of the National People’s Assembly and a Member of finances and Budget Assemblée populaire Committee, and Vice president of parliamentary assembly of the Mediterranean. He was previously a teacher at Oran Member of nationale and Algeria Abdelmajid Dennouni Member of Parliament University, General Manager of a company and Member of the Council of Competitiveness, as well as Head of the Parliament Parliamentary Assembly organisaon of constucng, public works and hydraulics. of the Mediterranean Member of Assemblée Populaire Algeria Amel Deroua Member of Parliament WPL Ambassador for Algeria Parliament Nationale Assemblée Populaire Algeria Parliamentary official Safia Bousnane Administrator nationale Lucila Crexell is a National Senator of Argentina and was elected by the people of the province of Neuquén in 2013 and reelected in 2019. -

Galego. Language and History

Galego Language and History "Galicia. Fisterra, the western end of the known land. Beyond these rough rocks, there is the Ocean, Gloomy, Sociolinguistic which finishes in big abysses where huge whales status sail, big hostile beasts. Man's habitat finishes here, and everyday he can witness the death of the sun. Galicia is steep mountains, long plains, wide valleys Language policy at the East. Some small sierras come to the sea, which in many parts of the coast goes into land, forming the beautiful "rías", which are so typical in Galicia Ten thousand rivers run along Galician green Laws skin, and if the beech tree grows and the wolf runs at the eastern mountains, the camellia flowers and the lemon and orange trees offer their golden fruits at the western shore". Alvaro Cunqueiro C atalà Euskara Cymraeg Elsässisch Galego Language and History Sociolinguistic status Language policy Laws Galicia is located on the Northwest corner of the Iberian Peninsula. It covers an area of 29,575 square kilometres. Its orography is irregular and the coast is jagged forming the so-called “rías”. The political-administrative capital is Santiago de Compostela. The current administrative division, established in the 19th century, divides the territory into four provinces: A Coruña, Lugo, Ourense and Pontevedra. Galicia has 2, 812,962 inhabitants. By province, the population is distributed as follows: A Coruña 1,131,404; Lugo 387,038; Ourense 362,832 and Pontevedra 931,688. Galician population is distributed irregularly throughout the territory. It’s density is 94.4 inhabitants/km2. Galician population is characterized by a high level of dispersion, with small population centres. -

Redalyc.¿SON LAS TECNOLOGÍAS DE LA INFORMACIÓN CAPACES

Teoría de la Educación. Educación y Cultura en la Sociedad de la Información E-ISSN: 1138-9737 [email protected] Universidad de Salamanca España García Vázquez, Yolanda; Ferrás Sexto, Carlos ¿SON LAS TECNOLOGÍAS DE LA INFORMACIÓN CAPACES DE CAMBIAR LAS FORMAS DE HACER POLÍTICA? ESTUDIO DE CASOS EN GALICIA Teoría de la Educación. Educación y Cultura en la Sociedad de la Información, vol. 10, núm. 2, julio, 2009, pp. 146-164 Universidad de Salamanca Salamanca, España Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=201017352010 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Revista Electrónica Teoría de la Educación. Educación y Cultura en la Sociedad de la Información. http://www.usal.es/teoriaeducacion Vol. 10. Nº 2. Julio 2009 ¿SON LAS TECNOLOGÍAS DE LA INFORMACIÓN CAPACES DE CAMBIAR LAS FORMAS DE HACER POLÍTICA? ESTUDIO DE CASOS EN GALICIA Resumen: En la sociedad industrial los políticos tenían que dominar el lenguaje de la TV pues interesaba más la intensidad de la reacción que la duración del mensaje; debían emplear frases contundentes. En la Sociedad de la Información, con las tecnologías de la comunicación (Tic), esto cambia considerablemente pues la sociedad gana pluralismo y hay más voces que se hacen oír. Aparecen los Blogs como una forma de emitir opi- nión e información, que podemos considerar como una forma de expresión alternativa (aportan visiones diferentes de las noticias, ignoradas por los grandes medios). -

Linguistic and Cultural Crisis in Galicia, Spain

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1991 Linguistic and cultural crisis in Galicia, Spain. Pedro Arias-Gonzalez University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Arias-Gonzalez, Pedro, "Linguistic and cultural crisis in Galicia, Spain." (1991). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 4720. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/4720 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LINGUISTIC AND CULTURAL CRISIS IN GALICIA, SPAIN A Dissertation Presented by PEDRO ARIAS-GONZALEZ Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION May, 1991 Education Copyright by Pedro Arias-Gonzalez 1991 All Rights Reserved LINGUISTIC AND CULTURAL CRISIS IN GALICIA, SPAIN A Dissertation Presented by PEDRO ARIAS-GONZALEZ Approved as to style and content by: DEDICATION I would like to dedicate this dissertation to those who contributed to my well-being and professional endeavors: • My parents, Ervigio Arias-Fernandez and Vicenta Gonzalez-Gonzalez, who, throughout their lives, gave me the support and the inspiration neces¬ sary to aspire to higher aims in hard times. I only wish they could be here today to appreciate the fruits of their labor. • My wife, Maria Concepcion Echeverria-Echecon; my son, Peter Arias-Echeverria; and my daugh¬ ter, Elizabeth M. -

