"'Pop' Goes Hawaii: the 20Th Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

James Albert Michener (1907-97): Educator, Textbook Editor, Journalist, Novelist, and Educational Philanthropist--An Imaginary Conversation

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 474 132 SO 033 912 AUTHOR Parker, Franklin; Parker, Betty TITLE James Albert Michener (1907-97): Educator, Textbook Editor, Journalist, Novelist, and Educational Philanthropist--An Imaginary Conversation. PUB DATE 2002-00-00 NOTE 18p.; Paper presented at Uplands Retirement Community (Pleasant Hill, TN, June 17, 2002). PUB TYPE Opinion Papers (120) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Authors; *Biographies; *Educational Background; Popular Culture; Primary Sources; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS *Conversation; Educators; Historical Research; *Michener (James A); Pennsylvania (Doylestown); Philanthropists ABSTRACT This paper presents an imaginary conversation between an interviewer and the novelist, James Michener (1907-1997). Starting with Michener's early life experiences in Doylestown (Pennsylvania), the conversation includes his family's poverty, his wanderings across the United States, and his reading at the local public library. The dialogue includes his education at Swarthmore College (Pennsylvania), St. Andrews University (Scotland), Colorado State University (Fort Collins, Colorado) where he became a social studies teacher, and Harvard (Cambridge, Massachusetts) where he pursued, but did not complete, a Ph.D. in education. Michener's experiences as a textbook editor at Macmillan Publishers and in the U.S. Navy during World War II are part of the discourse. The exchange elaborates on how Michener began to write fiction, focuses on his great success as a writer, and notes that he and his wife donated over $100 million to educational institutions over the years. Lists five selected works about James Michener and provides a year-by-year Internet search on the author.(BT) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

Reading the Novel of Migrancy

Reading the Novel of Migrancy Sheri-Marie Harrison Abstract This essay argues that novels like Marlon James’s A Brief History of Seven Killings, Viet Thanh Nguyen’s The Sympathizer, Colson Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad, and Mohsin Hamid’s Exit West exemplify a new form of the novel that does not depend on national identification, but is instead organized around the transnational circulation of people and things in a manner that parallels the de- regulated flow of neoliberal capital. In their literal depiction of the movement of people across borders, these four very different novels collectively address the circulation of codes, tropes, and strategies of representation for particular ethnic and racial groups. Moreover, they also address, at the level of critique, the rela- tionship of such representational strategies to processes of literary canonization. The metafictional and self-reflexive qualities of James’s and Nguyen’s novels con- tinually draw the reader’s attention to the politics of reading and writing, and in the process they thwart any easy conclusions about what it means to write about conflicts like the Vietnam war or the late 1970s in Jamaica. Likewise, despite their different settings Hamid’s Exit West and Whitehead’s Underground Railroad are alike in that they are both about the movement of stateless people across borders and both push the boundaries of realism itself by employing non-realistic devices as a way of not representing travel across borders. In pointing to, if not quite il- luminating, the “dark places of the earth,” the novel of migrancy thus calls into existence, without really representing, conditions for a global framework that does not yet exist. -

Elvis Presley for Ukulele Ebook

ELVIS PRESLEY FOR UKULELE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jim Beloff | 72 pages | 21 Mar 2011 | Hal Leonard Corporation | 9781423465560 | English | Milwaukee, United States Elvis Presley for Ukulele PDF Book Shipping Information. Dirty, Dirty Feeling. Swing Down Sweet Chariot. Essential Elements Ukulele. See details. Baby I Don't Care. Little Egypt. Stuck on You. Sheet music Poster. Talk About The Good Times. Starting Today. Skip to the beginning of the images gallery. For a better shopping experience, please upgrade now. Sweet Angeline. This Is The Story. Paralyzed chr? That's All Right, Mama. He Touched Me. Playing For Keeps chr? It's Now or Never. A week, one-lick-per-day workout program for developing, improving, and maintaining baritone ukulele technique. Let It Be Me. It displays all chords in six tunings for the different sizes of the ukulele. Skip to the end of the images gallery. We will charge no extra to restring it. In The Garden. My Wish Came True Ukulele. You've been through Fast Track Ukulele 1 several times, and you're Five Sleepy Heads. I Got Lucky chr? Known Only To Him. It's Now Or Never. Blue Suede Shoes. All packages will be shipped with a signature requirement by default. Customer Questions. Beginner tabs. Notify me when this product is in stock. One Broken Heart For Sale chr? The accompanying CD contains 51 tracks of songs for demonstration and play along. Home 1 Books 2. Elvis Presley for Ukulele Writer Blue River chr 8 Blue Suede Shoes mix? Always on my mind. Amazing Grace. We're passionate about music, we're also highly experienced in all technical matters for the musical instruments we provide. -

