The Heart of the Matter: the Humanities and Social Sciences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seeing (For) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2014 Seeing (for) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance Benjamin Park anderson College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, and the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation anderson, Benjamin Park, "Seeing (for) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance" (2014). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623644. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-t267-zy28 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Seeing (for) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance Benjamin Park Anderson Richmond, Virginia Master of Arts, College of William and Mary, 2005 Bachelor of Arts, Virginia Commonwealth University, 2001 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy American Studies Program College of William and Mary May 2014 APPROVAL PAGE This Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Benjamin Park Anderson Approved by T7 Associate Professor ur Knight, American Studies Program The College -

Cultural Anthropology Through the Lens of Wikipedia: Historical Leader Networks, Gender Bias, and News-Based Sentiment

Cultural Anthropology through the Lens of Wikipedia: Historical Leader Networks, Gender Bias, and News-based Sentiment Peter A. Gloor, Joao Marcos, Patrick M. de Boer, Hauke Fuehres, Wei Lo, Keiichi Nemoto [email protected] MIT Center for Collective Intelligence Abstract In this paper we study the differences in historical World View between Western and Eastern cultures, represented through the English, the Chinese, Japanese, and German Wikipedia. In particular, we analyze the historical networks of the World’s leaders since the beginning of written history, comparing them in the different Wikipedias and assessing cultural chauvinism. We also identify the most influential female leaders of all times in the English, German, Spanish, and Portuguese Wikipedia. As an additional lens into the soul of a culture we compare top terms, sentiment, emotionality, and complexity of the English, Portuguese, Spanish, and German Wikinews. 1 Introduction Over the last ten years the Web has become a mirror of the real world (Gloor et al. 2009). More recently, the Web has also begun to influence the real world: Societal events such as the Arab spring and the Chilean student unrest have drawn a large part of their impetus from the Internet and online social networks. In the meantime, Wikipedia has become one of the top ten Web sites1, occasionally beating daily newspapers in the actuality of most recent news. Be it the resignation of German national soccer team captain Philipp Lahm, or the downing of Malaysian Airlines flight 17 in the Ukraine by a guided missile, the corresponding Wikipedia page is updated as soon as the actual event happened (Becker 2012. -

Civil Wars & Global Disorder

on the horizon: Dædalus Ending Civil Wars: Constraints & Possibilities edited by Karl Eikenberry & Stephen D. Krasner Francis Fukuyama, Tanisha M. Fazal, Stathis N. Kalyvas, Steven Heydemann, Chuck Call & Susanna P. Campbell, Sumit Ganguly, Clare Lockhart, Thomas Risse & Eric Stollenwerk, Tanja A. Börzel & Sonja Grimm, Seyoum Mesfi n & Abdeta Beyene, Lyse Doucet, Nancy Lindborg & Joseph Hewitt, Richard Gowan & Stephen John Stedman, and Jean-Marie Guéhenno & Global Disorder: Threats Opportunities 2017 Civil Wars Fall Dædalus Native Americans & Academia Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences edited by Ned Blackhawk, K. Tsianina Lomawaima, Bryan McKinley Jones Brayboy, Philip J. Deloria, Fall 2017 Loren Ghiglione, Douglas Medin, and Mark Trahant Anti-Corruption: Best Practices edited by Robert I. Rotberg Civil Wars & Global Disorder: Threats & Opportunities Karl Eikenberry & Stephen D. Krasner, guest editors with James D. Fearon Bruce D. Jones & Stephen John Stedman Stewart Patrick · Martha Crenshaw Paul H. Wise & Michele Barry Representing the intellectual community in its breadth Sarah Kenyon Lischer · Vanda Felbab-Brown and diversity, Dædalus explores the frontiers of Hendrik Spruyt · Stephen Biddle · William Reno knowledge and issues of public importance. Aila M. Matanock & Miguel García-Sánchez Barry R. Posen U.S. $15; www.amacad.org; @americanacad Civil War & the Current International System James D. Fearon Abstract: This essay sketches an explanation for the global spread of civil war up to the early 1990s and the partial -

