Executive Summary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Politics of Military Reform in Post-Suharto Indonesia: Elite Conflict, Nationalism, and Institutional Resistance

Policy Studies 23 The Politics of Military Reform in Post-Suharto Indonesia: Elite Conflict, Nationalism, and Institutional Resistance Marcus Mietzner East-West Center Washington East-West Center The East-West Center is an internationally recognized education and research organization established by the U.S. Congress in 1960 to strengthen understanding and relations between the United States and the countries of the Asia Pacific. Through its programs of cooperative study, training, seminars, and research, the Center works to promote a stable, peaceful, and prosperous Asia Pacific community in which the United States is a leading and valued partner. Funding for the Center comes from the U.S. government, private foundations, individuals, cor- porations, and a number of Asia Pacific governments. East-West Center Washington Established on September 1, 2001, the primary function of the East- West Center Washington is to further the East-West Center mission and the institutional objective of building a peaceful and prosperous Asia Pacific community through substantive programming activities focused on the theme of conflict reduction, political change in the direction of open, accountable, and participatory politics, and American understanding of and engagement in Asia Pacific affairs. The Politics of Military Reform in Post-Suharto Indonesia: Elite Conflict, Nationalism, and Institutional Resistance Policy Studies 23 ___________ The Politics of Military Reform in Post-Suharto Indonesia: Elite Conflict, Nationalism, and Institutional Resistance _____________________ Marcus Mietzner Copyright © 2006 by the East-West Center Washington The Politics of Military Reform in Post-Suharto Indonesia: Elite Conflict, Nationalism, and Institutional Resistance by Marcus Mietzner ISBN 978-1-932728-45-3 (online version) ISSN 1547-1330 (online version) Online at: www.eastwestcenterwashington.org/publications East-West Center Washington 1819 L Street, NW, Suite 200 Washington, D.C. -

Tembok Tebal, Pengusutan Pembunuhan Munir

Tembok Tebal, Pengusutan Pembunuhan Munir Sebuah Analisis Kebijakan Tim Imparsial September 2006 BAB I ”TEST OF OUR HISTORY” ”..... sejauh pengadilan HAM tidak becus, maka itu merupakan kepanjangan tangan masa lalu” (Munir 1965-2004) Proses pengungkapan kasus pembunuhan politik terhadap Munir berjalan kembali ke titik nol. Menjelang dua (2) tahun pasca pembunuhan politik terhadap Munir, 7 September 2004, belum terdapat titik terang yang menunjukkan motif dan para pelaku pembunuhan sebenarnya. Bahkan penyelidikan pasca berakhirnya masa kerja Tim Pencari Fakta (TPF) nyaris tidak memberikan perkembangan berarti bagi kasus tersebut. Pasca putusan Pengadilan Negeri Jakarta Pusat 20 Desember 2005 dengan nomor 1361/Pid/B/2005/PN.Jkt.Pst, yang memutuskan hukuman 14 tahun penjara bagi Pollycarpus Budihari Priyanto, pihak terdakwa mengajukan banding. Pada 27 Maret 2006, Pengadilan Tinggi Jakarta Pusat memutuskan menerima banding yang diajukan Pollycarpus dan menguatkan putusan Pengadilan Negeri Jakarta Pusat, yakni tetap menghukum Pollycarpus dengan 14 tahun penjara. Penyelidikan kepolisian yang setengah hati dan terkesan menemui buntu, padahal banyak informasi yang dapat ditindak lanjuti, misalnya hubungan telpon antara Muchdi, BIN, dan Pollycarpus. Pergantian pimpinan penyelidik yang sudah dilakukan sebanyak tiga (3) kali, belum memberikan perkembangan. Malah semakin berjalan lamban bila dibandingkan dengan hasil temuan dari tim penyelidik kepolisian terdahulu. Semasa hidupnya, advokasi yang dilakukan oleh Munir memang tidak pernah lepas dari persinggungan dengan pihak militer. Sewaktu Munir menangani kasus pembunuhan terhadap Marsinah, ia tidak hanya diancam oleh aparat kodam setempat (Brawijaya) tapi juga diancam akan dihilangkan nyawanya lantaran melibatkan diri dalam urusan kematian buruh pabrik di Sidoarjo tersebut.1 Bahkan, di lain kesempatan, Munir berani menantang para pelaku pelanggar HAM –terutama dari pihak militer- secara terbuka, di mana dalam sebuah aksi bersama keluarga korban di 1 Forum Keadilan,” Mantan Pedagang Melawan Kekerasan”, No. -

