Review: Recent Status of Selaginella (Selaginellaceae) Research in Nusantara

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RI Equisetopsida and Lycopodiopsida.Indd

IIntroductionntroduction byby FFrancisrancis UnderwoodUnderwood Rhode Island Equisetopsida, Lycopodiopsida and Isoetopsida Special Th anks to the following for giving permission for the use their images. Robbin Moran New York Botanical Garden George Yatskievych and Ann Larson Missouri Botanical Garden Jan De Laet, plantsystematics.org Th is pdf is a companion publication to Rhode Island Equisetopsida, Lycopodiopsida & Isoetopsida at among-ri-wildfl owers.org Th e Elfi n Press 2016 Introduction Formerly known as fern allies, Horsetails, Club-mosses, Fir-mosses, Spike-mosses and Quillworts are plants that have an alternate generation life-cycle similar to ferns, having both sporophyte and gametophyte stages. Equisetopsida Horsetails date from the Devonian period (416 to 359 million years ago) in earth’s history where they were trees up to 110 feet in height and helped to form the coal deposits of the Carboniferous period. Only one genus has survived to modern times (Equisetum). Horsetails Horsetails (Equisetum) have jointed stems with whorls of thin narrow leaves. In the sporophyte stage, they have a sterile and fertile form. Th ey produce only one type of spore. While the gametophytes produced from the spores appear to be plentiful, the successful reproduction of the sporophyte form is low with most Horsetails reproducing vegetatively. Lycopodiopsida Lycopodiopsida includes the clubmosses (Dendrolycopodium, Diphasiastrum, Lycopodiella, Lycopodium , Spinulum) and Fir-mosses (Huperzia) Clubmosses Clubmosses are evergreen plants that produce only microspores that develop into a gametophyte capable of producing both sperm and egg cells. Club-mosses can produce the spores either in leaf axils or at the top of their stems. Th e spore capsules form in a cone-like structures (strobili) at the top of the plants. -

WRA Species Report

Family: Selaginellaceae Taxon: Selaginella braunii Synonym: Lycopodioides braunii (Baker) Kuntze Common Name: arborvitae fern Selaginella braunii fo. hieronymi Alderw. Braun's spike-moss Selaginella hieronymi Alderw. Chinese lace-fern spike-moss Selaginella vogelii Mett. treelet spike-moss Questionaire : current 20090513 Assessor: Assessor Designation: H(HPWRA) Status: Assessor Approved Data Entry Person: Assessor WRA Score 7 101 Is the species highly domesticated? y=-3, n=0 n 102 Has the species become naturalized where grown? y=1, n=-1 103 Does the species have weedy races? y=1, n=-1 201 Species suited to tropical or subtropical climate(s) - If island is primarily wet habitat, then (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2- Low substitute "wet tropical" for "tropical or subtropical" high) (See Appendix 2) 202 Quality of climate match data (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2- High high) (See Appendix 2) 203 Broad climate suitability (environmental versatility) y=1, n=0 y 204 Native or naturalized in regions with tropical or subtropical climates y=1, n=0 n 205 Does the species have a history of repeated introductions outside its natural range? y=-2, ?=-1, n=0 y 301 Naturalized beyond native range y = 1*multiplier (see y Appendix 2), n= question 205 302 Garden/amenity/disturbance weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see n Appendix 2) 303 Agricultural/forestry/horticultural weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see n Appendix 2) 304 Environmental weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see n Appendix 2) 305 Congeneric weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see y Appendix 2) 401 Produces spines, thorns or -

Selaginellaceae: Traditional Use, Phytochemistry and Pharmacology

MS Editions BOLETIN LATINOAMERICANO Y DEL CARIBE DE PLANTAS MEDICINALES Y AROMÁTICAS 19 (3): 247 - 288 (2020) © / ISSN 0717 7917 / www.blacpma.ms-editions.cl Revisión | Review Selaginellaceae: traditional use, phytochemistry and pharmacology [Selaginellaceae: uso tradicional, fitoquímica y farmacología] Fernanda Priscila Santos Reginaldo, Isabelly Cristina de Matos Costa & Raquel Brandt Giordani College of Pharmacy, Pharmacy Department. University of Rio Grande do Norte, Natal, RN, Brazil. Contactos | Contacts: Raquel Brandt GIORDANI - E-mail address: [email protected] Abstract: Selaginella is the only genus from Selaginellaceae, and it is considered a key factor in studying evolution. The family managed to survive the many biotic and abiotic pressures during the last 400 million years. The purpose of this review is to provide an up-to-date overview of Selaginella in order to recognize their potential and evaluate future research opportunities. Carbohydrates, pigments, steroids, phenolic derivatives, mainly flavonoids, and alkaloids are the main natural products in Selaginella. A wide spectrum of in vitro and in vivo pharmacological activities, some of them pointed out by folk medicine, has been reported. Future studies should afford valuable new data on better explore the biological potential of the flavonoid amentoflavone and their derivatives as chemical bioactive entities; develop studies about toxicity and, finally, concentrate efforts on elucidate mechanisms of action for biological properties already reported. Keywords: Selaginella; Natural Products; Overview. Resumen: Selaginella es el único género de Selaginellaceae, y se considera un factor clave en el estudio de la evolución. La familia logró sobrevivir a las muchas presiones bióticas y abióticas durante los últimos 400 millones de años. -

