Wisconsin's Nonpoint Source Program Management Plan FFY 2016-2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Role of Geosynthetics in Erosion and Sediment Control: an Overview

Geotextiles and Geomembranes I I (1992) 535-550 The Role of Geosynthetics in Erosion and Sediment Control: An Overview M. S. Theisen Erosion Control Materials, Synthetic Industries, Construction Products Division, 4019 Industry Drive, Chattanooga, Tennessee 37416, USA ABSTRACT The use ofgeosynthetic erosion and sediment materials continues to expand at a rapid pace. From their early beginnings in the late 1950s, geosynthetic materials today are the backbone of the erosion and sediment control industry. Geosynthetic components are an integral part of erosion and sediment materials ranging from temporary products such as hydraulic mulch geofibers, plastic erosion control meshes and nettings, erosion control blankets and silt fences to high performance turf reinforcement mats, geocellular confinement systems, erosion control geotextiles andfabric formed revetments. This paper provides a brief overview of these materials and concepts. INTRODUCTION Hopefully we are entering a new environmental era where concern for the protection of our planet's natural resources will reach global proportions. Continued technological advances have led to improved monitoring of Earth's vital signs. As such, prior theoretical modeling of environmental concerns such as the greenhouse effect, ozone depletion, rising sea levels, deforestation, drought, accelerated erosion, sediment loading of waterways, species extinction and the eventual downfall of mankind appear chillingly realistic. 535 536 M. S. Theisen Slogans such as 'Think globally, act locally', 'Love your mother' and 'Someone always lives downstream' are spearheading the efforts of numerous preservation groups. With the continued demise of oppressive governments, optimism for world peace and an unprecedented feeling of global unity, a spirit of environmental cooperation is beginning to prevail. -

Audubon Bend Gravel Road Repair Gavins Point Dam, SD

SPECIFICATIONS & DRAWINGS (Purchase Order - For Construction Contract) Solicitation Number W9128F21Q0018 ____________________________________________________________ Audubon Bend Gravel Road Repair Gavins Point Dam, SD March 2021 US Army Corps of Engineers Omaha District This page was intentionally left blank for duplex printing. AUDUBON BEND GRAVEL ROAD REPAIR GAVINS POINT DAM, SD PROJECT TABLE OF CONTENTS DIVISION 00 - PROCUREMENT AND CONTRACTING REQUIREMENTS 00 10 00-3 PRICING SCHEDULE STATEMENT OF WORK 00 73 00 SUPPLEMENTARY CONDITIONS (SPECIAL CONTRACT REQUIREMENTS)FOR PURCHASE ORDERS DIVISION 01 - GENERAL REQUIREMENTS 01 22 00 MEASUREMENT AND PAYMENT 01 33 00 SUBMITTAL PROCEDURES 01 41 26.02 24 (NEBRASKA) NPDES PERMIT REQUIREMENTS FOR STORM WATER DISCHARGES FROM CONSTRUCTION SITES 01 57 20.00 10 ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION 01 57 23 TEMPORARY STORM WATER POLLUTION CONTROL DRAWINGS -- End of Project Table of Contents -- Page 1 This page was intentionally left blank for duplex printing. Audubon Bend Gravel Road Repairs, Gavins Point Dam, NE GP82 SECTION 00 10 00 PRICING SCHEDULE CLIN DESCRIPTION QTY UNIT UNIT PRICE AMOUNT BASE ITEMS 0001 Mobilization and Demobilization 1 JOB XXX $_______________ Blade entire length of road surface prior to placing gravel to smooth out 0002 1 JOB XXX $_______________ scour holes, rebuild crown. Includes areas over culverts. – 4,750 FEET Reset existing 24’’ CMP with flared 0003 ends to properly drain to North East – 1 JOB XXX $_______________ 1 EACH. Install new USACE provided 48’’ 0004 culvert with flared end (includes trees’ 1 JOB XXX $_______________ removal as necessary) – 1 EACH. Reconstruct approximately 270’ of 0005 eroded road at the existing culvert 720 CY $_______________ $_______________ (includes sodding and seeding). -

