Stravinsky's Serial "Mistakes"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

All Strings Considered a Subjective List of Classical Works

All Strings Considered A Subjective List of Classical Works & Recordings All Recordings are available from the Lake Oswego Public Library These are my faves, your mileage may vary. Bill Baars, Director Composer / Title Performer(s) Comments Middle Ages and Renaissance Sequentia We carry a lot of plainsong and chant; HILDEGARD OF BINGEN recordings by the Anonymous 4 are also Antiphons highly recommended. Various, Renaissance vocal and King’s Consort, Folger Consort instrumental collections. or Baltimore Consort Baroque Era Biondi/Europa Galante or Vivaldi wrote several hundred concerti; try VIVALDI Loveday/Marriner. the concerti for multiple instruments, and The Four Seasons the Mandolin concerti. Also, Corelli's op. 6 and Tartini (my fave is his op.96). HANDEL Asch/Scholars Baroque For more Baroque vocal, Bach’s cantatas - Messiah Ensemble, Shaw/Atlanta start with 80 & 140, and his Bach B Minor Symphony Orch. or Mass with John Gardiner conducting. And for Jacobs/Freiberg Baroque fun, Bach's “Coffee” cantata. orch. HANDEL Lamon/Tafelmusik For an encore, Handel's “Music for the Royal Water Music Suites Fireworks.” J.S. BACH Akademie für Alte Musik Also, the Suites for Orchestra; the Violin and Brandenburg Concertos Berlin or Koopman, Pinnock, Harpsicord Concerti are delightful, too. or Tafelmusik J.S. BACH Walter Gerwig More lute - anything by Paul O'Dette, Ronn Works for Lute McFarlane & Jakob Lindberg. Also interesting, the Lute-Harpsichord. J.S. BACH Bylsma on period cellos, Cello Suites Fournier on a modern instrument; Casals' recording was the standard Classical Era DuPre/Barenboim/ECO & HAYDN Barbirolli/LSO Cello Concerti HAYDN Fischer, Davis or Kuijiken "London" Symphonies (93-101) HAYDN Mosaiques or Kodaly quartets Or start with opus 9, and take it from there. -

Igor Strav Thursday 21 & Sunday 24 September

Thursday 21 & Sunday 24 September Igor Stravinsky in Profile 1882–1971 / profile by Paul Griffiths LSO SEASON CONCERT hird in a family of four sons, Before that was completed, a ballet based In 1939, soon after the deaths of his wife STRAVINSKY INTRODUCTION from Paul Griffiths he had a comfortable upbringing in on 18th-century music, Pulcinella (1919–20), and mother, he sailed to New York with St Petersburg, where his father opened the door to a whole neoclassical period, Vera, whom he married, and with whom he Stravinsky The Firebird (original ballet) Writing back to a Russian friend in 1912, was a Principal Bass at the Mariinsky Theatre. which was to last three decades and more. settled in Los Angeles. Following his opera Interval – 20 minutes as he worked in Switzerland on The Rite In 1902 he started lessons with Rimsky- He also began spending much of his time The Rake’s Progress (1947–51) he began to Stravinsky Petrushka (1947 version) of Spring, Stravinsky remarked: ‘It is as Korsakov, but he was a slow developer, in Paris and on tour with his mistress Vera interest himself in Schoenberg and Webern, Interval – 20 minutes if twenty and not two years had passed and hardly a safe bet when Diaghilev Sudeikina, while his wife, mother and children and within three years had worked out a Stravinsky The Rite of Spring since The Firebird was composed’. commissioned The Firebird. The success lived elsewhere in France. Up to the end of new serial style. Sacred works became more STRA This evening we have the rare opportunity of that work encouraged him to remain the 1920s, his big works were nearly all for and more important, to end with Requiem Sir Simon Rattle conductor to relive those packed and extraordinary in western Europe, writing scores almost the theatre (including the nine he wrote for Canticles (1965–66), which was performed two years in two hours, following the annually for Diaghilev. -

