Logical Form

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sentence Types and Functions

San José State University Writing Center www.sjsu.edu/writingcenter Written by Sarah Andersen Sentence Types and Functions Choosing what types of sentences to use in an essay can be challenging for several reasons. The writer must consider the following questions: Are my ideas simple or complex? Do my ideas require shorter statements or longer explanations? How do I express my ideas clearly? This handout discusses the basic components of a sentence, the different types of sentences, and various functions of each type of sentence. What Is a Sentence? A sentence is a complete set of words that conveys meaning. A sentence can communicate o a statement (I am studying.) o a command (Go away.) o an exclamation (I’m so excited!) o a question (What time is it?) A sentence is composed of one or more clauses. A clause contains a subject and verb. Independent and Dependent Clauses There are two types of clauses: independent clauses and dependent clauses. A sentence contains at least one independent clause and may contain one or more dependent clauses. An independent clause (or main clause) o is a complete thought. o can stand by itself. A dependent clause (or subordinate clause) o is an incomplete thought. o cannot stand by itself. You can spot a dependent clause by identifying the subordinating conjunction. A subordinating conjunction creates a dependent clause that relies on the rest of the sentence for meaning. The following list provides some examples of subordinating conjunctions. after although as because before even though if since though when while until unless whereas Independent and Dependent Clauses Independent clause: When I go to the movies, I usually buy popcorn. -

Questions Under Discussion: from Sentence to Discourse∗

Questions under Discussion: From sentence to discourse∗ Anton Benz Katja Jasinskaja July 14, 2016 Abstract Questions under discussion (QUD) is an analytic tool that has recently become more and more popular among linguists and language philosophers as a way to characterize how a sentence fits in its context. The idea is that each sentence in discourse addresses a (of- ten implicit) QUD either by answering it, or by bringing up another question that can help answering that QUD. The linguistic form and the interpretation of a sentence, in turn, may depend on the QUD it addresses. The first proponents of the QUD approach (von Stut- terheim & Klein, 1989; van Kuppevelt, 1995) thought of it as a general approach to the analysis of discourse structure where structural relations between sentences in a coherent discourse are understood in terms of relations between questions they address. However, the idea did not find broad application in discourse structure analysis, where theories aiming at logical discourse representations are predominantly based on the notion of coherence re- lations (Mann & Thompson, 1988; Hobbs, 1985; Asher & Lascarides, 2003). The problem of finding overt markers for QUDs means that they are also difficult to utilize for quanti- tative measures of discourse coherence (McNamara et al., 2010). At the same time QUD proved useful in the analysis of a wide range of linguistic phenomena including accentua- tion, discourse particles, presuppositions and implicatures. The goal of this special issue is to bring together cutting-edge research that demonstrates the success of QUD in linguistics and the need for the development of a comprehensive model of discourse coherence that incorporates the notion of QUD as its integral part. -

The Meaning of Language

01:615:201 Introduction to Linguistic Theory Adam Szczegielniak The Meaning of Language Copyright in part: Cengage learning The Meaning of Language • When you know a language you know: • When a word is meaningful or meaningless, when a word has two meanings, when two words have the same meaning, and what words refer to (in the real world or imagination) • When a sentence is meaningful or meaningless, when a sentence has two meanings, when two sentences have the same meaning, and whether a sentence is true or false (the truth conditions of the sentence) • Semantics is the study of the meaning of morphemes, words, phrases, and sentences – Lexical semantics: the meaning of words and the relationships among words – Phrasal or sentential semantics: the meaning of syntactic units larger than one word Truth • Compositional semantics: formulating semantic rules that build the meaning of a sentence based on the meaning of the words and how they combine – Also known as truth-conditional semantics because the speaker’ s knowledge of truth conditions is central Truth • If you know the meaning of a sentence, you can determine under what conditions it is true or false – You don’ t need to know whether or not a sentence is true or false to understand it, so knowing the meaning of a sentence means knowing under what circumstances it would be true or false • Most sentences are true or false depending on the situation – But some sentences are always true (tautologies) – And some are always false (contradictions) Entailment and Related Notions • Entailment: one sentence entails another if whenever the first sentence is true the second one must be true also Jack swims beautifully. -