The Evolution of Geosynthetics in Erosion and Sediment Control

Presented at GRI-25, Geosynthetics Research Institute, Long Beach, CA, 2013 THE EVOLUTION OF GEOSYNTHETICS IN EROSION AND SEDIMENT CONTROL C. Joel Sprague TRI/Environmental, Inc., Greenville, SC ABSTRACT Much of the development of geosynthetics technology in environmental applications has been in response to government regulations. This is certainly true for geosynthetics used in erosion and sediment control. Geosynthetics continue to replace traditional materials such as soil and stone in performing important engineering functions in erosion and sediment control applications while simultaneously introducing greater versatility and cost-effectiveness. Geosynthetics are widely used as a “carrier” for degradable materials to the enhancement of vegetative establishment; as nondegradable materials to extend the erosion control limits of vegetation or soil; as primary slope or channel linings; as components in silt fences and turbidity curtains; and as a component in an ever growing array of sediment retention devices. Along with the introduction of geosynthetics into this wide range of applications has come the need for industry-wide initiatives to promote their correct use and new test methods to characterize them. All of which, are a “work in progress”. THE NEED FOR EROSION AND SEDIMENT CONTROLS Much of the development of geosynthetics technology related to erosion and sediment control applications has been in response to government regulations. A progression of regulatory actions has brought a national focus on erosion and sediment control, including: Amendments to the Federal Water Pollution Control Act (1985) - eliminating discharge of any pollutant to navigable waters. The Clean Water Act (1987) - requiring National Pollution Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) Permits for large construction sites. -

Erosion and Sediment Control Plan Checklist

Erosion Prevention and Sediment Control Plan Checklist Page 1 of 4 What is an Erosion Prevention and Sediment Control Plan? Erosion and sediment control is much more than silt fence and hay bales. Prior to developing an Erosion Prevention and Sediment Control Plan (EPSCP), it is important to have minimized the areas of disturbed soils and the duration of exposure. It is also imperative to control water at up- slope site perimeters, control water on-site, control sediment on-site, and control sediment at the downslope site perimeters. An EPSCP is the final element in the erosion and sediment control planning process and a necessary component of an Act 250 permit application. The EPSCP ensures that sediment transport is addressed in one of the most crucial stages of the project: the planning stage. A good erosion prevention and sediment control plan first minimizes the extent of disturbance by focusing on erosion control (minimizing disturbed areas, seeding, mulching, matting) by controlling the amount of soil that can run off and by stabilizing exposed soil. Sediment control measures (i.e. stabilized construction entrances) then focus on any sediment that has escaped your erosion control measures. Erosion prevention measures are far more effective than sediment control measures (such as silt fence) and should be the primary focus of any EPSCP. An EPSCP has five primary components: 1. Location map (USGS and other) 2. Existing conditions site plan 3. Grading plan and construction timetable 4. Erosion prevention and sediment control site plan and timetable 5. Narrative briefly describing the four plans The location map shows the proximity of the site to any surface water bodies, roads, etc. -

Stormwater Management and Sediment and Erosion Control Plan Review Checklist for Design Professionals

Stormwater Management and Sediment and Erosion Control Plan Review Checklist For Design Professionals This Plan Review Checklist for Design Professionals has been developed to aid those who prepare Stormwater Pollution Prevention Plans (SWPPPs). Adjacent to the heading for most sections are references from the corresponding portion of the NPDES General Permit for Stormwater Discharges from Construction Activities (SCR100000), which was issued on October 15, 2012. SWPPP Preparers should not utilize this checklist as a substitute for the language in the permit and should review the permit itself for more information on each specific requirement. The permit may be found at: http://www.scdhec.gov/environment/water/swater/docs/CGP-permit.pdf In the space provided please indicate the location and page number(s) where each item below can be found in your SWPPP or supporting calculations. If an item is not applicable, put N/A. The Department reserves the right to modify this checklist at any time. The Coastal Zone consists of the following counties: Beaufort, Berkeley, Charleston, Colleton, Dorchester, Georgetown, Horry, and Jasper. *Revised Items in Red Project Information: Project Name: County: Checklist Completed by: Printed name: ___________________________ Signature: ___________________________ Date:___________ PLANS AND MAPS 1. CURRENT COMPLETED APPLICATION FORM ● Original Signature of individual with signatory authority for the applicant according to requirements set forth in R.61-9.122.22 (see Appendix C) ● All items completed and answered -

