Balaam Is Laban

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Expositor

THE EXPOSITOR. BALAAM: AN EXPOSITION AND STUDY. III. The Conclusion. WE have now studied all the Scriptures which relate to Balaam, and if our study has added but few new features to his character, it has served, I hope, to bring out his features more clearly, to cast higher lights and deeper shadows upon them, and to define and enlarge our conceptions both of the good and of the evil qualities of the man. The problem of his character-how a good man could be so. bad and a great man so base-has not yet been solved ; we are as far per haps from its solution as ever : but something-much has been gained if only we have the terms of that problem more distinctly and fully before our minds. To reach the solution of it, in so far as we can reach it, we must fall back on the second method of inquiry which, at the outset, I proposed to employ. We must apply the comparative method to the history and character of Balaam ; we must place him beside other prophets as faulty and sinful as himself, and in whom the elements were as strangely mixed as they were in him : we must endeavour to classify him, and to read the problem of his life in the light of that of men of his own order and type. Yet that is by no means easy to do without putting him to a grave disadvantage. For the only prophets with whom We can compare him are the Hebrew prophets ; and ·Balaam JULY, 1883. -

Japheth and Balaam

Redemption 304: Further Study on Japheth and Balaam biblestudying.net Brian K. McPherson and Scott McPherson Copyright 2012 Melchizedek (Shem), Japheth, and Balaam Summary of Relevant Information from Genesis Regarding Melchizedek and Abraham This exploratory paper assumes the conclusions of section three of our “Priesthood and the Kinsman Redeemer” study which identifies Melchizedek as Noah’s son Shem. Melchizedek was priest of Jerusalem (Salem) and possibly of the region in general. Shem was granted dominion over all the Canaanites by Noah. Genesis 9:22 And Ham, the father of Canaan, saw the nakedness of his father, and told his two brethren without. 23 And Shem and Japheth took a garment, and laid it upon both their shoulders, and went backward, and covered the nakedness of their father; and their faces were backward, and they saw not their father’s nakedness. 24 And Noah awoke from his wine, and knew what his younger son had done unto him. 25 And he said, Cursed be Canaan; a servant of servants shall he be unto his brethren. 26 And he said, Blessed be the LORD God of Shem; and Canaan shall be his servant. Melchizedek is clearly presented as a king. And Abraham clearly pays tithes or tribute to this king after a victory in battle. Genesis 14:18 And Melchizedek king of Salem brought forth bread and wine: and he was the priest of the most high God. 19 And he blessed him, and said, Blessed be Abram of the most high God, possessor of heaven and earth: 20 And blessed be the most high God, which hath delivered thine enemies into thy hand. -

Prophets, Posters and Poetry Joshua Fallik

Prophets, Posters and Poetry Joshua Fallik Subject Area: Torah (Prophets) Multi-unit lesson plan Target age: 5th – 8th grades, 9th – 12th grades Objectives: • To acquaint students with prophets they may be unfamiliar with. • To familiarize the students with the social and moral message of selected prophets by engaging their analytical minds and visual senses. • To have students reflect in various media on the message of each of these prophets. • To introduce the students to contemporary examples of individuals who seem to live in the spirit of the prophets and their teachings. Materials: Descriptions of various forms of poetry including haiku, cinquain, acrostic, and free verse. Poster board, paper, markers, crayons, pencils, erasers. Quotations from the specific prophet being studied. Students may choose to use any of the materials available to create their sketches and posters. Class 1 through 3: Introduction to the prophets. The prophet Jonah. Teacher briefly talks about the role of the prophets. (See What is a Prophet, below) Teacher asks the students to relate the story of Jonah. Teacher briefly discusses the historical and social background of the prophet. Teacher asks if they can think of any fictional characters named Jonah. Why is the son in Sleepless in Seattle named Jonah? Teacher briefly talks about different forms of poetry. (see Poetry Forms, below) Students are asked to write a poem (any format) about the prophet Jonah. Students then draw a sketch that illustrates the Jonah story. Students create a poster based on the sketch and incorporating the poem they have written. Classes 4 through 8: The prophet Micah. -