DANSES CQNCERTANTES by IGOR STRAVINSKY: an ARRANGEMENT for TWO PIANOS, FOUR HANDS by KEVIN PURRONE, B.M., M.M

DANSES CQNCERTANTES BY IGOR STRAVINSKY: AN ARRANGEMENT FOR TWO PIANOS, FOUR HANDS by KEVIN PURRONE, B.M., M.M. A DISSERTATION IN FINE ARTS Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved Accepted August, 1994 t ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to extend my appreciation to Dr. William Westney, not only for the excellent advice he offered during the course of this project, but also for the fine example he set as an artist, scholar and teacher during my years at Texas Tech University. The others on my dissertation committee-Dr. Wayne Hobbs, director of the School of Music, Dr. Kenneth Davis, Dr. Richard Weaver and Dr. Daniel Nathan-were all very helpful in inspiring me to complete this work. Ms. Barbi Dickensheet at the graduate school gave me much positive assistance in the final preparation and layout of the text. My father, Mr. Savino Purrone, as well as my family, were always very supportive. European American Music granted me permission to reprint my arrangement—this was essential, and I am thankful for their help and especially for Ms. Caroline Kane's assistance in this matter. Many other individuals assisted me, sometimes without knowing it. To all I express my heartfelt thanks and appreciation. 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ii CHAPTER L INTRODUCTION 1 n. GENERAL PRINCIPLES 3 Doubled Notes 3 Articulations 4 Melodic Material 4 Equal Roles 4 Free Redistribution of Parts 5 Practical Considerations 5 Homogeneity of Rhythm 5 Dynamics 6 Tutti GesUires 6 Homogeneity of Texmre 6 Forte-Piano Chords 7 Movement EI: Variation I 7 Conclusion 8 BIBLIOGRAPHY 9 m APPENDIX A. -

View List (.Pdf)

Symphony Society of New York Stadium Concert United States Premieres New York Philharmonic Commission as of November 30, 2020 NY PHIL Biennial Members of / musicians from the New York Philharmonic Click to jump to decade 1842-49 | 1850-59 | 1860-69 | 1870-79 | 1880-89 | 1890-99 | 1900-09 | 1910-19 | 1920-29 | 1930-39 1940-49 | 1950-59 | 1960-69 | 1970-79 | 1980-89 | 1990-99 | 2000-09 | 2010-19 | 2020 Composer Work Date Conductor 1842 – 1849 Beethoven Symphony No. 3, Sinfonia Eroica 18-Feb 1843 Hill Beethoven Symphony No. 7 18-Nov 1843 Hill Vieuxtemps Fantasia pour le Violon sur la quatrième corde 18-May 1844 Alpers Lindpaintner War Jubilee Overture 16-Nov 1844 Loder Mendelssohn The Hebrides Overture (Fingal's Cave) 16-Nov 1844 Loder Beethoven Symphony No. 8 16-Nov 1844 Loder Bennett Die Najaden (The Naiades) 1-Mar 1845 Wiegers Mendelssohn Symphony No. 3, Scottish 22-Nov 1845 Loder Mendelssohn Piano Concerto No. 1 17-Jan 1846 Hill Kalliwoda Symphony No. 1 7-Mar 1846 Boucher Furstenau Flute Concerto No. 5 7-Mar 1846 Boucher Donizetti "Tutto or Morte" from Faliero 20-May 1846 Hill Beethoven Symphony No. 9, Choral 20-May 1846 Loder Gade Grand Symphony 2-Dec 1848 Loder Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor 24-Nov 1849 Eisfeld Beethoven Symphony No. 4 24-Nov 1849 Eisfeld 1850 – 1859 Schubert Symphony in C major, Great 11-Jan 1851 Eisfeld R. Schumann Introduction and Allegro appassionato for Piano and 25-Apr 1857 Eisfeld Orchestra Litolff Chant des belges 25-Apr 1857 Eisfeld R. Schumann Overture to the Incidental Music to Byron's Dramatic 21-Nov 1857 Eisfeld Poem, Manfred 1860 - 1869 Brahms Serenade No. -