General Assembly Distr.: General 22 February 2010

United Nations A/HRC/13/NGO/40 General Assembly Distr.: General 22 February 2010 English only Human Rights Council Thirteenth session Agenda item 3 Promotion and protection of all human rights, civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights, including the right to development Written statement* submitted by the International NGO Forum on Indonesian Development (INFID), a non- governmental organization in special consultative status The Secretary-General has received the following written statement which is circulated in accordance with Economic and Social Council resolution 1996/31. [15 February 2010] * This written statement is issued, unedited, in the language(s) received from the submitting non- governmental organization(s). GE.10-11176 A/HRC/13/NGO/40 Situation of human rights defenders in Indonesia 20091 The situation of Human Rights Defenders in 2009 is worse compared to 2008, because in 2009 many defenders were criminalized by the government. The journalist of Radar Bali, Anak Agung Prabangsa, in February 2009 killed by the candidate of the local parliament in Bali after he wrote about corruption that allegedly done by the perpetrator2. Hendra Budian, Director of Aceh Judicial Monitoring Institute (AJMI) Banda Aceh alleged by the Office of Province Attorney Nanggroe Aceh Darrusalam as criminal by ruining glass window of the Office of the Province Attorney. Hendra is charged against article 406 Indonesia Penal Code. His case is in Banda Aceh District Court now.3 On 5 May 2009, Constitutional Court rejected the review of the Independence Journalist Alliance on article 27 (3) Law on the Information and Electronic Transaction Nr. 11 year 2008.4 On 13 May 2009, SCTV’s reporter Carlos Pardede attacked by security staff of the Bank of Indonesia. -

Power Politics and the Indonesian Military

Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 20:05 09 May 2016 Power Politics and the Indonesian Military Throughout the post-war history of Indonesia, the military has played a key role in the politics of the country and in imposing unity on a fragmentary state. The collapse of the authoritarian New Order government of President Suharto weakened the state, and the armed forces briefly lost their grip on control of the archipelago. Under President Megawati, however, the military has again begun to assert itself, and to reimpose its heavy hand on control of the state, most notably in the fracturing outer provinces. This book, based on extensive original research, examines the role of the military in Indonesian politics. It looks at the role of the military histori- cally, examines the different ways in which it is involved in politics, and considers how the role of the military might develop in what is still an uncertain future. Damien Kingsbury is Head of Philosophical, International and Political Studies and Senior Lecturer in International Development at Deakin University, Victoria, Australia. He is the author or editor of several books, including The Politics of Indonesia (Second Edition, 2002), South-East Asia: A Political Profile (2001) and Indonesia: The Uncertain Transition (2001). His main area of work is in political development, in particular in assertions of self-determination. Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 20:05 09 May 2016 Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 20:05 09 May 2016 Power Politics and the Indonesian Military Damien Kingsbury Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 20:05 09 May 2016 First published 2003 by RoutledgeCurzon 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by RoutledgeCurzon 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 This edition published in the Taylor and Francis e-Library, 2005. -

