“O EUCHARI” REMIXED Lisa Colton Abbess Hildegard Von Bingen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introitus: the Entrance Chant of the Mass in the Roman Rite

Introitus: The Entrance Chant of the mass in the Roman Rite The Introit (introitus in Latin) is the proper chant which begins the Roman rite Mass. There is a unique introit with its own proper text for each Sunday and feast day of the Roman liturgy. The introit is essentially an antiphon or refrain sung by a choir, with psalm verses sung by one or more cantors or by the entire choir. Like all Gregorian chant, the introit is in Latin, sung in unison, and with texts from the Bible, predominantly from the Psalter. The introits are found in the chant book with all the Mass propers, the Graduale Romanum, which was published in 1974 for the liturgy as reformed by the Second Vatican Council. (Nearly all the introit chants are in the same place as before the reform.) Some other chant genres (e.g. the gradual) are formulaic, but the introits are not. Rather, each introit antiphon is a very unique composition with its own character. Tradition has claimed that Pope St. Gregory the Great (d.604) ordered and arranged all the chant propers, and Gregorian chant takes its very name from the great pope. But it seems likely that the proper antiphons including the introit were selected and set a bit later in the seventh century under one of Gregory’s successors. They were sung for papal liturgies by the pope’s choir, which consisted of deacons and choirboys. The melodies then spread from Rome northward throughout Europe by musical missionaries who knew all the melodies for the entire church year by heart. -

Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal Danielle Van Oort [email protected]

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 2016 Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal Danielle Van Oort [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Van Oort, Danielle, "Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal" (2016). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. Paper 1016. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. REST, SWEET NYMPHS: PASTORAL ORIGINS OF THE ENGLISH MADRIGAL A thesis submitted to the Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music Music History and Literature by Danielle Van Oort Approved by Dr. Vicki Stroeher, Committee Chairperson Dr. Ann Bingham Dr. Terry Dean, Indiana State University Marshall University May 2016 APPROVAL OF THESIS We, the faculty supervising the work of Danielle Van Oort, affirm that the thesis, Rest Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal, meets the high academic standards for original scholarship and creative work established by the School of Music and Theatre and the College of Arts and Media. This work also conforms to the editorial standards of our discipline and the Graduate College of Marshall University. With our signatures, we approve the manuscript for publication. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to express appreciation and gratitude to the faculty and staff of Marshall University’s School of Music and Theatre for their continued support. -

SALVAGUARDA DO PATRIMÔNIO CULTURAL IMATERIAL Uma Análise Comparativa Entre Brasil E Itália UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DA BAHIA

SALVAGUARDA DO PATRIMÔNIO CULTURAL IMATERIAL uma análise comparativa entre Brasil e Itália UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DA BAHIA REITOR João Carlos Salles Pires da Silva VICE-REITOR Paulo Cesar Miguez de Oliveira ASSESSOR DO REITOR Paulo Costa Lima EDITORA DA UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DA BAHIA DIRETORA Flávia Goulart Mota Garcia Rosa CONSELHO EDITORIAL Alberto Brum Novaes Angelo Szaniecki Perret Serpa Caiuby Alves da Costa Charbel Niño El Hani Cleise Furtado Mendes Evelina de Carvalho Sá Hoisel Maria do Carmo Soares de Freitas Maria Vidal de Negreiros Camargo O presente trabalho foi realizado com o apoio da Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de pessoal de nível superior – Brasil (CAPES) – Código de financiamento 001 F. Humberto Cunha Filho Tullio Scovazzi organizadores SALVAGUARDA DO PATRIMÔNIO CULTURAL IMATERIAL uma análise comparativa entre Brasil e Itália também com textos de Anita Mattes, Benedetta Ubertazzi, Mário Pragmácio, Pier Luigi Petrillo, Rodrigo Vieira Costa Salvador EDUFBA 2020 Autores, 2020. Direitos para esta edição cedidos à Edufba. Feito o Depósito Legal. Grafia atualizada conforme o Acordo Ortográfico da Língua Portuguesa de 1990, em vigor no Brasil desde 2009. capa e projeto gráfico Igor Almeida revisão Cristovão Mascarenhas normalização Bianca Rodrigues de Oliveira Sistema de Bibliotecas – SIBI/UFBA Salvaguarda do patrimônio cultural imaterial : uma análise comparativa entre Brasil e Itália / F. Humberto Cunha Filho, Tullio Scovazzi (organizadores). – Salvador : EDUFBA, 2020. 335 p. Capítulos em Português, Italiano e Inglês. ISBN: -

