Reconstructing the Violin Part to Fredrik Pacius's Duo for Violin And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Orchestral Works He Had Played in His 35-Year Tenure in the Orchestra

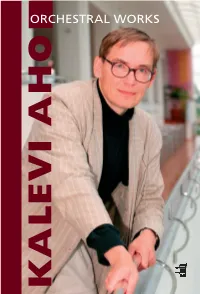

KALEVI AHO ORCHESTRAL WORKS KALEVI AHO – a composer of contrasts and surprises alevi Aho (born in Finland in 1949) possesses one of today’s most exciting creative voices. A composer with one foot in the past and one in the pres- K ent, he combines influences from the most disparate sources and transforms them through his creative and emotional filter into something quite unique. He does not believe in complexity simply for the sake of it. His music always communicates directly with the listener, being simultaneously ‘easy’ yet ‘difficult’, but never banal, over-intellectual, introvert or aloof. In his own words, “A composer should write all sorts of works, so that something will always evoke an echo in people in different life situations. Music should come to the help of people in distress or give them an ex- perience of beauty.” Kalevi Aho is equally natural and unaffected in his symphonies and operas as he is in his intimate musical miniatures. Monumental landscapes painted in broad brush- strokes go hand in hand with delicate watercolours, serious artistic confessions and humour. The spectrum of human emotions is always wide, and he never lets his lis- teners off lightly. He poses questions and sows the seeds of thoughts and impulses that continue to germinate long after the last note has died away. “His slightly unassuming yet always kind appearance is vaguely reminiscent of Shosta- kovich, while his musical voice, with its pluralistic conception of the world and its intricate balance between the deliberately banal and the subtle, is undoubtedly closer to late Mahler.” It is easy to agree with this anonymous opinion of Kalevi Aho. -

Fredrik Pacius Ja Richard Faltin – Kaks Fredrik Pacius Ja Richard Faltin – Kaks Sakslast Soome Muusikaelu Rajamas Sakslast Soome Muusikaelu Rajamas

korraldada nendega unustamatuid kontserte. Fredrik Pacius ja Richard Lihtne see siiski polnud ja meil on võimatu Faltin – kaks sakslast Soome teada saada, kuidas Paciuse omaaegsed kontserdid tegelikult kõlasid. Arvatavasti ei muusikaelu rajamas piisanud asjaarmastajate tehnilistest oskustest — nüüdisaja mõttes suurte esteetiliste naudingute Seija Lappalainen valmistamiseks. (tõlkinud Merike Vaitmaa) Fredrik Pacius puutus oma töös kokku mitmesuguste praktiliste probleemidega. Kust leida sobivaid lauljaid ja eri pillide mängijaid Soome hümni loojat, Saksamaal sündinud kontsertideks ja akadeemilisteks pidustusteks? Friedrich (Fredrik) Paciust (Hamburg 1809 – Kuidas kasvatada harrastajatest nõudlike vokaal- Helsingi 1891) on nimetatud soome muusika ja orkestriteoste esitajaid? Oleks huvitav teada, isaks. Pacius on tõepoolest seda aunime milline orkestrikoosseis oli Paciusel mingil ajal väärt, sest tema tähtsus 19. sajandi Soome kasutada. Kui instrumente jäi puudu, siis tuli muusikaelus on ainulaadne. Ülikoolilinna Turu need muidugi asendada mingite teiste pillidega muusikaelu 1640. aastatest kuni Turu suure või teos ümber orkestreerida. Pacius juhatas tulekahjuni 1827. aastal oli küll olnud väärtuslik ja nii orkestrit kui ka koore. Ta ise oli saanud rajanud vundamendi edaspidisele – meenutatagu muusikahariduse peamiselt viiuldaja ja heli- näiteks akadeemilise ringkonna varajast loojana. Orkestratsiooniõpingud olid küll pannud muusikaharrastust ja Turu pillimänguseltsi aluse eri pillide tundmisele. Et astuda asutamist 1790. aastal. 25-aastaselt -