Evidence-Based Medicinal Potential and Possible Role of Selaginella in the Prevention of Modern Chronic Diseases: Ethnopharmacological and Ethnobotanical Perspective

REVIEW ARTICLE Rec. Nat. Prod. X:X (2021) XX-XX Evidence-Based Medicinal Potential and Possible Role of Selaginella in the Prevention of Modern Chronic Diseases: Ethnopharmacological and Ethnobotanical Perspective Mohd Adnan 1*, Arif Jamal Siddiqui 1, Arshad Jamal 1, Walid Sabri Hamadou 1, Amir Mahgoub Awadelkareem 2, Manojkumar Sachidanandan 3 and Mitesh Patel 4 1Department of Biology, College of Science, University of Ha’il, Ha’il, P O Box 2440, Saudi Arabia 2Department of Clinical Nutrition, College of Applied Medial Sciences, University of Hail, Hail PO Box 2440, Saudi Arabia 3Department of Oral Radiology, College of Dentistry, University of Hail, Hail, PO Box 2440, Saudi Arabia 4Bapalal Vaidya Botanical Research Centre, Department of Biosciences, Veer Narmad South Gujarat University, Surat, Gujarat, India (Received November 26, 2020; Revised January 29, 2021; Accepted January 31, 2021) Abstract: Different species of the genus Selaginella are exploited for various ethnomedicinal purposes around the globe; mainly to cure fever, jaundice, hepatic disorders, cardiac diseases, cirrhosis, diarrhea, cholecystitis, sore throat, cough of lungs, promotes blood circulation, removes blood stasis and stops external bleeding after trauma and separation of the umbilical cord. Though, high content of various phytochemicals has been isolated from Selaginella species, flavonoids have been recognized as the most active component in the genus. Crude extract and different bioactive compounds of this plant have revealed various in vitro bioactivities such as, antimicrobial, antiviral, anti-diabetic, anti-mutagenic, anti-inflammatory, anti-nociceptive, anti-spasmodic, anticancer and anti-Alzheimer. However, more studies into the pharmacological activities are needed, since none of the professed bioactivity of this plant have ever been fully evaluated. -

Biological Survey of a Prairie Landscape in Montana's Glaciated

Biological Survey of a Prairie Landscape in Montanas Glaciated Plains Final Report Prepared for: Bureau of Land Management Prepared by: Stephen V. Cooper, Catherine Jean and Paul Hendricks December, 2001 Biological Survey of a Prairie Landscape in Montanas Glaciated Plains Final Report 2001 Montana Natural Heritage Program Montana State Library P.O. Box 201800 Helena, Montana 59620-1800 (406) 444-3009 BLM Agreement number 1422E930A960015 Task Order # 25 This document should be cited as: Cooper, S. V., C. Jean and P. Hendricks. 2001. Biological Survey of a Prairie Landscape in Montanas Glaciated Plains. Report to the Bureau of Land Management. Montana Natural Heritage Pro- gram, Helena. 24 pp. plus appendices. Executive Summary Throughout much of the Great Plains, grasslands limited number of Black-tailed Prairie Dog have been converted to agricultural production colonies that provide breeding sites for Burrow- and as a result, tall-grass prairie has been ing Owls. Swift Fox now reoccupies some reduced to mere fragments. While more intact, portions of the landscape following releases the loss of mid - and short- grass prairie has lead during the last decade in Canada. Great Plains to a significant reduction of prairie habitat Toad and Northern Leopard Frog, in decline important for grassland obligate species. During elsewhere, still occupy some wetlands and the last few decades, grassland nesting birds permanent streams. Additional surveys will have shown consistently steeper population likely reveal the presence of other vertebrate declines over a wider geographic area than any species, especially amphibians, reptiles, and other group of North American bird species small mammals, of conservation concern in (Knopf 1994), and this alarming trend has been Montana. -

