Exhibition 01 Dec 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Online Cultural Mobility Funding Guide for AFRICA

An online cultural mobility funding guide for AFRICA — by ART MOVES AFRICA – Research INSTITUT FRANÇAIS – Support ON THE MOVE – Coordination Third Edition — Suggestions for reading this guide: We recommend that you download the guide and open it using Acrobat Reader. You can then click on the web links and consult the funding schemes and resources. Alterna- tively, you can also copy and paste the web links of the schemes /resources that interest you in your browser’s URL field. This guide being long, we advise you not to print it, especially since all resources are web-based. Thank you! Guide to funding opportunities for the international mobility of artists and culture professionals: AFRICA — An online cultural mobility funding guide for Africa by ART MOVES AFRICA – Research INSTITUT FRANÇAIS – Support ON THE MOVE – Coordination design by Eps51 December 2019 — GUIDE TO FUNDING OPPORTUNITIES FOR THE INTERNATIONAL MOBILITY OF ARTISTS AND CULTURE PROFESSIONALS – AFRICA Guide to funding opportunities for the international This Cultural Mobility Funding Guide presents a mapping of mobility of funding opportunities for interna- tional cultural mobility, focused artists and culture on the African continent. professionals The main objective of this cul- tural mobility funding guide is to AFRICA provide an overview of the fund- ing bodies and programmes that support the international mobility of artists and cultural operators from Africa and travelling to Africa. It also aims to provide input for funders and policy makers on how to fill the existing -

213-447-8229

STACY KRANITZ [email protected] www.stacykranitz.com/ 213-447-8229 EDUCATION: University of California, Irvine, MFA, Department of Art New York University, BA, Gallatin School of Individualized Study GRANTS AND 2020 Guggenheim Fellowship AWARDS Southern Documentary Fund Research and Development Grant We Women Grant Magnum Foundation Fund: US Dispatches National Geographic Grant for Journalists Ella Lyman Cabot Trust Grant 2019 Great Smoky Mountain National Park, Artist in Residence Crosstown Arts Residency Program 2017 Michael P. Smith Fund for Documentary Photography Columbus State University, Artist in Residence 2015 Time Magazine Instagram Photographer of the Year The Hambidge Center for the Creative Arts & Sciences, Artist in Residence 2014 Gallery Protocol 2013 Editorial Photographer Education Grant, American Photographic Arts 2012 Research/Travel Grant, Claire Trevor School of the Arts, University of California, Irvine 2010 Young Photographers Alliance Scholarship Award, Worldstudio AIGA SOLO 2019 As it Was Give(n) To Me, Tracey Morgan Gallery, Asheville, NC EXHIBITIONS: As it Was Give(n) To Me, Les Rencontres de la Photografie, Arles, France 2018 As it Was Give(n) To Me, Marfa Open 18, Marfa, TX 2017 Fulcrum of Malice, Tracey Morgan Gallery, Asheville, NC The Great Divide by Stacy Kranitz and Zoe Strauss, Lightfield Festival, Hudson, NY 2015 As it Was Give(n) to Me, Diffusion, Cardiff International Festival of Photography, Wales, UK From the Study on Post Pubescent Manhood, Little Big Man Gallery, Los Angeles, CA 2014 Once -

