Pre-Colonial History of the Wangunk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(King Philip's War), 1675-1676 Dissertation Presented in Partial

Connecticut Unscathed: Victory in The Great Narragansett War (King Philip’s War), 1675-1676 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Major Jason W. Warren, M.A. Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: John F. Guilmartin Jr., Advisor Alan Gallay, Kristen Gremillion Peter Mansoor, Geoffrey Parker Copyright by Jason W. Warren 2011 Abstract King Philip’s War (1675-1676) was one of the bloodiest per capita in American history. Although hostile native groups damaged much of New England, Connecticut emerged unscathed from the conflict. Connecticut’s role has been obscured by historians’ focus on the disasters in the other colonies as well as a misplaced emphasis on “King Philip,” a chief sachem of the Wampanoag groups. Although Philip formed the initial hostile coalition and served as an important leader, he was later overshadowed by other sachems of stronger native groups such as the Narragansetts. Viewing the conflict through the lens of a ‘Great Narragansett War’ brings Connecticut’s role more clearly into focus, and indeed enables a more accurate narrative for the conflict. Connecticut achieved success where other colonies failed by establishing a policy of moderation towards the native groups living within its borders. This relationship set the stage for successful military operations. Local native groups, whether allied or neutral did not assist hostile Indians, denying them the critical intelligence necessary to coordinate attacks on Connecticut towns. The English colonists convinced allied Mohegan, Pequot, and Western Niantic warriors to support their military operations, giving Connecticut forces a decisive advantage in the field. -

Native Milwaukee Bryan C

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette History Faculty Research and Publications History, Department of 1-1-2016 Native Milwaukee Bryan C. Rindfleisch Marquette University, [email protected] Published version. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Publisher link. © 2016 Encyclopedia of Milwaukee. Used with permission. Search Site... Menu Log In or Register Native Milwaukee Click the image to learn more. The Indigenous Peoples of North America have always claimed Milwaukee as their own. Known as the “gathering place by the waters,” the “good earth” (or good land), or simply the “gathering place,” Indigenous groups such as the Potawatomi, Ojibwe, Odawa (Ottawa), Fox, Ho-Chunk, Menominee, Sauk, and Oneida have all called Milwaukee their home at some point in the last three centuries. This does not include the many other Native populations in Milwaukee today, ranging from Wisconsin groups like the Stockbridge-Munsee and Brothertown Nation, to outer-Wisconsin peoples like the Lakota and Dakota (Sioux), First Nations, Creek, Chickasaw, Sac, Meskwaki, Miami, Kickapoo, Micmac, and Cherokee, among others. According to the 2010 census, over 7,000 people in Milwaukee County identified as American Indian or Alaska Native, making Milwaukee the largest concentration of Native Peoples statewide. Milwaukee, then, is—and has always been—a Native place, home to a diverse number of Indigenous Americans. Native Milwaukee’s Creation Story is thousands of years old, when the Mound Builders civilizations, also known as the Adena, Hopewell, Woodlands, and Mississippian cultures, flourished in the Great Lakes, Ohio River Valley, and Mississippi River Valley between 500 BCE to 1200 CE (some scholars even suggest 1500 CE). It is estimated the Mound-Builder civilization spread to southeastern Wisconsin in the Early Woodland Era, sometime between 800 and 500 BCE, and flourished during the Middle Woodland Era (100 BCE to 500 CE). -

A Brief History of Native Americans in Essex, Connecticut

A Brief History of Native Americans in Essex, Connecticut by Verena Harfst, Essex Table of Contents Special Thanks and an Appeal to the Community 3 - 4 Introduction 5 The Paleo-Indian Period 6 - 7 The Archaic Period 7 - 10 The Woodland Period 11 – 12 Algonquians Settle Connecticut 12 - 14 Thousands of Years of Native American Presence in Essex 15 - 19 Native American Life in the Essex Area Shortly Before European Arrival 19 - 23 Arrival of the Dutch and the English 23 - 25 Conflict and Defeat 25 - 28 The Fate of the Nihantic 28 - 31 Postscript 31 Footnotes 31 - 37 2 Special Thanks and an Appeal to the Community This article contributes to an ongoing project of the Essex Historical Society (EHS) and the Essex Land Trust to celebrate the history of the Falls River in south central Connecticut. This modest but lovely watercourse connects the three communities comprising the Town of Essex, wending its way through Ivoryton, Centerbrook and Essex Village, where it flows into North Cove and ultimately the main channel of the Connecticut River a few miles above Long Island Sound. Coined “Follow the Falls”, the project is being conducted largely by volunteers devoted to their beautiful town and committed to helping the Essex Historical Society and the Essex Land Trust achieve their missions. This article by a local resident focuses on the history of the Indigenous People of Essex. The article is based on interviews the author conducted with a number of archaeologists and historians as well as reviews of written materials readily accessible on the history of Native Americans in New England. -

