STATE and REGION GOVERNMENTS in MYANMAR New Edition October 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Identity Crisis: Ethnicity and Conflict in Myanmar

Identity Crisis: Ethnicity and Conflict in Myanmar Asia Report N°312 | 28 August 2020 Headquarters International Crisis Group Avenue Louise 235 • 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 • Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Preventing War. Shaping Peace. Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. A Legacy of Division ......................................................................................................... 4 A. Who Lives in Myanmar? ............................................................................................ 4 B. Those Who Belong and Those Who Don’t ................................................................. 5 C. Contemporary Ramifications..................................................................................... 7 III. Liberalisation and Ethno-nationalism ............................................................................. 9 IV. The Militarisation of Ethnicity ......................................................................................... 13 A. The Rise and Fall of the Kaungkha Militia ................................................................ 14 B. The Shanni: A New Ethnic Armed Group ................................................................. 18 C. An Uncertain Fate for Upland People in Rakhine -

USAID/BURMA MONTHLY ATMOSPHERIC REPORT: May 2019

USAID/BURMA MONTHLY ATMOSPHERIC REPORT: May 2019 Contract Number: 72048218C00004 Myanmar Analytical Activity Acknowledgement This report has been written by Kimetrica LLC (www.kimetrica.com) and Mekong Economics (www.mekongeconomics.com) as part of the Myanmar Analytical Activity, and is therefore the exclusive property of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). Melissa Earl (Kimetrica) is the author of this report and reachable at [email protected] or at Kimetrica LLC, 80 Garden Center, Suite A-368, Broomfield, CO 80020. The author’s views in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. 1 MAY 2019 AT A GLANCE The Tatmadaw extended its unilateral ceasefire in northern and northeastern Myanmar to June 30. The announcement came just after the Tatmadaw met with Northern Alliance members. Most analysts believe the Tatmadaw extended the ceasefire to concentrate on fighting the Arakan Army in Rakhine State. (Page 1) Fighting between the Arakan Army and the Tatmadaw moved further south to Ann Township in Rakhine State. While investment in the state is concentrated in southern Rakhine, fighting in central Rakhine is worrisome for the Government’s plans for development in the state. (Pages 2-4) The Shan State Progress Party (SSPP) and the Restoration Council of Shan State agreed to stop fighting and pursue a peace agreement. (Pages 4-5) The USDP submitted four additional proposals to amend the constitution. The proposed amendments focus on decentralization and will likely be sent to the Constitutional Amendment Committee for review. (Pages 7-8) Three agreements were signed by the Myanmar and Chinese governments following Aung San Suu Kyi’s attendance of the Belt and Road Initiative Forum in Beijing last month. -

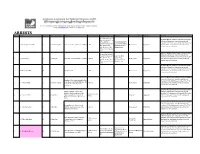

Total Detention, Charge and Fatality Lists

ARRESTS No. Name Sex /Age Father's Name Position Date of Arrest Section of Law Plaintiff Current Condition Address Remark S: 8 of the Export and Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD Import Law and S: 25 leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and of the Natural Superintendent Kyi President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s Disaster Management Lin of Special Branch, 1 (Daw) Aung San Suu Kyi F General Aung San State Counsellor (Chairman of NLD) 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Naypyitaw chief ministers and ministers in the states and law, Penal Code - Dekkhina District regions were also detained. 505(B), S: 67 of the Administrator Telecommunications Law Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD S: 25 of the Natural leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Disaster Management Superintendent President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s law, Penal Code - Myint Naing, 2 (U) Win Myint M U Tun Kyin President (Vice Chairman-1 of NLD) 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Naypyitaw chief ministers and ministers in the states and 505(B), S: 67 of the Dekkhina District regions were also detained. Telecommunications Administrator Law Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s 3 (U) Henry Van Thio M Vice President 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Naypyitaw chief ministers and ministers in the states and regions were also detained. Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Speaker of the Union Assembly, the President U Win Myint were detained. -

