The Regulation of Covert Surveillance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Head 122 — HONG KONG POLICE FORCE

Head 122 — HONG KONG POLICE FORCE Controlling officer: the Commissioner of Police will account for expenditure under this Head. Estimate 2002–03................................................................................................................................... 12,445.8m Establishment ceiling 2002–03 (notional annual mid-point salary value) representing an estimated 34 597 non-directorate posts at 31 March 2002 reducing by 337 posts to 34 260 posts at 31 March 2003......................................................................................................................................... 9,473.1m In addition there will be 77 directorate posts at 31 March 2002 and at 31 March 2003. Capital Account commitment balance................................................................................................. 305.3m Controlling Officer’s Report Programmes Programme (1) Maintenance of Law and These programmes contribute to Policy Area 9: Internal Security Order in the Community (Secretary for Security). Programme (2) Prevention and Detection of Crime Programme (3) Reduction of Traffic Accidents Programme (4) Operations Detail Programme (1): Maintenance of Law and Order in the Community 2000–01 2001–02 2001–02 2002–03 (Actual) (Approved) (Revised) (Estimate) Financial provision ($m) 6,223.6 5,995.3 5,986.4 6,081.8 (–3.7%) (–0.1%) (+1.6%) Aim 2 The aim is to maintain law and order through the deployment of efficient and well-equipped uniformed police personnel throughout the land regions. Brief Description 3 Law -

THE TAKE-OFF of DRONES Developing the New Zealand Torts

ASHLEY M VARNEY THE TAKE-OFF OF DRONES Developing the New Zealand torts of privacy to meet the rise in civilian drone technology Submitted for the LLB (Honours) Degree Faculty of Law Victoria University of Wellington 2016 Abstract This paper assesses the privacy ramifications associated with the rise in the use of civilian drone technology. It discusses the capabilities of drones to take photographs, record videos and undertake ongoing surveillance, and distinguishes these capabilities from previous similar technologies such as CCTV and standard cameras. It is argued that the current approach to the New Zealand privacy torts is not adequate to allow for effective claims when breaches of privacy occur by drone operators. It is advocated that the theoretical premise of the torts, and the overall protection of privacy, is best served by emphasis on both a normative and multifaceted approach to the test of a reasonable expectation of privacy where drones are concerned. Moreover, privacy breaches by drones may be undermined by the highly offensive requirement found within both torts, as well as the mental element of intention found within the C v Holland tort. Keywords: "Drones", "Privacy", "Tort", "Wrongful Publication of Private Facts", "Intrusion into Seclusion". 2 Contents I INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................ 4 II UNDERSTANDING PRIVACY ...................................................................... 5 A What is ‘Privacy’? ............................................................................................. -

Personal Data Protection

Factsheet – Personal data protection May 2021 This factsheet does not bind the Court and is not exhaustive Personal data protection “The mere storing of data relating to the private life of an individual amounts to an interference within the meaning of Article 8 [of the European Convention on Human Rights, which guarantees the right to respect for private and family life, home and correspondence1] ... The subsequent use of the stored information has no bearing on that finding ... However, in determining whether the personal information retained by the authorities involves any ... private-life [aspect] ..., the Court will have due regard to the specific context in which the information at issue has been recorded and retained, the nature of the records, the way in which these records are used and processed and the results that may be obtained ...” (S. and Marper v. the United Kingdom, judgment (Grand Chamber) of 4 December 2008, § 67) Collection of personal data DNA information and fingerprints See below, under “Storage and use of personal data”, “In the context of police and criminal justice”. GPS data Uzun v. Germany 2 September 2010 The applicant, suspected of involvement in bomb attacks by a left-wing extremist movement, complained in particular that his surveillance via GPS and the use of the data obtained thereby in the criminal proceedings against him had violated his right to respect for private life. The Court held that there had been no violation of Article 8 of the Convention. The GPS surveillance and the processing and use of the data thereby obtained had admittedly interfered with the applicant’s right to respect for his private life. -

