Jewish Children: Between Protectors and Murderers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE POLISH POLICE Collaboration in the Holocaust

THE POLISH POLICE Collaboration in the Holocaust Jan Grabowski The Polish Police Collaboration in the Holocaust Jan Grabowski INA LEVINE ANNUAL LECTURE NOVEMBER 17, 2016 The assertions, opinions, and conclusions in this occasional paper are those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect those of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. First printing, April 2017 Copyright © 2017 by Jan Grabowski THE INA LEVINE ANNUAL LECTURE, endowed by the William S. and Ina Levine Foundation of Phoenix, Arizona, enables the Center to bring a distinguished scholar to the Museum each year to conduct innovative research on the Holocaust and to disseminate this work to the American public. Wrong Memory Codes? The Polish “Blue” Police and Collaboration in the Holocaust In 2016, seventy-one years after the end of World War II, the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs disseminated a long list of “wrong memory codes” (błędne kody pamięci), or expressions that “falsify the role of Poland during World War II” and that are to be reported to the nearest Polish diplomat for further action. Sadly—and not by chance—the list elaborated by the enterprising humanists at the Polish Foreign Ministry includes for the most part expressions linked to the Holocaust. On the long list of these “wrong memory codes,” which they aspire to expunge from historical narrative, one finds, among others: “Polish genocide,” “Polish war crimes,” “Polish mass murders,” “Polish internment camps,” “Polish work camps,” and—most important for the purposes of this text—“Polish participation in the Holocaust.” The issue of “wrong memory codes” will from time to time reappear in this study. -

Und Nach Dem Holocaust?

Lea Wohl von Haselberg Und nach dem Holocaust? Jüdische Spielfilmfiguren im (west-)deutschen Film und Fernsehen nach 1945 Neofelis Verlag Die Drucklegung wurde ermöglicht durch die Axel Springer Stiftung, die Ursula Lachnit-Fixson Stiftung und die Ephraim Veitel Stiftung. Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. © 2016 Neofelis Verlag GmbH, Berlin www.neofelis-verlag.de Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Umschlaggestaltung: Marija Skara unter Verwendung von Filmstills aus Zeugin aus der Hölle (Artur Brauner-Archiv im Deutschen Filminstitut – DIF e. V., Frankfurt am Main), Lore (Rohfilm GmbH, Berlin) und Alles auf Zucker! (© Alles auf Zucker! X VERLEIH AG). Lektorat & Satz: Neofelis Verlag (mn/ae) Druck: PRESSEL Digitaler Produktionsdruck, Remshalden Gedruckt auf FSC-zertifiziertem Papier. ISBN (Print): 978-3-943414-60-8 ISBN (PDF): 978-3-943414-81-3 Inhalt Dank ․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․ 11 Einleitung ․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․ 13 I. Jüdische Filmfiguren ․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․ 37 1. Realistische jüdische Figuren ․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․42 2. Stereotype und die Darstellung jüdischer Filmfiguren ․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․ 47 2.1 Figurenstereotype ․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․ 47 2.2 Stereotype als Bilder des Anderen ․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․․ 51 2.3 -

Making Defiance Where He Built a Trucking Business with His Wife Lilka, (Played in the Film by Alexa Davalos)

24 | Lexington’s Colonial Times Magazine MARCH | APRIL 2009 a book, and a book is not a movie. So it has to be different. I cannot put everything that comes from years of work into two hours.’” “Did you actually talk to Tuvia?” prompted Leon Tec. His wife introduced him to the audience as “The troublemaker, my husband.” After the war Tuvia Bielski moved first to Israel and then to New York, Making Defiance where he built a trucking business with his wife Lilka, (played in the film by Alexa Davalos). Nechama Tec had spoken with him by telephone while researching her book “In the Lion’s Den,” but all attempts to meet in person had been stymied by Lilka Bielski’s excuses. Finally, Tec secured a meeting at the Bielskis’ Brooklyn home in May 1987. She hired a driver for the two-hour drive from Westport, Conn., and was greeted by Lilka, who told her that Tuvia had had a bad night, was very sick, and could not see her as planned. Tec said that she was leaving for Israel the next day on a research trip, and was politely insistent. “I want to get a sense of the man before I go,” she told Lilka. “So we’re going back and forth on the doorstep and she doesn’t let me in, and we hear a voice from the other room, ‘Let her in,’” recalled Tec. Tuvia Bielski, clearly weak and very sick, came out to meet her, dismissed the hovering Lilka, and sat down with Tec and her tape recorder. -