Soil Erosion and Sediment Control Field Handbook

Erosion and Sediment Control Field Handbook September 2017 This page intentionally left blank. Chapter 2 – Soil Stabilization Stabilized Construction Entrance 9 Table of Contents Table Stabilized Construction Entrance with Wash Rack 11 Rolled Erosion Control Products – Slope 13 Rolled Erosion Control Products – Channel 14 Vegetative Stabilization N/A 16 Polyacrylamides N/A 20 Chapter 3 – Sediment Barriers and Filters Silt Fence 23 Chapter 3 – Sediment Barriers and Filters Super Silt Fence 26 Filter Sock 29 Straw Bale Dike 32 Standard Inlet Protection 34 At Grade Inlet Protection 36 Table of Contents Table Curb Inlet Protection 37 Standard Inlet Guard 39 Chapter 3 – Sediment Barriers and Filters Stone Check Dam 41 Table of Contents Table Silt Fence on Pavement 43 Chapter 4 – Conveyance Diversion Fence 45 Dike/Swale 47 Earth Dike 49 Temporary Swales 53 Chapter 5 – Water Control Rock Outlet Protection 55 Chapter 6 – Sediment Traps and Basins Sediment Traps 59 Sediment Basins N/A 64 Chapter 7 – Dewatering Table of Contents Table Removable Pumping Station 73 Sump Pit 75 Chapter 7 – Dewatering Portable Sediment Tank 76 Table of Contents Table Pumped Water Filter Bag 78 Chapter 9 – Other Practices Dust Control N/A 79 On-Site Concrete Washout Structure 80 Tree Protection and Preservation 83 This page intentionally left blank. Stabilized Construction Construction Entrance Stabilized 9 Construction Specifications 1. Place the stabilized construction entrance in accordance with the approved plan. Vehicles must travel over the entire length of the SCE. Use a minimum length of 50 feet (30 feet for single-family residence lot) and a minimum width of 10 feet. -

Inspiring Action for Nonpoint Source Pollution Control

A MANUAL FOR WATER RESOURCE PROTECTION Inspiring Action for Nonpoint Source Pollution Control Paul Nelson Scott County, Minnesota Mae A. Davenport Center for Changing Landscapes, University of Minnesota Troy Kuphal Scott Soil and Water Conservation District, Minnesota Inspiring Action for Nonpoint Source Pollution Control: A Manual for Water Resource Protection by Paul Nelson Scott County, Minnesota Mae A. Davenport Center for Changing Landscapes, University of Minnesota Troy Kuphal Scott Soil and Water Conservation District, Minnesota Published by Freshwater Society Saint Paul, Minnesota Acknowledgments Paul Nelson and Troy Kuphal We wish to acknowledge the support of our respective boards — the Scott County Board of Commissioners and the Scott Soil and Water Conservation District Board of Supervisors — and thank them for their will- ingness to let us think and experiment a bit outside the box. We also wish to thank the Scott Watershed Management Organization Watershed Planning Commission members for their support and ongoing advice. In addition, we want to recognize the incredibly talented staff from our two organizations. Their dedication to conservation, building relationships, and delivering excellent service are critical to achieving the accom- plishments detailed in this manual. Their willingness to take, improve, and act on our ideas is inspiring and instrumental to learning and continuous improvement. We also thank our friends at the Board of Soil and Water Resources, the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency, the Metropolitan Council, the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, and the Natural Resource Conservation Service for their support in terms of grants, programs, and technical support. Lastly, and most important, we wish to acknowledge the tremendous conservation ethic exhibited by resi- dents in Scott County. -