STRAVINSKY's NEO-CLASSICISM and HIS WRITING for the VIOLIN in SUITE ITALIENNE and DUO CONCERTANT by ©2016 Olivia Needham Subm

STRAVINSKY’S NEO-CLASSICISM AND HIS WRITING FOR THE VIOLIN IN SUITE ITALIENNE AND DUO CONCERTANT By ©2016 Olivia Needham Submitted to the graduate degree program in School of Music and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. ________________________________________ Chairperson: Paul Laird ________________________________________ Véronique Mathieu ________________________________________ Bryan Haaheim ________________________________________ Philip Kramp ________________________________________ Jerel Hilding Date Defended: 04/15/2016 The Dissertation Committee for Olivia Needham certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: STRAVINSKY’S NEO-CLASSICISM AND HIS WRITING FOR THE VIOLIN IN SUITE ITALIENNE AND DUO CONCERTANT ________________________________________ Chairperson: Paul Laird Date Approved: 04/15/2016 ii ABSTRACT This document is about Stravinsky and his violin writing during his neoclassical period, 1920-1951. Stravinsky is one of the most important neo-classical composers of the twentieth century. The purpose of this document is to examine how Stravinsky upholds his neoclassical aesthetic in his violin writing through his two pieces, Suite italienne and Duo Concertant. In these works, Stravinsky’s use of neoclassicism is revealed in two opposite ways. In Suite Italienne, Stravinsky based the composition upon actual music from the eighteenth century. In Duo Concertant, Stravinsky followed the stylistic features of the eighteenth century without parodying actual music from that era. Important types of violin writing are described in these two works by Stravinsky, which are then compared with examples of eighteenth-century violin writing. iii Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971) was born in Oranienbaum (now Lomonosov) in Russia near St. -

Influence of Commedia Dell‟Arte on Stravinsky‟S Suite Italienne D.M.A

Influence of Commedia dell‟Arte on Stravinsky‟s Suite Italienne D.M.A. Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Doctor of Musical Arts In the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Sachiho Cynthia Murasugi, B.M., M.A., M.B.A. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2009 Document Committee: Kia-Hui Tan, Advisor Paul Robinson Mark Rudoff Copyright by Sachiho Cynthia Murasugi 2009 Abstract Suite Italienne for violin and piano (1934) by Stravinsky is a compelling and dynamic work that is heard in recitals and on recordings. It is based on Stravinsky‟s music for Pulcinella (1920), a ballet named after a 16th century Neapolitan stock character. The purpose of this document is to examine, through the discussion of the history and characteristics of Commedia dell‟Arte ways in which this theatre genre influenced Stravinsky‟s choice of music and compositional techniques when writing Pulcinella and Suite Italienne. In conclusion the document proposes ways in which the violinist can incorporate the elements of Commedia dell‟Arte that Stravinsky utilizes in order to give a convincing and stylistic performance. ii Acknowledgments I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my advisor, Dr. Kia-Hui Tan and my committee members, Dr. Paul Robinson, Prof. Mark Rudoff, and Dr. Jon Woods. I also would like to acknowledge the generous assistance of my first advisor, the late Prof. Michael Davis. iii Vita 1986………………………………………….B.M., Manhattan School of Music 1988-1989……………………………….…..Visiting International Student, Utrecht Conservatorium 1994………………………………………….M.A., CUNY, Queens College 1994-1995……………………………………NEA Rural Residency Grant 1995-1996……………………………………Section violin, Louisiana Philharmonic 1998………………………………………….M.B.A., Tulane University 1998-2008……………………………………Part-time instructor, freelance violinist 2001………………………………………….Nebraska Arts Council Touring Artists Roster 2008 to present………………………………Lecturer in Music, Salisbury University Publications “Stravinsky‟s Suite Italienne Unmasked.” Stringendo 25.4 (2009):19. -