B COUNCIL REGULATION (EC) No 194/2008 of 25

2008R0194 — EN — 23.12.2009 — 004.001 — 1 This document is meant purely as a documentation tool and the institutions do not assume any liability for its contents ►B COUNCIL REGULATION (EC) No 194/2008 of 25 February 2008 renewing and strengthening the restrictive measures in respect of Burma/Myanmar and repealing Regulation (EC) No 817/2006 (OJ L 66, 10.3.2008, p. 1) Amended by: Official Journal No page date ►M1 Commission Regulation (EC) No 385/2008 of 29 April 2008 L 116 5 30.4.2008 ►M2 Commission Regulation (EC) No 353/2009 of 28 April 2009 L 108 20 29.4.2009 ►M3 Commission Regulation (EC) No 747/2009 of 14 August 2009 L 212 10 15.8.2009 ►M4 Commission Regulation (EU) No 1267/2009 of 18 December 2009 L 339 24 22.12.2009 Corrected by: ►C1 Corrigendum, OJ L 198, 26.7.2008, p. 74 (385/2008) 2008R0194 — EN — 23.12.2009 — 004.001 — 2 ▼B COUNCIL REGULATION (EC) No 194/2008 of 25 February 2008 renewing and strengthening the restrictive measures in respect of Burma/Myanmar and repealing Regulation (EC) No 817/2006 THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION, Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Community, and in particular Articles 60 and 301 thereof, Having regard to Common Position 2007/750/CFSP of 19 November 2007 amending Common Position 2006/318/CFSP renewing restrictive measures against Burma/Myanmar (1), Having regard to the proposal from the Commission, Whereas: (1) On 28 October 1996, the Council, concerned at the absence of progress towards democratisation and at the continuing violation of human rights in Burma/Myanmar, imposed certain restrictive measures against Burma/Myanmar by Common Position 1996/635/CFSP (2). -

Election Monitor No.49

Euro-Burma Office 10 November 22 November 2010 Election Monitor ELECTION MONITOR NO. 49 DIPLOMATS OF FOREIGN MISSIONS OBSERVE VOTING PROCESS IN VARIOUS STATES AND REGIONS Representatives of foreign embassies and UN agencies based in Myanmar, members of the Myanmar Foreign Correspondents Club and local journalists observed the polling stations and studied the casting of votes at a number of polling stations on the day of the elections. According the state-run media, the diplomats and guests were organized into small groups and conducted to the various regions and states to witness the elections. The following are the number of polling stations and number of eligible voters for the various regions and states:1 1. Kachin State - 866 polling stations for 824,968 eligible voters. 2. Magway Region- 4436 polling stations in 1705 wards and villages with 2,695,546 eligible voters 3. Chin State - 510 polling stations with 66827 eligible voters 4. Sagaing Region - 3,307 polling stations with 3,114,222 eligible voters in 125 constituencies 5. Bago Region - 1251 polling stations and 1057656 voters 6. Shan State (North ) - 1268 polling stations in five districts, 19 townships and 839 wards/ villages and there were 1,060,807 eligible voters. 7. Shan State(East) - 506 polling stations and 331,448 eligible voters 8. Shan State (South)- 908,030 eligible voters cast votes at 975 polling stations 9. Mandalay Region - 653 polling stations where more than 85,500 eligible voters 10. Rakhine State - 2824 polling stations and over 1769000 eligible voters in 17 townships in Rakhine State, 1267 polling stations and over 863000 eligible voters in Sittway District and 139 polling stations and over 146000 eligible voters in Sittway Township. -

Members of Parliament-Elect, Myanmar/Burma

To: Hon. Mr. Ban Ki-moon Secretary-General United Nations From: Members of Parliament-Elect, Myanmar/Burma CC: Mr. B. Lynn Pascoe, Under-Secretary-General, United Nations Mr. Ibrahim Gambari, Under-Secretary-General and Special Adviser to the Secretary- General on Myanmar/Burma Permanent Representatives to the United Nations of the five Permanent Members (China, Russia, France, United Kingdom and the United states) of the UN Security Council U Aung Shwe, Chairman, National League for Democracy Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, General Secretary, National League for Democracy U Aye Thar Aung, Secretary, Committee Representing the Peoples' Parliament (CRPP) Veteran Politicians The 88 Generation Students Date: 1 August 2007 Re: National Reconciliation and Democratization in Myanmar/Burma Dear Excellency, We note that you have issued a statement on 18 July 2007, in which you urged the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) (the ruling military government of Myanmar/Burma) to "seize this opportunity to ensure that this and subsequent steps in Myanmar's political roadmap are as inclusive, participatory and transparent as possible, with a view to allowing all the relevant parties to Myanmar's national reconciliation process to fully contribute to defining their country's future."1 We thank you for your strong and personal involvement in Myanmar/Burma and we expect that your good offices mandate to facilitating national reconciliation in Myanmar/Burma would be successful. We, Members of Parliament elected by the people of Myanmar/Burma in the 1990 general elections, also would like to assure you that we will fully cooperate with your good offices and the United Nations in our effort to solve problems in Myanmar/Burma peacefully through a meaningful, inclusive and transparent dialogue. -