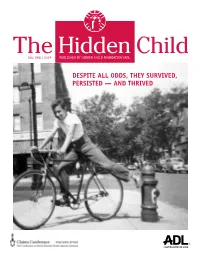

Despite All Odds, They Survived, Persisted — and Thrived Despite All Odds, They Survived, Persisted — and Thrived

The Hidden® Child VOL. XXVII 2019 PUBLISHED BY HIDDEN CHILD FOUNDATION /ADL DESPITE ALL ODDS, THEY SURVIVED, PERSISTED — AND THRIVED DESPITE ALL ODDS, THEY SURVIVED, PERSISTED — AND THRIVED FROM HUNTED ESCAPEE TO FEARFUL REFUGEE: POLAND, 1935-1946 Anna Rabkin hen the mass slaughter of Jews ended, the remnants’ sole desire was to go 3 back to ‘normalcy.’ Children yearned for the return of their parents and their previous family life. For most child survivors, this wasn’t to be. As WEva Fogelman says, “Liberation was not an exhilarating moment. To learn that one is all alone in the world is to move from one nightmarish world to another.” A MISCHLING’S STORY Anna Rabkin writes, “After years of living with fear and deprivation, what did I imagine Maren Friedman peace would bring? Foremost, I hoped it would mean the end of hunger and a return to 9 school. Although I clutched at the hope that our parents would return, the fatalistic per- son I had become knew deep down it was improbable.” Maren Friedman, a mischling who lived openly with her sister and Jewish mother in wartime Germany states, “My father, who had been captured by the Russians and been a prisoner of war in Siberia, MY LIFE returned to Kiel in 1949. I had yearned for his return and had the fantasy that now that Rivka Pardes Bimbaum the war was over and he was home, all would be well. That was not the way it turned out.” Rebecca Birnbaum had both her parents by war’s end. She was able to return to 12 school one month after the liberation of Brussels, and to this day, she considers herself among the luckiest of all hidden children. -

Szymon Datner German Nazi Crimes Against Jews Who

JEWISH HISTORICAL INSTITUTE BULLETIN NO. 75 (1970) SZYMON DATNER GERMAN NAZI CRIMES AGAINST JEWS WHO ESCAPED FROM THE GHETTOES “LEGAL” THREATS AND ORDINANCES REGARDING JEWS AND THE POLES WHO HELPED THEM Among other things, the “final solution of the Jewish question” required that Jews be prohibited from leaving the ghettoes they were living in—which typically were fenced off and under guard. The occupation authorities issued inhumane ordinances to that effect. In his ordinance of October 15, 1941, Hans Frank imposed draconian penalties on Jews who escaped from the ghettoes and on Poles who would help them escape or give them shelter: “§ 4b (1) Jews who leave their designated quarter without authorisation shall be punished by death. The same penalty shall apply to persons who knowingly shelter such Jews. (2) Those who instigate and aid and abet shall be punished with the same penalty as the perpetrator; acts attempted shall be punished as acts committed. A penalty of severe prison sentence or prison sentence may be imposed for minor offences. (3) Sentences shall be passed by special courts.” 1 In the reality of the General Government (GG), § 4b (3) was never applied to runaway Jews. They would be killed on capture or escorted to the nearest police, gendarmerie, Gestapo or Kripo station and, after being identified as Jews and tortured to give away those who helped or sheltered them, summarily executed. Many times the same fate befell Poles, too, particularly those living in remote settlements and woodlands. The cases of Poles who helped Jews, which were examined by special courts, raised doubts even among the judges of this infamous institution because the only penalty stipulated by law (death) was so draconian. -