Issues for Congress

Papua, Indonesia: Issues for Congress January 19, 2006 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RL33260 Papua, Indonesia: Issues for Congress Summary The ongoing investigation into the killing of two American citizens, current human rights conditions, and reports of an Indonesian military build-up in Papua have led to increased Congressional attention to Indonesia’s eastern-most territory. Papua, for the purposes of this report, refers to the resource rich western half of the island of New Guinea and not the nation or people of Papua New Guinea which is situated on the eastern half of the Island. While the people of Papua have been subject to human rights abuses while under Indonesian rule, the ongoing expansion of democracy and civil society in Indonesia and the leadership of President Yudhoyono hold out the possibility that the human rights situation in Papua may improve. Some view the current improvement in the bilateral relationship between the United States and Indonesia as providing an enhanced opportunity for the United States to continue to support the expansion of democracy, the rule of law, civil society, and human rights while developing closer military-to- military relations with a valuable partner in the war against terror and a key geopolitical actor in the Southeast Asian region. Such policies, by fostering a more democratic and open society, may also contribute to an improved human rights situation in Papua. Others, including some Members of Congress, contend that Indonesia’s failure thus far to bring to trial those responsible for the Timika incident and other human rights abuses, suggests that the Indonesian military (TNI) remains, at least in part, outside government control and that the United States should continue to suspend some kinds of military assistance. -

Indonesian Politics in Crisis

Indonesian Politics in Crisis NORDIC INSTITUTE OF ASIAN STUDIES Recent and forthcoming studies of contemporary Asia Børge Bakken (ed.): Migration in China Sven Cederroth: Basket Case or Poverty Alleviation? Bangladesh Approaches the Twenty-First Century Dang Phong and Melanie Beresford: Authority Relations and Economic Decision-Making in Vietnam Mason C. Hoadley (ed.): Southeast Asian-Centred Economies or Economics? Ruth McVey (ed.): Money and Power in Provincial Thailand Cecilia Milwertz: Beijing Women Organizing for Change Elisabeth Özdalga: The Veiling Issue, Official Secularism and Popular Islam in Modern Turkey Erik Paul: Australia in Southeast Asia. Regionalisation and Democracy Ian Reader: A Poisonous Cocktail? Aum Shinrikyo’s Path to Violence Robert Thörlind: Development, Decentralization and Democracy. Exploring Social Capital and Politicization in the Bengal Region INDONESIAN POLITICS IN CRISIS The Long Fall of Suharto 1996–98 Stefan Eklöf NIAS Nordic Institute of Asian Studies Studies in Contemporary Asia series, no. 1 (series editor: Robert Cribb, University of Queensland) First published 1999 by NIAS Publishing Nordic Institute of Asian Studies (NIAS) Leifsgade 33, 2300 Copenhagen S, Denmark Tel: (+45) 3254 8844 • Fax: (+45) 3296 2530 E-mail: [email protected] Online: http://nias.ku.dk/books/ Typesetting by the Nordic Institute of Asian Studies Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International Limited, Padstow, Cornwall © Stefan Eklöf 1999 British Library Catalogue in Publication Data Eklof, Stefan Indonesian politics -

1998 Human Rights Report - Indonesia Page 1 of 37

1998 Human Rights Report - Indonesia Page 1 of 37 The State Department web site below is a permanent electronic archive of information released prior to January 20, 2001. Please see www.state.gov material released since President George W. Bush took office on that date. This site is not updated so external links may no longer function. Contact us with any questions about finding information. NOTE: External links to other Internet sites should not be construed as an endorsement of the views contained therein. U.S. Department of State Indonesia Country Report on Human Rights Practices for 1998 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, February 26, 1999. INDONESIA Indonesia's authoritarian political system came under sustained challenge during 1998, resulting in President Soeharto's departure from office and opening an opportunity for meaningful political and economic reforms. The ultimate result of this reform effort remains unclear. Two months after his reelection to a seventh 5-year term in March, popular pressure forced Soeharto to resign in favor of his hand-picked Vice President, B.J. Habibie. The new President immediately announced a series of steps to address domestic and international human rights concerns. With many citizens questioning his legitimacy because of his close association with Soeharto, President Habibie formed a cabinet that drew heavily on holdovers from the last Soeharto Cabinet. In response to demands for early elections, Habibie pledged to advance parliamentary elections by 3 years, to hold them under fundamentally revised electoral laws, and to complete selection of a new president by the end of 1999. -