JAMES A. MICHENER Has Published More Than 30 Books

Bowdoin College Commencement 1992 One of America’s leading writers of historical fiction, JAMES A. MICHENER has published more than 30 books. His writing career began with the publication in 1947 of a book of interrelated stories titled Tales of the South Pacific, based upon his experiences in the U.S. Navy where he served on 49 different Pacific islands. The work won the 1947 Pulitzer Prize, and inspired one of the most popular Broadway musicals of all time, Rodgers and Hammerstein’s South Pacific, which won its own Pulitzer Prize. Michener’s first book set the course for his career, which would feature works about many cultures with emphasis on the relationships between different peoples and the need to overcome ignorance and prejudice. Random House has published Michener’s works on Japan (Sayonara), Hawaii (Hawaii), Spain (Iberia), Southeast Asia (The Voice of Asia), South Africa (The Covenant) and Poland (Poland), among others. Michener has also written a number of works about the United States, including Centennial, which became a television series, Chesapeake, and Texas. Since 1987, the prolific Michener has written five books, including Alaska and his most recent work, The Novel. His books have been issued in virtually every language in the world. Michener has also been involved in public service, beginning with an unsuccessful 1962 bid for Congress. From 1979 to 1983, he was a member of the Advisory Council to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, an experience which he used to write his 1982 novel Space. Between 1978 and 1987, he served on the committee that advises that U.S. -

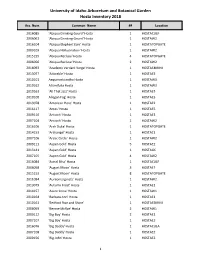

University of Idaho Arboretum and Botanical Garden Hosta Inventory 2018

University of Idaho Arboretum and Botanical Garden Hosta Inventory 2018 Acc. Num. Common Name ## Location 2016085 'Abiqua Drinking Gourd' Hosta 1 HOSTACULF 2006061 'Abiqua Drinking Gourd' Hosta 1 HOSTAW2 2016104 'Abiqua Elephant Ears' Hosta 1 HOSTATOPGATE 2009109 'Abiqua Hallucination' Hosta 1 HOSTAW2 2015155 'Abiqua Recluse' Hosta 4 HOSTATOPGATE 2006056 'Abiqua Recluse' Hosta 2 HOSTAW2 2016093 'Academy Verdant Verge' Hosta 1 HOSTAE4MINI 2013077 'Adorable' Hosta 1 HOSTAE3 2010101 Aequinoctiiantha Hosta 1 HOSTAW3 2010162 Alismifolia Hosta 1 HOSTAW3 2010163 'All That Jazz' Hosta 1 HOSTAE5 2010100 Allegan Fog' Hosta 1 HOSTAE3 2013078 'American Hero' Hosta 1 HOSTAE2 2016117 'Amos' Hosta 1 HOSTAE5 2009110 'Antioch' Hosta 1 HOSTAE3 2007104 'Antioch' Hosta 1 HOSTAW2 2016106 'Arch Duke' Hosta 1 HOSTATOPGATE 2014153 'Archangel' Hosta 1 HOSTAE1 2007106 'Arctic Circle ' Hosta 1 HOSTAW2 2009111 'Aspen Gold' Hosta 5 HOSTAE2 2013141 'Aspen Gold' Hosta 1 HOSTAGC 2007105 'Aspen Gold' Hosta 4 HOSTAW2 2016084 'Astral Bliss' Hosta 1 HOSTACULF 2006058 'August Moon' Hosta 3 HOSTAE1 2015153 'August Moon' Hosta 8 HOSTATOPGATE 2011094 'Aureomarginata' Hosta 1 HOSTAW2 2013079 'Autumn Frost' Hosta 1 HOSTAE1 2014157 'Azure Snow' Hosta 1 HOSTAW1 2010164 'Barbara Ann' Hosta 1 HOSTAE1 2010161 'Bedford Rise and Shine' 1 HOSTAE5MINI 2006059 'Bennie McRae' Hosta 2 HOSTAW1 2009112 'Big Boy' Hosta 2 HOSTAE1 2007107 'Big Boy' Hosta 1 HOSTAE2 2016076 'Big Daddy' Hosta 1 HOSTACULA 2007108 'Big Daddy' Hosta 1 HOSTAE2 2009156 'Big John' Hosta 1 HOSTAE3 1 University of Idaho -