JUL 29 Poland Between the Wars BARBARA KIRSHENBLATT-GIMBLETT | Delivered in English

MONDAY Coming of Age: Jewish Youth in JUL 29 Poland between the Wars BARBARA KIRSHENBLATT-GIMBLETT | Delivered in English During the 1930s, the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research organized three competitions for youth autobiographies. These extraordinary documents – more than 600 of them were submitted – are unique testimony to the hopes and dreams, as well as to the reality of those who were growing up in Poland at the time. Mayer Kirshenblatt, who was born in Opatów (Yiddish: Apt) in 1916, could well have been one of those autobiographers. Although he did not enter the competition, he did recall his youth much later during interviews recorded by his daughter during the last forty years of his life. This illustrated lecture will relate the youth autobiographies written in real time, by youth who had no idea of what the future would hold, with Mayer’s recollections in words and paintings many years later. The talk will include a short film about Mayer’s return to his hometown and how he was received by those living there today. Finally, the talk will consider the role of the youth autobiographies and Mayer’s childhood memories in POLIN Museum’s Core Exhibition. Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett is Chief Curator of the Core Exhibition at POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews and University Professor Emerita and Professor Emerita of Performance Studies at New York University. Her books include Destination Culture: Tourism, Museums, and Heritage; Image before My Eyes: A Photographic History of Jewish Life in Poland, 1864–1939 (with Lucjan Dobroszycki); and They Called Me Mayer July: Painted Memories of a Jewish Childhood in Poland Before the Holocaust (with Mayer Kirshenblatt). -

Gazeta Spring 2019 Roman Vishniac (1897-1990) Albert Einstein in His Office, Princeton University, New Jersey, 1942

Volume 26, No. 1 Gazeta Spring 2019 Roman Vishniac (1897-1990) Albert Einstein in his office, Princeton University, New Jersey, 1942. Gelatin Silver print. The Magnes Collection of Jewish Art and Life, University of California, Berkeley, gift of Mara Vishniac Kohn, 2016.6.10. A quarterly publication of the American Association for Polish-Jewish Studies and Taube Foundation for Jewish Life & Culture Editorial & Design: Tressa Berman, Fay Bussgang, Julian Bussgang, Shana Penn, Antony Polonsky, Adam Schorin, Maayan Stanton, Agnieszka Ilwicka, William Zeisel, LaserCom Design. CONTENTS Message from Irene Pipes ............................................................................................... 2 Message from Tad Taube and Shana Penn ................................................................... 3 FEATURES The Road to September 1939 Jehuda Reinharz and Yaacov Shavit ........................................................................................ 4 Honoring the Memory of Paweł Adamowicz Antony Polonsky .................................................................................................................... 8 Roman Vishniac Archive Gifted to Magnes Collection of Jewish Art and Life Francesco Spagnolo ............................................................................................................ 11 Keeping Jewish Memory Alive in Poland Leora Tec ............................................................................................................................ 15 The Untorn Life of Yaakov -