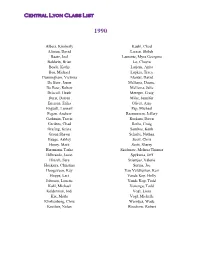

Central Lyon Class List

Central Lyon Class List 1990 Albers, Kimberly Kuehl, Chad Altman, David Larsen, Shiloh Baatz, Joel Laurente, Myra Georgina Baldwin, Brian Lo, Chayra Boyle, Kathy Lutjens, Anita Bus, Michael Lupkes, Tracy Cunningham, Victoria Mantal, David De Beor, Jason Mellema, Duane, De Boer, Robert Mellema, Julie Driscoll, Heath Metzger, Craig Durst, Darren Milar, Jennifer Enersen, Erika Oliver, Amy Enguall, Lennart Pap, Michael Fegan, Andrew Rasmussem, Jeffery Gathman, Travis Roskam, Dawn Gerdees, Chad Roths, Craig Grafing, Krista Sambos, Keith Groen Shawn Schulte, Nathan Hauge, Ashley Scott, Chris Henry, Mark Scott, Sherry Herrmann, Tasha Skidmore, Melissa Thinner Hilbrands, Jason Spyksma, Jeff Hinsch, Sara Stientjes, Valerie Hoekstra, Christina Surma, Joe Hoogeveen, Kay Van Veldhuizen, Keri Hoppe, Lari Vande Kop, Holly Johnson, Lonette Vande Kop, Todd Kahl, Michael Venenga, Todd Kelderman, Jodi Vogl, Lissa Kix, Marla Vogl, Michelle Klinkenborg, Chris Warntjes, Wade Kooiker, Nolan Woodrow, Robert Central Lyon Class List 1991 Andy, Anderson Mantle, Mark Lewis, Anderson Matson, Sherry Rachel, Baatz McDonald, Chad Lyle, Bauer Miller, Bobby Darcy, Berg Miller, Penny Paul, Berg Moser, Jason Shane, Boeve Mowry, Lisa Borman, Zachary Mulder, Daniel Breuker, Theodore Olsen, Lisa Christians, Amy Popkes, Wade De Yong, Jana Rath, Todd Delfs, Rodney Rau, Gary Ellsworth, Jason Roths, June Fegan, Carrie Schillings, Roth Gardner, Sara Schubert, Traci Gingras, Cindy Scott, Chuck Goette, Holly Solheim, Bill Grafing, Jennifer Steenblock, Amy Grafing, Robin Stettnichs, -

Does God Ever Change His Mind About His Word? #1

Does God Ever Change His Mind About His Word? #1 ‘Carnal Impersonations; Corruption Setting In’ Bro. Lee Vayle - October 26, 1991 Shall we pray. Heavenly Father, we’re grateful that we always could count on Your Presence, by the fact that You are omniscient and omnipotent, but we realize in this hour as in the Exodus from Egypt into Canaan’s land that You came down to be with Your prophet. And then when Your prophet was off the scene, You moved the people in Yourself Lord, into the promised land and we know that our Joshua of this hour is the Lord Jesus Christ himself. And we appreciate that so much; the Holy Spirit doing the work, the Pillar of Fire leading us onward. We pray tonight, as we study Your Word, It shall…the very Life within It shall feed our souls, and enlighten our hearts and our minds and give us that extraordinary life Lord, which is of You in this particular hour to change mortality to immortality Lord. And we bring forth the dead out of the ground to take people away in a Rapture. We know that’s got to happen to somebody because it’s Your Word: it’s THUS SAITH THE LORD. The prophet already told us that the Shout was made available to us, everything under the Seals and the Thunders that was requisite to put us in the Rapture; we already had. And went on to tell us, we were already into the Resurrection. So Father, we believe tonight that is true and whatsoever, therefore, is necessary; the Life of the Word coming forth, that will come forth and we count ourselves a part of It in Jesus Christ’s Name, Amen. -

Notes on Numbers 202 1 Edition Dr

Notes on Numbers 202 1 Edition Dr. Thomas L. Constable TITLE The title the Jews used in their Hebrew Old Testament for this book comes from the fifth word in the book in the Hebrew text, bemidbar: "in the wilderness." This is, of course, appropriate since the Israelites spent most of the time covered in the narrative of Numbers in the wilderness. The English title "Numbers" is a translation of the Greek title Arithmoi. The Septuagint translators chose this title because of the two censuses of the Israelites that Moses recorded at the beginning (chs. 1—4) and toward the end (ch. 26) of the book. These "numberings" of the people took place at the beginning and end of the wilderness wanderings and frame the contents of Numbers. DATE AND WRITER Moses wrote Numbers (cf. Num. 1:1; 33:2; Matt. 8:4; 19:7; Luke 24:44; John 1:45; et al.). He apparently wrote it late in his life, across the Jordan from the Promised Land, on the Plains of Moab.1 Moses evidently died close to 1406 B.C., since the Exodus happened about 1446 B.C. (1 Kings 6:1), the Israelites were in the wilderness for 40 years (Num. 32:13), and he died shortly before they entered the Promised Land (Deut. 34:5). There are also a few passages that appear to have been added after Moses' time: 12:3; 21:14-15; and 32:34-42. However, it is impossible to say how much later. 1See the commentaries for fuller discussions of these subjects, e.g., Gordon J. -