Summergarden

For Immediate Release July 1990 Summergarden JAZZ-INFLUENCED STRAVINSKY WORKS PERFORMED AT THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART Friday and Saturday, July 20 and 21, 7:30 p.m. Sculpture Garden open from 6:00 to 10:00 p.m. Seven jazz-influenced works by the Russian composer Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971) are presented in the third week of SUMMERGARDEN at The Museum of Modern Art. Made possible by PaineWebber Group Inc., SUMMERGARDEN offers free weekend evenings in the Museum's Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Sculpture Garden. The 1990 concert series marks the fourth collaboration between the Museum and The Juilliard School. Paul Zukofsky, artistic director of SUMMERGARDEN, conducts artists of The Juilliard School performing: La Marseillaise (Claude Joseph Rouget de Lisle) (1919) Three Pieces (1918) Histoire du soldat (1918) Souvenir d'un marche Boche (1915) Valse pour les enfants (1916-17) Piano-Rag-Music (1919) Septet (1953) Four concerts in the SUMMERGARDEN series are being specially recorded at the Museum for PaineWebber's Traditions, a weekly radio program that is broadcast on Concert Music Network in over thirty major cities across the country. The first New York broadcast is scheduled for July 22 at 9:00 p.m. on WNCN-FM. more - Friday and Saturday evenings in the Sculpture Garden of The Museum of Modern Art are made possible by PaineWebber Group Inc. 11 West 53 Street, New York, N.Y 10019-5498 Tel: 212-708-9850 Cable: MODERNART Telex: 62370 MODART Telefax: 212-708-9889 2 During SUMMERGARDEN, the Summer Cafe serves light fare and beverages. The Garden is open from 6:00 to 10:00 p.m., and concerts begin at 7:30 p.m. -

Charles Wuorinen's Reliquary for Stravinsky

From Contemporary Music Review, 2001, Vol 20, Part 4, pp 9-27 ©2001 OPA (Overseas Publishers Association) N.V. —————————————————————————————————- Charles Wuorinen's Reliquary for Stravinsky Louis Karchin New York University Wuorinen's Reliquary for Igor Stravinsky is based on the Russian composer's final sketches; Wuorinen used these as the basis for a symphonic work of great depth and intensity. In the work's opening section, the younger composer fashioned a musical continuity by forging together some of the sketches and elaborating others. In certain cases, notes were added to complete the underlying tone-rows; usually fragments had to be orchestrated. This article describes some of Wuorinen's far-reaching transformations of Stravinsky's serial procedures, and his exploration of some new 12- tone operations. There is a consideration of the work's formal dimensions, and its subtle use of pitch centricity. KEYWORDS: Reliquary, Igor Stravinsky, sketches, serialism, rotational technique, pitch centricity ______________________________________________ A little less than a third way through Wuorinen's Reliquary for Igor Stravinsky, there is an extraordinary series of events; the music seems to veer off into uncharted realms conjuring up startling shapes and colors, seeming to push the limits of what might be imagined. A trumpet motive - Db—A—C—F# — ushers in a sustained brass chord, a high piccolo trill pierces through xylophone and flute attacks, timpani accentuate a brief march-like passage for basses, cellos and tuba, and a tam-tam begins to amplify yet a new series of bold harmonies and tantalizing contours. How was such a passage inspired and how was it composed? It occurs between measures 132 and 142 of the Reliquary; it may likewise be found about midway through program number 22 on the magnificent recording of this work by Oliver Knussen and the London Sinfonietta (Deutsche Grammophon 447-068-2). -