1 Ivy Schweitzer Curriculum Vitae 2018

Ivy Schweitzer Curriculum Vitae 2018 b 24 Hopson Road Norwich, VT 05055 802 649-2947; mobile 603 443-1314 office: 603 646-2930, fax: 603 646-2159 email: [email protected] Education Ph. D. Brandeis University, Waltham, Massachusetts; June, l983, American Literature Dissertation: "Literature as Sacrament: The Evolution of Puritan Sacramentalism and Its Influence on Puritan and Emersonian Aesthetics." Directors: Michael Gilmore and Allen Grossman M.A. English and American Literature, Brandeis University, February, l976 B.A. State University of New York at Buffalo, Buffalo, New York, January l973 in English Literature: Honors in English, summa cum laude, Phi Beta Kappa Study Abroad, Manchester University, Manchester, England, l971-l972, English Literature, Art History and Comparative Religion Academic Employment Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire Professor of English, 2005-present Chair, Women's and Gender Studies Program, 2007-2010 Senior Faculty Associate, East Wheelock Cluster, 2001-2006 Women's and Gender Studies Program, (joint title), 2003-present Co-Chair, Women’s Studies Program, 1992-1994 Associate Professor of English, 1990-2005 Assistant Professor of English, 1983-1990 Visiting Faculty in American Literature, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, Scotland, Fall 2000, Fall 2010, Fall 2013 Visiting Faculty, English and American Literature, University College, London, Fall-Winter, 1990-91 Field Faculty in English, Vermont College Graduate School, l985-l986 Scholar, Advisor and Lecturer, Vermont Council on the Arts, Reading Series, l985-2001 Scholar, Advisor and Lecturer New Hampshire Library Association, Reading Series, l984- 2001 Faculty Supervisor, The Field School, Washington, D.C., 1981-1983 Teacher, English and American Literature (7th, 11th and 12 grades), The Field School, Washington D.C. -

20 Years of Innovative Admissions After the Last Curtain Call

THE OWL THE ALUMNI MAGAZINE OF COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GENERAL STUDIES After the Last Curtain Call: Dancers In Transition Forecasting Success: Remembering 20 Years of Innovative Dean Emeritus Admissions Peter J. Awn 2019-2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS THE OWL LETTER FROM THE DEAN THE ALUMNI MAGAZINE OF COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GENERAL STUDIES Lisa Rosen-Metsch ’90 Dean Curtis Rodgers Vice Dean Jill Galas Hickey Associate Dean for Development and Alumni Relations Aviva Zablocki Director of Alumni Relations 18 14 12 Editor Dear GS Alumni and Friends, Allison Scola IN THIS ISSUE Communications, Special Projects As I reflect upon the heartbreak and challenges we have faced her network in the fashion industry to produce and donate PPE to frontline medical workers, to name just two of our alumni who Feature Story 14 The Transitional Dance since the last printing of The Owl, I am struck by my feelings of Since childhood, most professional dancers sacrificed, showed Contributors pride in how our amazing and resilient GS community has risen have made significant contributions. discipline, and gave themselves over dreams that required laser to meet these moments. When I step back, our school motto, Adrienne Anifant Lux Meanwhile, the accomplishments of members of our community focus on their goals. But what happens when their dream careers —the light shines in the darkness—is taking on Eileen Barroso in Tenebris Lucet extend across industries and causes. Poet Louise Glück, who are closer to the end than the beginning? new meaning. From the tragic loss of our beloved Dean Emeritus Nancy J. Brandwein attended GS in the 1960s, recently was awarded the Nobel Prize Peter J. -