Right Actions:Wrong Heart

Right Actions: Wrong Heart Page 1 of 3 RIGHT ACTIONS: WRONG HEART Numbers 22‐24 [page 228] INTRODUCTION Balaam was Mister Charisma. He was popular. o Tell story of his life. How he spoke for God. Why is a man who appears to be so right with God so villainously defamed throughout the rest of Scripture? o Right Actions: Wrong Heart . Identifying your hidden sin. Morally good. Inwardly bad. A heart check‐up for regular church people. Two people can appear to live identical lives, yet one may be living in unrighteousness/self‐righteousness and the other be living in Christ’s righteousness. The OT Judas. o 2Pe 2:15‐16 Which have forsaken the right way, and are gone astray, following the way of Balaam the son of Bosor, who loved the wages of unrighteousness; 16 ‐ But was rebuked for his iniquity: the dumb ass speaking with man's voice forbad the madness of the prophet. o Read Numbers 25:1 o Rev 2:14 But I have a few things against thee, because thou hast there them that hold the doctrine of Balaam, who taught Balac to cast a stumblingblock before the children of Israel, to eat things sacrificed unto idols, and to commit fornication. “Here, of course, Balaam is the type of a teacher of the church who attempts to advance the cause of God by advocating an unholy alliance with the ungodly and worldly, and so conforming the life of the church to the spirit of the flesh.” (ISBE) Balaam’s Character: “This may furnish us a clue to his character. -

Download Transcript

Naked Bible Podcast Episode 165: Q&A 22 Naked Bible Podcast Transcript Episode 165 Q&A 22 July 1, 2017 Teacher: Dr. Michael S. Heiser (MH) Host: Trey Stricklin (TS) Dr. Heiser answers your questions related to: Source material showing Jesus’ existence When a believer receives the Spirit of God Balaam’s error related to geography Seventy archangels in Jewish studies Theosis Which events in Genesis 1-11 are literal Whether Adam and Eve pooped Transcript TS: Welcome to the Naked Bible Podcast, Episode 165: our 22nd Q&A. I'm the layman, Trey Stricklin, and he's the scholar, Dr. Michael Heiser. Hey, Mike, how are you doing? MH: Pretty good, pretty good. Been staying busy, as usual. TS: Yeah. I just want to mention that we talked about how we were going to do our voting for the next book that we're going to cover on the podcast on July 1. We've added another interview, so we're actually going to start the voting on July 15th and run it through August 7th. That's when the voting's going to begin on the what the next book we're going to cover will be. MH: That's good. So in other words, I have a little more time to contact the Russians to have them influence the outcome of our vote, correct? TS: No comment on that. (laughter) The Russians or the Vatican, I don't know who you want to reach out to. The aliens? I don't know. MH: The Rosicrucians, the Templars.. -

Torah Stories the Mamas and the Papas Torah Family Tree

Bet (2nd Grade) Torah Stories The Mamas and the Papas Torah Family Tree Activity #1: To review from last year, read the 3 attached Bible stories about the mamas (matriarchs) and papas (patriarchs) of the Jewish people and/or read the character descriptions below. Using the Matriarch & Patriarch Family Tree Pictures page, cut out one set of character pictures and glue or tape them on the family tree in the correct place. Abraham- Known as the “father” of the Jewish people, Abraham is thought to be the first person to believe in ONE God. Abraham and his wife Sarah left their home to come to the land of Canaan to build a home for his children, grandchildren and future family members. Sarah- As the wife of Abraham, she left her home to help make a home for the Jewish people. Sarah gave birth to Isaac when she was old. Isaac- As son of Abraham and Sarah, Isaac led the Jewish people, after Abraham. Isaac and his wife Rebecca had twin sons, Jacob and Esau. Rebecca- Rebecca showed kindness by helping Isaac’s servant. She had twin sons, Jacob and Esau. Esau was strong and enjoyed hunting. Jacob stayed indoors helping with house chores. Rebecca thought Jacob should be the next leader of the Jewish people, even though it was Esau’s right as the older son. Rebecca helped Jacob trick Isaac. Isaac blessed Jacob instead of Esau and Jacob became the next leader. Jacob- Jacob was the clever, younger son of Isaac and Rebecca. With the help of his mother, Jacob became the next leader of the Jewish people. -