Limited Edition Platinum Prints of Iconic Images by Robert Capa

PRESS RELEASE Contact : Amy Wentz Ruder Finn Arts & Communications Counselors [email protected] / 212-715-1551 Limited Edition Platinum Prints of Iconic Images by Robert Capa, Henri Cartier-Bresson, George Rodger and David Seymour to be Published in Unique Hand-Bound Collector’s Book Magnum Founders, In Celebration of Sixty Years Provides Collectors Once-in-a-Lifetime Opportunity to Own Part of Photographic History Santa Barbara, California, June 6, 2007 – Verso Limited Editions, a publisher of handcrafted books that celebrate the work of significant photographers, announced the September 2007 publication of Magnum Founders, In Celebration of Sixty Years . Magnum Founders will include twelve bound and one free-standing rare platinum, estate-stamped prints of iconic images by four visionary photographers who influenced the course of modern photographic history – Robert Capa, Henri Cartier-Bresson, George Rodger and David “Chim” Seymour. The collector’s book celebrates the 60 th anniversary of Magnum Photos, a photographic co- operative founded by these four men and owned by its photographer-members. Capa, Cartier- Bresson, Rodger and Seymour created Magnum in 1947 to reflect their independent natures as both people and photographers – the idiosyncratic mix of reporter and artist that continues to define Magnum today. The first copy of Magnum Founders will be privately unveiled on Thursday, June 21 at the Museum of Modern Art, New York – birthplace of Magnum Photos – during the “Magnum Festival,” a month-long series of events celebrating the art of documentary photography. Magnum Founders will also be on view to the public at the Howard Greenberg Gallery, 41 East 52 nd St., New York, beginning on Friday, June 22. -

Our Choice of New and Emerging Photographers to Watch

OUR CHOICE OF NEW AND EMERGING PHOTOGRAPHERS TO WATCH TASNEEM ALSULTAN SASHA ARUTYUNOVA XYZA BACANI IAN BATES CLARE BENSON ADAM BIRKAN KAI CAEMMERER NICHOLAS CALCOTT SOUVID DATTA RONAN DONOVAN BENEDICT EVANS PETER GARRITANO SALWAN GEORGES JUAN GIRALDO ERIC HELGAS CHRISTINA HOLMES JUSTIN KANEPS YUYANG LIU YAEL MARTINEZ PETER MATHER JAKE NAUGHTON ADRIANE OHANESIAN CAIT OPPERMANN KATYA REZVAYA AMANDA RINGSTAD ANASTASIIA SAPON ANDY J. SCOTT VICTORIA STEVENS CAROLYN VAN HOUTEN DANIELLA ZALCMAN © JUSTIN KANEPS APRIL 2017 pdnonline.com 25 OUR CHOICE OF NEW AND EMERGING PHOTOGRAPHERS TO WATCH EZVAYA R © KATYA © KATYA EDITor’s NoTE Reading about the burgeoning careers of these 30 Interning helped Carolyn Van Houten learn about working photographers, a few themes emerge: Personal, self- as a photographer; the Missouri Photo Workshop helped assigned work remains vital for photographers; workshops, Ronan Donovan expand his storytelling skills; Souvid fellowships, competitions and other opportunities to engage Datta gained recognition through the IdeasTap/Magnum with peers and mentors in the photo community are often International Photography Award, and Daniella Zalcman’s pivotal in building knowledge and confidence; and demeanor grants from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting altered and creative problem solving ability keep clients calling back. the course of her career. Many of the 2017 PDN’s 30 gained recognition by In their assignment work, these photographers deliver pursuing projects that reflect their own experiences and for their clients without fuss. Benedict Evans, a client interests. Salwan Georges explored the Iraqi immigrant says, “set himself apart” because people like to work with community of which he’s a part. Xyza Bacani, a one- him. -

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

The Ninth Hour A Novel Alice McDermott A portrait of the Irish-American experience by the National Book Award-winning author On a dim winter afternoon, a young Irish immigrant opens the gas taps in his Brooklyn tenement. He is determined to prove—to the subway bosses who have recently fired him, to his badgering, pregnant wife—“that the hours of his life belong to himself alone.” In the aftermath of the fire that follows, Sister St. Savior, an aging nun, a Little Sister of the Sick Poor, appears, unbidden, to direct the way forward for his widow and his unborn child. In Catholic Brooklyn, in the early part of the twentieth century, decorum, FICTION superstition, and shame collude to erase the man’s brief existence, and yet his suicide, although never spoken of, reverberates through many Farrar, Straus and Giroux | 9/19/2017 lives—testing the limits and the demands of love and sacrifice, of 9780374280147 | $26.00 Hardcover | 256 pages forgiveness and forgetfulness, even through multiple generations. Carton Qty: 24 | 8.3 in H | 5.5 in W Rendered with remarkable lucidity and intelligence, Alice McDermott’s Brit., trans., 1st ser., dram.: The Gernert Co. The Ninth Hour is a crowning achievement of one of the finest American Audio: FSG writers at work today. MARKETING Alice McDermott is the author of seven previous novels, including After This; Child of My Heart; Charming Billy, winner of the 1998 National Book Award; At Author Tour Weddings and Wakes; and Someone—all published by FSG. That Night, At National Publicity Weddings and Wakes, and After This were all finalists for the Pulitzer Prize. -