A Community of Contrasts: Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders in Orange County Addresses This Critical Challenge by Doing Two Things

2014 A COMMUNITY Cyrus Chung Ying Tang Foundation OF CONTRASTS Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders in Orange County ORANGE www.calendow.org COUNTY This report was made possible by the following sponsors: The Wallace H. Coulter Foundation, Cyrus Chung Ying Tang Foundation, Wells Fargo, and The California Endowment. The statements and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors. CONTENTS ORGANIZATIONAL DESCRIPTIONS TECHNICAL NOTES Welcome 1 Introduction 2 Executive Summary 3 Map 5 Measuring the characteristics of racial and ethnic groups Demographics 6 Since 2000, the United States Census Bureau has allowed those responding to its questionnaires to report one or more Asian Americans Advancing Justice - Orange County Economic Contributions 9 racial or ethnic backgrounds. While this better reflects America’s diversity and improves data available on multiracial popula- The mission of Asian Americans Advancing Justice (“Advancing Civic Engagement 10 tions, it complicates the use of data on racial and ethnic groups. Justice”) is to promote a fair and equitable society for all by Immigration 12 working for civil and human rights and empowering Asian Language 14 Data on race are generally available from the Census Bureau in two forms, for those of a single racial background (referred Americans and Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders (NHPI) Education 16 to as “alone”) with multiracial people captured in an independent category, and for those of either single or multiple racial and other underserved communities. -

Ke Kumu: Strategic Directions for Hawaii's Tourism Industry

Hawaiÿi Tourism Strategic Plan: 2005-2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .....................................................................................................................1 TOURISM IN HAWAIÿI.............................................................................................................3 VISION .....................................................................................................................................6 GUIDING PRINCIPLES AND VALUES ......................................................................................7 IMPLEMENTATION FRAMEWORK ...........................................................................................8 MEASURES OF SUCCESS .......................................................................................................10 STRATEGIC DIRECTIONS.......................................................................................................13 Access ..........................................................................................................................14 Communications and Outreach ....................................................................................21 Hawaiian Culture..........................................................................................................25 Marketing .....................................................................................................................30 Natural Resources.........................................................................................................36 -