Humanism As Symphonic Fuel

MATS LILJEROOS constitutes a stylistically independent project. The writer is a musicologist, freelance writer on music and music critic of the daily newspaper Hufvudstadsbladet. The Sixth Symphony had explored one avenue to the end and it was time to fi nd a new angle on the symphonic problem. AN ABSOLUTE SYMPHONIC Humanism as symphonic fuel AESTHETIC Kalevi Aho’s music reaches out into new territories If the ”abstract intrigue” so prominent in Aho’s mainly non-programmatic music is absent in the programmatic, post-modernist Seventh Sym- phony (virtually unique among the Aho sympho- nies), then Aho is back on home ground in the extremely demanding Piano Concerto and the Imagine a steep mountainside in seances via evocative tone paintings of the mid- OPERATIC SATIRE WITH massive Eighth Symphony (1993) for organ and the heart of myth-drenched Finnish winter darkness and the midnight sun to a raging A CRITICAL BARB orchestra. In the Piano Concerto he continues storm in the mountains, in four movements of to tackle the individual-collective relationship Lapland. In the background a majestic very varied character. The Neoclassical and at times tonal traits of the and pursues his thesis (with the soloist to guide fell, in the foreground a deep valley fi rst period were replaced by a more modernis- him on his journey) of the abstract intrigue to STRIKING IDIOM tic approach in the structurally and emotionally unprecedented heights. The same tendency is against a backdrop of dusky forests intricate Fifth Symphony (1975–76), which is al- apparent in the broadly-conceived Eighth Sym- and bare mountains. -

Germany As a Cultural Paragon Transferring Modern Musical Life from Central Europe to Finland

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto Germany as a Cultural Paragon Transferring Modern Musical Life from Central Europe to Finland By Vesa Kurkela and Saijaleena Rantanen Introduction From the customary point of view, the two decades before and after the turn of the 20th century form the era when the national music culture of Finland was born. During these years, the first symphony orchestra (1882), the first conservatory (1882), the Finnish National Opera (1911), the Finnish Musicological Society (1916) and the first chair of musicology at the University of Helsinki (1918) were founded.1 Further, in the wake of the first symphonies (1900–1902) and other orchestral music by Jean Sibelius, the concept of ‘national style’ was born, and Finnish orchestral music witnessed a breakthrough in the Western world.2 In addition, the years between the mid-1880s and the Great War became famous for national song festivals with unprecedented large audiences and a great number of performers: thousands of nationally-inspired citizens assembled at the festivals, organised almost every summer in regional centres, in order to listen to tens of choirs, brass bands, string orchestras and solo performances.3 On closer inspection, however, we also find the formation of a new music culture in the transnational context of general European music, both art and popular. This development can be seen as a long-lasting process, in which German music and musical culture were transformed and translated to a prominent part of modern national culture in Finland. -

THE GERMAN INFLUENCE on FINNISH VIOLIN MUSIC from the NINETEENTH CENTURY Sebastian Silén

THE GERMAN INFLUENCE ON FINNISH VIOLIN MUSIC FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY Sebastian Silén YouTube link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=67ATdA76qV8&list=PLLdPJXjA- sYJVoG41XXttLuk8ddxdH3Uy&index=55 Excerpts from: Fredrik Pacius: - Variationer öfver motivet “Studenter äro muntra bröder” (0.08) - Duo for Violin and Piano (14.13) Robert Kajanus: - Scherzo (22.56) - Air élégiaque (25.32) - Berceuse (35.25) This text serves as a summary of a lecture recital which was performed on September 5, 2018, in Juozas Karoasa Hall during the Doctors in Performance conference in Vilnius. The presentation was part of an artistic project whose primary goal was to record a CD containing largely neglected music for violin and piano by Fredrik Pacius (1809-1891), Robert Kajanus (1856-1933), and Jean Sibelius (1865-1957). The CD will be released by SibaRecords by the end of 2019. The recording constitutes a part of an artistic doctoral work titled Contextualizing Jean Sibelius's Works for Violin and Piano at the Sibelius Academy in Helsinki, Finland. The project has focused on these three composers for several reasons. My artistic doctoral work explores the Nordic musical context surrounding Jean Sibelius's violin works, searching for similarities and differences between Sibelius's works and works for violin and piano by his Nordic contemporaries. In order to understand the music which Sibelius composed during his early career, a natural starting point is to begin by exploring Finnish music from the nineteenth century. Pacius, Kajanus, and Sibelius were among the most influential figures in Finnish music history and played an invaluable role in developing Finland's culture. -