32E FESTIVAL INTERNATIONAL DU FILM DE LA ROCHELLE 25 JUIN – 5 JUILLET 2004

32e FESTIVAL INTERNATIONAL DU FILM DE LA ROCHELLE 25 JUIN – 5 JUILLET 2004 PRÉSIDENT Jacques Chavier DÉLÉGUÉE GÉNÉRALE Prune Engler DIRECTION ARTISTIQUE Prune Engler Sylvie Pras assistées de Sophie Mirouze ADMINISTRATION Arnaud Dumatin CHARGÉ DE MISSION LA ROCHELLE Stéphane Le Garff assisté d’Aurélie Morand CHARGÉ DE MISSION CHINE Feng Xu DIRECTION TECHNIQUE Pierre-Jean Bouyer COMPTABILITÉ Monique Savinaud PRESSE matilde incerti assistée de Hervé Dupont PROGRAMMATION VIDÉO en partenariat avec Transat Vidéo Brent Klinkum PUBLICATIONS Anne Berrou Caroline Maleville assistées d’Armelle Bayou MAQUETTE Olivier Dechaud TRADUCTIONS Brent Klinkum SITE INTERNET Nicolas Le Thierry d’Ennequin AFFICHE DU FESTIVAL Stanislas Bouvier PHOTOGRAPHIES Régis d’Audeville HÉBERGEMENT Aurélie Morand STAGIAIRES Clara de Margerie Marion Ducamp Cécile Teuma BUREAU DU FESTIVAL (PARIS) 16 rue Saint-Sabin 75011 Paris Tél. : 01 48 06 16 66 Fax : 01 48 06 15 40 Email : [email protected] Site internet : www.festival-larochelle.org BUREAU DU FESTIVAL (LA ROCHELLE) Tél. et Fax : 05 46 52 28 96 Email : [email protected] Avec la collaboration de toute l’équipe de La Coursive, Scène Nationale La Rochelle L’année dernière à La Rochelle Anja Breien Hommage Serge Bromberg Retour de flamme Régis d’Audeville 2 Photographies Luis Ortega La Caja negra Jacques Baratier Rien voilà l’ordre Djamila Sahraoui Algérie, la vie quand même et Algérie, la vie toujours L’année dernière à La Rochelle Gilles Marchand Qui a tué Bambi ? Nicolas Philibert Hommage, et les -

Book XVIII Prizes and Organizations Editor: Ramon F

8 88 8 88 Organizations 8888on.com 8888 Basic Photography in 180 Days Book XVIII Prizes and Organizations Editor: Ramon F. aeroramon.com Contents 1 Day 1 1 1.1 Group f/64 ............................................... 1 1.1.1 Background .......................................... 2 1.1.2 Formation and participants .................................. 2 1.1.3 Name and purpose ...................................... 4 1.1.4 Manifesto ........................................... 4 1.1.5 Aesthetics ........................................... 5 1.1.6 History ............................................ 5 1.1.7 Notes ............................................. 5 1.1.8 Sources ............................................ 6 1.2 Magnum Photos ............................................ 6 1.2.1 Founding of agency ...................................... 6 1.2.2 Elections of new members .................................. 6 1.2.3 Photographic collection .................................... 8 1.2.4 Graduate Photographers Award ................................ 8 1.2.5 Member list .......................................... 8 1.2.6 Books ............................................. 8 1.2.7 See also ............................................ 9 1.2.8 References .......................................... 9 1.2.9 External links ......................................... 12 1.3 International Center of Photography ................................. 12 1.3.1 History ............................................ 12 1.3.2 School at ICP ........................................ -