Situation Analysis of Myanmar's Region and State Hluttaws

1 Authors This research product would not have been possible without Carl DeFaria the great interest and cooperation of Hluttaw and government representatives in Mon, Mandalay, Shan and Tanintharyi Philipp Annawitt Region and States. We would like express our heartfelt thanks to Daw Tin Ei, Speaker of the Mon State Hluttaw, U Aung Kyaw Research Team Leader Oo, Speaker of the Mandalay Region Hluttaw, U Sai Lone Seng, Aung Myo Min Speaker of the Shan State Hluttaw, and U Khin Maung Aye, Speaker of the Tanintharyi Region Hluttaw, who participated enthusiastically in this project and made themselves, their Researcher and Technical Advisor MPs and staff available for interviews, and who showed great Janelle San ownership throughout the many months of review and consultation on the findings and resulting recommendations. We also wish to thank Chief Ministers U Zaw Myint Maung, Technical Advisor Dr Aye Zan, U Linn Htut, and Dr. Le Le Maw for making Warren Cahill themselves and/or their ministers and cabinet members available for interviews, and their Secretaries of Government who facilitated travel authorizations and set up interviews Assistant Researcher with township officials. T Nang Seng Pang In particular, we would like to thank the eight constituency Research Team Members MPs interviewed for this research who took several days out of their busy schedule to organize and accompany our research Hlaing Yu Aung team on visits to often remote parts of their constituencies Min Lawe and organized the wonderful meetings with ward and village tract administrators, household heads and community Interpreters members that proved so insightful for this research and made our picture of the MP’s role in Region and State governance Dr. -

2 December 2020 1 2 Dec 20 Gnlm

FIRM COMMITMENT KEY TO REDUCING RISK OF HUMAN TRAFFICKING DURING POST COVID-19 PERIOD PAGE-8 (OPINION) NATIONAL NATIONAL Myanmar to join new Senior Officials Figures and percentages of 2020 Multiparty Democracy Counterterrorism Policy Forum General Election to be published in newspapers PAGE-6 PAGE-10 Vol. VII, No. 230, 3rd Waning of Tazaungmon 1382 ME www.gnlm.com.mm, www.globalnewlightofmyanmar.com Wednesday, 2 December 2020 University of Yangon holds 100th anniversary celebrations State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, Vice-President U Myint Swe, Amyotha Hluttaw Speaker Mahn Win Khaing Than, Union Ministers, Yangon Region Chief Minister and YU Rector are virtually cutting the ceremonial ribbon for 100th anniversary of Yangon University. PHOTO : MNA HE 100th anniversary Dr Phoe Kaung used a virtual congratulatory remark on the Kyi (now the State Counsellor) gence in appointment, transfer of University of Yangon system in cutting the ceremonial ceremony. for ‘Drawing University New Act and promotion of academic staff was held on virtual cel- ribbon of the opening ceremony. (Congratulatory speech of and Upgrade of Yangon Univer- and other issues in relation to the Tebrations yesterday. State Counsellor Daw Aung Amyotha Hluttaw Speaker is sity (Main)’ ; she led the commit- academic sector, administrative After the opening ceremony San Suu Kyi, in her capacity as covered on page 5 ) tee that worked for upgrade and sector and infrastructural devel- of the event with the song enti- the Chairperson of Steering Union Minister for Educa- renovation of the university in opment of the university by draw- tled ‘Centenary Celebrations of Committee on Organizing Cen- tion, the secretary of the steer- line with international standards. -