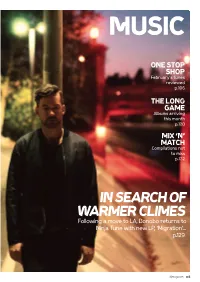

IN SEARCH of WARMER CLIMES Following a Move to LA, Bonobo Returns to Ninja Tune with New LP, ‘Migration’

MUSIC ONE STOP SHOP February’s tunes reviewed p.106 THE LONG GAME Albums arriving this month p.128 MIX ‘N’ MATCH Compilations not to miss p.132 IN SEARCH OF WARMER CLIMES Following a move to LA, Bonobo returns to Ninja Tune with new LP, ‘Migration’... p.129 djmag.com 105 HOUSE BEN ARNOLD QUICKIES Roberto Clementi Avesys EP [email protected] Pets Recordings 8.0 Sheer class from Roberto Clementi on Pets. The title track is brooding and brilliant, thick with drama, while 'Landing A Man'’s relentless thump betrays a soft and gentle side. Lovely. Jagwar Ma Give Me A Reason (Michael Mayer Does The Amoeba Remix) Marathon MONEY 8.0 SHOT! Showing that he remains the master (and managing Baba Stiltz to do so in under seven minutes too), Michael Mayer Is Everything smashes this remix of baggy dance-pop dudes Studio Barnhus Jagwar Ma out of the park. 9.5 The unnecessarily young Baba Satori Stiltz (he's 22) is producing Imani's Dress intricate, brilliantly odd house Crosstown Rebels music that bearded weirdos 8.0 twice his age would give their all chopped hardcore loops, and a brilliance from Tact Recordings Crosstown is throwing weight behind the rather mid-life crises for. Think the bouncing bassline. Sublime work. comes courtesy of roadman (the unique sound of Satori this year — there's an album dizzying brilliance of Robag small 'r' is intentional), aka coming — but ignore the understatedly epic Ewan Whrume for a reference point, Dorsia Richard Fletcher. He's also Tact's Pearson mixes of 'Imani's Dress' at your peril. -

PÉROTIN and the ARS ANTIQUA the Hilliard Ensemble

CORO hilliard live CORO hilliard live 1 The Hilliard Ensemble For more than three decades now The Hilliard Ensemble has been active in the realms of both early and contemporary music. As well as recording and performing music by composers such as Pérotin, Dufay, Josquin and Bach the ensemble has been involved in the creation of a large number of new works. James PÉROTIN MacMillan, Heinz Holliger, Arvo Pärt, Steven Hartke and many other composers have written both large and the and small-scale pieces for them. The ensemble’s performances ARS frequently include collaborations with other musicians such as the saxophonist Jan Garbarek, violinist ANTIQUA Christoph Poppen, violist Kim Kashkashian and orchestras including the New York Philharmonic, the BBC Symphony Orchestra and the Philadelphia Orchestra. John Potter’s contribution was crucial to getting the Hilliard Live project under way. John has since left to take up a post in the Music Department of York University. His place in the group has been filled by Steven Harrold. www.hilliardensemble.demon.co.uk the hilliard ensemble To find out more about CORO and to buy CDs, visit www.thesixteen.com cor16046 The hilliard live series of recordings came about for various reasons. 1 Vetus abit littera Anon. (C13th) 3:47 At the time self-published recordings were a fairly new and increasingly David James Rogers Covey-Crump John Potter Gordon Jones common phenomenon in popular music and we were keen to see if 2 Deus misertus hominis Anon. (C13th) 5:00 we could make the process work for us in the context of a series of David James Rogers Covey-Crump John Potter Gordon Jones public concerts. -

Club Cultures Music, Media and Subcultural Capital SARAH THORNTON Polity

Club Cultures Music, Media and Subcultural Capital SARAH THORNTON Polity 2 Copyright © Sarah Thornton 1995 The right of Sarah Thornton to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published in 1995 by Polity Press in association with Blackwell Publishers Ltd. Reprinted 1996, 1997, 2001 Transferred to digital print 2003 Editorial office: Polity Press 65 Bridge Street Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK Marketing and production: Blackwell Publishers Ltd 108 Cowley Road Oxford OX4 1JF, UK All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any 3 form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. ISBN: 978-0-7456-6880-2 (Multi-user ebook) A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Typeset in 10.5 on 12.5 pt Palatino by Best-set Typesetter Ltd, Hong Kong Printed and bound in Great Britain by Marston Lindsay Ross International -