Un Film De Yousry Nasrallah

l’aquarium un film de YousrY nasrallah Samedi 13 décembre 2008 à 22.40 l’aquarium un film de YousrY nasrallah Samedi 13 décembre 2008 à 22.40 au Caire, aujourd’hui, l’histoire d’une rencontre Le matin, il travaille dans un respectable hôpital entre deux êtres que tout rapproche. une privé. Le soir, dans une clinique clandestine où l’on vision acerbe de l’egypte contemporaine, un pratique l’avortement. Son père souffre d’un cancer pays gouverné par la peur, règne de toutes les en phase terminale et se trouve hospitalisé. Youssef hypocrisies.... aime écouter les délires de ses patients, juste avant qu’ils ne s’endorment. Et il aime leur raconter en Le film se déroule sur 48 heures. Au Caire. De nos détail ce qu’ils ont dit. Il aime aussi écouter l’émission jours. Laila, la trentaine, travaille à la radio. Elle y de Laila. Parfois, il passe une partie de la nuit chez anime l’émission « Secrets de Nuit » où les auditeurs une femme qu’il aime bien, mais pas au point de l’appellent pour lui parler de leurs vies amoureuses. passer toute la nuit chez elle. Il vit beaucoup dans Elle pratique le squash et la natation. Elle écrit des sa voiture. petits contes pour enfants. Parfois elle emmène les Deux personnages qui ne se connaissent pas, et enfants de sa meilleure amie au cirque, et parfois elle qui finiront par se rencontrer. Leurs vies ne vont pas retrouve ses amis dans une discothèque branchée changer. Mais peut-être réaliseront-ils à quel point au Caire. -

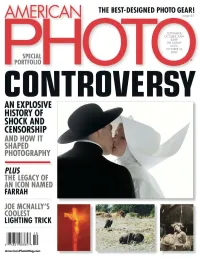

An Explosive History of Shock and Censorship and How It Shaped Photography

THE BEST-DESIGNED PHOTO GEAR! page 45 SEPTEMBER/ OCTOBER 2009 $4.99 ON DISPLAY UNTIL OCTOBER 19, SPECIAL 2009 COPORTFOLIONTROVERSY AN EXPLOSIVE HISTORY OF SHOCK AND CENSORSHIP AND HOW IT SHAPED PHOTOGRAPHY PLUS THE LEGACY OF AN ICON NAMED FARRAH JOE MCNALLY’S COOLEST LIGHTING TRICK AmericanPhotoMag.com TM November 13 – 15, 2009 © Eric Foltz othing captures the spirit of the American West like desert sunsets, Next we’ll crank the way-back machine and give you a glimpse of the Ngeological wonders and Old West gunfights. Saddle up for a memorable Old West through the lens of the film industry. At the base of the Tucson trek through the Sonoran Desert as the Mentor Series discovers the vast beau- Mountains lies the Old Tucson Studios, where such classics as “Gunfight ty and intricate curiosities of Tucson, Arizona. From panoramic, sun-drenched at the O.K. Corral,” “3:10 to Yuma,” and “The Lone Ranger and the Lost horizons to hidden locations the sun has never reached, you’ll discover the City of Gold” were filmed. Now restored, the same sets and streets where true extremes of light and dark. such legends as John Wayne and Clint Eastwood faced off with bad guys We’ll head to Gates Pass, revered by professional photographers world- is a piece of living history. A live cast of character, complete with brilliantly wide. It offers a vantage point unmatched for dazzling images of the setting colored costumes, will recreate stunts and shootouts that will challenge your sun. If you’ve ever had a “sunset screensaver,” it’s likely that the images fea- shutter speed and your reaction times. -