Comparative Transcriptome Analysis Suggests Convergent Evolution Of

Alejo-Jacuinde et al. BMC Plant Biology (2020) 20:468 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-020-02638-3 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Comparative transcriptome analysis suggests convergent evolution of desiccation tolerance in Selaginella species Gerardo Alejo-Jacuinde1,2, Sandra Isabel González-Morales3, Araceli Oropeza-Aburto1, June Simpson2 and Luis Herrera-Estrella1,4* Abstract Background: Desiccation tolerant Selaginella species evolved to survive extreme environmental conditions. Studies to determine the mechanisms involved in the acquisition of desiccation tolerance (DT) have focused on only a few Selaginella species. Due to the large diversity in morphology and the wide range of responses to desiccation within the genus, the understanding of the molecular basis of DT in Selaginella species is still limited. Results: Here we present a reference transcriptome for the desiccation tolerant species S. sellowii and the desiccation sensitive species S. denticulata. The analysis also included transcriptome data for the well-studied S. lepidophylla (desiccation tolerant), in order to identify DT mechanisms that are independent of morphological adaptations. We used a comparative approach to discriminate between DT responses and the common water loss response in Selaginella species. Predicted proteomes show strong homology, but most of the desiccation responsive genes differ between species. Despite such differences, functional analysis revealed that tolerant species with different morphologies employ similar mechanisms to survive desiccation. Significant functions involved in DT and shared by both tolerant species included induction of antioxidant systems, amino acid and secondary metabolism, whereas species-specific responses included cell wall modification and carbohydrate metabolism. Conclusions: Reference transcriptomes generated in this work represent a valuable resource to study Selaginella biology and plant evolution in relation to DT. -

Desiccation Tolerance: Phylogeny and Phylogeography

Desiccation Tolerance: Phylogeny and Phylogeography BioQUEST Workshop 2009 Resurrection Plants Desiccation tolerant Survive dehydration Survive in dormant state for extended time period Survive rehydration Xerophyta humilis, from J. Farrant web site (http://www.mcb.uct.ac.za/Staff/JMF/index.htm) Figure 2. Selaginella lepidophylla http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ File:Rose_of_Jericho.gif Desiccation Issues Membrane integrity Protein structure Generation of free radicals Rascia, N, La Rocca, N. 2005 Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences Solutions Repair upon hydration Prevent damage during dehydration Production/accumulation of replacement solutes Inhibition of photosynthesis http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/staff/dave/roanoke/elodeacell.jpg Evolution of Desiccation Tolerance From Oliver, et al 2000. Plant Ecology Convergent Evolution Among Vascular Plants From Oliver, et al 2000. Plant Ecology Desiccation Tolerance in Vascular Plants Seeds Pollen Spores Osmotic stress Desertification 40% of Earth’s surface 38% of population Low productivity Lack of water Depletion of soil Loss of soil Delicate system Using Evolutionary Relationships to Identify Genes for Crop Enhancement If desiccation sensitive plants have retained genes involved in desiccation tolerance, perhaps expression of those genes can be genetically modified to enhance desiccation tolerance. Expression patterns in dehydratingTortula and Xerophyta Michael Luth Xerophyta humilis, from J. Farrant web site (http://www.mcb.uct.ac.za/Staff/JMF/index.htm) ? Methods Occurrence data for Anastatica hierochuntic: o Downloaded from the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (gbif.org). o Of 127 available occurrence points, only 68 were georeferenced with latitude and longitude information. Environmental layers: Precipitation and temperature from the IPCC climate dataset Niche Modeling: Maximum Entropy (Maxent) Maxent principle is to estimate the probability distribution such as the spatial distribution of a species. -

Maine's Endangered and Threatened Plants

University of Southern Maine USM Digital Commons Maine Collection 1990 Maine's Endangered and Threatened Plants Maine State Planning Office Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/me_collection Part of the Biodiversity Commons, Botany Commons, Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, Forest Biology Commons, Forest Management Commons, Other Forestry and Forest Sciences Commons, Plant Biology Commons, and the Weed Science Commons Recommended Citation Maine State Planning Office, "Maine's Endangered and Threatened Plants" (1990). Maine Collection. 49. https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/me_collection/49 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by USM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine Collection by an authorized administrator of USM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BACKGROUND and PURPOSE In an effort to encourage the protection of native Maine plants that are naturally reduced or low in number, the State Planning Office has compiled a list of endangered and threatened plants. Of Maine's approximately 1500 native vascular plant species, 155, or about 10%, are included on the Official List of Maine's Plants that are Endangered or Threatened. Of the species on the list, three are also listed at the federal level. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. has des·ignated the Furbish's Lousewort (Pedicularis furbishiae) and Small Whorled Pogonia (lsotria medeoloides) as Endangered species and the Prairie White-fringed Orchid (Platanthera leucophaea) as Threatened. Listing rare plants of a particular state or region is a process rather than an isolated and finite event. -