Restrictive Measures – Burma/Myanmar) (Jersey) Order 2008 Arrangement

Community Provisions (Restrictive Measures – Burma/Myanmar) (Jersey) Order 2008 Arrangement COMMUNITY PROVISIONS (RESTRICTIVE MEASURES – BURMA/MYANMAR) (JERSEY) ORDER 2008 Arrangement Article 1 Interpretation ................................................................................................... 3 2 Prohibitions on importation, etc., of goods originating in or exported from Burma/Myanmar .................................................................................... 4 3 Exceptions to prohibitions in Article 2 ........................................................... 5 4 Prohibition on exportation, etc., to Burma/Myanmar of goods which might be used for internal repression .............................................................. 5 5 Prohibition on exportation, etc., to Burma/Myanmar of goods for use in certain industries ......................................................................................... 5 6 Exception to Article 5 ..................................................................................... 6 7 Prohibition on provision of technical or financial assistance to persons in Burma/Myanmar ......................................................................................... 7 8 Prohibition on provision of technical assistance to enterprises in Burma/Myanmar engaged in certain industries .............................................. 7 9 Derogation for certain authorizations ............................................................. 8 10 Authorizations not to be retrospective ........................................................... -

Recent Arrests List

ƒ ARRESTS No. Name Sex Position Date of Arrest Section of Law Plaintiff Current Condition Address Remark Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD S: 8 of the Export and Superintendent Kyi 1 (Daw) Aung San Suu Kyi F State Counsellor (Chairman of NLD) 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Import Law Lin of Special Branch President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s S: 25 of the Natural Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD Superintendent Myint 2 (U) Win Myint M President (Vice Chairman-1 of NLD) 1-Feb-21 Disaster Management House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Naing law President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD 3 (U) Henry Van Thio M Vice President 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s Speaker of the Amyotha Hluttaw, the Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD 4 (U) Mann Win Khaing Than M upper house of the Myanmar 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and parliament President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s Speaker of the Union Assembly, the Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD 5 (U) T Khun Myat M Joint House and Pyithu Hluttaw, the 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and lower house of the Myanmar President U Win Myint were detained. -

USAID/BURMA MONTHLY ATMOSPHERIC REPORT January 2020

USAID/BURMA MONTHLY ATMOSPHERIC REPORT January 2020 Contract Number: 72048218C00004 Myanmar Analytical Activity Acknowledgement This report has been written by Kimetrica LLC (www.kimetrica.com) and Mekong Economics (www.mekongeconomics.com) as part of the Myanmar Analytical Activity, and is therefore the exclusive property of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). Melissa Earl (Kimetrica) is the author of this report and reachable at [email protected] or at Kimetrica LLC, 80 Garden Center, Suite A-368, Broomfield, CO 80020. The author’s views in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. USAID.GOV DECEMBER 2019 MONTHLY ATMOSPHERIC REPORT | 1 JANUARY 2020 AT A GLANCE Myanmar’s ICOE Finds Insufficient Evidence of Genocide. The ICOE admits there is evidence that Tatmadaw soldiers committed individual war crimes, but rules there is no evidence of a systematic effort to destroy the Rohingya people. (Page 1) The ICJ Rules Myanmar Must Take Measures to Protect the Rohingya From Acts of Genocide. International observers laud the ruling as a major step toward fighting genocide globally, but reactions to the ruling in Myanmar are mixed. (Page 2) Fortify Rights Documents Five Cases of Rohingya IDPs Forced to Accept NVCs. The international community and the Rohingya condemned the cards, saying they are a means to keep the Rohingya from obtaining full citizenship rights by identifying them as “Bengali,” not Rohingya. (Page 3) During the Chinese President’s State Visit to Myanmar, the Two Countries Signed Multiple MoUs. The 33 MoUs that President Xi Jinping cosigned are related to infrastructure, trade, media, and urban development. -

“Pre-Election Monitoring Study in Rakhine State”

“Pre-Election Monitoring Study in Rakhine State” Table of Contents KEY FINDINGS ............................................................................................................................................... 2 1. BACKGROUND AND INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................ 5 1.1. POLITICAL PARTY LANDSCAPE IN RAKHINE STATE............................................................................ 7 1.2. INTERNATIONAL STANDARDS ON FREE AND FAIR ELECTIONS .............................................................. 8 1.3. ELECTORAL SYSTEM IN MYANMAR ................................................................................................. 10 2. OBJECTIVE AND SCOPE OF THE STUDY ..................................................................................... 11 1. METHODOLOGY ................................................................................................................................ 11 1.1. SAMPLING ...................................................................................................................................... 11 1.2. RESEARCH PROCESS ........................................................................................................................ 12 1.3. LIMITATION OF STUDY .................................................................................................................... 12 2. FINDINGS ............................................................................................................................................