CHAN 9408 Cover.Qxd 26/3/08 11:34 Am Page 1

CHAN 9408 cover.qxd 26/3/08 11:34 am Page 1 Chan 9408 CHANDOS Stravinsky The Rite of Spring Requiem Canticles + Canticum Sacrum Orchestre de la Suisse Romande Neeme Järvi CHAN 9408 BOOK.qxd 26/3/08 11:37 am Page 2 Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971) The Rite of Spring 32:42 PART I – Adoration of the Earth 1 Introduction – 3:13 2 The Augurs of Spring – Dances of the Young Girls – 3:46 3 Ritual of Abduction – 1:20 4 Spring Rounds – 3:31 5 Ritual of the River Tribes – 1:51 6 Procession of the Sage – 0:43 7 The Sage – 0:23 8 Dance of the Earth 1:16 PART II – The Sacrifice 9 Introduction – 3:57 10 Mystic Circles of the Young Girls – 3:11 11 Igor Stravinsky Glorification of the Chosen One – 1:26 12 0:49 AKG London Evocation of the Ancestors – 13 Ritual Action of the Ancestors – 3:06 14 Sacrificial Dance (The Chosen One) 4:09 Raynal Malsam bassoon solo 3 CHAN 9408 BOOK.qxd 26/3/08 11:37 am Page 4 Canticum Sacrum 16:40 Chorale Variations 10:40 15 Dedicatio 0:40 on the Christmas Carol ‘Vom Himmel hoch, da komm’ ich 16 III Euntes in mundum 1:59 her’ (J. S. Bach) 17 III Surge, aquilo 2:25 32 Chorale 0:48 III Ad Tres Virtutes Hortationes 0:41 33 Variation I In canone all’Ottava 1:13 18 Caritas – 2:12 34 Variation II Alio modo in canone alla Quinta 1:14 19 Spes – 1:47 35 Variation III In canone alla Settima 1:51 20 Fides 2:46 36 Variation IV In canone all’Ottava per augmentationem 2:30 21 IV Brevis Motus Cantilenae 2:41 37 Variation V L’altra sorte del canone al rovescio 3:04 22 IV Illi autem profecti 1:58 TT 74:35 Requiem Canticles 14:01 Irène Friedli alto 23 Prelude 1:06 Frieder Lang tenor 24 Exaudi 1:34 Michel Brodard bass 25 Dies irae – 0:58 Chœur Pro Arte de Lausanne 26 Tuba mirum 1:07 Chœur de Chambre Romande 27 Interlude 2:31 André Charlet choir master 28 Rex tremendae 1:17 Orchestre de la Suisse Romande 29 Lacrimosa 1:55 Jean Piguet leader 30 Libera me 0:58 31 Postlude 2:18 Neeme Järvi 4 5 CHAN 9408 BOOK.qxd 26/3/08 11:37 am Page 6 process too. -

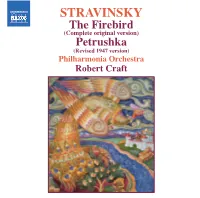

STRAVINSKY the Firebird

557500 bk Firebird US 14/01/2005 12:19pm Page 8 Philharmonia Orchestra STRAVINSKY The Philharmonia Orchestra, continuing under the renowned German maestro Christoph von Dohnanyi as Principal Conductor, has consolidated its central position in British musical life, not only in London, where it is Resident Orchestra at the Royal Festival Hall, but also through regional residencies in Bedford, Leicester and Basingstoke, The Firebird and more recently Bristol. In recent seasons the orchestra has not only won several major awards but also received (Complete original version) unanimous critical acclaim for its innovative programming policy and commitment to new music. Established in 1945 primarily for recordings, the Philharmonia Orchestra went on to attract some of this century’s greatest conductors, such as Furtwängler, Richard Strauss, Toscanini, Cantelli and von Karajan. Otto Klemperer was the Petrushka first of many outstanding Principal Conductors throughout the orchestra’s history, including Maazel, Muti, (Revised 1947 version) Sinopoli, Giulini, Davis, Ashkenazy and Salonen. As the world’s most recorded symphony orchestra with well over a thousand releases to its credit, the Philharmonia Orchestra also plays a prominent rôle as one of the United Kingdom’s most energetic musical ambassadors, touring extensively in addition to prestigious residencies in Paris, Philharmonia Orchestra Athens and New York. The Philharmonia Orchestra’s unparalleled international reputation continues to attract the cream of Europe’s talented young players to its ranks. This, combined with its brilliant roster of conductors and Robert Craft soloists, and the unique warmth of sound and vitality it brings to a vast range of repertoire, ensures performances of outstanding calibre greeted by the highest critical praise. -