Election Update Issue 2, Oct/Nov 2008

Election Update Issue 2, Oct/Nov 2008 The Multi-Choice Elections 2009 will be an important year for reformasi in Indonesia, which began in 1998 after the downfall of the dictatorial Suharto regime. On 9 April 2009, elections will be held for the Indonesian Parliament, the DPR (Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat, People’s Representative Assembly), the DPD (Dewan Perwakilan Daerah, Regional Representatives Council) and provincial assemblies. Three months later, the first round of direct elections will be held for the President and Vice-President. No fewer than 38 political parties will participate in the legislative elections. Just ten years ago, Indonesia emerged from what was in effect a one-party system. The bicameral system of Indonesian Parliament became increasingly powerless. governance is only five years old, following the creation of the DPD, first elected in 2004. The MPs were only allowed to rubber-stamp new DPD is composed of four representatives from laws. Serious discussions were seen as a each province, all non-party independents. It hindrance to authoritarian rule. has the right to make proposals and submit opinions on legislative matters and monitor the As is the case under the US presidential implementation of laws, but it does not yet system, members of the government are have the revising function of second chambers appointees of the President. In Indonesia, they in other countries such as the (unelected) are not directly answerable to parliament House of Lords in the UK or the US Senate. though they can be, and frequently are, There is growing unease about what some summoned to give an account of their policies lawyers and politicians regard as the and actions to parliamentary committees. -

The Discourse System Recognized in the Jakarta Post's Opinion

Mashlihatul Umami The Discourse System Recognized In The JaNarta 3ost‘s Opinion Coloumn Entitled —Polycarpus Out On Parole: Resolve Munir‘s Case“ On December 05th, 2014 Mashlihatul Umami Sekolah Tinggi Agama Islam Negeri (STAIN) Salatiga Jl. Tentara Pelajar No.02 Salatiga, Central Java, Indonesia [email protected] Abstract This study attempts to construe the discourse devices recognized in the article of Jakarta Post opinion column entitle —Polycarpus out on Parole: Resolve Munir‘s Case“ on December 05th, 2014 using meta-function strategy proposed by Martin and White (2005). The researcher found that the opinion text displays meta-function devices in different ways by using appraisal, ideation, conjunction, identification and periodicity to express their opinion with the related issue. The biggest parts used in appraisal are affect-attitude, judgment-attitude, and appreciation-attitude, force-graduation and focus-graduation. Besides using mono-gloss, the writers of the article also use hetero-gloss by projection, modality and concession or counter-expectancy. In the aspect of ideation, the researcher found that there are four kinds of figures, respectively, ‘doing, saying, sensing, and being. In terms of conjunction, it has been found that the writers of article use external and internal conjunction. To keep track of what is being talked about to the readers, the writers of article using ideation strategies by presenting, presuming, possessive, comparative, and text. At last, in terms of periodicity, the writers use themes, marked themes, -

INDONESIA Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders Annual Report 2011

INDONESIA OBSERVATORY FOR thE PROTEctiON OF humAN Rights DEFENDERS ANNUAL REPORT 2011 In a climate of impunity, human rights defenders documenting human rights violations by the police as well as incidents of corruption or environmental rights were subjected to attacks, including assassination and attempted assassination. Non-State actors, in particular extremist religious groups, were responsible for an increasing number of threats, harassments and intimidations to human rights defenders throughout the year, often accompanied with complicity of police officials. In particular, lawyers who take up cases related to blasphemy and religious minorities also faced acts of harass- ment and intimidation by non-State actors. As intolerance towards sexual minorities increased, freedom of assembly of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Intersex (LGBTI) activists was curtailed on several occasions. Political context No significant improvement was seen1 in the field of human rights. Accountability for past-Reformasi era crimes remained low and public security2 and confidence in the police continued to erode during the course of 2010 . Members of the police and military continued to enjoy an almost complete immunity from serious investigations and prosecutions. In addi- tion, in the few cases that3 were prosecuted they resulted in disproportion- ately lenient sentences . Impunity for human rights violations committed during the Suharto era also remained the rule, with no high-level military figures having been con- victed. The culture of impunity was accompanied with ambiguous politi- cal messages by the Government. On March 22, 2010, Defence Minister Purnomo Yusgiantoro pledged to suspend soldiers credibly accused of serious human rights violations, to cooperate with their prosecution, and to discharge those convicted. -