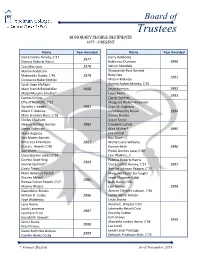

Honorary Degree Recipients 1977 – Present

Board of Trustees HONORARY DEGREE RECIPIENTS 1977 – PRESENT Name Year Awarded Name Year Awarded Claire Collins Harvey, C‘37 Harry Belafonte 1977 Patricia Roberts Harris Katherine Dunham 1990 Toni Morrison 1978 Nelson Mandela Marian Anderson Marguerite Ross Barnett Ruby Dee Mattiwilda Dobbs, C‘46 1979 1991 Constance Baker Motley Miriam Makeba Sarah Sage McAlpin Audrey Forbes Manley, C‘55 Mary French Rockefeller 1980 Jesse Norman 1992 Mabel Murphy Smythe* Louis Rawls 1993 Cardiss Collins Oprah Winfrey Effie O’Neal Ellis, C‘33 Margaret Walker Alexander Dorothy I. Height 1981 Oran W. Eagleson Albert E. Manley Carol Moseley Braun 1994 Mary Brookins Ross, C‘28 Donna Shalala Shirley Chisholm Susan Taylor Eleanor Holmes Norton 1982 Elizabeth Catlett James Robinson Alice Walker* 1995 Maya Angelou Elie Wiesel Etta Moten Barnett Rita Dove Anne Cox Chambers 1983 Myrlie Evers-Williams Grace L. Hewell, C‘40 Damon Keith 1996 Sam Nunn Pinkie Gordon Lane, C‘49 Clara Stanton Jones, C‘34 Levi Watkins, Jr. Coretta Scott King Patricia Roberts Harris 1984 Jeanne Spurlock* Claire Collins Harvey, C’37 1997 Cicely Tyson Bernice Johnson Reagan, C‘70 Mary Hatwood Futrell Margaret Taylor Burroughs Charles Merrill Jewel Plummer Cobb 1985 Romae Turner Powell, C‘47 Ruth Davis, C‘66 Maxine Waters Lani Guinier 1998 Gwendolyn Brooks Alexine Clement Jackson, C‘56 William H. Cosby 1986 Jackie Joyner Kersee Faye Wattleton Louis Stokes Lena Horne Aurelia E. Brazeal, C‘65 Jacob Lawrence Johnnetta Betsch Cole 1987 Leontyne Price Dorothy Cotton Earl Graves Donald M. Stewart 1999 Selma Burke Marcelite Jordan Harris, C‘64 1988 Pearl Primus Lee Lorch Dame Ruth Nita Barrow Jewel Limar Prestage 1989 Camille Hanks Cosby Deborah Prothrow-Stith, C‘75 * Former Student As of November 2019 Board of Trustees HONORARY DEGREE RECIPIENTS 1977 – PRESENT Name Year Awarded Name Year Awarded Max Cleland Herschelle Sullivan Challenor, C’61 Maxine D. -

Sociology One Course in Upper Level Writing

North Dakota State University 1 ENGL 120 College Composition II 3 Sociology One Course in Upper Level Writing. Select one of the following: 3 ENGL 320 Business and Professional Writing Sociology is the scientific study of social structure, social inequality, social ENGL 324 Writing in the Sciences change, and social interaction that comprise societies. The sociological ENGL 358 Writing in the Humanities and Social Sciences perspective examines the broad social context in which people live. This context shapes our beliefs and attitudes and sets guidelines for what we ENGL 459 Researching and Writing Grants and Proposal do. COMM 110 Fundamentals of Public Speaking 3 Quantitative Reasoning (R): The curriculum is structured to introduce majors to the sociology STAT 330 Introductory Statistics 3 discipline and provide them with conceptual and practical tools to understand social behavior and societies. Areas of study include small Science & Technology (S): 10 groups, populations, inequality, diversity, gender, social change, families, A one-credit lab must be taken as a co-requisite with a general community development, organizations, medical sociology, aging, and education science/technology course unless the course includes an the environment. embedded lab experience equivalent to a one-credit course. Select from current general education list. The 38-credit requirement includes the following core: Humanities & Fine Arts (A): Select from current general 6 education list ANTH 111 Introduction to Anthropology 3 Social & Behavioral Sciences -

How Ought We Live?