VP Ellipsis Without Parallel Binding∗

Proceedings of SALT 24: 000–000, 2014 The sticky reading: VP ellipsis without parallel binding∗ Patrick D. Elliott Andreea C. Nicolae University College London ZAS Berlin Yasutada Sudo University College London Abstract VP Ellipsis (VPE) whose antecedent VP contains a pronoun famously gives rise to an ambiguity between strict and sloppy readings. Since Sag’s (1976) seminal work, it is generally assumed that the strict reading involves free pronouns in both the elided VP and its antecedent, whereas the sloppy reading involves bound pronouns. The majority of current approaches to VPE are tailored to derive this parallel binding requirement, ruling out mixed readings where one of the VPs involves a bound pronoun and the other a free pronoun in parallel positions. Contrary to this assumption, it is observed that there are cases of VPE where the antecedent VP contains a bound pronoun but the elided VP contains a free E-type pronoun anchored to the quantifier, in violation of parallel binding. We dub this the ‘sticky reading’ of VPE. To account for it, we propose a new identity condition on VPE which is less stringent than is standardly assumed. We formalize this using an extension of Roberts’s (2012) Question under Discussion (QuD) theory of information structure. Keywords: VP ellipsis, strict/sloppy identity, pronominal binding, focus, Question under Discussion 1 Introduction It has been famously observed by Sag(1976) that pronouns give rise to an ambiguity in a VP Ellipsis (VPE) context. An example such as (1) is claimed to be ambiguous between so-called strict and sloppy readings. (1) Jonny totaled his car, and Kevin did h...i too. -

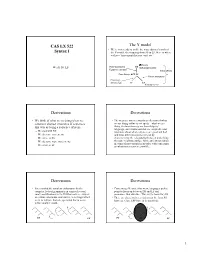

CAS LX 522 Syntax I the Y Model

CAS LX 522 The Y model • We’re now ready to tackle the most abstract branch of Syntax I the Y-model, the mapping from SS to LF. Here is where we have “movement that you can’t see”. θ Theory Week 10. LF Overt movement, DS Subcategorization Expletive insertion X-bar theory Case theory, EPP SS Covert movement Phonology/ Morphology PF LF Binding theory Derivations Derivations • We think of what we’re doing when we • The steps are not necessarily a reflection of what construct abstract structures of sentences we are doing online as we speak—what we are this way as being a sequence of steps. doing is characterizing our knowledge of language, and it turns out that we can predict our – We start with DS intuitions about what sentences are good and bad – We do some movements and what different sentences mean by – We arrive at SS characterizing the relationship between underlying – We do some more movements thematic relations, surface form, and interpretation in terms of movements in an order with constraints – We arrive at LF on what movements are possible. Derivations Derivations • It seems that the simplest explanation for the • Concerning SS, under this view, languages pick a complex facts of grammar is in terms of several point to focus on between DS and LF and small modifications to the DS that each are subject pronounce that structure. This is (the basis for) SS. to certain constraints, sometimes even things which • There are also certain restrictions on the form SS seem to indicate that one operation has to occur has (e.g., Case, EPP have to be satisfied). -

Minimal Pronouns, Logophoricity and Long-Distance Reflexivisation in Avar

Minimal pronouns, logophoricity and long-distance reflexivisation in Avar* Pavel Rudnev Revised version; 28th January 2015 Abstract This paper discusses two morphologically related anaphoric pronouns inAvar (Avar-Andic, Nakh-Daghestanian) and proposes that one of them should be treated as a minimal pronoun that receives its interpretation from a λ-operator situated on a phasal head whereas the other is a logophoric pro- noun denoting the author of the reported event. Keywords: reflexivity, logophoricity, binding, syntax, semantics, Avar 1 Introduction This paper has two aims. One is to make a descriptive contribution to the crosslin- guistic study of long-distance anaphoric dependencies by presenting an overview of the properties of two kinds of reflexive pronoun in Avar, a Nakh-Daghestanian language spoken natively by about 700,000 people mostly living in the North East Caucasian republic of Daghestan in the Russian Federation. The other goal is to highlight the relevance of the newly introduced data from an understudied lan- guage to the theoretical debate on the nature of reflexivity, long-distance anaphora and logophoricity. The issue at the heart of this paper is the unusual character of theanaphoric system in Avar, which is tripartite. (1) is intended as just a preview with more *The present material was presented at the Utrecht workshop The World of Reflexives in August 2011. I am grateful to the workshop’s audience and participants for their questions and comments. I am indebted to Eric Reuland and an anonymous reviewer for providing valuable feedback on the first draft, as well as to Yakov Testelets for numerous discussions of anaphora-related issues inAvar spanning several years. -