Estonia Above All: the Notion and Definition of Estonia in 19Th Century Lyrics

Estonia above All: The Notion and Definition of Estonia in 19th Century Lyrics Õnne Kepp In the literature of small nations created by authors whose fate, like that of the whole of the nation, has always been dependent on militant and self-interested neighbours or the ambitions of great powers, the relations between the writer, his people and country should be of special significance. Even taking a cursory glance at Estonian poetry, one notices the frequent use of the words ‘Estonia’, ‘Estonian people’, ‘the Estonian language’ and ‘an Estonian’. In different periods and under different conditions these have been understood, expressed and treated differently. e semantics of the fatherland and its usage is central in the ideology of national movements, and therefore it is of interest to observe its occurrence dur- ing the period of the national awakening and the formative years preceding it. How was the notion and definition of Estonia shaped in Estonian poetry? Being first and foremost associated with the concept of fatherland, separating ‘Estonia’ from the fatherland is quite a violent enterprise. But still, ‘Estonia’ car- ries a heavier semantic accent, while ‘fatherland’ functions rather as a romantic myth and a symbol. In addition, Ea Jansen makes a third distinction and brings in ‘home(land)’ by saying ‘fatherland is “the home of a nation”’ ( Jansen 2004: 5).1 us, ‘fatherland’ has a special emotional content for a nation. ‘Estonia’ as a con- cept is more neutral and definite. As a rule the following discussion is based on the poetic use of the word ‘Estonia’, without breaking, if need be, the association with its twin notion in the coherent (patriotic) unit. -

Helsinki on Foot 5 Walking Routes Around Town

See Helsinki on Foot 5 walking routes around town s ap m r a e l C 1 6 km 6 km 2,5 km 6 km 4 km 2 SEE HELSINKI ON FOOT 5 walking routes around town Tip! More information about the architects mentioned in the text can be found on the back cover of the brochure. Routes See Helsinki on Foot – 5 walking routes around town 6 km Published by Helsinki City Tourist & Convention Bureau / Helsinki Travel Marketing Ltd 6 km DISCOVER THE HISTORIC CITY CENTRE Design and layout by Rebekka Lehtola Senate Square–Kruununhaka–Katajanokka 5 Translation by Crockford Communications 2,5 km Printed by Art-Print Oy 2011 Printed on Multiart Silk 150 g/m2, Galerie Fine silk 90 g/m² 6 km RELAX IN THE GREEN HEART OF THE CITY Descriptions of public art by Helsinki City Art Museum Photos courtesy of Helsinki Tourism Material Bank, Central Railway Station–Eläintarha–Töölö 10 Helsinki City Material Bank: Roy Koto, Sakke Somerma, 4 km Anu-Liina Ginström, Hannu Bask, Mika Lappalainen, Matti Tirri, Esko Jämsä, Kimmo Brandt, Juhani Seppovaara, Pertti DELIGHT YOUR SENSES IN THE DESIGN DISTRICT Nisonen, Mikko Uro, Mirva Hokkanen, Arno de la Chapelle, Esplanadi–Bulevardi–Punavuori 17 Comma Image Oy; Helsinki City Museum photo archives, Mark Heithoff, Jussi Tiainen, Flickr.com Helsinki City Photo Competition: sashapo ENJOY THE SMELL OF THE SEA Maps: © City Survey Division, Helsinki § 001/2011 Market Square–Kaivopuisto–Eira 23 Special thanks to: Senior Researcher Martti Helminen, City of Helsinki Urban Facts Hannele Pakarinen, Helsinki City Real Estate Department EXPLORE THE COLOURFUL STREET CORNERS OF KALLIO Teija Mononen, Helsinki City Art Museum This brochure includes paid advertising. -

Katrina Kammarmusik 2011

KATRINA KAMMARMUSIK ÅLAND 1-6 AUGUSTI 2011 KONSTNÄRLIG LEDARE: TIILA KANGAS 1 KKulturföreningen Katrina KATRINA KAMMARMUSIK ÅLAND 1-6 AUGUSTI 2011 Kära kammarmusikvänner, Efter att ha skrivit välkomstorden till programboken ett antal gånger under ett antal år börjar jag oundvikligen undra om jag längre har något att tillägga – förutom, naturligtvis, att önska er alla lika hjärtligt välkomna som alla tidigare år. Detsamma gäller också för själva festivalprogram- met – har jag lyckats med att skapa en helhet med nytt och gammalt och göra det till en tilltalande blandning – än en gång? Det enda sättet att få ett svar på den senare frågan – för mina ord är sist och slutligen inte lika viktiga – är att gå och lyssna på konserterna och att uppleva musiken och festivalstämningen. För genomläsning av programmet ger ändå bara en idé om det som under veckan blir Katrina Kammarmusik 2011. Musiken ska- pas i nuet, och möjligheten att delta i detta nu är det finaste, enligt min åsikt, som jag som konstnärlig ledare tillsammans med den övriga organisationen kan bjuda på. Årets festivaltema är ”Brev och resor till havs”. Katrina tar också aktivt del i ett Åbo2011-kulturhuvudstadsprojekt som kallas ”Klingande brev” och som består av kon- serter längs den gamla Postvägen mellan Stockholm och Åbo. Så även på Åland. Vi börjar kammarmusikveckan i Eckerö Post- och tullhus med mellanstopp i Hammarland, Saltvik och Vårdö. Vi fortsätter via Kumlinge och Lappo mot Åbo. Flera av konsertprogrammen har också anknytningar till brevens och postens värld. Klingande brevprojektet har beställt tre nya verk av tre högintressanta nordiska tonsät- tare; Britta Byström, Sebastian Fagerlund och Ella Grüssner Cromwell-Morgan. -