Jennifer Bain1 Dalhousie University 1. Three Years Ago After I Delivered

Echo: A Music-Centered Journal Volume 6 Issue 1 (Spring 2004) Full article with images, video and audio content available at http://www.echo.ucla.edu/volume6-issue1/bain/bain1.html Jennifer Bain1 Dalhousie University 1. Three years ago after I delivered a lecture to my medieval music history class on the role of women in medieval music, one student asked the question that has been occupying me for some time: “Why is it that before I took this course I had heard of Hildegard von Bingen, but I’d never heard of any of the other medieval composers we’ve talked about so far, like Leonin or Perotin?” The answer, of course, is not straightforward. Twenty- five years ago this question would not have been asked in a medieval music history class, because very few people at all in the English-speaking world, even those who specialized in medieval music, knew the name of the twelfth-century Abbess and composer, Hildegard von Bingen (1098-1179). Before 1989, Hildegard’s music, like that of most women composers, was completely absent from standard music history textbooks.2 While she merited only a single paragraph in a 1989 textbook devoted entirely to medieval music, today she is a featured composer in the latest edition of the widely-used music history textbook, Grout and Palisca’s A History of Western Music (49, 50). This speedy rise to prominence in the study of music history, however, pales in comparison to Hildegard’s spectacular and influential splash in the marketplace. 2. Before 1982 only a few of Hildegard’s seventy-seven songs had been recorded and their amateur performances had virtually no impact in the marketplace. -

Enigma Return to Innocence Mp3, Flac, Wma

Enigma Return To Innocence mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic Album: Return To Innocence Country: Europe Released: 1993 Style: Downtempo, Ambient MP3 version RAR size: 1882 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1644 mb WMA version RAR size: 1411 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 629 Other Formats: WAV AHX AAC MOD DTS MP3 XM Tracklist Hide Credits 1 Return To Innocence (Radio Edit) 4:03 Return To Innocence (Long & Alive Version) 2 7:07 Remix – Curly M.C., Jens Gad Return To Innocence (380 Midnight Mix) 3 5:55 Remix – Jens Gad 4 Return To Innocence (Short Radio Edit) 3:01 Sadeness Part I (Radio Edit) 5 Lyrics By – Curly M.C., David FairsteinMusic By – Curly M.C., F. GregorianProducer – 4:17 Enigma Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Virgin Schallplatten GmbH Copyright (c) – Virgin Schallplatten GmbH Pressed By – EMI Jax Credits Producer, Engineer – "Curly" Michael Cretu* (tracks: 1 to 4) Vocals [Additional] – Angel* (tracks: 1 to 4) Written-By – Curly M.C. (tracks: 1 to 4) Notes Issued in a standard jewel case with front and rear inserts, black disc tray. Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode (String): 724383842322 Barcode (Text): 7 2438 38423 2 2 Matrix / Runout: 38423-2 MO RE1 S4120F Y 1-1-1 EMI JAX Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year 7243 8 92197 2 Virgin, 7243 8 92197 2 Return To Innocence 2, 8 92197 2, Enigma Virgin, 2, 8 92197 2, Europe 1993 (CD, Maxi) DINSD 123 Virgin DINSD 123 Enigma = エニグマ* - VJCP-12015, Enigma Return To Innocence Virgin, VJCP-12015, Japan 1994 DINSD 123 = エニグマ* = リターン・トゥ・イノセンス Virgin DINSD 123 (CD, EP) 7243 8 92197 6 Virgin, 7243 8 92197 6 Return To Innocence UK & 0, DINST 123, 8 Enigma Virgin, 0, DINST 123, 8 1993 (12", Maxi) Europe 92197 6 Virgin 92197 6 7243 8 92197 2 Virgin, 7243 8 92197 2 Return To Innocence 2, 8 92197 2, Enigma Virgin, 2, 8 92197 2, Europe 1993 (CD, Maxi) DINSD 123 Virgin DINSD 123 Return To Innocence 4KM-38423 Enigma Charisma 4KM-38423 US 1993 (Cass, Single) Related Music albums to Return To Innocence by Enigma Enigma - MCMXC a.D. -