Digitizing Galicia: Cultural Policies and Trends in Cultural Heritage Management

Digitizing Galicia: Cultural Policies and Trends in Cultural Heritage Management Ekaterina Volkova University of Auckland Abstract: Cultural policies have developed in Galicia significantly since the establishment of the 1981 Statute of Galician Autonomy. The Galician government has played a key role in the Galician cultural scene. However, the civil and, especially, private sectors have made a substantial contribution to the promotion of different areas of Galician culture. This arti- cle presents an overview of Galician cultural policies focusing on the area of cultural herit- age management in the global era, particularly on the uses of new information and commu- nication technologies and digitization. Keywords: Cultural policy; cultural heritage; digitization; Xunta de Galicia; Galiciana, Afundación, ABANCA. Galicia dixital: Políticas culturais e tendencias na xestión do legado cultural Resumo: En Galicia, as políticas culturais desenvolvéronse de maneira significativa desde o establecemento do Estatuto de Autonomía de Galicia de 1981. O goberno galego veu xo- gando un papel fundamental na escena cultural. Porén, os sectores civil e, nomeadamente, o privado fixeron contribucións substanciais na promoción de diferentes áreas da cultura galega. Este artigo ofrece unha panorámica das políticas culturais centrándose no ámbito da xestión do legado cultural na era global, particularmente no referente ao emprego das novas tecnoloxías da información e a comunicación e dixitalización. Palavras chave: Política cultural; legado cultural; dixitalización; Xunta de Galicia; Galicia- na, Afundación, ABANCA. «Adiós ríos, adiós fontes; adiós, regatos pequenos; adiós, vista dos meus ollos, non sei cándo nos veremos»—the lines from Cantares Gallegos, a landmark of Galician culture—was displayed on computer screens and smartphones around the world on February 24, 2015. -

The President / Le Président

11 January 2013 CONGRESS MONITORING VISIT TO SPAIN Madrid, 14 January 2012 PROGRAMME Congress delegation Rapporteurs Mr Marc COOLS Co-rapporteur on local democracy Chamber of Local Authorities, ILDG1 Member of the Monitoring Committee of the Congress Alderman of Uccle (Belgium) Mr Leen VERBEEK Co-rapporteur on regional democracy Chamber of Regions, SOC1 Member of the Monitoring Committee of the Congress Queen's Commissioner of the Province of Flevoland (Netherlands) Expert Mr Francesco MERLONI Consultant (Italy) President of the Group of Independent Experts on the European Charter of Local Self-Government of the Congress Congress Secretariat: Ms Stéphanie POIREL Secretary of the Monitoring Committee of the Congress Cell:+ 33 6 50 39 29 10 / + 33 6 63 55 07 10 E-mail: [email protected] Consecutive interpretation: Spanish and English 1 ILDG: Independent Liberal and Democratic Group of the Congress SOC: Socialist Group of the Congress 2 Monday, 14 January 2013 Meeting with Mr Antonio Germán BETETA BARREDA, Secretary of State for Public Administration Meeting with the Members of the Spanish National Delegation to the Congress - Ms Ana Isabel ALOS LOPEZ, Mayor of Huesca, Head of the Spanish delegation to the Congress - Mr Josep Felix BALLESTEROS CASANOVA, Mayor of Tarragona - Mr Manuel CARDENAS MORENO, Mayor of Trebujena - Mr Inigo DE LA SERNA HERNAIZ, Mayor of Santander - Mrs Irene GARCIA MACIAS, Mayor of Sanlucar de Barrameda - Mr Manuel REYES LOPEZ, Mayor of Castelldefels - Mr Juan AVILA FRANCES, Mayor of Cuenca - Mrs Carmen BAYOD -

In the Elections to the Parliament of the País Vasco 1,794,313 Voters May Vote and in the Elections to the Parliament of Galicia, 2,697,315