SHADOWS and CLOUDS Human Rights in Indonesia – Shady Legacy, Uncertain Future

SHADOWS AND CLOUDS Human Rights in Indonesia – shady legacy, uncertain future of person. Article 4: No one shall be held in slavery Article 1: All human beings are born free and equal or servitude; slavery and the slave trade shall be prohibited in all their forms. Article 5: No one shall be subjected to in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. Article 6: Everyone has the right to recognition spirit of brotherhood. Article 2: Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, everywhere as a person before the law. Article 7: All are equal before the law and are entitled without any discrimi- without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, nation to equal protection of the law. All are entitled to equal protection against any discrimination in violation of this national or social origin, property, birth or other status. Furthermore, no distinction shall be made on the Declaration and against any incitement to such discrimination. Article 8: Everyone has the right to an effective rem- basis of the political, jurisdictional or international status of the country or territory to which a person edy by the competent national tribunals for acts violating the fundamental rights granted him by the constitution or belongs, whether it be independent, trust, non-self-governing or under any other limitation of sovereignty. by law. Article 9: No one shall be subjected to arbitrary arrest, Article 3: Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security December 2010 N°552a H SHADOWS AND CLOUDS Human Rights in Indonesia – shady legacy, uncertain future © Holt Rinehart Winston World Atlas Cover: © courtesy of KontraS Ho Kim Ngo, mother of one of the 16 student activists who were allegedly killed by the Police in the 1999 Semanggi II incident, calling on the government to deliver justice for her son. -

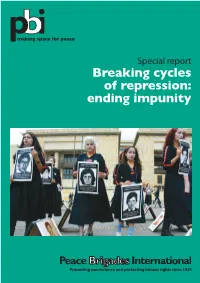

Special Report on Impunity

making space for peace Special report Promoting nonviolence and protecting human rights since 1981 PBI is an international NGO that has been ¤ ¥ ¦ § ¨ ¦ © © ¨ protecting human rights and promoting £ § ¦ © © © nonviolence since 1981. On request, we send § teams of international volunteers to areas of © ¨ © § © ¨ § repression and confl ict to provide an international § ¨ © ¨ § ¨ ¨ § ¨ ¨ § ¨ presence and protective accompaniment to © ¨ ¦ © © © § ¨ © local human rights defenders, civil society © ¨ ¨ © organisations and communities whose lives and ¨ work are threatened by political violence. Our ¦ © ¨ © ¦ § © © © § © work is based on the principles of nonviolence, § © ¥ ¦ § ¨ © § © ¦ § © non partisanship and non-interference in © © § © ¨ § ¦ © the internal affairs of the organisations we § ¦ © ¦ § © © ! ¦ © © accompany and the belief that transformation of confl icts cannot be imposed from outside. ¦ § © © © © ¦ § § § ¨ PBI teams physically accompany those at § § ¨ ¨ ¦ © £ ¤ ¥ ¦ § ¨ risk. The volunteers represent international © © © ¨ © Felipe Arreaga Sanchez accompanied by concern for the protection of human rights, a PBI Mexico volunteer visible reminder to the perpetrators of violence " # $ #% & % ' ( # ) * + , - . / 0 1 2 3 , 4 5 6 / 7 8 9 1 + : ; ; ; ; ; < 1 / 4 2 0 = 1 > - ? 2 @ 2 / 6 A 1 9 9 ? . + B 9 ? 9 6 6 C 0 + that their actions will have repercussions 1 : ; ; . D 2 / We dedicate this publication