8. Binding Theory

THE COMPLICATED AND MURKY WORLD OF BINDING THEORY We’re about to get sucked into a black hole … 11-13 March Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. Ussery 2 OUR ROADMAP •Overview of Basic Binding Theory •Binding and Infinitives •Some cross-linguistic comparisons: Icelandic, Ewe, and Logophors •Picture NPs •Binding and Movement: The Nixon Sentences 3 SOME TERMINOLOGY • R-expression: A DP that gets its meaning by referring to an entity in the world. • Anaphor: A DP that obligatorily gets its meaning from another DP in the sentence. 1. Heidi bopped herself on the head with a zucchini. [Carnie 2013: Ch. 5, EX 3] • Reflexives: Myself, Yourself, Herself, Himself, Itself, Ourselves, Yourselves, Themselves • Reciprocals: Each Other, One Another • Pronoun: A DP that may get its meaning from another DP in the sentence or contextually, from the discourse. 2. Art said that he played basketball. [EX5] • “He” could be Art or someone else. • I/Me, You/You, She/Her, He/Him, It/It, We/Us, You/You, They/Them • Nominative/Accusative Pronoun Pairs in English • Antecedent: A DP that gives its meaning to another DP. • This is familiar from control; PRO needs an antecedent. Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. Ussery 4 OBSERVATION 1: NO NOMINATIVE FORMS OF ANAPHORS • This makes sense, since anaphors cannot be subjects of finite clauses. 1. * Sheselfi / Herselfi bopped Heidii on the head with a zucchini. • Anaphors can be the subjects of ECM clauses. 2. Heidi believes herself to be an excellent cook, even though she always bops herself on the head with zucchini. SOME DESCRIPTIVE OBSERVATIONS Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. -

Pronouns, Logical Variables, and Logophoricity in Abe Author(S): Hilda Koopman and Dominique Sportiche Source: Linguistic Inquiry, Vol

MIT Press Pronouns, Logical Variables, and Logophoricity in Abe Author(s): Hilda Koopman and Dominique Sportiche Source: Linguistic Inquiry, Vol. 20, No. 4 (Autumn, 1989), pp. 555-588 Published by: MIT Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4178645 Accessed: 22-10-2015 18:32 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. MIT Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Linguistic Inquiry. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.97.27.20 on Thu, 22 Oct 2015 18:32:27 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Hilda Koopman Pronouns, Logical Variables, Dominique Sportiche and Logophoricity in Abe 1. Introduction 1.1. Preliminaries In this article we describe and analyze the propertiesof the pronominalsystem of Abe, a Kwa language spoken in the Ivory Coast, which we view as part of the study of pronominalentities (that is, of possible pronominaltypes) and of pronominalsystems (that is, of the cooccurrence restrictionson pronominaltypes in a particulargrammar). Abe has two series of thirdperson pronouns. One type of pronoun(0-pronoun) has basically the same propertiesas pronouns in languageslike English. The other type of pronoun(n-pronoun) very roughly corresponds to what has been called the referential use of pronounsin English(see Evans (1980)).It is also used as what is called a logophoric pronoun-that is, a particularpronoun that occurs in special embedded contexts (the logophoric contexts) to indicate reference to "the person whose speech, thought or perceptions are reported" (Clements (1975)). -

Against Logical Form

Against logical form Zolta´n Gendler Szabo´ Conceptions of logical form are stranded between extremes. On one side are those who think the logical form of a sentence has little to do with logic; on the other, those who think it has little to do with the sentence. Most of us would prefer a conception that strikes a balance: logical form that is an objective feature of a sentence and captures its logical character. I will argue that we cannot get what we want. What are these extreme conceptions? In linguistics, logical form is typically con- ceived of as a level of representation where ambiguities have been resolved. According to one highly developed view—Chomsky’s minimalism—logical form is one of the outputs of the derivation of a sentence. The derivation begins with a set of lexical items and after initial mergers it splits into two: on one branch phonological operations are applied without semantic effect; on the other are semantic operations without phono- logical realization. At the end of the first branch is phonological form, the input to the articulatory–perceptual system; and at the end of the second is logical form, the input to the conceptual–intentional system.1 Thus conceived, logical form encompasses all and only information required for interpretation. But semantic and logical information do not fully overlap. The connectives “and” and “but” are surely not synonyms, but the difference in meaning probably does not concern logic. On the other hand, it is of utmost logical importance whether “finitely many” or “equinumerous” are logical constants even though it is hard to see how this information could be essential for their interpretation. -