Identifying the Ojibwa

Identifying the Ojibwa THERESA SCHENCK Rutgers University The Ojibwa are generally recognized as one of the largest groups of native peoples of North America. It has long been argued, however, just who should be considered Ojibwa, and how far they extended at the time of first contact (Bishop and Smith 1975; Greenberg and Morrison 1982). Most studies of the Ojibwa have proceded from two premises: first, that all groups now known as Ojibwa were originally Ojibwa, and second, that native cultures were essentially static. Thus it is assumed that those who are considered Ojibwa today were always Ojibwa, but that they were misnamed in early French records. I have found, on the contrary, that the name Ojibwa has been extended far beyond the original boundaries of the 17th-century people. Using historical documents and records of Ojibwa tradition, I propose to identify the Ojibwa in the 17th century, to trace them throughout the early period after contact, and to explain how so many people who were not originally Ojibwa came to be called Ojibwa. The Ojibwa, located in the summer at the rapids or falls between Lake Superior and Lake Huron, were mentioned for the first time in Du Peron's letter of 1639 as the nation of the Sault (Thwaites 1959(15):155). The following year Le Jeune referred to them as Saulteurs, the people who reside at the rapids, and it is as such that they were known throughout much of the French period (Thwaites 1959(18):231). Before identifying these Saulteurs I wish to suggest several principles of naming Amerindian groups. -

The Algonquian Totem and Totemism: a Distortion of the Semantic Field

The Algonquian Totem and Totemism: A Distortion of the Semantic Field THERESA M. SCHENCK Rutgers University In 1952 A. R. Radcliffe-Brown asked whether "totemism as a technical term has not outlived its usefulness" (1965:117). The question is rather whether it should ever have been used at all. After more than a century of use and abuse, it is time to re-examine the earliest known use of the word, and to trace the development of the idea of totemism through the historic period. It can be shown that the meaning became distorted in the 19th century, and that this distortion has in rum influenced contemporary usage. The earliest recorded form of the Algonquin word totem is 8ten, translated as 'village' by an unknown Jesuit missionary in his Dictionnaire algonquin (Anonymous 1661:48). Since it was usually spoken as nind otem 'my village', the word was soon heard as totem, or dodem. For the Algonquin, however, the word did not connote a permanent group of houses as the word village did for the French. Rather the 8ten was a group of people tied together by kinship, who moved together seasonally. The village was the people, not the place. In general, all the people of the village were related (except, of course, the wives, who were necessarily of different totems), hence "my village" was "my family". In fact, in his Algonquin dictionary, Jean-Andre Cuoq gave the following explanation for ote- 'village' from the Abbe Thavenet, an early 19th-century missionary at Lac-des-Deux-Montagnes, Quebec: "it signifies family, all the persons who live in the same lodge under the same chief (Cuoq 1886:312). -

Proposed Finding for Federal Acknowledgment of the Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians, Peshawbestown, Michigan Pursuant to 25 CFR 54

Tribal Government Services OCT 3 1979 MEMORP.NDUM To: Assistant Secretary From: Acting Deputy Commissioner Subject: Recommendation and summary of evidence for proposed finding for Federal acknowledgment of the Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians, Peshawbestown, Michigan pursuant to 25 CFR 54. I. RECOMMENDATION: We recommend the Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians be acknowledged as an Indian Tribe with a government-to-government relationship with the United States and entitled to the same privileges and immunities available to other Federally recognized tribes by virtue of their status as Indian tribes. II. GENERAL CONCLUSIONS: The Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians is the modern successor of several bands of Ottawas and Chippewas which have a documented continuous existence in the Grand Traverse Bay area of Michigan since as early as 1675. Evidence indicates these bands, and the subsequent combined band, have existed autonomously since first contact, with a series of leaders who representl~d the band in its dealings with outside organizations, and who both responded to and influenced the band in matters of importance. The membership is unques·:jonably Indian, of Ottawa and Chippewa descent. No evidence was found tha t the members of the band are members of any other Indian tribes, or that the band or its members have been terminated or forbidden the Federal relationship by an Act of Congress. III. BRIEF HISTORY: The Ottawa and Chippewa are two closely related Algonquian peoples who originally occupied an area bordering on Lakes Superior, Michigan, and Huron. They were initially encountered by French explorers in the mid-1600's. -