Sediment Control Measures

Sediment Control Measures Treat the Problem! Storm Drain Inlet Protection Measures Water Body Protection Measures Down-Slope Protection Measures Stabilized Construction Vehicle Access & Exit Points Dust Generation & Track-Out from Vehicles Soil Stockpiles Non-Storm Water Discharges Sediment Basins Storm Drain Inlet Protection Measures Install appropriate protection measures to minimize the discharge of sediment prior to entry into the inlet Inlet Protection vs. Plow Destruction Habitat Protection? Where’s the Best in this management practice? This is No Place for Sediment to Collect - $$$$$$ What’s in this Storm System? Who’s Cleaning it Out? Protect Inlets Until Final Site Stabilization is Completed! Bylaw 2006 No. 16138 Install and maintain filter fabric bags inside any catch basins, lawn basins, exposed manholes or any other storm sewer access point collecting runoff from the site. Inlet Protection Catch Basin Inserts Maintenance Issues Will Traffic Destroy Your Efforts? Midtown Anchorage Will Your Efforts Destroy Traffic ? Photo Courtesy David Jenkins Storm Drain Inlet Protection • Keeps coarse sediment out of drainage systems • Above ground methods: silt fence, Exert, Dandy Bag • Below ground: catch basin filter BMP WA C-220 OR SC-8 AK - 19 Water Body Protection Measures Install appropriate protection measures to minimize the discharge of sediment prior to entry into the water body. For water bodies located on site or immediately downstream of the site. Tok Turbidity Curtain / Oil Boom • Where intrusion into a watercourse is necessary • Tidal and non-tidal uses • Maximum flow velocity of 5 feet per second • Locate parallel to flow, not across a channel Kotzebue BMP OR RC-10 Columbia River Tidal Influences make maintenance difficult Turbidity / Silt Curtain Ketchikan Down Slope Sediment Controls Gakona Establish and use down-slope sediment controls where storm water will be discharged from disturbed areas of the site. -

Guide to Erosion Prevention and Sediment Control During Construction Activities Polk County, Oregon

Guide to Erosion Prevention and Sediment Control During Construction Activities Polk County, Oregon (Updated May 2009) ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Contents 1. Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………... 1 2. Recommended Erosion Prevention and Sediment Control Measures……….…………………. 1 2.1. Gravel Construction Entrances………………………………………………………… 2 2.2. Temporary Sediment Fences………………………………………………………….. 5 2.3. Straw Bale Sediment Barrier/Bio-Filter Bags………………………………………... 7 2.4. Undisturbed Vegetative Buffers……………………………………………………... 12 2.5. Temporary Grasses and Permanent Vegetative Cover……………………………….. 12 2.6. Straw Mulch………………………………………………………………………….. 12 2.7. Erosion and Matting Blankets………………………………………………………… 14 2.8. Plastic Sheet Covering……………………………………………………………….. 15 2.9. Storm Drain Inlet Protection…………………………………………………………. 16 3. Post Construction Best Management Practices………………………………………………… 20 4. Contact Information ……………………………………………………………………………20 Erosion Prevention and Sediment Control Polk County, OR 1.0 Introduction This brochure contains erosion prevention techniques and sediment control measures as guidance for construction operators. The focus of this brochure is to first, promote erosion prevention techniques, and second, to promote sediment control measures. Erosion prevention techniques are designed to protect soil particles from the force of rain and wind so that they will not erode. These techniques include such things as ground cover and -

Temporary & Permanent Erosion & Sediment Control Measure

Module 3: Temporary Erosion & Sediment Control Measures – NDDOT Erosion & Sediment Control – Construction Course NDDOT Erosion & Sediment Control – Construction Course Module 3: Temporary & Permanent Erosion & Sediment Control Measures 1 What’s covered in this module? 1. Definition of temporary erosion and sediment control 2. Physical erosion and sediment control measures 3. Operational erosion and sediment control measures 4. Dewatering and pumping 2 Page 1 Module 3: Temporary Erosion & Sediment Control Measures – NDDOT Erosion & Sediment Control – Construction Course What are the module’s learning objectives? 1. Explain the difference between temporary and permanent erosion and sediment control in the Special Provisions 2. Identify temporary and permanent erosion and sediment control measures and their appropriate applications 3. Evaluate requirements that influence the installation, maintenance, inspection, and removal of erosion and sediment control measures 3 Construction ESC Temporary vs. Permanent What does temporary vs. permanent mean in the Special Provision? What is temporary erosion control? What is temporary sediment control? Are the two mutually exclusive terms? 4 Page 2 Module 3: Temporary Erosion & Sediment Control Measures – NDDOT Erosion & Sediment Control – Construction Course Construction ESC Key Considerations: Installation (constructability) Maintenance QA/QC Inspection Removal 5 Construction ESC Site visits are needed to properly plan the project Critical areas Does the ESC design match what is needed in the -