How Ought We Live? The Ongoing Deconstruction of Our Values Mark Nielsen This thesis is submitted to the School of History and Philosophy at the University of New South Wales in fulfilment of the requirements of the PhD in Philosophy 2010 ii iii Dedication For Theresa and Charlotte. iv Acknowledgements Firstly, I would like to thank my supervisor, Paul Patton, for his generous support in assisting me in the creation of this thesis. I am particularly grateful for his patience and understanding in relation to the research method I have used. I would also like to thank my co-supervisor, Rosalyn Diprose, for her generous support. Finally, I would like to thank my wife, Theresa, for her unwavering support over the years and for reminding me of what is important in life. v Table of Contents Title Page i Thesis/Dissertation Sheet ii Originality Statement, Copyright Statement and Authenticity Statement iii Dedication iv Acknowledgements v Table of Contents vi Introduction: Horizontal Philosophy and the Construction of an Ethical Rhizome 1 Macro-Sociological Plateaus 1. The Salesman as Values Educator: A Lesson From a Primary School Teacher 25 2. Feeling Unhappy and Overweight: Overconsumption and the Escalation of Desire 38 3. The Politics of Greed: Trivial Domestic Democracy 52 Philosophical Plateaus 4. The Democratic Rise of the Problem of ―How Ought We Live?‖ 67 5. Living in the Land of Moriah: The Problem of ―How Ought We Sacrifice?‖ 80 6. Welcome to the Mobile Emergency Room: A Convergence Between Ethics and Triage 101 7. Diagnostic Trans-Evaluation and the Creation of New Priorities 111 8. -

HD in 2020: Peacemaking in Perspective → Page 10 About HD → Page 6 HD Governance: the Board → Page 30

June 2021 EN About HD in 2020: HD governance: HD → page 6 Peacemaking in perspective → page 10 The Board → page 30 Annual Report 2020 mediation for peace www.hdcentre.org Trusted. Neutral. Independent. Connected. Effective. The Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue (HD) mediates between governments, non-state armed groups and opposition parties to reduce conflict, limit the human suffering caused by war and develop opportunities for peaceful settlements. As a non-profit based in Switzerland, HD helps to build the path to stability and development for people, communities and countries through more than 50 peacemaking projects around the world. → Table of contents HD in 2020: Peacemaking in perspective → page 10 COVID in conflict zones → page 12 Social media and cyberspace → page 12 Supporting peace and inclusion → page 14 Middle East and North Africa → page 18 Francophone Africa → page 20 The Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue (HD) is a private diplomacy organisation founded on the principles of humanity, Anglophone and Lusophone Africa → page 22 impartiality, neutrality and independence. Its mission is to help prevent, mitigate and resolve armed conflict through dialogue and mediation. Eurasia → page 24 Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue (HD) Asia → page 26 114 rue de Lausanne, 1202 – Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 (0)22 908 11 30 Email: [email protected] Latin America → page 28 Website: www.hdcentre.org Follow HD on Twitter and Linkedin: https://twitter.com/hdcentre https://www.linkedin.com/company/centreforhumanitariandialogue Design and layout: Hafenkrone © 2021 – Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue About HD governance: Investing Reproduction of all or part of this publication may be authorised only with written consent or acknowledgement of the source. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Debra M. Satz ACADEMIC POSITIONS: Senior Associate Dean for the Humanities and Arts, Stanford University, 2010

CURRICULUM VITAE Debra M. Satz Department of Philosophy [email protected] Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-2155 (650) 723-2133; (650) 723-0985 (fax) ACADEMIC POSITIONS: Senior Associate Dean for the Humanities and Arts, Stanford University, 2010- Marta Sutton Weeks Professor of Ethics in Society, Stanford University, 2007-present Professor of Philosophy, Stanford University, 2007-present Faculty Director, Bowen H. McCoy Family Center for Ethics in Society, 2008-present Professor, by courtesy, of Political Science, Stanford University, 2007-present Affiliated with: *Center for Social Innovation, Graduate School of Business *Haas Center for Public Service *Center for Comparative Studies in Race and Ethnicity *John Gardner Center for Youth and Their Communities *Center for the Study of Poverty and Inequality *Interdisciplinary Program in Environment and Resources *Public Policy Program Philosophy Department Chair (interim) 2004-2005 Marshall Weinberg Distinguished Visiting Professor, University of Michigan, Fall 2002. Associate Professor, Department of Philosophy, Stanford University, 1996-2007 Associate Professor, by courtesy, Department of Political Science, 1996-2007 Director, Program in Ethics in Society, 1996-2007 Assistant Professor, Department of Philosophy, Stanford University, 1988-1996 Assistant Professor, by courtesy, Department of Political Science, 1988-1996 Assistant Professor, Department of Philosophy, Swarthmore College, 1987-88 Lecturer, Program in Social Studies, Harvard University, 1986-87 EDUCATION: 1987 Massachusetts -