Privacy in the 21St Century Studies in Intercultural Human Rights

Privacy in the 21st Century Studies in Intercultural Human Rights Editor-in-Chief Siegfried Wiessner St. Thomas University Board of Editors W. Michael Reisman, Yale University • Mahnoush H. Arsanjani, United Nations • Nora Demleitner, Hofstra University • Christof Heyns, University of Pretoria • Eckart Klein, University of Potsdam • Kalliopi Koufa, University of Thessaloniki • Makau Mutua, State University of New York at Buff alo • Martin Nettesheim, University of Tübingen; University of California at Berkeley • Thomas Oppermann, University 0f Tübingen • Roza Pati, St. Thomas University • Herbert Petzold, Former Registrar, European Court of Human Rights • Martin Scheinin, European University Institute, Florence VOLUME 5 This series off ers pathbreaking studies in the dynamic fi eld of intercultural hu- man rights. Its primary aim is to publish volumes which off er interdisciplinary analysis of global societal problems, review past legal responses, and develop solutions which maximize access by all to the realization of universal human as- pirations. Other original studies in the fi eld of human rights are also considered for inclusion. The titles published in this series are listed at Brill.com/sihr Privacy in the 21st Century By Alexandra Rengel LEIDEN • BOSTON 2013 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rengel, Alexandra, author. Privacy in the 21st century / By Alexandra Rengel. p. cm. -- (Studies in intercultural human rights) Includes index. ISBN 978-90-04-19112-9 (hardback : alk. paper) -- ISBN 978-90-04-19219-5 (e-book) 1. Privacy, Right of. 2. International law. I. Title. II. Title: Privacy in the twenty-first century. K3263.R46 2013 342.08’58--dc23 2013037396 issn 1876-9861 isbn 978-90-04-19112-9 (hardback) isbn 978-90-04-19219-5 (e-book) Copyright 2013 by Koninklijke Brill nv, Leiden, The Netherlands. -

Searching for Privacy in a Mixed Jurisdiction

Searching for Privacy in a Mixed Jurisdiction Hector L. MacQueen* I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................... 73 II. PROTECTING PRIVACY IN SCOTS LAW TO 2000 .................................. 74 III. THE IMPACT OF DOMESTICATED HUMAN RIGHTS LAW ..................... 77 IV. SCOTS LAW: MAKING CHOICES......................................................... 83 A. Breach of Confidence............................................................... 84 B. The Actio Iniuriarum ................................................................ 88 V. ANALYSIS AND QUESTIONS................................................................. 94 VI. CONCLUSION ...................................................................................... 97 I. INTRODUCTION Reviewing A History of Private Law in Scotland in the Tulane Law Review in 2004, Shael Herman explained how the collection (published in 2000) left him with an impression of the “eclectic, open-textured character of Scots legal evolution”, even if sometimes he had a “a sense of having toured a juridical Australia or Galapagos Islands inhabited by exotic flora and fauna not found elsewhere”.1 He noted the complexity of the relationship between Scots and English law, and observed: To be sure, between Scotland and England there are striking political and cultural commonalities too numerous to detail. It could hardly be otherwise for two island nations that share a language, a currency, and a border. Yet, as the collection under review shows, -

Regulating Undercover Agents' Operations and Criminal

This document is downloaded from CityU Institutional Repository, Run Run Shaw Library, City University of Hong Kong. Regulating undercover agents’ operations and criminal Title investigations in Hong Kong: What lessons can be learnt from the United Kingdom and South Australia Author(s) Chen, Yuen Tung Eutonia (陳宛彤) Chen, Y. T. E. (2012). Regulating undercover agents’ operations and criminal investigations in Hong Kong: What lessons can be learnt Citation from the United Kingdom and South Australia (Outstanding Academic Papers by Students (OAPS)). Retrieved from City University of Hong Kong, CityU Institutional Repository. Issue Date 2012 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2031/6855 This work is protected by copyright. Reproduction or distribution of Rights the work in any format is prohibited without written permission of the copyright owner. Access is unrestricted. Page | 1 LW 4635 INDEPENDENT RESEARCH Topic: Regulating Undercover Agents’ Operations and Criminal Investigations in Hong Kong: What Lessons can be learnt from the United Kingdom and South Australia? Student Name: CHEN Yuen Tung Eutonia1 Date: 13th April 2012 Word Count: 9570 (excluding cover page, footnote and bibliography) Number of Pages: 39 Abstract It is not a dispute that undercover police officers have a proper role to play in contemporary law enforcement. However, there is no clear legislation in Hong Kong on the issue of whether the undercover agent is, at law, an offender of crime(s). This paper would examine the limitations of the prevailing undercover policing laws in Hong Kong and suggest possible recommendations. In particular, a comparative study of the United Kingdom and South Australia would be made to investigate whether Hong Kong should enact a legislation regulating undercover operations and criminal investigations. -