History of Rocky Hill: 1650 - 2018 Robert Campbell Herron October 2017

History of Rocky Hill: 1650 - 2018 Robert Campbell Herron October 2017 Bring Us Your History ........................................................................................................ 4 Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................. 4 Origins: 250,000,000 BCE to 1730 CE .............................................................................. 4 Dinosaurs ........................................................................................................................ 4 Pre-European History...................................................................................................... 5 The Europeans Arrive ..................................................................................................... 5 The Settlement of the Town ............................................................................................ 6 Maritime Rocky Hill ........................................................................................................... 6 The Ferry ......................................................................................................................... 7 The River and Seafaring ................................................................................................. 7 Rocky Hill and Slavery ..................................................................................................... 10 Slaves in Rocky Hill .................................................................................................... -

Facts for Kids: Algonquian People (

Facts for Kids: Algonquian People (http://www.native-languages.org/languages.htm) How do you pronounce "Algonquian?" What does it mean? It's pronounced "al-GON-kee-un." It doesn't actually mean anything. Anthropologists invented this term to refer to tribes who spoke a related group of languages. What is the right way to spell "Algonquian"? It can be spelled either "Algonquian" or "Algonkian." Either spelling is correct. Are the Algonquians extinct? Certainly not! There are more than half a million Native American people today belonging to Algonquian tribes. But you may not be able to find online information about modern Algonquian people if you do a search for “Algonquian” -- because they rarely call themselves by this name. Try looking them up by their real tribal names. There are a few extinct Algonquian tribes, including the Beothuk and Wappinger tribes, but most Algonquian tribes still survive today. Which tribes are Algonquian? The many Algonquian tribes include the Abenakis, Algonquins, Arapahos, Attikameks, Blackfeet, Cheyennes, Crees, Gros Ventre, Illini, Kickapoo, Lenni Lenape/Delawares, Lumbees (Croatan Indians), Mahicans (including Mohicans, Stockbridge Indians, and Wappingers), Maliseets, Menominees, Sac and Fox, Miamis, Métis/Michif, Mi'kmaq/Micmacs, Mohegans (including Pequots, Montauks, Niantics, and Shinnecocks), Montagnais/Innu, Munsees, Nanticokes, Narragansetts, Naskapis, Ojibways/Chippewas, Ottawas, Passamaquoddy, Penobscots, Potawatomis, Powhatans, Shawnees, Wampanoags (including the Massachusett, Natick, and Mashpee), Wiyot, and Yurok. Where do the Algonquian Indians live? Algonquian people live throughout the United States, from California to Maine, and throughout southern Canada, from Alberta to Labrador. On the right is a map showing the original homelands of various Algonquian peoples. -

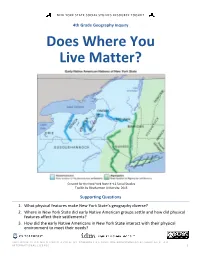

Does Where You Live Matter?

NEW YORK STATE SOCIAL STUDIES RESOURCE TOOLKIT 4th Grade Geography Inquiry Does Where You Live Matter? Created for the New York State K–12 Social Studies Toolkit by Binghamton University, 2015 Supporting Questions 1. What physical features make New York State’s geography diverse? 2. Where in New York State did early Native American groups settle and how did physical features affect their settlements? 3. How did the early Native Americans in New York State interact with their physical environment to meet their needs? THIS WORK IS LICENSED UNDER A CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION- NONCOMMERCIAL- SHAREALIKE 4.0 INTERNATIONAL LICENSE. 1 NEW YORK STATE SOCIAL STUDIES RESOURCE TOOLKIT 4th Grade Geography Inquiry How Does Where You Live Matter? 4.1 GEOGRAPHY OF NEW YORK STATE: New York State has a diverse geography. Various maps can be used to represent and examine the geography of New York State. New York State Social Studies 4.2 NATIVE AMERICAN GROUPS AND THE ENVIRONMENT: Native American groups, chiefly the Iroquois Framework Key (Haudenosaunee) and Algonquian-speaking groups, inhabited the region that became New York State. Ideas & PraCtices Native American Indians interacted with the environment and developed unique cultures. Gathering, Using, and Interpreting EvidenCe Comparison and Contextualization Economics and Economic Systems GeographiC Reasoning Staging the Brainstorm the relationship between humans and the physical environment through the concepts of Question opportunities and constraints. Supporting Question 1 Supporting Question 2 -