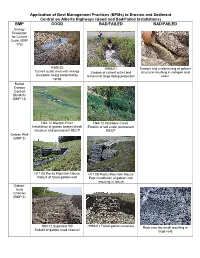

Best Management Practices to Erosion and Sediment Control On

Application of Best Management Practices (BPMs) to Erosion and Sediment Control on Alberta Highways (Good and Bad/Failed Installations) BMP GOOD BAD/FAILED BAD/FAILED Energy Dissipator for Culvert Outlet (BMP 17a) H595:02 H986:01 Erosion and undermining of gabion Culvert outlet area with energy Erosion of culvert outlet and structure resulting in collapse and dissipator being protected by removal of large riprap protection scour riprap Rolled Erosion Control Blankets (BMP 13) H43:12 Iosegun River H43:12 Chicadee Creek Installation of gabion basket check Erosion of soil under permanent structure and permanent RECP RECP Gabion Wall (BMP 2) H11:08 Rocky Mountain House H11:08 Rocky Mountain House Rebuilt of failed gabion wall Poor installation of gabion wall resulting in failure Gabion- lined Channel (BMP 2) H63:12 Supertest Hill H986:01 Failed gabion structure Rock size too small resulting in Rebuilt of gabion-lined channel large void Application of Best Management Practices (BPMs) to Erosion and Sediment Control on Alberta Highways (Good and Bad/Failed Installations) BMP GOOD BAD/FAILED BAD/FAILED Slope Tracking (BMP 34) Track-walk up and down slope – H43:10 strongly recommended Slope tracking along slope – not recommended Silt Fence (BMP 1) H43:10 Formation of gullies below silt “Smile” shape fence Silt Fence (BMP 1) “J” hook Silt needs to be removed H43:12 Silt fence not intercepting flow – need repair Rolled Erosion Control Blankets (BMP 13) H16/H21 Interchange Improper blanket installation Installation of straw RECP in ditch Application -

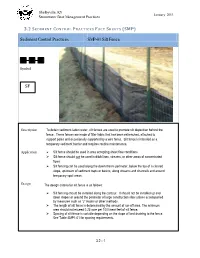

Sediment Control Practices SMP-01 Silt Fence SF

Shelbyville, KY January 2013 Stormwater Best Management Practices 3.2 SEDIMENT CONTROL PRACTICES FACT SHEETS (SMP) Sediment Control Practices SMP-01 Silt Fence Symbol SF Description To detain sediment-laden water, silt fences are used to promote silt deposition behind the fence. These fences are made of filter fabric that has been entrenched, attached to support poles and occasionally supported by a wire fence. Silt fence is intended as a temporary sediment barrier and requires routine maintenance. Application Silt fence should be used in area accepting sheet flow conditions. Silt fence should not be used in ditch lines, streams, or other areas of concentrated flows. Silt fencing can be used along the downstream perimeter, below the toe of a cleared slope, upstream of sediment traps or basins, along streams and channels and around temporary spoil areas. Design The design criteria for silt fence is as follows: Silt fencing should be installed along the contour. It should not be installed up and down slopes or around the perimeter of large construction sites unless accompanied by measures such as “J” Hooks or other methods. The length of silt fence is determined by the amount of run-off area. The minimum area should not exceed 0.25 acre per 100 linear feet of silt fence. Spacing of silt fence is variable depending on the slope of land draining to the fence. See Table SMP1-01 for spacing requirements. 3.2 - 1 Shelbyville, KY January 2013 Stormwater Best Management Practices Design Silt fencing must be installed only where water can pond. Specify silt fencing downgradient from bare soil areas with the ends turned up to prevent bypassing.