Chapter 23: the Early Tracheophytes

Chapter 23 The Early Tracheophytes THE LYCOPHYTES Lycopodium Has a Homosporous Life Cycle Selaginella Has a Heterosporous Life Cycle Heterospory Allows for Greater Parental Investment Isoetes May Be the Only Living Member of the Lepidodendrid Group THE MONILOPHYTES Whisk Ferns Ophioglossalean Ferns Horsetails Marattialean Ferns True Ferns True Fern Sporophytes Typically Have Underground Stems Sexual Reproduction Usually Is Homosporous Fern Have a Variety of Alternative Means of Reproduction Ferns Have Ecological and Economic Importance SUMMARY PLANTS, PEOPLE, AND THE ENVIRONMENT: Sporophyte Prominence and Survival on Land PLANTS, PEOPLE, AND THE ENVIRONMENT: Coal, Smog, and Forest Decline THE OCCUPATION OF THE LAND PLANTS, PEOPLE, AND THE The First Tracheophytes Were ENVIRONMENT: Diversity Among the Ferns Rhyniophytes Tracheophytes Became Increasingly Better PLANTS, PEOPLE, AND THE Adapted to the Terrestrial Environment ENVIRONMENT: Fern Spores Relationships among Early Tracheophytes 1 KEY CONCEPTS 1. Tracheophytes, also called vascular plants, possess lignified water-conducting tissue (xylem). Approximately 14,000 species of tracheophytes reproduce by releasing spores and do not make seeds. These are sometimes called seedless vascular plants. Tracheophytes differ from bryophytes in possessing branched sporophytes that are dominant in the life cycle. These sporophytes are more tolerant of life on dry land than those of bryophytes because water movement is controlled by strongly lignified vascular tissue, stomata, and an extensive cuticle. The gametophytes, however still require a seasonally wet habitat, and water outside the plant is essential for the movement of sperm from antheridia to archegonia. 2. The rhyniophytes were the first tracheophytes. They consisted of dichotomously branching axes, lacking roots and leaves. They are all extinct. -

Native Plant List CITY of OREGON CITY 320 Warner Milne Road , P.O

Native Plant List CITY OF OREGON CITY 320 Warner Milne Road , P.O. Box 3040, Oregon City, OR 97045 Phone: (503) 657-0891, Fax: (503) 657-7892 Scientific Name Common Name Habitat Type Wetland Riparian Forest Oak F. Slope Thicket Grass Rocky Wood TREES AND ARBORESCENT SHRUBS Abies grandis Grand Fir X X X X Acer circinatumAS Vine Maple X X X Acer macrophyllum Big-Leaf Maple X X Alnus rubra Red Alder X X X Alnus sinuata Sitka Alder X Arbutus menziesii Madrone X Cornus nuttallii Western Flowering XX Dogwood Cornus sericia ssp. sericea Crataegus douglasii var. Black Hawthorn (wetland XX douglasii form) Crataegus suksdorfii Black Hawthorn (upland XXX XX form) Fraxinus latifolia Oregon Ash X X Holodiscus discolor Oceanspray Malus fuscaAS Western Crabapple X X X Pinus ponderosa Ponderosa Pine X X Populus balsamifera ssp. Black Cottonwood X X Trichocarpa Populus tremuloides Quaking Aspen X X Prunus emarginata Bitter Cherry X X X Prunus virginianaAS Common Chokecherry X X X Pseudotsuga menziesii Douglas Fir X X Pyrus (see Malus) Quercus garryana Garry Oak X X X Quercus garryana Oregon White Oak Rhamnus purshiana Cascara X X X Salix fluviatilisAS Columbia River Willow X X Salix geyeriana Geyer Willow X Salix hookerianaAS Piper's Willow X X Salix lucida ssp. lasiandra Pacific Willow X X Salix rigida var. macrogemma Rigid Willow X X Salix scouleriana Scouler Willow X X X Salix sessilifoliaAS Soft-Leafed Willow X X Salix sitchensisAS Sitka Willow X X Salix spp.* Willows Sambucus spp.* Elderberries Spiraea douglasii Douglas's Spiraea Taxus brevifolia Pacific Yew X X X Thuja plicata Western Red Cedar X X X X Tsuga heterophylla Western Hemlock X X X Scientific Name Common Name Habitat Type Wetland Riparian Forest Oak F. -