Chartbook on Healthcare for Asians and Native Hawaiians/Pacific Islanders

Chartbook on Healthcare for Asians and Native Hawaiians/Pacific Islanders NATIONAL HEALTHCARE QUALITY AND DISPARITIES REPORT This document is in the public domain and may be used and reprinted without permission. Citation of the source is appreciated. Suggested citation: National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report Healthcare for Asians and Native Hawaiians/Pacific Islanders. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; May 2020. AHRQ Pub. No. 20-0043. National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report Chartbook on Healthcare for Asians and Native Hawaiians/Pacific Islanders Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality 5600 Fishers Lane Rockville, MD 20857 www.ahrq.gov AHRQ Publication No. 20-0043 May 2020 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report (QDR) is the product of collaboration among agencies across the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Many individuals guided and contributed to this effort. Without their magnanimous support, this chartbook would not have been possible. Specifically, we thank: Authors: • AHRQ: Barbara Barton, Celeste Torio, Bill Freeman, Brenda Harding, Erofile Gripiotis • SAMHSA: Victoria Chau • Health Services Advisory Group (HSAG): Robert Fornango, Paul Niemann, Michael Lichter, Cindy Strickland, Mitchell Keener, Fredericka Thompson Primary AHRQ Staff: Gopal Khanna, David Meyers, Jeff Brady, Francis Chesley, Erin Grace, Kamila Mistry, Celeste Torio, Karen Chaves, Barbara Barton, Bill Freeman, Erofile Gripiotis, Brenda Harding, Irim Azam, Tahleah Chappel, Doreen Bonnett. HHS Interagency Workgroup for the QDR: Irim Azam (AHRQ/CQuIPS), Girma Alemu (HRSA), Doreen Bonnett (AHRQ/OC), Deron Burton (CDC/DDID/NCHHSTP/OD), Victoria Chau (SAMHSA), Karen H. Chaves (AHRQ), Christine Lee (FDA), Deborah Duran (NIH/NIMHD), Ernest Moy (VA), Melissa Evans (CMS/CCSQ), Camille Fabiyi (AHRQ/OEREP), Darryl Gray (AHRQ/CQuIPS), Kirk Greenway (IHS/HQ), Sarah Heppner (HRSA), Edwin D. -

Blue Hawaii Blue Hawaii As Turquoise As a Tropical Lagoon, Ingredients This Taste Explosion Was Created by Bartender Harry Yee at the Hilton ¾ Oz

Blue Hawaii Blue Hawaii As turquoise as a tropical lagoon, Ingredients this taste explosion was created by bartender Harry Yee at the Hilton ¾ oz. White Rum; ¾ oz. Vodka; Hotel in Honolulu in 1957. A sales rep from an Amsterdam distillery ¾ oz. Blue Curaçao; introduced Yee to the first bottle of 3 oz. Fresh Pineapple Juice; Blue Curaçao ever to reach the 1 oz. Fresh Sour Mix (see recipe islands. A true Blue Hawaii is meant below) to be built rather than shaken, as For garnish: Fresh Pineapple Yee was known to layer all the Wedge & Maraschino Cherry ingredients into an individual hurricane glass filled with ice, give it Fill a hurricane glass with ice cubes. a stir and then hold up each finished Pour in each ingredient and stir with drink to compare its shade of blue to a tall spoon. Slice a notch in the the Pacific Ocean outside the pineapple wedge and fit onto the lip window. Not to be confused with of the glass. For a frozen drink, pulse another luau drink the all ingredients in the blender until Blue Hawaiian which includes smooth before pouring into a glass. coconut cream, the Blue Hawaii was invented four years before Elvis For Fresh Sour Mix: Presley ever danced the hula in a movie of the same name. 1 C simple syrup:= Interestingly enough, no one 1 c water+1C sugar consumes a Blue Hawaii in Blue Boil to dissolve sugar and let Hawaii but loads of happy people have enjoyed them for decades all cool then add over the world. -

Environmental Justice, Indigenous Knowledge Systems, and Native Hawaiians and Other Pacific Islanders