Risks and Rewards of the Anytime-Anywhere Internet Risks and Rewards of the Anytime-Anywhere Internet

Research Collection Monograph ON/OFF: Risks and Rewards of the Anytime-Anywhere Internet Risks and Rewards of the Anytime-Anywhere Internet Author(s): Genner, Sarah Publication Date: 2017 Permanent Link: https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-a-010805600 Originally published in: http://doi.org/10.3218/3800-2 Rights / License: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported This page was generated automatically upon download from the ETH Zurich Research Collection. For more information please consult the Terms of use. ETH Library ON | OFF Risks and Rewards of the Anytime-Anywhere Internet Sarah Genner This work was accepted as a PhD thesis by the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, University of Zurich in the spring semester 2016 on the recommendation of the Doctoral Committee: Prof. Dr. Daniel Sü ss (main supervisor, University of Zurich, Switzerland) and Prof. Dr. Urs Gasser (Harvard University, USA). Published with the support of the Swiss National Science Foundation. Bibliographic Information published by Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de. This work is licensed under Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-SA 3.0. Cover photo: fl ickr.com/photos/zuerichs-strassen © 2017, vdf Hochschulverlag AG an der ETH Zürich ISBN 978-3-7281-3799-9 (Print) ISBN 978-3-7281-3800-2 (Open Access) DOI 10.3218/3800-2 www.vdf.ethz.ch [email protected] Table of Contents Preface ................................................................................................................................... -

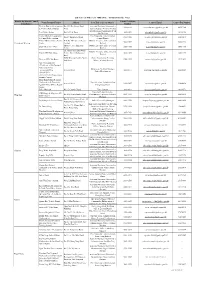

List of Access Officer (For Publication)

List of Access Officer (for Publication) - (Hong Kong Police Force) District (by District Council Contact Telephone Venue/Premise/FacilityAddress Post Title of Access Officer Contact Email Conact Fax Number Boundaries) Number Western District Headquarters No.280, Des Voeux Road Assistant Divisional Commander, 3660 6616 [email protected] 2858 9102 & Western Police Station West Administration, Western Division Sub-Divisional Commander, Peak Peak Police Station No.92, Peak Road 3660 9501 [email protected] 2849 4156 Sub-Division Central District Headquarters Chief Inspector, Administration, No.2, Chung Kong Road 3660 1106 [email protected] 2200 4511 & Central Police Station Central District Central District Police Service G/F, No.149, Queen's Road District Executive Officer, Central 3660 1105 [email protected] 3660 1298 Central and Western Centre Central District Shop 347, 3/F, Shun Tak District Executive Officer, Central Shun Tak Centre NPO 3660 1105 [email protected] 3660 1298 Centre District 2/F, Chinachem Hollywood District Executive Officer, Central Central JPC Club House Centre, No.13, Hollywood 3660 1105 [email protected] 3660 1298 District Road POD, Western Garden, No.83, Police Community Relations Western JPC Club House 2546 9192 [email protected] 2915 2493 2nd Street Officer, Western District Police Headquarters - Certificate of No Criminal Conviction Office Building & Facilities Manager, - Licensing office Arsenal Street 2860 2171 [email protected] 2200 4329 Police Headquarters - Shroff Office - Central Traffic Prosecutions Enquiry Counter Hong Kong Island Regional Headquarters & Complaint Superintendent, Administration, Arsenal Street 2860 1007 [email protected] 2200 4430 Against Police Office (Report Hong Kong Island Room) Police Museum No.27, Coombe Road Force Curator 2849 8012 [email protected] 2849 4573 Inspector/Senior Inspector, EOD Range & Magazine MT. -