Business Leader Economic Development for the Regions of Los Angeles County Los Angeles County Economic Development Corporation Spring/Summer 2005

Business Leader Economic Development for the Regions of Los Angeles County www.laedc.org Los Angeles County Economic Development Corporation Spring/Summer 2005 In This Issue: LAEDC REACHES 100,000 JOBS MILESTONE Business Assistance Program Sets a New Standard for Years to Come á President’s Annual Report 2004-2005 A testament to LAEDC’s mission to “attract, retain and grow á Story and photos from businesses and jobs in the re- the 9th Annual Eddy gions of LA County,” LAEDC Awards celebrates its new milestone of having attracted and retained á LAEDC/WTCA 2004 100,532 jobs from 1996 to Asia Mission Report April 2005. Those jobs trans- late to $3.5 billion in annual á Membership News and economic impact from salaries Updates and $65 million in annual tax revenue benefit to Los Angeles á And much more! County. At the May 19 Membership Meeting, Los Angeles County Supervisor Michael Antonovich presented the LAEDC with a special commendation from the County Supervisors for this im- portant achievement. Standing from left to right: Westside Regional Manager (RM) Libby Wil- liams, Former RM Judy Turner, San Fernando Valley RM Alex Rosas, Business Development Coordinator Bob Machuca, Former RM Saul Rodney F. Banks, Chairman of Gomez, Gateway Cities RM Barbara Levine, LAEDC Vice President Busi- the Board of the LAEDC said, ness Development Greg Whitney, Former RM Elaine Cullen, Undersecre- “We are pleased to have tary Business, Transportation & Housing Barry Sedlik, Former RM David reached this milestone in job Myers, Antelope & Santa Clarita Valleys RM Henry Leyva, Metro & South creation and retention. -

Biohumanities: Rethinking the Relationship Between Biosciences, Philosophy and History of Science, and Society*

Biohumanities: Rethinking the relationship between biosciences, philosophy and history of science, and society* Karola Stotz† Paul E. Griffiths‡ ____________________________________________________________________ †Karola Stotz, Cognitive Science Program, 810 Eigenmann, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN 47408, USA, [email protected] ‡Paul Griffiths, School of Philosophical and Historical Inquiry, University of Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia, [email protected] *This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grants #0217567 and #0323496. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. Griffiths work on the paper was supported by Australian Research Council Federation Fellowship FF0457917. Abstract We argue that philosophical and historical research can constitute a ‘Biohumanities’ which deepens our understanding of biology itself; engages in constructive 'science criticism'; helps formulate new 'visions of biology'; and facilitates 'critical science communication'. We illustrate these ideas with two recent 'experimental philosophy' studies of the concept of the gene and of the concept of innateness conducted by ourselves and collaborators. 1 1. Introduction: What is 'Biohumanities'? Biohumanities is a view of the relationship between the humanities (especially philosophy and history of science), biology, and society1. In this vision, the humanities not only comment on the significance or implications of biological knowledge, but add to our understanding of biology itself. The history of genetics and philosophical work on the concept of the gene both enrich our understanding of genetics. This is perhaps most evident in classic works on the history of genetics, which not only describe how we reached our current theories but deepen our understanding of those theories through comparing and contrasting them to the alternatives which they displaced (Olby, 1974, 1985).