Numbers 17-22

The Weekly Word August 31- September 6, 2020 September is here… Fall, my favorite season of the year, will soon be with us. Happy reading… Grace and Peace, Bill To hear the Bible read click this link… http://www.biblegateway.com/resources/audio/. Monday, August 31: Numbers 17- How God led me to his grace… The Lord uses a creative miracle to mark His leadership for Israel. Sometimes a show of force is necessary. Sometimes other measures can be used. This is one of the latter cases. Korah’s rebellion resulted in the death of 14,600 Israelites. The earth swallowed up Korah and his followers. After that a plague ravaged the camp. I can only imagine that the plague bred fear in the camp. With this as the background I see the brilliance of God choosing a creative miracle to set Aaron apart. This miracle I imagine inspired awe and wonder. I know it did in me. Having a staff sprout, bud and flower! Spectacular! The Lord has so many ways to display His power and glory. Different ways connect with different people. I know people who have experienced healings and this led them to the Lord. I know others who had dreams that brought them to the Lord. Others came to believe in the Lord through the witness of a friend and still others believe in the Lord because of the faithful living of their parents and families. Different means for different people all guided by the one Lord God almighty. I sat and remembered the many means God used to lead me to Jesus. -

And This Is the Blessing)

V'Zot HaBerachah (and this is the blessing) Moses views the Promised Land before he dies את־ And this is the blessing, in which blessed Moses, the man of Elohim ְ ו ז ֹאת Deuteronomy 33:1 Children of Israel before his death. C-MATS Question: What were the final words of Moses? These final words of Moses are a combination of blessing and prophecy, in which he blesses each tribe according to its national responsibilities and individual greatness. Moses' blessings were a continuation of Jacob's, as if to say that the tribes were blessed at the beginning of their national existence and again as they were about to begin life in Israel. Moses directed his blessings to each of the tribes individually, since the welfare of each tribe depended upon that of the others, and the collective welfare of the nation depended upon the success of them all (Pesikta). came from Sinai and from Seir He dawned on them; He shined forth from יהוה ,And he (Moses) said 2 Mount Paran and He came with ten thousands of holy ones: from His right hand went a fiery commandment for them. came to Israel from Seir and יהוה ?present the Torah to the Israelites יהוה Question: How did had offered the Torah to the descendants of יהוה Paran, which, as the Midrash records, recalls that Esau, who dwelled in Seir, and to the Ishmaelites, who dwelled in Paran, both of whom refused to accept the Torah because it prohibited their predilections to kill and steal. Then, accompanied by came and offered His fiery Torah to the Israelites, who יהוה ,some of His myriads of holy angels submitted themselves to His sovereignty and accepted His Torah without question or qualification. -

Balaam and Balak

Unit 7 • Session 3 Use Week of: Unit 7 • Session 3 Balaam and Balak BIBLE PASSAGE: Numbers 22–24 STORY POINT: God commanded Balaam to bless His people. KEY PASSAGE: Proverbs 3:5-6 BIG PICTURE QUESTION: What does it mean to sin? To sin is to think, speak, or behave in any way that goes against God and His commands. • Countdown • Review (4 min.) • Introduce the session (2 min.) • Key passage (5 min.) • Big picture question (1 min.) • Group game (5–10 min.) • Giant timeline (1 min.) • Sing and give offering (3–12 min.) • Tell the Bible story (10 min.) • Missions moment (6 min.) • Christ connection • Announcements (2 min.) • Group demonstration (5 min.) • Prayer (2 min.) • Additional idea Additional resources are available at gospelproject.com. For free training and session-by- session help, visit www.ministrygrid.com/web/thegospelproject. Kids Worship Guide 34 Unit 7 • Session 3 © 2018 LifeWay LEADER Bible Study God’s people, the Israelites, were in the wilderness. They had arrived at the promised land decades earlier, but the people had rebelled—refusing to trust God to give them the land. They believed it would be better to die in the wilderness than follow God (Num. 14:2), so God sent them into the wilderness for 40 years (vv. 28-29). In time, all of the adults died except for Joshua, Caleb, and Moses. The children grew up and more children were born. The Israelites disobeyed God time and again, but God still provided for them. He planned to keep His promise to give Israel the promised land.