Wayne State University Human Biology Open Access Pre-Prints WSU Press 10-9-2020 Environmental Justice, Indigenous Knowledge Systems, and Native Hawaiians and Other Pacific Islanders Michael S. Spencer University of Washington Taurmini Fentress University of Washington Ammara Touch University of Washington Jessica Hernandez University of Washington Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/humbiol_preprints Recommended Citation Spencer, Michael S.; Fentress, Taurmini; Touch, Ammara; and Hernandez, Jessica, "Environmental Justice, Indigenous Knowledge Systems, and Native Hawaiians and Other Pacific Islanders" (2020). Human Biology Open Access Pre-Prints. 176. https://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/humbiol_preprints/176 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the WSU Press at DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Human Biology Open Access Pre-Prints by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. Environmental Justice, Indigenous Knowledge Systems, and Native Hawaiians and Other Pacific Islanders Michael S. Spencer,1,2,* Taurmini Fentress,1 Ammara Touch,3,4 Jessica Hernandez5 1School of Social Work, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA. 2Indigenous Wellness Research Institute (IWRI), University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA. 3College of the Arts & Sciences, Department of Biology, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA. 4College of the Arts & Sciences, Department of American Ethnic Studies, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington USA. 5School of Environmental and Forest Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA. *Correspondence to: Mike Spencer, University of Washington School of Social Work, Box 354900, Seattle, Washington 98195-4900 USA. E-mail: [email protected]. Short Title: Environmental Justice and Pacific Islanders KEY WORDS: NATIVE HAWAIIAN, PACIFIC ISLANDERS, ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE, INDIGENOUS KNOWLEDGE, TRADITIONAL ECOLOGICAL KNOWLEDGE, SETTLER COLONIALISM. -

Redalyc.Integrating Sustainability and Hawaiian Culture Into the Tourism

PASOS. Revista de Turismo y Patrimonio Cultural ISSN: 1695-7121 [email protected] Universidad de La Laguna España Agrusa, Wendy; Lema, Joseph; Tanner, John; Host, Tanya; Agrusa, Jerome Integrating Sustainability and Hawaiian Culture into the Tourism Experience of the Hawaiian Islands PASOS. Revista de Turismo y Patrimonio Cultural, vol. 8, núm. 2, 2010, pp. 247-264 Universidad de La Laguna El Sauzal (Tenerife), España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=88112768001 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Vol. 8 Nº2 págs. 247-264. 2010 www.pasosonline.org Integrating Sustainability and Hawaiian Culture into the Tourism Experience of the Hawaiian Islands Wendy Agrusaii Hawaii Pacific University (EEUU) Joseph Lemaiii Drexel University (EEUU) John Tanneriv University of Louisiana at Lafayette (EEUU) Tanya Hostv Hawaii Pacific University (EEUU) Jerome Agrusavi Hawaii Pacific University (EEUU) Abstract: The travel industry in Hawaii has been experiencing a trend towards more authentic tourism, which reintegrates Hawaiian culture into the visitors’ experience. This study investigated the reintegra- tion of Hawaiian culture into the tourism experience on the Hawaiian Islands by reviewing existing lite- rature, and by analyzing primary data collected through visitor surveys. The purpose of the study was to determine whether there is a visitors’ demand for a more authentic tourism experience in Hawaii through the reintegration of Hawaiian culture, and if so, which efforts should be made or continue to be made to achieve this authenticity. -

America Practices Its Imperial Power

Name: Date: Period: . Directions: Read the history of Hawaii’s annexation and the Queen’s letter to President McKinley before answering the critical thinking questions. America practices its Imperial Power Hawaii was first occupied by both the British and the French before signing a friendship treaty with the United States in 1849 that would protect the islands from European Imperialism. Throughout the 1800s many missionaries and businessmen travel to Hawaii. Protestant missionaries wished to convert the religion of locals and the businessmen are interested in establishing money making sugar plantations. Hawaii was a useful resource to the United States not only because of its rich land, but because of its location as well. The islands are located in a spot that U.S. leaders thought was ideal for a naval port. This base, Pearl Harbor, would give America presence in the Pacific Ocean and create a refueling port for ships in the middle of the ocean. When Queen Liliuokalani took the thrown in 1891 she wanted to limit the power that American business have in Hawaii. America also changed the trading laws, making it extremely expensive for the Hawaiian plantations to export their sugar product back to the mainland. In 1893 these plantation owners, led by Samuel Dole and with the support of the United States Marines revolt against the Queen and forced her into surrendering the thrown. With American businessmen in control, they set up their own government appointing Samuel Dole as governor. With plantation owners in control, it was in their best interest for their business trade to become a part of the United States and they requested to be annexed.