The Pequot War

The Pequot War The Native Americans and the English settlers were on a collision course. In the early 1600s, more than 8,000 Pequots lived in southeastern Connecticut. They traded with the Dutch. The Pequots controlled the fur and wampum trade. Their strong leaders and communities controlled tribes across southern New England. It was a peaceful time between 1611 and 1633. But all was not well. Contact with Europeans during this period brought a deadly disease. Smallpox killed half of the Pequots by 1635. The English arrived in 1633. The English wanted to trade with the Native Americans, too. The Dutch and Pequots tried to stay in control of all trade. This led to misunderstanding, conflict, and violence. In the summer of 1634, a Virginia trader and his crew sailed up the Connecticut River. They took captive several Pequots as guides. It’s not clear what happened or why, but the Virginia trader and crew were killed. The English wanted the Pequots punished for the crime. They attacked and burned a Pequot village on the Thames River and killed several Pequots. The Pequots fought back. All winter and spring of 1637 the Pequot attacked anyone who left the English fort at Saybrook Point. They destroyed food and supplies. They stopped any boats from sailing up the river to Windsor, Wethersfield, and Hartford. More than 20 English soldiers were killed. © Connecticut Explored Inc. Massachusetts sent 20 soldiers to help the English soldiers at Saybrook Point. Then the Pequots attacked Wethersfield. They killed nine men and two women and captured two girls. -

Algonquian Mastery of the Great Lakes

Inland Sea Navigators: Algonquian Mastery of the Great Lakes VICTOR P. LYTWYN Acton, Ontario Few if any European newcomers failed to be impressed with the water- craft used by Aboriginal people in North America. They were particularly enamoured with the birch bark canoes used by Algonquian-speaking peo ples in the Great Lakes region. Early writers agreed that these canoes were well suited to travel from the white water of rushing rivers to the vast expanse of the Great Lakes. In 1724, for example, Joseph Francois Lafitau described the construction of birch-bark canoes as "masterpieces of native art" (1977:124). He continued: "Nothing is prettier and more admirable than these fragile craft in which people can carry heavy loads and go everywhere very rapidly." Edwin Tappan Adney and Howard Chapelle's seminal study of the canoe in North America commented (1964:3), "Indian bark canoes were most efficient water craft for use in forest travel" and "open water in lakes." Algonquian-speaking peoples in the Great Lakes region were espe cially noted for their skill in building and navigating birch bark canoes. The Jesuit missionary Francesco Gioseppe Bressani noted that Aboriginal people in the region around Lake Huron were expert navigators. He wrote in 1654 (JR 38:247): The somewhat long and dangerous navigation which they conduct, on rivers and enormous lakes, with very distant nations for the beaver trade, is effected within little boats of bark, no thicker than a testone - holding at the most 8 or 10 persons, but commonly not more than three or four; they manoeuver these dexterously, and almost without danger. -

Bison, Slavery, and the Rise and Fall of the Grand Village of the Kaskaskia

The Power of the Ecotone: Bison, Slavery, and the Rise and Fall of the Grand Village of the Kaskaskia Robert Michael Morrissey Downloaded from Among the largest population centers in North America toward the end of the seventeenth century was the Grand Village of the Kaskaskia, which, combined with surrounding set- tlements, enveloped as many as twenty thousand people for approximately two decades. http://jah.oxfordjournals.org/ Located at the top of the Illinois River valley, the village is not normally considered a significant part of American history, so it has remained relatively unknown. In many ac- counts, the location is discussed merely as a refugee center to which desperate, beleaguered Algonquians fled ahead of a series of mid-seventeenth-century Iroquois conquests that were part of the violence known as the Beaver Wars. Reeling from violence and constrained by necessity, the Illinois speakers who predominated in the place belonged to a “fragile, dis- ordered world,” “made of fragments” and dependent on French support. The size of the settlement did not reflect a particular level of native power but was simply proportional to at Indiana University Libraries on July 12, 2016 the devastation, suffering, and urgency felt by the people of the pays d’en haut (the Great Lakes area)—and particularly by the Illinois—at the start of the colonial period.1 Robert Michael Morrissey is an assistant professor of history at the University of Illinois. He wishes to thank Aaron Sachs, Gerry Cadava, John White, Jake Lundberg, Fred Hoxie, Antoinette Burton, Kathleen DuVal, Ben Irwin, John Hoffman, the University of Illinois Department of History, members of the History Workshop at the Univer- sity of Illinois; Edward T.