Ethical Hacking

Ethical Hacking Alana Maurushat University of Ottawa Press ETHICAL HACKING ETHICAL HACKING Alana Maurushat University of Ottawa Press 2019 The University of Ottawa Press (UOP) is proud to be the oldest of the francophone university presses in Canada and the only bilingual university publisher in North America. Since 1936, UOP has been “enriching intellectual and cultural discourse” by producing peer-reviewed and award-winning books in the humanities and social sciences, in French or in English. Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Title: Ethical hacking / Alana Maurushat. Names: Maurushat, Alana, author. Description: Includes bibliographical references. Identifiers: Canadiana (print) 20190087447 | Canadiana (ebook) 2019008748X | ISBN 9780776627915 (softcover) | ISBN 9780776627922 (PDF) | ISBN 9780776627939 (EPUB) | ISBN 9780776627946 (Kindle) Subjects: LCSH: Hacking—Moral and ethical aspects—Case studies. | LCGFT: Case studies. Classification: LCC HV6773 .M38 2019 | DDC 364.16/8—dc23 Legal Deposit: First Quarter 2019 Library and Archives Canada © Alana Maurushat, 2019, under Creative Commons License Attribution— NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ Printed and bound in Canada by Gauvin Press Copy editing Robbie McCaw Proofreading Robert Ferguson Typesetting CS Cover design Édiscript enr. and Elizabeth Schwaiger Cover image Fragmented Memory by Phillip David Stearns, n.d., Personal Data, Software, Jacquard Woven Cotton. Image © Phillip David Stearns, reproduced with kind permission from the artist. The University of Ottawa Press gratefully acknowledges the support extended to its publishing list by Canadian Heritage through the Canada Book Fund, by the Canada Council for the Arts, by the Ontario Arts Council, by the Federation for the Humanities and Social Sciences through the Awards to Scholarly Publications Program, and by the University of Ottawa. -

2020 Cross-Border Corporate Criminal Liability Survey 2020 Cross-Border Corporate Criminal Liability Survey

2019 ANNUAL M&A REVIEW 2020 CROSS-BORDER CORPORATE CRIMINAL LIABILITY SURVEY 2020 CROSS-BORDER CORPORATE CRIMINAL LIABILITY SURVEY TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION . 1 MIDDLE EAST . 106 GLOSSARY . 4 ISRAEL . 107 AFRICA . 5 SAUDI ARABIA. 113 SOUTH AFRICA. .. 6 UNITED ARAB EMIRATES . 117 ASIA PACIFIC . 10 NORTH AMERICA . 121 AUSTRALIA . .11 CANADA . 122 CHINA . 16 MEXICO . 126 HONG KONG . 20 UNITED STATES . 131 INDIA . 25 SOUTH AMERICA . .. 135 INDONESIA . 30 ARGENTINA . 136 JAPAN . 34 BRAZIL . 141 SINGAPORE . 38 CHILE . 145 TAIWAN (REPUBLIC OF CHINA) . 43 VENEZUELA . 149 CENTRAL AMERICA . 47 CONTACTS . 152 COSTA RICA . 48 EUROPE . 52 BELGIUM . 53 FRANCE . 57 GERMANY . 62 ITALY . 69 NETHERLANDS. .. 76 RUSSIA . 84 SPAIN . 87 SWITZERLAND . 92 TURKEY . 96 UKRAINE . 99 UNITED KINGDOM . 103 Jones Day White Paper 2020 CROSS-BORDER CORPORATE CRIMINAL LIABILITY SURVEY INTRODUCTION For any company, the risk that employees or agents may countries, and the ability of industry participants to engage in criminal conduct in connection with their work assert (accurately or inaccurately) that a competitor has and thereby potentially expose the company (or at least broken the law . Multinational companies are at ever- the responsible individuals) to criminal, administrative, increasing risk of aggressive criminal enforcement, and/or civil liability is ever present; for multinational often across numerous jurisdictions at once . companies, which are necessarily subject to the laws To be sure, aggressive enforcement of corporate of multiple jurisdictions, this risk is only heightened . crime can help ensure that such crime is appropriately How a company manages the risk of corporate criminal punished and deterred and that the rights and interests liability, in particular, can not only determine its success, of victims are honored through a criminal proceeding . -