Jewish Behavior During the Holocaust

VICTIMS’ POLITICS: JEWISH BEHAVIOR DURING THE HOLOCAUST by Evgeny Finkel A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Political Science) at the UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN–MADISON 2012 Date of final oral examination: 07/12/12 The dissertation is approved by the following members of the Final Oral Committee: Yoshiko M. Herrera, Associate Professor, Political Science Scott G. Gehlbach, Professor, Political Science Andrew Kydd, Associate Professor, Political Science Nadav G. Shelef, Assistant Professor, Political Science Scott Straus, Professor, International Studies © Copyright by Evgeny Finkel 2012 All Rights Reserved i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation could not have been written without the encouragement, support and help of many people to whom I am grateful and feel intellectually, personally, and emotionally indebted. Throughout the whole period of my graduate studies Yoshiko Herrera has been the advisor most comparativists can only dream of. Her endless enthusiasm for this project, razor- sharp comments, constant encouragement to think broadly, theoretically, and not to fear uncharted grounds were exactly what I needed. Nadav Shelef has been extremely generous with his time, support, advice, and encouragement since my first day in graduate school. I always knew that a couple of hours after I sent him a chapter, there would be a detailed, careful, thoughtful, constructive, and critical (when needed) reaction to it waiting in my inbox. This awareness has made the process of writing a dissertation much less frustrating then it could have been. In the future, if I am able to do for my students even a half of what Nadav has done for me, I will consider myself an excellent teacher and mentor. -

1984 Holocaust Conference at Yale Education And

1984 HOLOCAUST CONFERENCE AT YALE EDUCATION AND THE HOLOCAUST: NEW RESPONSIBILITIES AND COOPERATIVE VENTURES Sponsored by the Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies at Yale and Facing History and Ourselves October 28 - 29, 1984 Whitney Humanities Center 53 Wall Street New Haven, Connecticut PROGRAM SUNDAY, OCTOBER 28,1984 Registration Display of Materials of Participants (Auditorium) Materials for display will be accepted from 10:OOam Conference Introduction (Room 208) Welcoming Remarks by Geoffrey Hartman Introduction of Participants and Organizations by Margot Stern Strom Challenges in the Field of Education Moderated by William Parsons An Urban Perspective - Marcia Littell The Washington Museum - David Altschuler A State University - Alvin Rosenfeld State Mandated Education - Edwin Reynolds Coffee Break Witness Accounts: Problems and Promises Lawrence Langer Discussion moderated by Lawrence Langer and Geoffrey Hartrnan Cocktails and Dinner Focus Abroad - Special Public Event CANADA ALAN BARDIKOFF FRANCE MICHAEL POLLAK HOLLAND RABBI AWRAHAM SOETENDORP ISRAEL YEHUDA BAUER WEST GERMANY JACOV KATWAN Auditorium - Open to the Public MONDAY, OCTOBER 29, 1984 8:30am - 9:OOam Coffee 9:OOam - 9:30am Connections: An Open Discussion (Room 208) 9:30am - 10:OOam Trying to Get Things Together: The Case of New Haven - Dorothy and Jerome Singer 10:OOam - 11:Wam Archival ~at&ial:Coordinating Access and Retrieval A Researcher's Perspective - Joan Ringelheim An Archivist's Perspective - Sandra Rosenstock Toward a Shared Communication System- Katharine -

Gino Bartali

There is a wealth of material available covering the many different aspects of the Holocaust, genocide and discrimination. Listed here are a few of the books – including fact, fiction, drama and poetry – that we think are helpful for those interested in finding out more about the issues raised by Holocaust Memorial Day. The majority of these books are available on commonly used bookselling websites – books which are not have contact details for where you can purchase them. The Holocaust & Nazi Persecution A House Next Door to Trauma: Learning from Holocaust Survivors How to Respond to Atrocity – Judith Hassan A Social History of the Third Reich – Richard Grunberger Address Unknown – Kressman Taylor After Daybreak: The Liberation of Belsen 1945 – Ben Shephard After Such Knowledge – Eva Hoffman After the Holocaust: Jewish Survivors in Germany after 1945 – Eva Kolinsky Aimee & Jaguar – Erica Fischer Auschwitz: A History – Sybille Steinbacher Austerlitz – W.G. Sebald British Jewry and the Holocaust – Richard Bolchover By Trust Betrayed: Patients, Physicians and the License to kill in the Children with a Star: Jewish Youth in Nazi Europe – Deborah Dwork Confronting the ‘Good Death’: Nazi Euthanasia on Trial, 1945 – 1953’ – Michael S. Bryan Deaf People in Hitler’s Europe – Donna F. Ryan Disturbance of the Inner Ear – Joyce Hackett Forgotten Crimes: The Holocaust and People with Disabilities – Suzanne Evans www.hmd.org.uk The Holocaust & Nazi Persecution (cont.) From Prejudice to Genocide: Learning about the Holocaust – Carrie Supple Fugitive -

How Much Do You Know About the Holocaust and Jewish Resistance?