22 de mayo de 2020 Parliamentary Elections in País Vasco and Galicia, July 12, 2020 In the elections to the Parliament of the País Vasco 1,794,313 voters may vote and in the elections to the Parliament of Galicia, 2,697,315 The electoral census can be consulted from 25 May to 1 June Voters residing abroad who wish to vote should request it by 13 June On July 12, 2020, 1,794,313 voters will be able to vote in the País Vasco parliamentary elections, and 2,697,315 in the Galicia parliamentary elections. Total voters in the País Voters residing in Voters residing abroad with municipality of Vasco parliamentary País Vasco registration in País Vasco election 1,794,313 1,718,323 75,990 Number of voters in the País Vasco parliamentary election by provinces Province Total Voters resident in: País Vasco abroad TOTAL 1,793,313 1,718,323 75,990 Araba/Álava 258,845 251,586 7,259 Bizkaia 950,563 910,071 40,492 Gipuzkoa 584,905 556,666 28,239 Total voters in the Galicia Voters residing in Voters residing abroad with municipality of parliamentary election Spain registration in Galicia 2,697,315 2,234,152 463,163 Number of voters in the Galicia parliamentary election by provinces Province Total Voters resident in: Galicia abroad TOTAL 2,695,315 2,234,152 463,163 Coruña, A 1,088,032 927,938 160,094 Lugo 342,969 275,364 67,605 Ourense 359,226 257,826 101,400 Pontevedra 907,088 773,024 134,064 Parliamentary elections, País Vasco and Galicia July 12,2020 (1/4) Of the voters living País Vasco, 68,790 will be able to participate in these elections for the first time, due to having turned 18 since the previous election for the País Vasco Parliament, held on September 25, 2016. -

ESS8 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS8 - 2016 ed. 2.1 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Czechia 7 Estonia 9 Finland 11 France 13 Germany 15 Hungary 16 Iceland 18 Ireland 20 Israel 22 Italy 24 Lithuania 26 Netherlands 29 Norway 30 Poland 32 Portugal 34 Russian Federation 37 Slovenia 40 Spain 41 Sweden 44 Switzerland 45 United Kingdom 48 Version Notes, ESS8 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS8 edition 2.1 (published 01.12.18): Czechia: Country name changed from Czech Republic to Czechia in accordance with change in ISO 3166 standard. ESS8 edition 2.0 (published 30.05.18): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Hungary, Italy, Lithuania, Portugal, Spain. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2013 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ), Social Democratic Party of Austria, 26,8% names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP), Austrian People's Party, 24.0% election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ), Freedom Party of Austria, 20,5% 4. Die Grünen - Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne), The Greens - The Green Alternative, 12,4% 5. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ), Communist Party of Austria, 1,0% 6. NEOS - Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum, NEOS - The New Austria and Liberal Forum, 5,0% 7. Piratenpartei Österreich, Pirate Party of Austria, 0,8% 8. Team Stronach für Österreich, Team Stronach for Austria, 5,7% 9. Bündnis Zukunft Österreich (BZÖ), Alliance for the Future of Austria, 3,5% Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

Revista Electrónica Teoría De La Educación. Educación Y Cultura En La Sociedad De La Información

Revista Electrónica Teoría de la Educación. Educación y Cultura en La Sociedad de la Información. Vol. 10. Nº2. Julio 2009 MONOGRÁFICO “La Alfabetización Tecnológica y el desarrollo regional”. Isabel Ortega Sánchez Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia (España) Carlos Ferrás Sexto Universidad de Santiago de Comportela (España) (Coordinadores) http://www.usal.es/teoriaeducacion ISSN 1138-9737 Revista Electrónica Teoría de la Educación. Educación y Cultura en la Sociedad de la Información. http://www.usal.es/teoriaeducacion Vol. 10. Nº 2. Julio 2009 SUMARIO “LA ALFABETIZACIÓN TECNOLÓGICA Y EL DESARROLLO REGIONAL”. EDITORIAL Editorial de Isabel Ortega Sánchez. Isabel Ortega Sánchez (Universidad Naciona de Educación a Distancia – UNED - Espa- ña). …………………………………………………………………………………..5-7 EDITORIAL: “CONSTRUYENDO LA SOCIEDAD DIGITAL. UN DESAFÍO PARA LAS CIENCIAS SOCIALES” Carlos Ferrás Sexto (Universidad de Santiago de Compostela, España) …………..8-10 MONOGRÁFICO LA ALFABETIZACIÓN TECNOLÓGICA. Isabel Ortega Sánchez (Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia – UNED – Es- paña)………………………………………………………………………………..11-24 ALFABETIZACIÓN VIRTUAL Y GESTIÓN DEL CONOCIMIENTO. Emilio López-Barajas Zayas (Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia)…25-47 BUENAS PRÁCTICAS TIC. LA ALFABETIZACIÓN DIGITAL EN MAYORES Félix Huelves Martín (ICT Education adviser, España)………………………..…48-65 COMUNIDADES VIRTUALES PRÁCTICAS DE ALFABETIZACIÓN MULTI- PLE. María García Pérez (Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia – UNED – Espa- ña) y Daniela Melaré (UNOPAR, Brasil)………………………………………....66-85 2 Revista Electrónica Teoría de la Educación. Educación y Cultura en la Sociedad de la Información. http://www.usal.es/teoriaeducacion Vol. 10. Nº 2. Julio 2009 LA INFLUENCIA DEL CONTEXTO EN LOS USOS DE LAS HERRAMIENTAS VIRTUALES. Mª Luisa Sevillano y Mª Pilar Quicios (Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia - UNED - , España)………………………………………………………………86-107 DIMENSIÓN FORMATIVA DE LA ALFABETIZACIÓN TECNOLÓGICA.