Volume 4, Number 2 2016

Volume 4, Number 2 2016 Salus Journal A peer-reviewed, open access journal for topics concerning law enforcement, national security, and emergency management Published by Charles Sturt University Australia ISSN 2202-5677 Editorial Board—Associate Editors Volume 4, Number 2, 2016 Dr Jeremy G Carter www.salusjournal.com Indiana University-Purdue University Dr Anna Corbo Crehan Charles Sturt University, Canberra Published by Dr Ruth Delaforce Griffith University, Queensland Charles Sturt University Australian Graduate School of Policing and Dr Garth den Heyer Security New Zealand Police PO Box 168 Dr Victoria Herrington Manly, New South Wales, Australia, 1655 Australian Institute of Police Management Dr Valerie Ingham ISSN 2202-5677 Charles Sturt University, Canberra Dr Stephen Marrin James Madison University, Virginia Dr Alida Merlo Advisory Board Indiana University of Pennsylvania Associate Professor Nicholas O’Brien (Chair) Dr Alexey D. Muraviev Professor Simon Bronitt Curtin University, Perth, Western Australia Professor Ross Chambers Dr Maid Pajevic Professor Mick Keelty APM, AO College 'Logos Center' Mostar, Mr Warwick Jones, BA MDefStudies Bosnia-Herzegovina Dr Felix Patrikeeff University of Adelaide, South Australia Dr Tim Prenzler Editor-in-Chief Griffith University, Queensland Dr Henry Prunckun Dr Suzanna Ramirez Charles Sturt University, Sydney University of Queensland Dr Susan Robinson Assistant Editor Charles Sturt University, Canberra Ms Kellie Smyth, BA, MApAnth, GradCert Dr Rick Sarre (LearnTeach in HigherEd) University of -

Seventh United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems, Table Comments by Country

UNITED NATIONS NATIONS UNIES Office on Drugs and Crime Division for Policy Analysis and Public Affairs Seventh United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems, covering the period 1998 - 2000 Comments by Table 1. Police personnel, by sex, and financial resources Alternative reference date to 31 December POLICE 1. Police personnel, by sex, and financial resources Alternative reference date to 31 December England & Wales 30 September Japan 1 April 2. Crimes recorded in criminal (police) statistics, by type of crime including attempts to commit crimes What is (are) the source(s) of the data provided in this table? Australia Recorded Crime Statistics 2000 (cat: 4510.0) Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Azerbaijan Reports on crimes Barbados Royal Barbados Police Force, Research and Development Department Bulgaria Ministry of Interior - Regular Report Canada Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics, Uniform Crime Report and Homicide Survey, Statistics Canada. Chile S.I.E.C (Sistema Integrado Estadistico de Carabineros) Colombia Policia Nacional, Direccion Central de Policia Judicial, Centro de Investigaciones Criminologicas Côte d'Ivoire Direction Centrale de la police Judiciaire Czech Republic Recording and Statistical System of Crime maintained by the Police of the Czech Republic Denmark Statistics of reported crimes, National Commissioner of Police, Department E. Dominica Criminal Records Office Friday, March 19, 2004 Page 1 of 22 2. Crimes recorded in criminal (police) statistics, by type of crime includi What is (are) the source(s) of the data provided in this table? England & Wales Recorded crime database Finland Statistics Finland: Yearbook of Justice Statistics (SVT) Georgia Ministry of Internal Affairs of Georgia.