Radio 3 Listings for 11 – 17 January 2020 Page

Radio 3 Listings for 11 – 17 January 2020 Page 1 of 12 SATURDAY 11 JANUARY 2020 05:13 AM Pirashanna Thevarajah (ghatam, morsing and konnakol) Leopold Kozeluch (1747-1818) BBC Singers SAT 01:00 Through the Night (m000czrb) Pastorale in G major London Philharmonic Orchestra A 'fiendishly difficult' concerto and a 'semi-barbaric' symphony Pieter van Dijk (organ) David Murphy (conductor) LPO LPO0115 (2 CDs) Brahms’ Violin Concerto and Tchaikovsky's 4th Symphony 05:18 AM https://www.lpo.org.uk/recordings-and-gifts/5557-cd-ravi- from the Barcelona Symphony and Catalonian National Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) shankar-s-sukanya.html Orchestra. Presented by Jonathan Swain. Concerto for violin and orchestra (RV.234) in D major "L'Inquietudine" 9.30am Building a Library 01:01 AM Giuliano Carmignola (violin), Sonatori de la Gioiosa Marca Antonin Dvorak (1841-1904) Lucy Parham discusses a wide range of approaches to Brahms's Carnival Overture, Op 92 05:24 AM Piano Quintet in F minor, Op 34, and recommends the key Barcelona Symphony and Catalonia National Orchestra, Daniele Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) recording to have. Rustioni (conductor) Piano Sonata in C major K.545 Young-Lan Han (piano) 10.20am – New Releases 01:11 AM Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) 05:34 AM Beethoven: König Stephan; Leonore Prohaska; Opferlied, Violin Concerto in D major, Op 77 Erik Tulindberg (1761-1814) Germania Veronika Eberle (violin), Barcelona Symphony and Catalonia String Quartet no 3 in C major Reetta Haavisto (soprano) National Orchestra, Daniele Rustioni (conductor) -

Sheet Music Catalogue 3P.Indd

sheet music catalogue Nuottiluettelo Languages of vocal works / Kielet: Abbreviations / Lyhenteet: Fi Finnish / suomi Ch Chorus series / Chorus-sarja Eng English / englanti FEEM Fazer Editions of Early Music Sw Swedish / ruotsi * Works that due to copyright reasons are Da Danish / tanska sold only in Finland / teokset, Ger German / saksa jotka myynnissä vain Suomessa Fr French / ranska POD Print on demand item / tilauspohjainen tuote It Italian / italia Lat Latin / latina Est Estonian / viro Hu Hungarian Ru Russian / venäjä Sp Spanish / espanja X wordless, vocalise or phonetics / ei sanoja, vokaliisi tai foneettiset merkit A separate hire catalogue is available at request. Vuokrattavat nuotit löytyvät erillisestä luettelosta (hire catalogue). The product numbers indicate ISMN codes. For complete ISMN codes add 979-0 before the indicated Tuotteiden numerot ovat ISMN-koodeja. Täydellinen number (e.g. 979-0-042-06529-7). If ISMN numbers koodi muodostetaan lisäämällä numeron eteen 979-0 are not given, the work is a print on demand item (esim. 979-0-042-06529-7). Jos tuotteella ei ole ISMN- (POD). koodia, on se tilauspohjainen nuotti (Print on demand, POD). Sales: www.fennicagehrman.fi (web shop) or music shops: e.g. Myynti: ostinato@ostinato.fi or [email protected] www.fennicagehrman.fi (verkkokauppa) tai musiikkikaupat, esim. ostinato@ostinato.fi tai Distribution in Finland (dealers): [email protected] Kirjavälitys Hakakalliontie 10 Jakelu Suomessa (jälleenmyyjät): FI-05460 Hyvinkää, Finland Kirjavälitys Tel. +358 10 345 1520 Hakakalliontie 10 Fax +358 10 345 1454 FI-05460 Hyvinkää, Finland E-mail: kvtilaus@kirjavalitys.fi Puh. 010-345 1520 www.kirjavalitys.fi Fax 010-345 1454 Sähköposti: kvtilaus@kirjavalitys.fi Distribution in other countries : www.kirjavalitys.fi See our web site at www.fennicagehrman.fi (how to order) for more information or contact info@ fennicagehrman.fi PO Box 158, FI-00121 Helsinki, Finland Tel. -