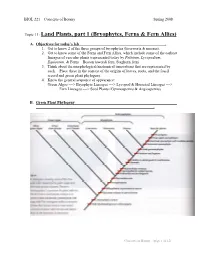

Topic 11: Land Plants, Part 1 (Bryophytes, Ferns & Fern Allies)

BIOL 221 – Concepts of Botany Spring 2008 Topic 11: Land Plants, part 1 (Bryophytes, Ferns & Fern Allies) A. Objectives for today’s lab . 1. Get to know 2 of the three groups of bryophytes (liverworts & mosses). 2. Get to know some of the Ferns and Fern Allies, which include some of the earliest lineages of vascular plants (represented today by Psilotum, Lycopodium, Equisetum, & Ferns—Boston (sword) fern, Staghorn fern) 3. Think about the morphological/anatomical innovations that are represented by each. Place these in the context of the origins of leaves, roots, and the fossil record and green plant phylogeny. 4. Know the general sequence of appearance: Green Algae ==> Bryophyte Lineages ==> Lycopod & Horsetail Lineages ==> Fern Lineages ==> Seed Plants (Gymnosperms & Angiosperms) B. Green Plant Phylogeny . Concepts of Botany, (page 1 of 12) C. NonVascular Free-Sporing Land Plants (Bryophytes) . C1. Liverworts . a. **LIVING MATERIAL**: Marchantia &/or Conacephalum (thallose liverworts). The conspicuous green plants are the gametophytes. With a dissecting scope, observe the polygonal outlines of the air chambers. On parts of the thallus are drier, it is easy to see the pore opening to the chamber. These are not stomata. They cannot open and close and the so the thallus can easily dry out if taking from water. Note the gemmae cups on some of that thalli. Ask your instructor what these are for. DRAW THEM TOO. b. **SLIDES**. Using the compound microscope, make observations of the vegetative and reproductive parts of various liverwort species. Note the structure of the air-chambers and the photosynthetic cells inside on the Marchantia sections! Concepts of Botany, (page 2 of 12) C2. -

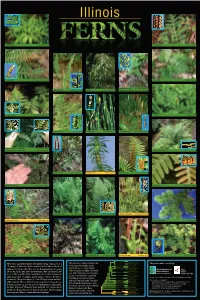

The Ferns and Their Relatives (Lycophytes)

N M D R maidenhair fern Adiantum pedatum sensitive fern Onoclea sensibilis N D N N D D Christmas fern Polystichum acrostichoides bracken fern Pteridium aquilinum N D P P rattlesnake fern (top) Botrychium virginianum ebony spleenwort Asplenium platyneuron walking fern Asplenium rhizophyllum bronze grapefern (bottom) B. dissectum v. obliquum N N D D N N N R D D broad beech fern Phegopteris hexagonoptera royal fern Osmunda regalis N D N D common woodsia Woodsia obtusa scouring rush Equisetum hyemale adder’s tongue fern Ophioglossum vulgatum P P P P N D M R spinulose wood fern (left & inset) Dryopteris carthusiana marginal shield fern (right & inset) Dryopteris marginalis narrow-leaved glade fern Diplazium pycnocarpon M R N N D D purple cliff brake Pellaea atropurpurea shining fir moss Huperzia lucidula cinnamon fern Osmunda cinnamomea M R N M D R Appalachian filmy fern Trichomanes boschianum rock polypody Polypodium virginianum T N J D eastern marsh fern Thelypteris palustris silvery glade fern Deparia acrostichoides southern running pine Diphasiastrum digitatum T N J D T T black-footed quillwort Isoëtes melanopoda J Mexican mosquito fern Azolla mexicana J M R N N P P D D northern lady fern Athyrium felix-femina slender lip fern Cheilanthes feei net-veined chain fern Woodwardia areolata meadow spike moss Selaginella apoda water clover Marsilea quadrifolia Polypodiaceae Polypodium virginanum Dryopteris carthusiana he ferns and their relatives (lycophytes) living today give us a is tree shows a current concept of the Dryopteridaceae Dryopteris marginalis is poster made possible by: { Polystichum acrostichoides T evolutionary relationships among Onocleaceae Onoclea sensibilis glimpse of what the earth’s vegetation looked like hundreds of Blechnaceae Woodwardia areolata Illinois fern ( green ) and lycophyte Thelypteridaceae Phegopteris hexagonoptera millions of years ago when they were the dominant plants.