The Visual Culture of Human Rights: the Syrian Refugee Crisis

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Spring 2016 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Spring 2016 The Visual Culture of Human Rights: The Syrian Refugee Crisis Claudia Anne Mae Bennett Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2016 Part of the Photography Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Bennett, Claudia Anne Mae, "The Visual Culture of Human Rights: The Syrian Refugee Crisis" (2016). Senior Projects Spring 2016. 146. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2016/146 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Visual Culture of Human Rights: The Syrian Refugee Crisis Senior Project Submitted to The Division of Arts & Social Studies of Bard College by Claudia Bennett Annandale-on-Hudson, New York May 2016 Dedication To all refugees around the world I hope that you find a stable home, and that the events that sent you away from your nation end soon. And to all the heroes photographing the tragedies of our times, know that what you are doing is recognized by and inspiring to many. -

One-Year Certificate Programs 2016-2017 General Studies In

ONE-YEAR CERTIFICATE PROGRAMS 2016-2017 GENERAL STUDIES IN PHOTOGRAPHY DOCUMENTARY PHOTOGRAPHY AND PHOTOJOURNALISM NEW MEDIA NARRATIVES © Fernanda Lenz GS13 COVER © Jiaxi Yang GS15 2 1 CONTENTS One-Year Certificate Programs Letter from the Executive Director 5 Letter from the Dean 7 About the International Center of Photography 9 One-Year Certificate Programs Overview 11 Academic Calendar 13 General Studies in Photography Letter from the Chair 15 Course Outline 21 Alumni and Faculty Q&As 25 Documentary Photography and Photojournalism Letter from the Chair 33 Course Outline 37 Alumni Q&As 45 New Media Narratives Letter from the Chair 51 Course Outline 53 Q&A with the Chair 57 Chairs and Faculty 59 Facilities and Resources 63 Tuition, Fees, and Financial Aid 67 Admissions 71 International Students 71 © Sara Skorgan Teigen GS12 2 16/173 LETTER FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR This is an extraordinary moment in the history of photography and image making, as well as in the history of the International Center of Photography. ICP’s founder, Cornell Capa, described photography as “the most vital, effective, and universal means of communication of facts and ideas.” The power of images to cross barriers of language, geography, and culture is greater today than ever before. And in an era of profound change in the way images are made and interpreted, ICP remains the leading forum for provocative ideas, innovation, and debate. As the evolution of image making continues, ICP is expanding to meet new opportunities, with a dynamic new museum space on the Bowery in Manhattan and an expansive new collections facility at Mana Contemporary in Jersey City. -

Shifting Perceptions – Who Shapes the Image in the Photojournalistic Apparatus?

University of the Arts London London College of Communication MA Photojournalism and Documentary Photography (PT) 2019 Unit 2 / History of Photojournalism and Documentary Photography Course leader: Lewis Bush Shifting perceptions – Who shapes the image in the photojournalistic apparatus? A case study of the winning 2006 World Press Photo of the Year “Affluent Lebanese drive down the street to look at a destroyed neighbourhood 15 August 2006 in southern Beirut, Lebanon.” Critical essay submitted by: Jens Schwarz www.jensschwarz.com Table of contents 1. Introduction 2. Deconstructing the interpretativ layers of the photograph (expectations and perceptions) 2.1 Essential facts on date and place of the depicted scene (background) 2.2 What the photographer believes to see (production) 2.3 What the commissioning agency uses the image to ‘report’ (distribution) 2.4 What the World Press Photo contest jury judges to see (awarding) 2.5 What the (seemingly) accidentally mislead viewer is accusing the depicted persons to disrespect (ethical projections) 2.6 What the audience expects to see (reception) 2.7 What other involved war photographers expect to see in this type of imagery (competitors) 2.8 What actually happened (contextualisation) 3. Conclusion Appendix Bibliography Jens Schwarz 2 1. Introduction Much has been written and discussed on a case of common irritations regarding a news picture depicting a scene from South Beirut in the context of the Israel-Hezbollah war striking over particular areas of Lebanon in 2006. Much has been said about