TO BEGIN... HOW MUCH DO YOU KNOW ABOUT THE HOLOCAUST AND JEWISH RESISTANCE? Answer each of these questions with TO LEARN MORE... “true” or “false”: ________1. Adolf Hitler took advantage of the dire WEBSITES economic conditions in Germany in his ascent • Defiance, www.defiancemovie.com to power. • Anti-Defamation League, www.adl.org • Jewish Partisans Educational Foundation, ________2. The Nuremberg Laws were an outcome of the www.jewishpartisans.org Nuremberg War Crime Trials. • Museum of Jewish Heritage, www.mjhnyc.org • Simon Wiesenthal Center, www.wiesenthal.com ________3. The Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact was also known • The Jewish Foundation for the Righteous, www.jfr.org as the German-Soviet Non-aggression Pact. • The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, www.ushmm.org ________4. Russian partisans and Jewish partisans fought against the Nazis during World War II. BOOKS ________5. Jewish resistance during the Holocaust • Defiance: The Bielski Partisans, by Nechama Tec. Oxford consisted of guerilla fighters who continually University Press, 1993. engaged the German troops in combat. • Daring to Resist: Jewish Defiance During the Holocaust by Yitzhak Mais (ed). Museum of Jewish Heritage, April 2007. ________6. There were about 5,000 Jewish partisans— • Jewish Resistance in Nazi-Occupied Eastern Europe, by Jews who formed organized, armed resistance Reuben Ainsztein. Harper & Row, 1974. groups and who fought back against the Nazis. • On Both Sides of the Wall, by Vladkka Meed. Schocken Books, June 1993. ________7. Spiritual resistance during World War II was • Resisting the Holocaust, by Ruby Rohrlich (ed.). limited to prayer. Berg, 1998. FILMS ________8. Jewish partisans in or near the Soviet Union relied heavily on the support of Russian • Defiance (2008) partisan groups in their efforts to undermine • Daring to Resist: Three Women Face the Holocaust (1986) the Nazis. -

German Economic Policy and Forced Labor of Jews in the General Government, 1939–1943 Witold Wojciech Me¸Dykowski

Macht Arbeit Frei? German Economic Policy and Forced Labor of Jews in the General Government, 1939–1943 Witold Wojciech Me¸dykowski Boston 2018 Jews of Poland Series Editor ANTONY POLONSKY (Brandeis University) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data: the bibliographic record for this title is available from the Library of Congress. © Academic Studies Press, 2018 ISBN 978-1-61811-596-6 (hardcover) ISBN 978-1-61811-597-3 (electronic) Book design by Kryon Publishing Services (P) Ltd. www.kryonpublishing.com Academic Studies Press 28 Montfern Avenue Brighton, MA 02135, USA P: (617)782-6290 F: (857)241-3149 [email protected] www.academicstudiespress.com This publication is supported by An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access for the public good. The Open Access ISBN for this book is 978-1-61811-907-0. More information about the initiative and links to the Open Access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org. To Luba, with special thanks and gratitude Table of Contents Acknowledgements v Introduction vii Part One Chapter 1: The War against Poland and the Beginning of German Economic Policy in the Ocсupied Territory 1 Chapter 2: Forced Labor from the Period of Military Government until the Beginning of Ghettoization 18 Chapter 3: Forced Labor in the Ghettos and Labor Detachments 74 Chapter 4: Forced Labor in the Labor Camps 134 Part Two Chapter