OPERA CLASSICS 8.225317-18 He Has Been Artistic Director of Choirs for Bulgarian Television and Taught Choral Conducting at the Plovdiv Conservatory

225317-18 bk Pacius 11/27/06 11:19 AM Page 12 Ognian Vassiliev DDD Ognian Vassiliev, chorus-master, graduated from the Sofia conservatory as a choral conductor in 1977. OPERA CLASSICS 8.225317-18 He has been artistic director of choirs for Bulgarian television and taught choral conducting at the Plovdiv conservatory. He moved to Finland in 1991 and has founded and directed several choirs in Pori, achieving success in notable choral competitions. The Pori Musical Society PACIUS The Pori Musical Society established an orchestra in Pori, on the west coast of Finland, as early as 1877. This amateur ensemble performed principally light music and dances; classical music started to appear on the programmes in 1902. The Pori City Orchestra, nowadays known as the Pori Sinfonietta, was established in 1938 when the amateur orchestra and Pori Orchestral Society joined forces. By the late 1970s all of the players (28) were professional musicians. The Pori Sinfonietta gives symphony, chamber and church concerts as well as performing The Hunt of light music and children’s concerts; it also plays at opera productions in Pori and Vaasa. The orchestra has also appeared in Sweden and Hungary, and its principal conductors have included Juhani Numminen, Hannu Koivula, Juhani Lamminmäki and Ari Rasilainen. King Charles Ari Rasilainen Ari Rasilainen, conductor (b. 1959), started his career as a violinist in the Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra and Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra. He studied conducting under Jorma Panula at the Sibelius Academy, and later under Arvid Jansons and Alexander Labko. He made Aalto • Kattelus his international breakthrough in 1989 when he won second prize in the Nicolai Malko competition in Denmark. -

Fredrik Paciuksen Muistomerkki Helsingissä – Taiteilijavalinta 1894–1895

Mari Tossavainen Fredrik Paciuksen muistomerkki Helsingissä – taiteilijavalinta 1894–1895 Säveltäjä Fredrik Paciuksen muistomerkki valmistui Helsingin Kaisaniemen puistoon kesäkuussa 1895. Muistomerkin tekijäksi oli valittu kuvanveistäjä Emil Wikström (1864–1942). Fredrik Paciusta (1809–1891) pidettiin maan musiikki- elämän perustajana, ja kuolemansa jälkeen häntä kutsuttiin ”Suomen musiikin isäksi”. Etenkin säveltämiensä Maamme-laulun (1848), Suomen kansallislaulun, sekä Suomen laulun ansiosta hänestä tuli kansallinen ikoni.1 Yhtenä suurmiehi- syyden merkkinä voidaan pitää muistomerkkiä pääkaupungissa.2 Paciuksen rinta- kuva olikin Suomen ensimmäisiä taiteilijalle omistettuja henkilömuistomerkkejä.3 Kymmenen vuotta aiemmin Helsingin Esplanadille oli valmistunut Maamme-lau- lun tekstin kirjoittaneen runoilija J. L. Runebergin muistomerkki. Fredrik Paciuksen muistomerkkiä on käsitelty kohtalaisen vähän kirjallisuudes- sa, eikä muistomerkkihanketta ole juurikaan tutkittu.4 Tähän on useita syitä, jotka liittyvät tutkimuksen käytettävissä oleviin lähteisiin, metodologiaan sekä ehkä myös kiinnostuksen puutteeseen. Paciuksen muistomerkki kuuluu Emil Wikströmin ateljeekodin Visavuoren elokuun 1896 tulipaloa edeltäneeseen aikaan. Tulipalo tuhosi Wikströmin nuoruusvuosien ja varhaisen kuvanveistäjäuran asiakirjoja ja töitä. Osittain tästä syystä Wikströmin kuvanveistäjäuran varhaisajoista, Pacius mukaan luettuna, tiedetään vähemmän kuin taiteilijan muista vaiheista. 1 Vuonna 1835 Fredrik Pacius oli Suomen ainoa koulutettu ammattisäveltäjä. Karl