The Amis Harvest Festival in Contemporary Taiwan A

?::;'CJ7 I UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII LIBRARY. THE AMIS HARVEST FESTIVAL IN CONTEMPORARY TAIWAN A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'IIN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN MUSIC MAY 2003 BY Linda Chiang Ling-chuan Kim Thesis Committee: Frederick Lau, Chairperson Ricardo Trimillos Robert Cheng ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would never have been able to finish this thesis without help from many people and organizations. I would like to first thank my husband Dennis, and my children, Darrell, Lory, Lorinda, Mei-ling, Tzu-yu, and Darren, for their patience, understanding, and encouragement which allowed me to spend two entire summers away from home studying the culture and music of the Amis people of Taiwan. I especially want to thank Dennis, for his full support of my project. He was my driver and technical assistant during the summer of 1996 as I visited many Amis villages. He helped me tape and record interviews, songs, and dances, and he spent many hours at the computer, typing my thesis, transcribing my notes, and editing for me. I had help from friends, teachers, classmates, village chiefs and village elders, and relatives in my endeavors. In Taiwan, my uncles and aunts, T'ong T'ien Kui, Pan Shou Feng, Chung Fan Ling, Hsu Sheng Ming, Chien Su Hsiang, Lo Ch'iu Ling, Li Chung Nan, and Huang Mei Hsia, all helped with their encouragement and advice. They also provided me with rides, contacts, and information. Special thanks goes to T'ong T'ien Kui and Chung Fan Ling who drove me up and down mountains, across rivers and streams, and accompanied me to many of the villages I wanted to visit. -

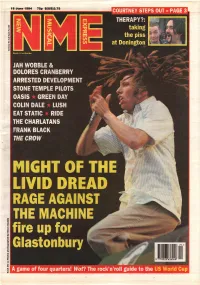

1994.06.18-NME.Pdf

INDIE 45s US 45s PICTURE: PENNIE SMITH PENNIE PICTURE: 1 I SWEAR........................ ................. AII-4-One (Blitzz) 2 I’LL REMEMBER............................. Madonna (Maverick) 3 ANYTIME, ANYPLACE...................... Janet Jackson (Virgin) 4 REGULATE....................... Warren G & Nate Dogg (Outburst) 5 THE SIGN.......... Ace Of Base (Arista) 6 DON’TTURN AROUND......................... Ace Of Base (Arista) 7 BABY I LOVE YOUR WAY....................... Big Mountain (RCA) 8 THE MOST BEAUTIFUL GIRL IN THE WORLD......... Prince(NPG) 9 YOUMEANTHEWORLDTOME.............. Toni Braxton (UFace) NETWORK UK TOP SO 4Ss 10 BACK AND FORTH......................... Aaliyah (Jive) 11 RETURN TO INNOCENCE.......................... Enigma (Virgin) 1 1 LOVE IS ALL AROUND......... ...Wet Wet Wet (Precious) 37 (—) JAILBIRD............................. Primal Scream (Creation) 12 IFYOUGO ............... ....................... JonSecada(SBK) 38 38 PATIENCE OF ANGELS. Eddi Reader (Blanco Y Negro) 13 YOUR BODY’S CALLING. R Kelly (Jive) 2 5 BABYI LOVE YOUR WAY. Big Mountain (RCA) 14 I’M READY. Tevin Campbell (Qwest) 3 11 YOU DON’T LOVE ME (NO, NO, NO).... Dawn Penn (Atlantic) 39 23 JUST A STEP FROM HEAVEN .. Eternal (EMI) 15 BUMP’N’ GRIND......................................R Kelly (Jive) 4 4 GET-A-WAY. Maxx(Pulse8) 40 31 MMMMMMMMMMMM....... Crash Test Dummies (RCA) 5 7 NO GOOD (STARTTHE DANCE)........... The Prodigy (XL) 41 37 DIE LAUGHING........ ................. Therapy? (A&M) 6 6 ABSOLUTELY FABULOUS.. Absolutely Fabulous (Spaghetti) 42 26 TAKE IT BACK ............................ Pink Floyd (EMI) 7 ( - ) ANYTIME YOU NEED A FRIEND... Mariah Carey (Columbia) 43 ( - ) HARMONICAMAN....................... Bravado (Peach) USLPs 8 3 AROUNDTHEWORLD............... East 17 (London) 44 ( - ) EASETHEPRESSURE................... 2woThird3(Epic) 9 2 COME ON YOU REDS 45 30 THEREAL THING.............. Tony Di Bart (Cleveland City) 3 THESIGN.,. Ace Of Base (Arista) 46 33 THE MOST BEAUTIFUL GIRL IN THE WORLD. -