A Comparison of Rhythm, Articulation, and Harmony in Jean-Michel Defaye's À La Manière De Stravinsky Pour Trombone Et Piano

A COMPARISON OF RHYTHM, ARTICULATION, AND HARMONY IN JEAN- MICHEL DEFAYE’S À LA MANIÈRE DE STRAVINSKY POUR TROMBONE ET PIANO TO COM MON COMPOSITIONAL STRATEGIES OF IGOR STRAVINSKY Dustin Kyle Mullins, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2014 APPROVED: Tony Baker, Major Professor Eugene Corporon, Minor Professor John Holt, Committee Member and Chair of the Division of Instrumental Studies James Scott, Dean of the College of Music Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Mullins, Dustin Kyle. A Comparison of Rhythm, Articulation, and Harmony in Jean-Michel Defaye’s À la Manière de Stravinsky pour Trombone et Piano to Common Compositional Strategies of Igor Stravinsky. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2014, 45 pp., 2 tables, 27 examples, references, 28 titles. À la Manière de Stravinsky is one piece in a series of works composed by Jean- Michel Defaye that written emulating the compositional styles of significant composers of the past. This dissertation compares Defaye’s work to common compositional practices of Igor Stravinsky (1882 – 1971). There is currently limited study of Defaye’s set of À la Manière pieces and their imitative characteristics. The first section of this dissertation presents the significance of the project, current literature, and methods of examination. The next section provides critical information on Jean-Michel Defaye and Igor Stravinsky. The following three chapters contain a compositional comparison of À la Manière de Stravinsky to Stravinsky’s use of rhythm, articulation, and harmony. The final section draws a conclusion of the piece’s significance in the solo trombone repertoire. -

MTO 18.4: Straus, Three Stravinsky Analyses

Volume 18, Number 4, December 2012 Copyright © 2012 Society for Music Theory Three Stravinsky Analyses: Petrushka, Scene 1 (to Rehearsal No. 8); The Rake’s Progress, Act III, Scene 3 (“In a foolish dream”); Requiem Canticles, “Exaudi” Joseph N. Straus NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.12.18.4/mto.12.18.4.straus.php KEYWORDS: Stravinsky, Petrushka, The Rake’s Progress, Requiem Canticles, analysis, melody, harmony, symmetry, collection, recomposition, prolongation, rhythm and meter, textural blocks ABSTRACT: Most published work in our field privileges theory over analysis, with analysis acting as a subordinate testing ground and exemplification for a theory. Reversing that customary polarity, this article analyzes three works by Stravinsky (Petrushka, The Rake’s Progress, Requiem Canticles) with a relative minimum of theoretical preconceptions and with the simple aim, in David Lewin’s words, of “hearing the piece[s] better.” Received February 2012 [1] In his classic description of the relationship between theory and analysis, David Lewin states that theory describes the way that musical sounds are “conceptually structured categorically prior to any one specific piece,” whereas analysis turns our attention to “the individuality of the specific piece of music under study,” with a goal “simply to hear the piece better, both in detail and in the large” (Lewin 1968, 61-63, italics in original). In practice, we create theories in order to engender and empower analysis and we use analysis as a proving ground for our theories. In the field of music theory as currently constituted, theory-based analysis and analysis-oriented theory are the principal and the statistically predominant activities.