Coreference Resolution for Spoken French Loïc Grobol

Coreference resolution for spoken French Loïc Grobol To cite this version: Loïc Grobol. Coreference resolution for spoken French. Computation and Language [cs.CL]. Université Sorbonne Nouvelle - Paris 3, 2020. English. tel-02928209v2 HAL Id: tel-02928209 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-02928209v2 Submitted on 9 Mar 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution| 4.0 International License École Doctorale 622 — Sciences du langage Lattice, Inria Thèse de doctorat en sciences du langage de l’Université Sorbonne Nouvelle Coreference resolution for spoken French présentée et soutenue publiquement par Loïc Grobol le 15 juillet 2020 Sous la direction d’Isabelle Tellier† et de Frédéric Landragin Et co-encadrée par Éric Villemonte de la Clergerie et Marco Dinarelli Jury : Massimo Poesio, Professor (Queen Mary University), Rapporteur, Sophie Rosset, Directrice de recherche (LIMSI), Rapportrice, Béatrice Daille, Professeur (Université de Nantes), Examinatrice, Pascal Amsili, Professeur (Université Sorbonne Nouvelle), Examinateur, Frédéric Landragin, Directeur de recherche (Lattice), Directeur, Éric Villemonte de la Clergerie, Chargé de recherche (Inria), Co-encadrant, Marco Dinarelli, Chargé de recherche (LIG), Co-encadrant. Reconnaissance automatique de chaînes de coréférences en français parlé Résumé Une chaîne de coréférences est l’ensemble des expressions linguistiques — ou mentions — qui font référence à une même entité ou un même objet du discours. -

A Syntactic Analysis of Rhetorical Questions

A Syntactic Analysis of Rhetorical Questions Asier Alcázar 1. Introduction* A rhetorical question (RQ: 1b) is viewed as a pragmatic reading of a genuine question (GQ: 1a). (1) a. Who helped John? [Mary, Peter, his mother, his brother, a neighbor, the police…] b. Who helped John? [Speaker follows up: “Well, me, of course…who else?”] Rohde (2006) and Caponigro & Sprouse (2007) view RQs as interrogatives biased in their answer set (1a = unbiased interrogative; 1b = biased interrogative). In unbiased interrogatives, the probability distribution of the answers is even.1 The answer in RQs is biased because it belongs in the Common Ground (CG, Stalnaker 1978), a set of mutual or common beliefs shared by speaker and addressee. The difference between RQs and GQs is thus pragmatic. Let us refer to these approaches as Option A. Sadock (1971, 1974) and Han (2002), by contrast, analyze RQs as no longer interrogative, but rather as assertions of opposite polarity (2a = 2b). Accordingly, RQs are not defined in terms of the properties of their answer set. The CG is not invoked. Let us call these analyses Option B. (2) a. Speaker says: “I did not lie.” b. Speaker says: “Did I lie?” [Speaker follows up: “No! I didn’t!”] For Han (2002: 222) RQs point to a pragmatic interface: “The representation at this level is not LF, which is the output of syntax, but more abstract than that. It is the output of further post-LF derivation via interaction with at least a sub part of the interpretational component, namely pragmatics.” RQs are not seen as syntactic objects, but rather as a post-syntactic interface phenomenon. -

Mind the GAP: a Balanced Corpus of Gendered Ambiguous Pronouns

Mind the GAP: A Balanced Corpus of Gendered Ambiguous Pronouns Kellie Webster and Marta Recasens and Vera Axelrod and Jason Baldridge Google AI Language fwebsterk|recasens|vaxelrod|[email protected] Abstract (1) In May, Fujisawa joined Mari Motohashi’s rink as the team’s skip, moving back from Karuizawa to Ki- Coreference resolution is an important task tami where she had spent her junior days. for natural language understanding, and the resolution of ambiguous pronouns a long- With this scope, we make three key contributions: standing challenge. Nonetheless, existing • We design an extensible, language- corpora do not capture ambiguous pronouns in sufficient volume or diversity to accu- independent mechanism for extracting rately indicate the practical utility of mod- challenging ambiguous pronouns from text. els. Furthermore, we find gender bias in • We build and release GAP, a human-labeled existing corpora and systems favoring mas- corpus of 8,908 ambiguous pronoun-name culine entities. To address this, we present pairs derived from Wikipedia.2 This dataset and release GAP, a gender-balanced labeled targets the challenges of resolving naturally- corpus of 8,908 ambiguous pronoun-name occurring ambiguous pronouns and rewards pairs sampled to provide diverse coverage systems which are gender-fair. of challenges posed by real-world text. We explore a range of baselines which demon- • We run four state-of-the-art coreference re- strate the complexity of the challenge, the solvers and several competitive simple base- best achieving just 66.9% F1. We show lines on GAP to understand limitations in that syntactic structure and continuous neu- current modeling, including gender bias.