Great Sacred Music Easter Day, April 4, 2021

Great Sacred Music Easter Day, April 4, 2021 Traditional, arr. John Rutter: Jesus Christ is risen today The Choir of Saint Thomas Church, New York City; Saint Thomas Brass, John Scott Jeremy Bruns, organ Randall Thompson: Alleluia Harvard University Choir, Murray Forbes Somerville Joseph Noyon, arr. Gerre Hancock: Christus Vincit The Choir of Saint Thomas Church, New York City; St. Thomas Brass, John Scott Jeremy Bruns, organ From Oxford University Press: Christ the Lord Is Risen Today is an arrangement of the Easter hymn tune ‘Lyra Davidica’ for SATB, optional congregation, and organ or brass choir. Dr. Murray Forbes Somerville was Gund University Organist and Choirmaster from 1990 to 2003, The Memorial Church at Harvard University. This festive Easter anthem by French composer Joseph Noyon (1888-1962) is the only piece in his extensive oeuvre which survives in common usage. Henry Ley: The strife is o'er Choir of Liverpool Cathedral, David Poulter Ian Tracey, organ Pietro Mascagni: Regina coeli (Easter Hymn) from Cavalleria rusticana Atlanta Symphony Orchestra & Choruses, Robert Shaw Christine Brewer, soprano Diane Bish: Improvisation on the hymn tune "Duke Street" Diane Bish, organ 1969 Walcker organ of the Ulm Cathedral, Austria Francis Pott translated the 17th century Latin text for "The strife is o’er” in 1861. The musical forces which appear in this morning’s performance of Mascagni’s Easter Hymn are as rich and lush as the music itself. Kansas native Diane Bish (1941-) has had a dazzling career as a professional organist. Ms. Bish has played recitals on organs worldwide. Easter Greeing: The Reverend Canon Jean Parker Vail Sir Arthur Sullivan, arr. -

Sacred & Secular Vocal

SACRED & SECULAR VOCAL SACRED WORKS BACH 333 BACH 1 2 BACH 333 SACRED WORKS SACRED AND SECULAR VOCAL Tracklists Chorales 2 Magnificat, Motets, Masses, Passions, Oratorios 16 Secular Cantatas 68 Vocal Traditions 92 Sung texts Chorales 160 Magnificat, Motets, Masses 205 St John Passion 214 St Matthew Passion 234 Easter Oratorio 263 Ascension Oratorio 265 Christmas Oratorio 268 Secular Cantatas 283 CD 49 68:51 4-Part Chorales Sung texts pp. 160–174 1 Was Gott tut, das ist wohlgetan BWV 250 0:53 2 Sei Lob und Ehr dem höchsten Gut BWV 251 0:53 3 Nun danket alle Gott BWV 252 0:52 Kölner Akademie | Michael Alexander Willens conductor 4 Ach bleib bei uns, Herr Jesu Christ BWV 253 0:38 5 Ach Gott, erhör mein Seufzen und Wehklagen BWV 254 0:48 6 Ach Gott und Herr BWV 255 0:36 7 Ach lieben Christen, seid getrost BWV 256 0:57 Augsburger Domsingknaben | Reinhard Kammler conductor CHORALES Claudia Waßner organ 8 Wär Gott nicht mit uns diese Zeit BWV 257 0:55 9 Wo Gott der Herr nicht bei uns hält BWV 258 0:56 Vocalconsort Berlin | Daniel Reuss conductor Ophira Zakai lute | Elina Albach organ BACH 333 BACH 4 10 Ach, was soll ich Sünder machen BWV 259 0:55 11 Allein Gott in der Höh sei Ehr BWV 260 0:56 12 Allein zu dir, Herr Jesu Christ BWV 261 1:13 13 Alle Menschen müssen sterben BWV 262 0:57 14 Alles ist an Gottes Segen BWV 263 0:42 15 Als der gütige Gott BWV 264 1:22 16 Als Jesus Christus in der Nacht BWV 265 1:42 17 Als vierzig Tag nach Ostern warn BWV 266 0:48 18 An Wasserflüssen Babylon BWV 267 1:23 19 Auf, auf, mein Herz, und du mein ganzer Sinn